|

PLAN

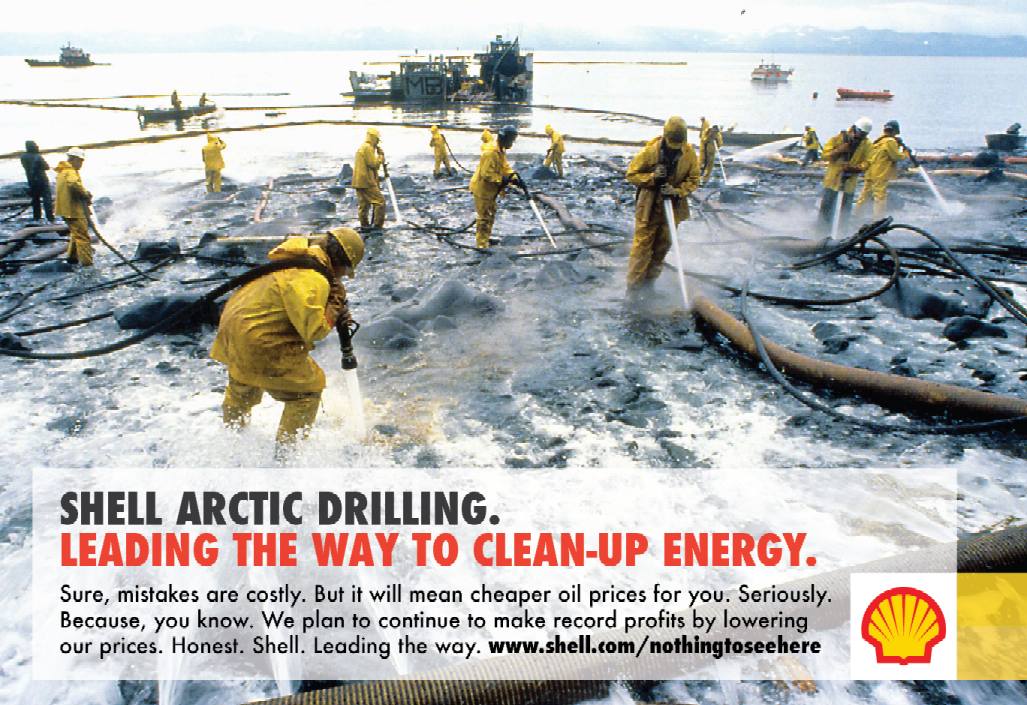

TO FAIL - Environmental groups strongly opposed Arctic offshore

drilling. They targeted drill and support vessels for protests. Greenpeace activists in early April boarded the Blue Marlin, a heavy-lift ship carrying the Polar Pioneer across the Pacific Ocean to the United States. They left after six days.

Seattle protesters in kayaks, dubbed "kayaktivists," took to the water to demonstrate against the Polar Pioneer when it was docked in the city. Greenpeace USA protesters in Portland, Oregon, hung from a bridge over the Willamette River and briefly delayed a support vessel that had undergone repairs.

Greenpeace spokesman Travis Nichols said by email that he was not aware of any additional protests planned.

CLIMATE

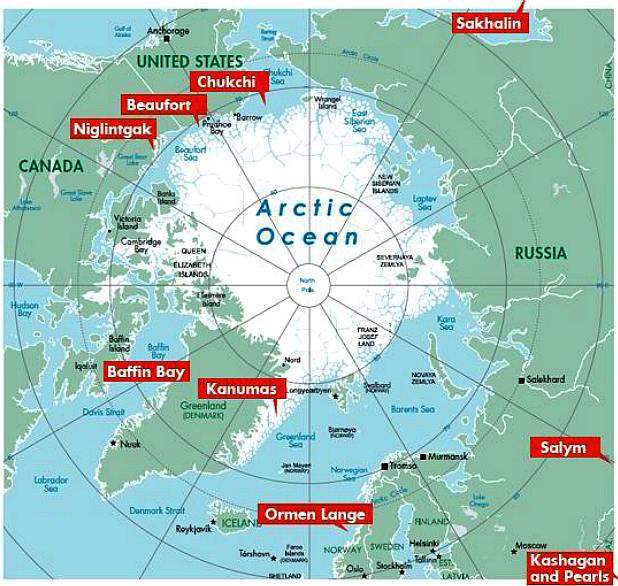

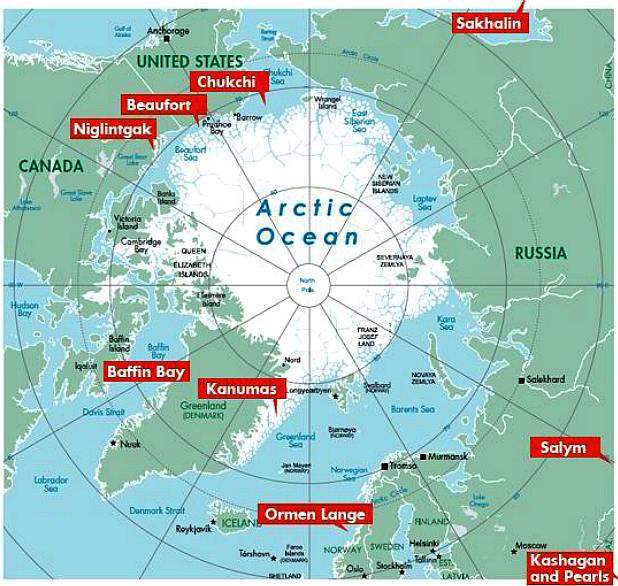

CHAOS - The Arctic holds around 30 per cent of the world's undiscovered natural gas and 13 per cent of yet to find oil, according to Shell.

This amounts to around 400 billion barrels of oil and 10 times the total oil and gas produced to date in the North Sea.

Shell has said that developing the area is essential for securing energy supplies of the future.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) said that it acted after reviewing thousands of comments from the public, Alaska Native organisations and state and federal agencies.

“We have taken a thoughtful approach to carefully considering potential exploration in the Chukchi Sea, recognising the significant environmental, social and ecological resources in the region and establishing high standards for the protection of this critical ecosystem, our Arctic communities, and the subsistence needs and cultural traditions of Alaska Natives,” said BOEM director Abigail Ross Hopper.

“As we move forward, any offshore exploratory activities will continue to be subject to rigorous safety standards.”

Shell must still obtain other permits from state and federal agencies, including one to drill from the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement.

The company must also obtain government opinions that find Shell can comply with terms and conditions of the Endangered Species Act.

SHELL

DRILLING OCTOBER 13 2015,

ANCHORAGE

Two drill vessels employed by Royal Dutch Shell PLC off Alaska's northwest coast have safely departed Arctic waters for the Pacific Northwest.

The 572-foot Noble Discoverer, owned by Noble Drilling U.S. LLC, reached Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands on Sunday afternoon. After a Coast Guard inspection, the vessel departed Monday for the Port of Everett in Washington state. A spokesman for Shell, Curtis Smith is quoted as saying.

The Polar Pioneer, owned by Transocean Ltd., reached Dutch Harbor on Monday afternoon. Two tug boats accompanying the semi-submersible drilling vessel, the Ocean Wind and Ocean Wave vessel, planned to refuel and change crews. The Polar Pioneer will be towed to Port Angeles, Washington.

There was also the near collapse of oil prices from about $150 per barrel in 2008 (when Shell purchased its leases) to less than $45 this past summer. Despite all this, Shell had publicly renewed its commitment to the Arctic as recently as mid-September. In an interview with the BBC, Ben van Beurden, Shell's chief executive officer, said production would not take place until at least 2030, thereby allowing the company to avoid having to sell the oil at the current low prices or lowering the price further by adding more product to an already saturated market. It is a stalling tactic that was echoed one week later by Exxon Mobil’s senior Arctic consultant, Jed Hamilton, who said, “American oil companies should explore for crude in Arctic waters so they can bring it up by the time the nation’s shale oil fields have been mostly drained, in two decades.”

SHELL

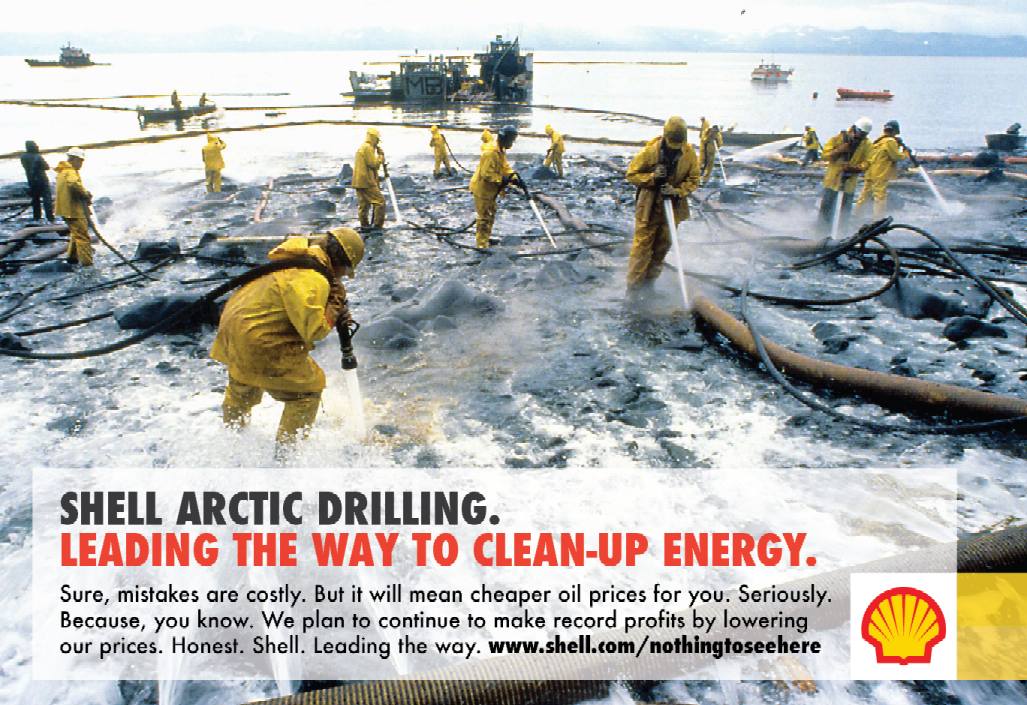

EXPLORATION - 2012 was supposed to be a banner year for Royal Dutch Shell, as the company planned to embark on the first Arctic offshore exploratory drilling activity in decades and set itself up to make billions of dollars prospecting for oil in the far-flung region off Alaska’s North Slope. But that’s not how things turned out.

Instead, beginning with efforts to prepare for operations, the company experienced one setback after another. Shell struggled to meet the government’s safety requirements for its oil spill response equipment, experiencing multiple technical failures and permit violations. Mother Nature weighed in and kept the drilling sites choked with sea ice. Yet despite these setbacks and others, Shell received permits from the federal government in August to begin preparatory drilling, albeit not deep enough to actually strike oil in Alaska’s Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

The coup de grace came on New Year’s Eve when Shell’s Kulluk rig ran aground near Kodiak, Alaska — a fiasco that required a 500-plus person response effort, led by the Coast Guard, working for more than a week in dangerous conditions to secure the rig. This final calamity prompted the Obama administration to launch a high-level 60-day review of Shell’s entire Arctic drilling program, and after assessing its equipment and determining that both Arctic drilling rigs were too damaged to operate in 2012, caused Shell to announce on February 27 that it would not seek to drill in the remote and challenging region in 2013.

Shell announced on September 28 2015 that it would cease further exploration in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas after spending upward of $7 billion.

The results from an exploratory well drilled about 80 miles off Alaska's northwest coast in the Chukchi sea proved to be

disappointing. The federal regulatory environment is also unpredictable. Federal regulators required two drill vessels in Arctic drilling areas so that a relief well could be quickly drilled after a well blowout.

The exploratory well found oil and gas but not in quantities that justified the huge expense of Arctic drilling, where Shell backed up its rigs with a flotilla of support and safety vessels and made regular helicopter flights from a staging area 150 miles away in Barrow, the country's northernmost community.

Shell last drilled in Alaska's northern waters in 2012 and experienced significant problems with vessels in transit after drilling ended.

The Kulluk, a 266-foot circular drill vessel owned by Shell with a reinforced hull, broke loose from its tow vessel in gale-force December winds in the Gulf of Alaska. Efforts to control the vessel failed. The Kulluk ran aground near Kodiak Island on Dec. 31, 2012. The vessel was eventually scrapped.

The Noble Discoverer, built as a logging ship in 1965 and converted to a drill ship in 1976, in 2012 was found to be in violation of

pollution and safety maritime law.

Crew members had dismantled an oil-water separator, a device that removes petroleum from bilge water before it's dumped overboard. The crew also failed to inform the Coast Guard of on-board back fires, high levels of exhaust and

fuel leaks in violation of safety laws. Following a Coast Guard investigation, Noble Drilling pleaded guilty to eight felonies and was fined $12.2 million.

PLASTIC

POLLUTION - Almost 1/2 of the plastic we use, we use just once, and then we throw it away. The problem is, there is no away. Every piece of plastic ever made is still in existence today. 100 million tons of plastic are manufactured every year for products that are used for less than 5 minutes. This is why shifting away from the modern convinces that plastic provides is a dynamic situation, with many layers stacking in from different sides of the equation. The convenience of the plastic straw has become a thoughtless part of our every day life, and we aren’t aware that the little straws will end up in our land fills, road sides, water ways and oceans. The Environmental Protection Agency tells us that only 9 percent of plastic bags are recycled in the US, and a mere 7% of ALL plastics end up being recycled. Often times, plastic can’t recycled into the same type of plastic. Once plastic is used as a water bottle, it can never be a plastic water bottle again. Products that are made from recycled plastic don’t stay recyclable because the product is a mixture of different types of plastic, which causes structural weakness in the resulting material, rendering it useless. So it comes as a little surprise that our oceans are becoming a plastic graveyard that’s growing every year.

MICRO

PLASTICS IN ARCTIC WATERS AND ICE - 8 OCT 2015

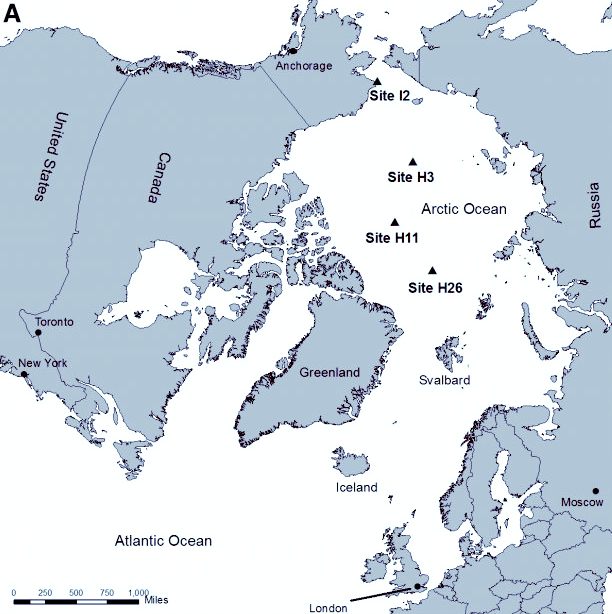

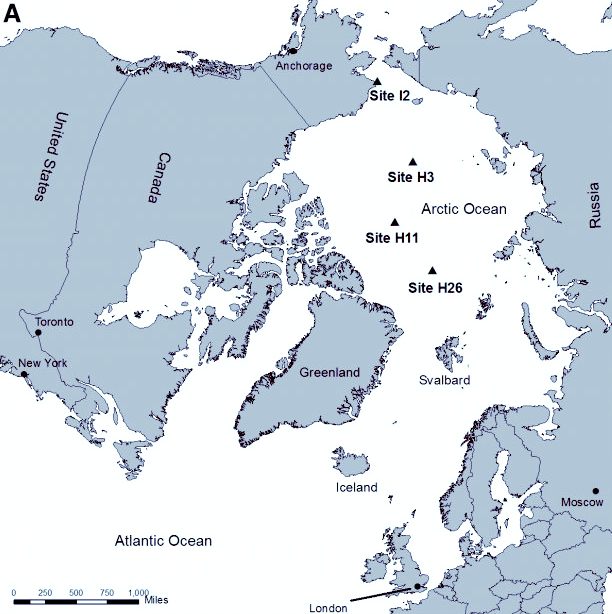

Microplastics, the tiny plastic particles that are accumulating in marine waters and big lakes around the world, are now showing up in the Arctic waters south and southwest of Svalbard, Norway, a new study says.

The study, published in the open-access journal Nature Scientific

Reports, is the first documentation of microplastics in those waters, raising concerns that the tiny pieces of plastic litter are entering the Arctic food web.

Water samples taken during a June 2014 research cruise showed that microplastics are ubiquitous in that region. Nearly all of the water samples wound up containing microplastics, the researchers found.That was the case for water samples were taken at the surface and for those taken, with the use of pumps, six meters below the surface, though the deeper waters held a much higher concentration of microplastics, the study by scientists from

Ireland and Italy found.

Ninety-five percent of the measured microplastics were fibers, suggesting they were broken-down pieces of larger plastic items from aboard ships or used for

fishing, recreation or industrial activities, that subsequently traveled very long distances to the

waters off Svalbard, the study says

- though local sources, such as regional sewage disposal, could also be contributing to the load.

Lead scientist Amy Lusher of the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology and collaborating scientist Valentina Tirelli of the National Institute of Oceanography and Experimental Geophysics in Italy, said they were surprised by the findings. "We had originally assumed the Arctic may be an unpolluted area, however, as you can see, this is not the case," they said in an email.

When you can scoop up more plastic than actual biomass from the ocean, it’s clear there is a relevant problem. Currently, there is a garbage patch in every major ocean across the globe, which totals to five large plastic gyres, and six additional smaller ones. They continue to grow as we produced millions of tons of disposable plastic product each year. The plastic products slowly break down in our oceans from wave action, sun and wind degradation. The now smaller fragments are mistakenly consumed for food by birds and fish. The micro-plastics collect inside the digestive tract of the marine life, causing starvation, dehydration, and often times death. When the belly is full of plastic, the fish isn’t hungry because of the false feeling of being full. If it does eat, there are problems with vital nutrient absorption and excretion. It is estimated that 267 marine species are known to have been entangled or severely suffered from ingesting plastic. The whole marine ecosystem gets affected, sea

turtles,

fish, sea birds,

whales, coral reefs and other immobile living organisms.

The microplastic bits they found averaged 1.9 millimeters and were difficult to see without a microscope, they said.

While some microplastics are pieces of larger items, others are flushed into water bodies through the use of personal-care and household products. Many of those products, such as facial scrubs and toothpastes, contain small plastic beads used by manufacturers for their exfoliating or scrubbing qualities.

With Arctic sea ice diminishing and Arctic marine traffic increasing, more work is needed to understand how much of this plastic litter is coming to northern waters and how it might be ingested by

fish and other marine life, the new study says.

“Considering the potential implications of microplastics, there is an urgent need to assess the levels in the Arctic,” it says.

While this was the first measurement of microplastics in waters off Svalbard, other studies have found such plastic litter in far-flung sites.

A Dartmouth scientist examining tiny marine organisms dwelling in sea ice in the central Arctic Ocean was surprised to find numerous types of bright-colored plastic bits also embedded in the ice. Dartmouth’s Rachel Obbard described her findings in a study published last year in the journal Earth’s Future.

Microplastics have been found in areas ranging from the Great Lakes to Arctic marine waters off Canada to the Baltic Sea.

JOHN

KERRY - US TO ADD STATE REPRESENTATIVE - FEB 2014

In a press release announcing a new U.S. Department of State position to address

Arctic matters, Secretary of State

John Kerry identified the Arctic as “the last global frontier and a region with enormous and growing geostrategic, economic, climate, environment and national security implications for the United States and the world.”

Secretary Kerry announced that the State Department will add a Special Representative for the Arctic Region, a high-level official of stature who will play a critical role in advancing American interests in the Arctic Region, particularly as it prepares efforts for the United States to Chair the Arctic Council in 2015.

“President Obama and I are committed to elevating our attention and effort to keep up with the opportunities and consequences presented by the Arctic’s rapid transformation—a very rare convergence of almost every national priority in the most rapidly-changing region on the face of the earth,” Kerry said.

He continued, “The great challenges of the Arctic matter enormously to the United States, and they hit especially close to home for Alaska, which is why it is no wonder that Senator Begich’s very first piece of legislation aimed to create an Arctic Ambassador, or why as Foreign Relations Committee Chairman I enjoyed a close partnership with Senator Murkowski on a treaty vital to

energy and maritime interests important to Alaska. Going forward, I look forward to continuing to work closely with Alaska’s Congressional delegation to strengthen America’s engagement in Arctic issues.”

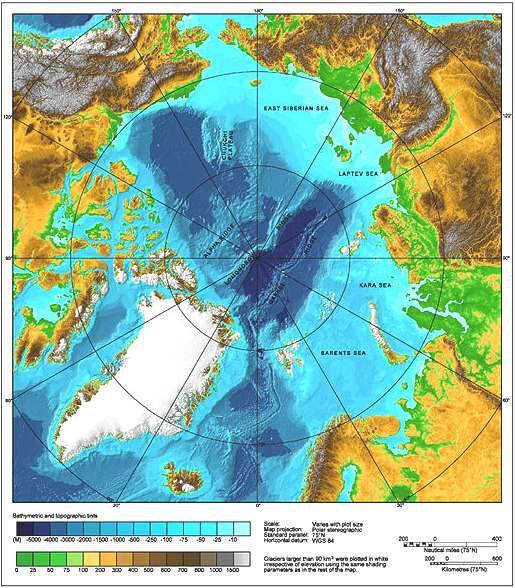

GEOGRAPHY

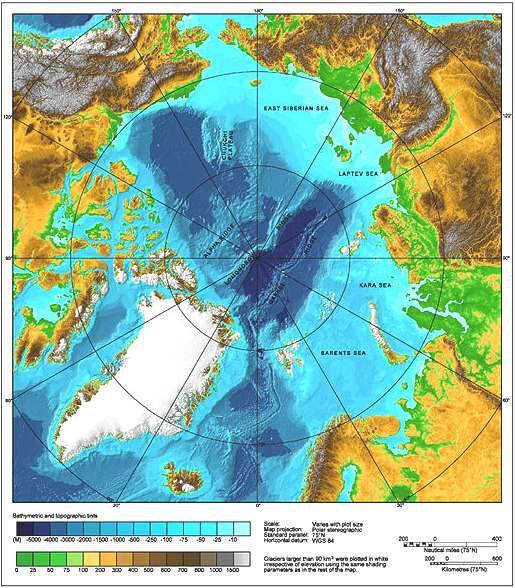

The Arctic

Ocean is located in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Arctic north polar

region. It is the smallest and shallowest of the world's five major oceanic divisions. The

International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) recognizes it as an ocean, although some oceanographers call it the Arctic Mediterranean Sea or simply the Arctic Sea, classifying it a mediterranean sea or an estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. Alternatively, the Arctic Ocean can be seen as the northernmost part of the all-encompassing World Ocean.

Almost completely surrounded by Eurasia and North America, the Arctic Ocean is partly covered by sea ice throughout the

year (and almost completely in winter). The Arctic Ocean's temperature and salinity vary seasonally as the ice cover melts and freezes; its salinity is the lowest on average of the five major oceans, due to low evaporation, heavy freshwater inflow from rivers and streams, and limited connection and outflow to surrounding oceanic waters with higher salinities. The summer shrinking of the ice has been quoted at 50%. The US National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) uses satellite data to provide a daily record of Arctic sea ice cover and the rate of melting compared to an average period and specific past years.

The Arctic Ocean occupies a roughly circular basin and covers an area of about 14,056,000 km2 (5,427,000 sq mi), almost the size of Russia. The coastline is 45,390 km (28,200 mi) long. It is surrounded by the land masses of Eurasia, North America, Greenland, and by several islands.

It is generally taken to include Baffin Bay, Barents Sea, Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea, East Siberian Sea, Greenland Sea, Hudson Bay, Hudson Strait, Kara Sea, Laptev Sea, White Sea and other tributary bodies of water. It is connected to the Pacific Ocean by the Bering Strait and to the Atlantic Ocean through the Greenland Sea and Labrador Sea.

Arctic shelves

The ocean's Arctic shelf comprises a number of continental shelves, including Canadian Arctic shelf, underlying the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, and the Russian continental shelf, which is sometimes simply called the "Arctic Shelf" because it is greater in extent. The Russian continental shelf consists of three separate, smaller shelves, the Barents Shelf, Chukchi Sea Shelf and Siberian Shelf. Of these three, the Siberian Shelf is the largest such shelf in the world. The Siberian Shelf holds large

oil and gas reserves, and the Chukchi shelf forms the border between Russian and the United States as stated in the USSR–USA Maritime Boundary Agreement. The whole area is subject to international territorial claims.

Underwater features

An underwater ridge, the Lomonosov Ridge, divides the deep sea North Polar Basin into two oceanic basins: the Eurasian Basin, which is between 4,000 and 4,500 m (13,000 and 14,800 ft) deep, and the Amerasian Basin (sometimes called the North American, or Hyperborean Basin), which is about 4,000 m (13,000 ft) deep. The bathymetry of the ocean bottom is marked by fault-block ridges, abyssal plains, ocean deeps, and basins. The average depth of the Arctic Ocean is 1,038 m (3,406 ft). The deepest point is Litke Deep in the Eurasian Basin, at 5,450 m (17,880 ft).

The two major basins are further subdivided by ridges into the Canada Basin (between Alaska/Canada and the Alpha Ridge), Makarov Basin (between the Alpha and Lomonosov Ridges), Fram Basin (between Lomonosov and Gakkel ridges), and Nansen Basin (Amundsen Basin) (between the Gakkel Ridge and the continental shelf that includes the Franz Josef Land).

The

Arctic Ocean world location map

ENVIRONMENTAL

The Arctic ice pack is thinning, and in many years there is also a seasonal hole in the ozone layer. Reduction of the area of Arctic sea ice reduces the planet's average albedo, possibly resulting in global warming in a positive feedback mechanism. Research shows that the Arctic may become ice free for the first time in

human history by 2040.

Warming temperatures in the Arctic may cause large amounts of fresh meltwater to enter the North Atlantic, possibly disrupting global ocean current patterns. Potentially severe changes in the Earth's

climate might then ensue.

As the extent of sea ice diminishes and sea level rises, the effect of storms such as the Great Arctic Cyclone of 2012 on open water increases, as does possible salt-water damage to vegetation on shore at locations such as the Mackenzie River River delta as stronger storm surges become more likely.

Other environmental concerns relate to the radioactive contamination of the Arctic Ocean from, for example, Russian radioactive waste dump sites in the Kara Sea and Cold War

nuclear test sites such as Novaya Zemlya. In addition, Shell planned to drill exploratory wells in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas during the summer of 2012, which environmental groups filed a lawsuit about in an attempt to protect native communities, endangered wildlife, and the Arctic Ocean in the event of a major oil spill.

Plastic

pollution has reached the Arctic and Antarctic regions, killing the

wildlife upon which larger predators like the polar bear rely on for food.

We are working on a vehicle

that could help clean Arctic waters, by sweeping the 5 main ocean gyres of

the majority of garbage. You can make a difference immediately, by

disposing of your plastic waste responsibly, and by contributing to

organisations that will help fund our not for profit research.

Polar bears live in one of the planet's coldest environments and depend on a thick coat of insulated fur, which covers a warming layer of fat. Fur even grows on the bottom of their

paws. The bear's stark white coat provides camouflage in surrounding snow and ice. But under their fur, polar bears have black skin—the better to soak in the sun's warming rays.

Polar bears are powerful predators that do not normally fear humans, which can make them dangerous. Near human settlements, they often acquire a taste for garbage, bringing bears and humans

dangerously close, and putting the bears at risk from toxic waste.

Over 80% of marine pollution comes from land-based activities.

From plastic bags to pesticides - most of the waste we produce on land eventually reaches the oceans, either through deliberate dumping or from run-off through drains and rivers.

Plastic garbage, which decomposes very slowly, is often mistaken for food by marine animals. High concentrations of plastic material, particularly plastic bags, have been found blocking the breathing passages and stomachs of many marine species, including whales, dolphins, seals, puffins, and turtles. Plastic six-pack rings for drink bottles can also choke marine animals.

This garbage can also come back to shore, where it pollutes beaches and other coastal habitats.

OCEANOGRAPHIC

The Arctic Ocean contains a major choke point in the southern Chukchi Sea, which provides access to the Pacific Ocean through the Bering Strait between

Alaska and Eastern Siberia. Subject to ice conditions, the Arctic Ocean provides the shortest marine link between the extremes of eastern and western Russia. There are several floating research stations in the Arctic, operated by the U.S. and

Russia.

The greatest inflow of water comes from the Atlantic by way of the Norwegian Current, which then flows along the Eurasian coast. Water also enters from the

Pacific via the Bering

Strait. The East Greenland Current carries the major outflow.

Ice covers most of the ocean surface year-round, causing subfreezing air temperatures much of the time. The Arctic is a major source of very cold air that moves toward the equator, meeting with warmer air at latitude 60°N and causing rain and snow. This flow is the lower portion of the polar cell, the highest (by latitude) of the three principal circulation cells of the Earth's atmosphere each spanning thirty degrees of latitude. Marine life abounds in open areas, especially the more southerly waters. The ocean's major ports are the cities of Murmansk, Arkhangelsk and Prudhoe Bay.

In large parts of the Arctic Ocean, the top layer (about 50 m) is of lower salinity and lower temperature than the rest. It remains relatively stable, because the salinity effect on density is bigger than the temperature effect. It is fed by the freshwater input of the big Siberian and Canadian streams (Ob, Yenissey, Lena, MacKenzie), the water of which quasi floats on the saltier, denser, deeper ocean water. Between this lower salinity layer and the bulk of the ocean lies the so-called halocline, in which both salinity and temperature are rising with increasing depth.

Any convection eddies caused by the temperature difference between the cold ocean surface and the warmer depth stop at this thermocline, leaving only heat conduction as upward heat transport mechanism, which is orders of magnitude smaller. Without this insulation effect, there would be much less Arctic sea ice. The salinity and temperature pattern of the Arctic Ocean can be quite complex, being dependent on the different flows into and out of the Arctic region.

SEA ICE

Much of the Arctic Ocean is covered by sea ice which varies in extent and thickness seasonally. The mean extent of the ice is decreasing since 1980 from the average winter value of 15,600,000 km2 (6,023,200 sq mi) at a rate of 3% per decade. The seasonal variations are about 7,000,000 km2 (2,702,700 sq mi) with the maximum in April and minimum in September. The sea ice is affected by wind and ocean currents which can move and rotate very large areas of ice. Zones of compression also arise, where the ice piles up to form pack ice.

Icebergs occasionally break away from northern Ellesmere Island, and icebergs are formed from glaciers in western Greenland and extreme northeastern Canada. These icebergs pose a hazard to ships, most famously the

Titanic. Permafrost is found on most islands. The ocean is virtually icelocked from October to June, and ships are subject to superstructure icing from October to May. Before the advent of modern icebreakers, ships sailing the Arctic Ocean risked being trapped or crushed by sea ice (although the Baychimo drifted through the Arctic Ocean untended for decades despite these hazards).

CLIMATE

Under the influence of the Quaternary glaciation, the Arctic Ocean is contained in a polar climate characterized by persistent cold and relatively narrow annual temperature ranges. Winters are characterized by continuous darkness (polar night), cold and stable weather conditions, and clear skies; summers are characterized by continuous daylight (midnight sun), damp and foggy weather, and weak

cyclones with rain or

snow.

The temperature of the surface of the Arctic Ocean is fairly constant, near the freezing point of seawater. Because the Arctic Ocean consists of saltwater the temperature must reach −1.8°C before freezing occurs. The density of sea water, in contrast to fresh water, increases as it nears the freezing point and thus it tends to sink. It is generally necessary that the upper 100–150 meters of ocean water cools to the freezing point for sea ice to form. In the winter the relatively warm ocean

water exerts a moderating influence, even when covered by ice. This is one reason why the Arctic does not experience the extreme temperatures seen on the Antarctic continent.

There is considerable seasonal variation in how much pack ice of the Arctic

ice pack covers the Arctic Ocean. Much of the Arctic ice pack is also covered in snow for about 10 months of the year. The maximum snow cover is in March or April — about 20 to 50 cm (7.9 to 20 in) over the frozen ocean.

The climate of the Arctic region has varied significantly in the past. As recently as 55 million years ago, during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum, the region reached an average annual temperature of 10–20 °C (50–68 °F). The surface waters of the northernmost Arctic ocean warmed, seasonally at least, enough to support tropical

life forms requiring surface temperatures of over 22 °C (72 °F).

NATURAL RESOURCES

Petroleum and natural gas fields, placer deposits, polymetallic nodules, sand and gravel aggregates, fish, seals and whales can all be found in abundance in the region.

The political dead zone near the center of the sea is also the focus of a mounting dispute between the United States, Russia,

Canada,

Norway, and

Denmark. It is significant for the

global energy market because it may hold 25% or more of the world's undiscovered oil and gas resources.

FAUNA and FLORA

Endangered marine species in the Arctic Ocean include walruses and whales. The area has a fragile ecosystem which is slow to change and slow to recover from disruptions or damage. Lion's mane jellyfish are abundant in the waters of the Arctic, and the banded gunnel is the only species of gunnel that lives in the ocean.

The Arctic Ocean has relatively little plant life except for phytoplankton. Phytoplankton are a crucial part of the ocean and there are massive amounts of them in the Arctic, where they feed on nutrients from rivers and the currents of the

Atlantic and Pacific oceans. During summer, the Sun is out day and night, thus enabling the phytoplankton to photosynthesize for long periods of time and reproduce quickly. However, the reverse is true in winter where they struggle to get enough light to survive.

NOAA

survey ship Fairweather - Arctic 2012

ARCTIC

HISTORY

For much of European history, the North Polar regions remained largely unexplored and their geography conjectural. Pytheas of Massilia recorded an account of a journey northward in 325 BC, to a land he called "Eschate Thule," where the Sun only set for three hours each day and the water was replaced by a congealed substance "on which one can neither walk nor sail." He was probably describing loose sea ice known today as "growlers" or "bergy bits;" his "Thule" was probably Norway, though the Faroe Islands or Shetland Island have also been suggested.

Early cartographers were unsure whether to draw the region around the North Pole as land (as in Johannes Ruysch's map of 1507, or Gerardus Mercator's map of 1595) or water (as with Martin Waldseemüller's world map of 1507). The fervent desire of European merchants for a northern passage to "Cathay" (China) caused water to win out, and by 1723 mapmakers such as Johann Homann featured an extensive "Oceanus Septentrionalis" at the northern edge of their charts.

The few expeditions to penetrate much beyond the Arctic Circle in this era added only small islands, such as Novaya Zemlya (11th century) and Spitsbergen (1596), though since these were often surrounded by pack-ice, their northern limits were not so clear. The makers of navigational charts, more conservative than some of the more fanciful cartographers, tended to leave the region blank, with only fragments of known coastline sketched in.

This lack of knowledge of what lay north of the shifting barrier of ice gave rise to a number of conjectures. In England and other European nations, the myth of an "Open Polar Sea" was persistent. John Barrow, longtime Second Secretary of the British Admiralty, promoted exploration of the region from 1818 to 1845 in search of this.

In the United States in the 1850s and 1860s, the explorers Elisha Kane and Isaac Israel Hayes both claimed to have seen part of this elusive body of water. Even quite late in the century, the eminent authority Matthew Fontaine Maury included a description of the Open Polar Sea in his textbook The Physical Geography of the Sea (1883). Nevertheless, as all the

explorers who

traveled closer and closer to the pole reported, the polar ice cap is quite thick, and persists year-round.

Fridtjof Nansen was the first to make a nautical crossing of the Arctic Ocean, in 1896. The first surface crossing of the ocean was led by Wally Herbert in 1969, in a

dog sled expedition from Alaska to Svalbard, with

air support. The first nautical transit of the north pole was made in 1958 by the

submarine

USS

Nautilus, and the first surface nautical transit occurred in 1977 by the icebreaker NS Arktika.

Since 1937, Soviet and Russian manned drifting ice stations have extensively monitored the Arctic Ocean. Scientific settlements were established on the drift ice and carried thousands of

kilometres by ice floes.

Oceans

of the world location map

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BAY BENGAL - BERING

- CARIBBEAN - CORAL - EAST

CHINA

SEA

ENGLISH CH

-

GOC - GULF

GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO

- INDIAN

-

IOC

-

IRC - MEDITERRANEAN -

NORTH SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN GULF

RED

SEA - SEA

JAPAN - STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE - SOUTHERN

- UNCLOS

- UNEP

WOC

- WWF

AMAZON

- BURIGANGA - CITARUM - CONGO - CUYAHOGA

-

GANGES - IRTYSH

- JORDAN - LENA -

MANTANZA-RIACHUELO

MARILAO

- MEKONG - MISSISSIPPI - NIGER - NILE - PARANA - PASIG - SARNO - THAMES

- YANGTZE - YAMUNA - YELLOW

LINKS

& REFERENCE

http://blog.geogarage.com/2012_07_29_archive.html

http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/news/features/july12/fairweather.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantic_Ocean

National

Geographic polar-bear WWF

World Wildlife Fund blue_planet

pollution Charterworld

news Tara expeditions http://www.nature.com/articles/srep14947

http://www.charterworld.com/news/tag/tara-expeditions

http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/blue_planet/problems/pollution/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arctic_Ocean

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/polar-bear/

http://www.enterprise-europe-scotland.com/sct/news/?newsid=4538

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Convention_for_the_Safety_of_Life_at_Sea

PATENT

PENDING - Imagine a vessel that can recover ocean plastic and

recycle it as filler for new products, or a clean marine diesel. The proof

of concept boat above can do this. It is to be displayed at Innovate 2015

in London on November 9-10.

|