|

Nigel

Irens is a leading yacht

designer. He is perhaps best known as designer of the Cable and wireless Adventurer,

a 35m trimaran

motor yacht which completed a record-breaking circumnavigation in 1998,

and of the record-breaking trimaran used by Ellen

MacArthur to break the world record for solo circumnavigation

in 2005, of which see more below.

His

design portfolio is wide-ranging, from record-breaking yachts to

innovative cruising designs such as Roxane, syntheses of

traditional design such as the Westernman cutters – designed in

association with Ed Burnett – or the launch Rangeboat, a 12m

meter power craft of traditional appearance. Irens is perhaps

particularly noteworthy for the simplicity,

the efficiency, the essential elegance of his designs, something that we

also value.

Nigel

Irens has been involved in many exciting boat projects, including ENZA

and the CABLE

& WIRELESS ADVENTURER. See the short history below for other

boats.

We

feel that there is nonetheless a common link between them in that they are

all boats designed for very specific purposes for owners who are very

exacting in their requirements.

Nigel

is quoted as saying: "There is no shortage of mainstream production

boats available in the world but if you are looking for something original

and different then he would like to hear from you".

Nigel Irens has been a pioneer in the field of racing multihull design since 1979 having been responsible for many successful boats such as ‘FUJI’ (3 times winner of the UK’s Single-Handed Transatlantic), FLEURY MICHON (winner of the French ‘ROUTE du RHUM’) and

B&Q-CASTORAMA in which Dame Ellen MacArthur beat the single-handed Round the World Record in 2005. That record is currently

and was subsequently taken (and held) by Frenchman

Francis Joyon, again in an Irens designed trimaran.

In

1994 Peter

Blake, Robin Knox-Johnston took the trophy from Bruno Peyron in

the catamaran: Enza New Zealand (28m)

- 74:22:17:22.

This yacht was to have a varied career on the racing circuit, finally

being converted to solar and hydrogen

power, with electric drives, and renamed Energy

Observer.

Irens has also been responsible for the design of successful powerboats such as the 43 metre trimaran OCEAN EAGLE class. Commissioned by the French shipyard CMN as a highly efficient Offshore Patrol Vessel – three of which have so far been built. Irens has also maintained a strong interest in cruising boats – again both power and sail driven. The 19 metre (63ft) wooden schooner MAGGIE B, completed a 38,000 mile

circumnavigation over a two year period.

The Irens office is also heavily committed to the development of semi-displacement motor vessels that offer a more pleasurable and ecologically satisfying alternative for cruising under power than their ubiquitous

planing-hulled counter-parts.

PROFESSIONAL BOATBUILDER 30 NOVEMBER 2022 - SLIPPERY NIGEL IRENS LAUNCH

Clara, a modest and deceptively simple launch, is the latest powerboat project from U.K. yacht designer Nigel Irens, and a timely reminder that boating can be simple, efficient, affordable, and ultimately pleasurable. In a year defined by supply-chain disruptions, fuel scarcity, and broad economic uncertainly, the 26‘3“ (8m) open boat with a scant 6‘6“ (1.98m) beam and 1,825-lb (827.8-kg) displacement offers a uniquely refined model intended to be built of CNC-cut plywood and epoxy in a modest shop and powered by a 20-hp outboard or equivalent

electric

motor.

Regular readers of the magazine will recognize this as the latest iteration in Irens’s refinement of low-displacement/length (LDL) hullforms that defy the accepted wisdom that 1.34 times the square root of the waterline length in feet defines the hull speed of a displacement vessel. (For details on Irens’s earlier LDL designs, see “Slippery When Wet,” Professional BoatBuilder No. 187, page 68.) Indeed, Irens reported that the new boat reached 12 knots in sea trials, nearly twice her theoretical hull speed. No surprise, as Clara’s hullform pushes the LDL form to new extremes, with the forefoot a little deeper and the beam a little narrower than Irens’s previous models. The plumb bow and very fine entry yield a hull that resembles a wood-splitting maul. It’s an evolution of the early design process Irens described to me over the phone during

COVID isolation two years ago: Take a cardboard toilet-paper tube and pinch the ends together perpendicular to one another. The result is his basic LDL hullform. He explained further that sharpness is essential to his design’s efficiency, from the wave-cleaving stem to the crisp transom trailing edge, which separates cleanly from the water that wants to cling to the hull’s running surface at speed.

There’s more to Clara than exceeding performance predictions. For years Irens has been thinking about efficient construction methods for his lightweight wood-epoxy powerboats that would ensure consistency of hull shape, structural integrity, and performance and be accessible to a global market. By optimizing CAD design files for computer-controlled cutting

technology - waterjets and multiaxis routers - he says he’s confident that the shapes and quality of essential fit will be uniform and not depend entirely on the builder’s hand skills and experience. At a time when recruiting and retaining a skilled workforce have become major challenges for boatbuilders, the ability to cut accurate curves, bevels, lapped joints, and faying surfaces with a CNC router is a huge advantage.

The results should be fairly uniform wherever the boat is built. Ideally, the refined CAD files will make it possible to cut an identical kit of parts anywhere in the world from locally available marine

plywood, and for a local builder with a modest shop to put it together with a minimum of fuss

- just like she goes through the water.

Details of Irens’s design process and of the builds are documented at the Clara Boat website.

Clara Boat Co Ltd, 10 Market Close, Ashburton, Devon TQ13 7FN, U.K.

MAKEOVER

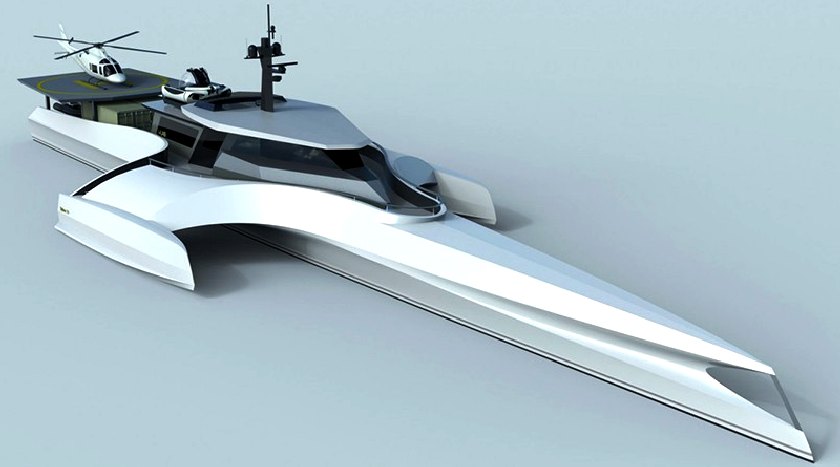

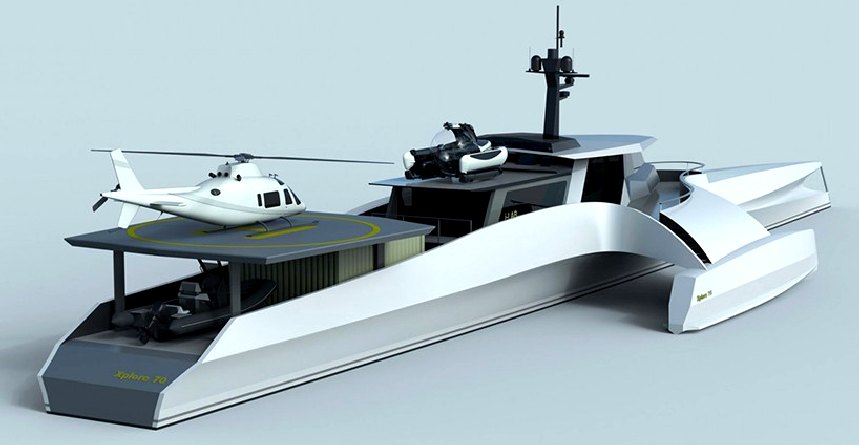

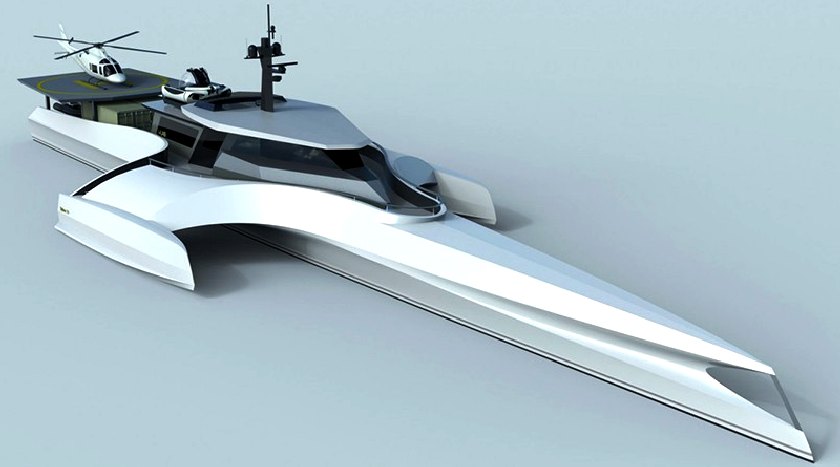

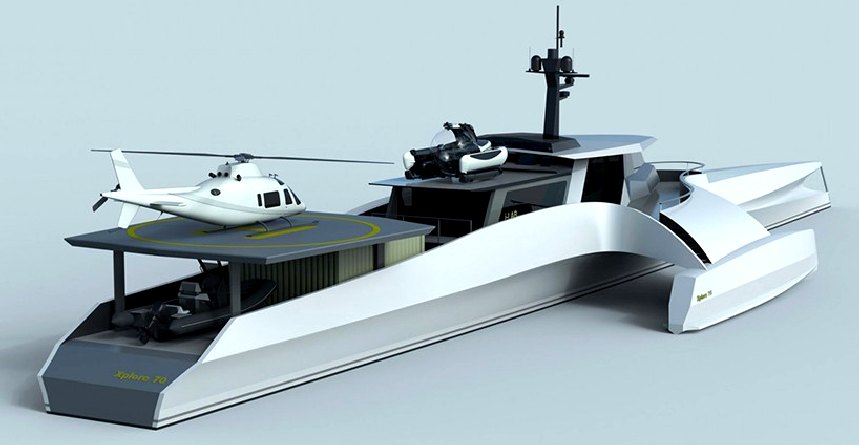

- A dramatic contemporary style of explorer yachts has been created by Nigel

Irens design and CMN shipyard, joined by French designer and fellow long term collaborator

Christophe Ghedal-Anglay. The group came together to work on the development of a pair of trimaran expedition yachts, designated the ‘origin 575’ and ‘xplore 70’.

The partnership emphasizes comfort, speed and ocean crossing capability, with a trimaran configuration that is significantly more efficient than a conventional monohull. ‘Having applied what we had learned through the development of offshore racing trimarans to their motor-driven equivalents some 25 years ago, it’s exciting to see how successfully that technology has now been passed on to the three ocean eagle 43 patrol vessels produced by

CMN,’ comments designer

Nigel Irens. ‘I have had the pleasure of traveling many thousands of miles in powered trimarans and am passionate about sharing that experience with owners who want to be part of this exciting development.’

ENERGY OBSERVER 7 NOVEMBER 2018 - IT'S A PLEASURE TO SEE THE NEW LIFE

OF THE BOAT

Francis Joyon, Ellen MacArthur and before them, Mike Birch, winner of the first Route du Rhum and Sir Peter Black, Enza, have put their trust in Nigel Irens to design their record-chasing engines. Energy Observer came off the naval architect’s drawing board in 1983 under the name of Formule TAG. Lengthened and transformed into an experimental vessel, the 30-meter catamaran today explores the planet. Meeting with its architect. QUESTIONS & ANSWERS

Q. In 1982, when Mike Birch contacted you to design his new vessel, what were his specifications?

A. It was a time when catamarans dominated, with Loïc Caradec’s Royale II, Marc Pajot’s Elf Aquitaine or Charente Maritime skippered by a group of friends led by Jean-François Fountaine. Formule TAG (editor’s note: the original name of Energy Observer) had to be, with its 80 feet (24.37 meters), the largest catamaran of its time.

Q. What was the vessel’s program?

A. Mainly crewed races but also record attempts.

Q. You designed it, the work was coordinated with the architectural firm Huot and Dupuis, but where was it built?

A. It was built in Montreal (Canada) by the aviation company Canadair, the property of TAG the sponsor. The most notable change was the size. Nobody had ever made such a big vessel.

Q. Has the catamaran therefore benefited from the technology of the aviation industry?

A. This was a real opportunity. It’s the first racing vessel to have benefited from aviation standards with Kevlar material (pre-preg of resin (prepeg). At the time, it was the world’s second largest composite object… just after the doors of the

space

shuttle!

Q. Why choose Kevlar?

A. Kevlar was available in larger quantities than carbon in the 1980s. It then became outdated because it had very good mechanical qualities in traction but a lot less in compression since its adhesion between resin and fibers is not very good. All the planks were made of

Kevlar. Carbon was used for the deck edge (editor’s note: deck and hull junction line). The same for the arm parts where there was a lot of compression. The challenge was to adapt this standard aerospace technology, which used autoclaves, to our requirements where we were unable to use autoclaves due to the size of our parts. We did a lot of testing with the help of Canadair personnel.

Q. Were there any anecdotes during construction?

A. Assembling was done in a shed in Quebec in a public area that was open to the public, as part of the 400th anniversary celebrations of Malouin Jacques Cartier’s discovery of Canada. It was sometimes a bit surreal when we were working at night to the sound of an orchestra. We also learned six weeks before its inauguration that the vessel was going to sail on the day of its launch with Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Canadian Prime Minister, on board. It was tight in terms of organization. We strengthened the teams and worked day and night. On launch day, a turnbuckle (editor’s note: a device which holds the cables) was defective. We have anyhow sailed under reduced sails with “do-it-yourself” workmanship!

Q. The fact that the vessel has today a new life, is this important for you?

A. It’s very important! After 35 years and the different lives that this vessel has had, it’s great to see it continuing. Especially in this context of choosing to

recycle a vessel rather than building a new one is a good example.

Q. What are your thoughts on the vessel’s transformation and changes?

A. The load on the structure in this new configuration (editor’s note: the pod in which the crew lives) doesn’t pose any structural problem to the hulls. It doesn’t risk anything compared to what happens to a vessel whose hulls are loaded by sail plan efforts. The loads are minimal compared to what it has endured during its different world tours. The vessel is in refuge! A great refuge for a great project. I’m very impressed with the quality of the transformation.

Performance is impressive with a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h) and a range of between 7,408 and 9,260 kilometers at 18 knots (34 km/h). the interior arrangement of the ‘origin 575’ (57.5 meter design) can be customized to suit an owner’s requirements, but each can accommodating 10 guests and eight crew. there is deck space for a mini-submarine and a 4.5 meter tender while the stern garage offers storage for a six meter tender and personal watercraft. The yacht features a helicopter deck, as well as space for larger tenders and a mini sub. the extra deck space is able to board containerized units ideal for rapid role enhancement whether it’s a research laboratory, aquarium or a dive-centre. this unique capacity to cross oceans at speed and in comfort combines the pleasure of the voyage itself with the excitement of arriving at new destinations in such a way that they blend into a single seamless experience.

SAIL MAGAZINE 2 AUGUST 2017 (ORIGINAL JUNE 5 2014) - NIGEL IRENS DESIGNS SOME OF THE FASTEST RACING MULTIHULLS

Tucked away down a narrow alley in the picturesque town of Ashburton, on the edge of Dartmoor National Park in England, is a tiny building called the Tenter loft, a relic from the ancient wool industry when cloth was stretched on tenterhooks. It’s now the quirky office of British multihull designer

Nigel Irens, the man behind some of the fastest sailing boats on the planet.

Tucked away down a narrow alley in the picturesque town of Ashburton, on the edge of Dartmoor National Park in England, is a tiny building called the Tenter loft, a relic from the ancient wool industry when cloth was stretched on tenterhooks. It’s now the quirky office of British multihull designer Nigel Irens, the man behind some of the fastest sailing boats on the planet.

“The only things stretched in here are catamarans and trimarans,” says one of his team in a play on Irens’s maxim on multihull design that can be paraphrased as “design the longest boat you can possibly accept and then add a few feet.”

For 40 years, Irens has been at the cutting edge of multihull ocean racing. His name is on a string of record-setting catamarans and trimarans that are bywords among multihull aficionados everywhere, including ENZA, the 92-foot cat on which Peter Blake and Robin Knox-Johnston set the first Jules Verne sailing record in 1994; iDEC, on which Francis Joyon became the fastest man to circumnavigate solo; B&Q Castorama, on which Ellen Macarthur became not just the fastest woman around the world but, for a while, the fastest person, period. These and many other designs have long been celebrated as a kind of fusion of art and science. Irens’s designs, built for speed and endurance, have been called poems of flowing function, and for decades have been sought after by the hottest sailors on the race circuits.

At 67, Irens is as busy as ever. He jokes about “reaching the sun-filled plateaus” of retirement, but quickly adds, “I’ve always got an ambition for the next project.” And the projects keep flowing, just like the River Ashburn, which burbles, literally, underneath his office. We might be 20 miles from the sea, but the rush of water for Irens is a 24-hour soundtrack.

“I’ve been fascinated by water and slippery boats my whole life,” says Irens, who in his student days in the 1960s lived on an old workboat on the

River Hamble while he studied for a diploma in Boatyard Management at

Southampton College of Technology. His liveaboard neighbor was SAIL Magazine writer Tom Cunliffe. Both were impoverished students who lived in fear of the harbormaster’s visit to collect harbor dues. Irens was even Honorary Commodore of the Old Gaffers’ Association in 1970. Who would have guessed that 40 years later he’d design a wooden gaff cutter, Westernman, for Cunliffe, let alone generate a string of maxi multihulls and become a consultant for the America’s Cup?

Irens’s love for sailing (and multihulls) goes back to family holidays on his father’s 30-foot plywood catamaran, in which they crossed the

English Channel to France and cruised St-Malo, La Roche Bernard and the canals.

In the early 1970s Irens was working in a boatyard on the River Severn with multihull pioneer Paul Weychan, building what was claimed to be Europe’s biggest trimaran, the 52-foot Tacitimu, a Polynesian word for “Outrigger of the Gods.” In 1972 Irens and a friend opened a sailing school in Bristol, and by 1977 he had designed his first boat, Promenade, a 60-foot cruising trimaran that’s still chartering today in the

British Virgin

Islands. In 1978 Irens salvaged the wreck of a 31-foot Dick Newick Val Class trimaran, Jan of Santa Cruz, and shipped her from the Canary Islands to the UK to rebuild with legend-to-be Mike Birch. Together with friend Mark Pridie, Irens sailed her to class victory in the 1978 doublehanded Round Britain and Ireland Race. She became the launch pad for his career.

SECRETS OF SPEED

Nigel designed his first racing trimaran, the 40-foot Gordano Goose, in 1980 and built her in a barn in Easton-in-Gordano, near the River Avon outside Bristol. Her highly rockered hulls showed Newick’s influence, but Irens’s first-hand seagoing experience and guidance from a structual engineer gave him the confidence to push the envelope. Gordano was low-slung, with a slim central hull and low windage. The turtleback cabin created a compression beam from end to end to handle the rigging loads. She was a true “next generation” tri and reportedly one of the first to almost sail on one ama.

Famously, Gordano Goose was the tri in which Irens beat Eric Tabarly, Mike Birch and Philippe Poupon in a memorable 24-hour singlehanded race out of St-Malo in 1981. “By the grace of God the weather was squally with changing wind directions, and my boat was smaller and more manageable, though I still had 17 sail changes! When the sun came up on the second day, I had no idea where I was and exhaustion had set in. At the last windward buoy, I saw Philippe Poupon, in a similar sized tri, ahead of me. I thought ‘Wow, second place, amazing!’ Then Poupon hoisted his starcut

spinnaker - and promptly ran over it!” Irens overhauled him to win the £4,000 prize, “a king’s ransom” in those days.

“I had a huge escort to the finish line,” Irens says, smiling at the memory. “It was as if I’d won a round-the-world race.”

He adds - most emphatically - that this was his “first and last attempt at a solo race,” but that didn’t stop him from designing British sailor

Tony

Bullimore’s 40-foot trimaran IT82, in which the two of them won their class in the 1982 Round Britain Race. (Bullimore would go on to chalk up third in class aboard IT82 in the 1984 Observer Singlehanded

Transatlantic Race.)

After that came another trimaran design for Bullimore, the beautifully sculpted 60-footer, Apricot. Part of Nigel’s genius has long been to enlist outside talent and

skills - people like Martyn Smith, then ex-Chief Engineer for British Aerospace, who designed the Concorde’s nose

cone - and the approach is much in evidence in this design. Smith, for example, took over the structural composite work, while the boat’s 78-foot carbon wing mast was designed by Barry Noble, a former sparmaker who was then making carbon-fiber violins and cellos.

The result was music to their ears - a state-of-the-art tri that Bullimore and Irens sailed to outright victory in the 1985 Round Britain Race. They also won their class in every leg of the Round Europe Race that year. Their reward was to be jointly elected Yachtsmen of the Year at the London Boat Show.

“I look back on those racing days with huge pleasure, but I’m not a natural ocean sailor,” says Irens. “I spend my time lurching between fear and boredom. I like to be able to see the land. A French journalist once asked me about this. The French are in love with the romance of the sea, and I think he was a bit shocked. I’m probably regarded as a bit of a Philistine!”

In between IT82 and Apricot, Irens designed what was then the world’s longest racing

catamaran - the 80-foot carbon

fiber/Kevlar Formule Tag, built for Canadian Mike Birch in Montreal. Tag was built by Canadair using aerospace technology. The largest ever pre-preg structures were “cooked” in giant ovens. Irens moved to Montreal to oversee her build. Launched in 1983, she was the first

multihull - and the first racing sailboat - to beat the 500-mile-a-day barrier, clocking 517 miles in 24 hours during the 1984 transatlantic Quebec-Saint-Malo race.

Ten years and thousands of miles later she was stretched to 92 feet, re-named ENZA New Zealand, and circled the world. The extra length boosted her performance by 15 percent. A new accommodation

module - the “god-pod” - was built into the center main beam for co-skippers

Peter Blake and

Robin

Knox-Johnston.

Irens was in Brest, France, when they sailed across the finish line in 1994 after 74 days and 22 hours to win the Jules Verne Trophy. The remarkable old warhorse was later campaigned in round-the-world races by

Tracy Edwards as Royal & Sun Alliance (dismasted) and was stretched to 102 feet by Tony Bullimore and sailed as Team Legato in The Race (2001).

After that she was Daedalus for a while, and then Doha. In 2010, in her last incarnation as Spirit of Antigua, she capsized in the Bay of Biscay.

She now lies forlorn in

Brest, stripped of gear, a ghost from ocean racing history.

Never one to dwell on the past, Irens is now excited by his latest hi-tech catamarans, two custom designs for private clients undergoing sea trials this summer in Britain and Middle East.

SUSTAINABLE

RESOURCE - Timber is a renewable asset and one that should be treated with

respect. We need to plant more trees to prevent deforestation,

soak up carbon

dioxide and generate oxygen.

GOING PRODUCTION

Irens has also been working with Gunboat, designing the new 55 and 60 models. It’s the first time he has been involved with a production builder. With typical modesty, he’s never cashed in on his reputation and admits he could have been much richer if he’d been more commercially minded.

Gunboat’s founder and CEO Peter Johnstone, having redefined the luxury catamaran market, was looking for a fresh approach after 10 years with Morrelli & Melvin Design. He turned to Irens, whose record-breaking multihulls have never suffered major damage. Speed and reliability are indispensable qualities in ocean cruising cats.

“Working with Gunboat is a great opportunity to do a Rolls Royce job on research and development,” Irens says. “You don’t often get the chance to devote so much time to one boat.”

The cruising cat has been left behind, he adds. “Catamarans have always boasted plenty of space, but sailing them from A to B was more about ‘moving house’ than sailing.”

A consultant in 2008 for the Alinghi team, Irens also believes the America’s Cup has opened the door to more people having multihulls. “The glamour surrounding the event has legitimized the catamaran. We are all victims of fashion, and for many people catamarans were not seen as socially acceptable, because they didn’t sail well. The market for charter cats has been very successful, but performance has been dragged down by extra concessions to space and comfort, which add weight. Catamarans were simply not seen as the domain of someone with a big budget. But they will be now.”

For the new Gunboat 55 hull Irens has created a unique monocoque all-carbon structure that requires no forward crossbeam to support the hulls, thus reducing windage and drag. New furniture, cored with Divinycell foam, has reduced weight by half.

Another small innovation Irens has brought to Gunboat is “a simple little chine” on its new 60-footer, a development from Sodebo. Johnstone describes how one Gunboat sailed 2,000 miles and had spray on its deck only twice, once during a 45-knot gale. “Nigel’s chine made all the difference,” he said.

A lot of work has also been done on the design of the pivoting centerboards on the Gunboat 55 and 60, as Johnstone has become a centerboard evangelist after listening to Gunboat owners’ tales of daggerboard problems.

“The new centerboard mechanisms are complex and expensive and have gone through several evolutions,” says Irens, who brought in UK engineer Roger Scammell to help refine them, based on his experience working on the steering systems for Irens’s tri B&Q and the canting keels for a number of Open 60s.

The benefits of a centerboard are ease of adjustment - you can instantly balance the boat by adjusting the trim of the

board(s) - less noise, less drag and improved interior space. The board is controlled by

hydraulic rams and can be set at any depth and angle. It can even go 5 degrees forward of vertical, the normal position being vertical. If you hit something, the shear pin on the rams will break so the board kicks up without damaging the board or the mechanism

Innovative design, use of the latest materials, and the addition of a carbon rig supplied by Swedish company Marstrom Composite has helped increase speed. A rotating wing mast and a new beam arrangement permits tight sheeting angles for an upwind-oriented Code 0.

Johnstone is full of praise for Nigel’s input and notes that every hour spent in design has cut the production hours by a sizeable factor. “We do almost no cutting once the carbon fiber hull is built,” he says.

Irens has dispensed with superfluous cabins that weigh down the typical cruising cat and kill performance. But she still has two superyacht-worthy cabins, plus an owner’s study/workshop. Speed-wise, Johnstone says the 55 (which replaces the 48) will be similar to the 66, which he considers “a bit of a rocket ship.”

At press time, Irens’s radical Middle East “stealth” project, A65 was due to be unveiled at the Dubai Boat Show in March. “We’ve taken an oath of secrecy, but I’m very excited to see how she sails. I’ve never created a boat like this before, and the owner seems pleased with the performance,” he says.

“We’ve had priceless design discussions with six or seven people on conference call on Skype. The owner is a man after my own heart. Most boats are better for being longer with the same accommodation, but few people have the courage of their convictions. ‘Let’s do it!’ the owner said to me. So A65 is essentially a 53-footer on 65-foot hulls with a high-performance rotating wing mast and carbon rigging.

“No catamaran should suffer the excesses of wave-making drag. It’s ridiculous. By stretching her and creating a hull displacement-length ratio that doesn’t attract drag you have far better sea-keeping qualities. You’ve created a wave-piercing bow that acts just like the leeward hull of a

trimaran. It’s the same thing we did with Sodebo, where there’s a chine to deflect spray. You get a much nicer ride with less pitching.”

Like the Gunboats, A65 has a forward cockpit and, unusually, tiller steering, plus two owners’ suites. She is built for long-distance performance cruising.

Also launching this summer is Irens’s other top secret project, APC78—a 78-foot Advanced Performance Cat being built in the UK by Green Marine, a company that’s also done America’s Cup challengers, Open 60s and Volvo Ocean Race boats. Built in carbon and Nomex, she will have composite rigging incorporating the smallest diameter carbon rigging on the market from Future Fibers.

DAYS OF FUTURE PAST

This is all light years away from the Greyhound pub in Bristol, where in 1973, Irens was part of a syndicate eager to compete for a £500 prize in the World Sailing

Speed Record trials at Portland Harbour near Weymouth. “We cleared out the pub after lots of arguing over design and had competitions for one-meter long models on a pond on Sunday mornings. People used to party until two in the morning and then build models until 10. There were 10 of us paying £50 each, plus unofficial sponsorship from the

BBC - most of the materials came from a friend who worked there as a set designer. The result was a proa with five solid wing sails arranged like a vertical Venetian blind with trailing edge flaps.” Christened The Clifton Flasher, she could only sail on one tack. Nigel helmed her over the 500-meter course at a fastest speed of 22.14 knots.

Looking into the future, it’s pretty obvious that although the idea of lifting a sailing boat on to

hydrofoils has been around for several decades, it is only now that real progress is being made in translating theoretical gains into tangible ones. The stunning performances demonstrated by Oracle Team USA and Team New Zealand as they joined in battle for the 34th America’s Cup was truly astonishing. It is surely only a matter of time before future development work will allow a similar quantum leap in performance to be demonstrated in the much more demanding arena of ocean racing.

“Interestingly, Michel Kermarec, a senior aerodynamicist for Oracle, showed us that a solid wing hardly pays. The lift-drag factor is spectacular, but it’s only on a very narrow band and not useful going upwind. A soft sail can still be pretty darn good. I’d love to do a foil-assisted, rather than foil-borne, freestanding rig.”

In fact, Irens is in the midst of working up just such a rig for a 46-foot yawl, Stern, he’s designed that is now being built in Sweden. But that’s a monohull, and we can’t discuss the “dark side” of Irens’s career in a multihull magazine! Rest assured he’s designed some beautiful monohulls. He’s drawn ocean-going fusion schooners (Farfarer, Glaz and Maggie B) and creek-crawling lugger yawls (Romilly and Roxanne). He can draw dayboats, world-girdling liveaboards and sci-fi looking powered trimarans, like ILAN Voyager (Incredibly Long and Narrow) and Cable & Wireless.

There are so many facets to Nigel Irens that it’s impossible to do the man justice in a few words.

There is Irens the Francophile, who lived in La Trinité-sur-Mer, in Brittany, for a few years. He speaks fluent French and with design partner Benoît Cabaret has produced the most exciting Anglo-French flying machines since the Concorde. “I draw the concepts, Benoît verifies and optimizes them,” he says.

Salute Irens the unsung hero. In 2005 he was awarded the highest honour in the UK for industrial design and became one of the Royal Designers for Industry, joining an exclusive club of 200 “members” alongside Apple’s Sir Jonathan Ive and Sir Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the world-wide web.

Meet Irens the analog man. Swedish multihull expert Torbjörn Linderson says: “There is something about working with a person who is “pre digital” and whose performance ideas come from a deep understanding of the yacht as a whole, rather than just numerically driven. And he is just a great guy!” Irens is definitely an analog man without a slide rule. Self-taught and, like Dick Newick, a bit of a seat-of-the-pants designer, his skills are intuitive. “I’m just not a numbers man! I failed miserably at maths as a student.

Design courses didn’t exist in those days, and even if they had, I’m not sure I’d have qualified.” Irens sketches his designs on paper and he can cut out the hull design with scissors and balance the template on the edge of a rule to confirm his ideas. He still makes models.

How about Irens the eccentric? “I sometimes wonder if I am,” he admits. Another sailing journalist characterized his unconventional design palette as “Rembrandt’s Cubist Period” and “Sid Vicious singing opera.”

Spare a thought for Irens the anxious. When you design rocketships sailed across lonely oceans, thousands of miles from land by solo sailors, you can suffer sleepless nights. When

Ellen MacArthur sailed into Falmouth after 71 days he hugged her in relief and exclaimed like a concerned uncle: “Don’t you dare do anything like that again!” Ellen’s verdict on Irens’s B&Q: “She’s in better shape than I am!”

“Nigel is a purist,” adds MacArthur. “If he’s designing a boat to be fast it is fast, and if he’s designing a cruising boat it really does cruise. His boats all have identity, but what sets Nigel apart in my opinion is that all his boats have stunning lines as Nigel is also an artist. To top that he is one of the nicest people I have ever had the pleasure of working with, and I didn’t hesitate one second to put my life in his hands.”

Finally, there’s Irens the dad and family man. To see him sending his kids off to school (Juliette, 16; Katie, 5; Sam, 14), meet his delightful wife, Alison, not to mention Bella the Siamese cat, and join the ritual walk round town with Ellie the springer spaniel is to wonder how he finds time to be a design genius. Clearly, though, he does.

IRENS DESIGNS OVER THE YEARS

1977 - 60-foot cruising trimaran Promenade built for Caribbean charter; still sailing in the BVIs today

1980 - 40-foot racing trimaran Gordano Goose built

1982 - 40-foot racing trimaran IT82 wins its class in Round Britain race

1982 - 50-foot racing catamaran Vital takes third overall in the Route du Rhum

1983 - 80-foot racing catamaran Formule Tag is built; in 1984 she sets new 24 hour record of 512.5 NM

1985 - 60-foot racing trimaran Apricot wins 1985 Round Britain Race with Irens and Tony Bullimore as crew

1986 - 75-foot racing trimaran Fleury Michon VIII takes first overall in Route du Rhum

1987 - 60-foot racing trimarans Fujicolor and Laiterie Mont St Michel launched

1987 - 40-foot Formula 40 catamaran Data General takes second overall in the Formula 40 Championship

1988 - 70-foot power trimaran Ilan Voyager wins Round Britain Powerboat record in 72 hours at an average speed of 21 knots with no fuel stops. 60-foot trimarans Fleury Michon IX and Laiterie Mont St Michel are first and second in the Carlsberg singlehanded transatlantic race

1990 - 60-foot racing tri Fujicolour II launched

1992 - Fujicolor II wins Europe 1 solo Transatlantic Race

1994 - ENZA New Zealand (ex-Formule Tag) wins Jules Verne Trophy as fastest boat to sail non-stop round the world, following a 74-day circumnavigation

1996 - Three Irens designs - Fujicolor II, Region Haute Normandie and Biscuits La Trinitaine

- win all three places in the Europe 1 Single-Handed Race

1998 - 115-foot power trimaran Cable & Wireless launched and sets a new round-the-world record, motoring 22,600 miles in 74 days

2002 - Bayer Crop Science built; it’s one of the first mutihulls built in Nomex sandwich carbon prepreg resin for lightness and rigidity

2004 - 75-foot trimaran B&Q Castorama built for Ellen MacArthur; a year later MacArthur sets a new solo round-the-world record of 71 days 14 hours

2007 - 105-foot trimaran Sodebo, designed for Thomas Coville to beat Ellen MacArthur’s solo record, is launched in Sydney; 97-foot trimaran IDEC 2 is launched for Francis Joyon and sets a new 24-hour solo record of 616 miles

2008 - IDEC 2 sets a new round-the-world solo record of 57 days, 13 hours, smashing the previous record set by MacArthur; Irens is appointed consultant to the Alinghi design team as they prepare to defend the America’s Cup. Sodebo breaks a new 24-hour record of 620.8 miles and establishes a new solo west-east transatlantic record of 5 days 19 hours.

2010 - Oman’s flagship multihull, the 105ft trimaran Oman Air—a sister ship to Sodebo—breaks the non-stop solo Round Britain record in 4 days 15 hours.

2010 - Paradox, a 62ft carbon racer/cruiser trimaran, is built using the molds of Loick Peyron’s trimaran Fujifilm. She averages 300-350 miles a day offshore.

2012 - The SeaRail 19, a production trailable trimaran, is built in Vietnam for the American market.

2013 - The Gunboat 55 and 60 catamarans go into production; Green Marine in the UK start building APC78 (Advanced Performance Catamaran). In Cherbourg, French yard CMM start building three Ocean Eagle 43 fast patrol trimarans from a concept design by Irens.

Francis Joyon smashes the solo west-east Transatlantic record on IDEC II in 5 days, 2 hours and the east-west record in 8 days 16 hours.

Sailing

into an ocean sunset, the Cable & Wireless Adventurer sets a cracking

bio diesel powered pace.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.sailmagazine.com/multihulls/nigel-irens-designs-some-of-the-fastest-racing-multihulls https://www.energy-observer.org/innovations/nigel-irens-its-a-pleasure-to-see-the-new-life-of-the-boat https://www.proboat.com/2022/11/slippery-nigel-irens-launch/ https://www.designboom.com/technology/nigel-irens-cmn-trimaran-explorer-yachts-01-13-2016/ http://www.yachtracingforum.com/forum/team/nigel-irens/ http://www.solarnavigator.net/nigel_irens.htm http://solarnavigator.net/history/cable_and_wireless.htm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nigel_Irens http://www.nigelirens.com/

|