|

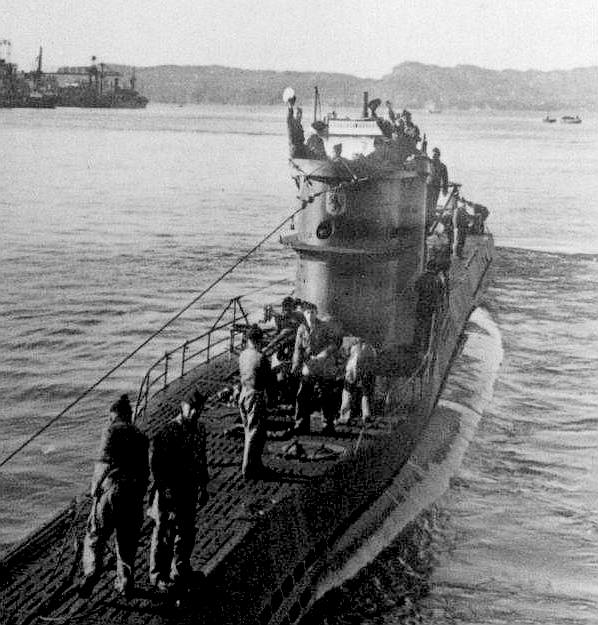

U995 Kiel Marine Museum

- a magnificent example, well preserved

WWII U-BOAT SUBMARINE WRECK FOUND - 21

OCTOBER 2014, NORTH CAROLINA

German U-boat 576 and freighter Bluefields found within 240 yards

A team of researchers led by NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries have discovered two significant vessels from World War II’s Battle of the Atlantic. The German U-boat 576 and the freighter Bluefields were found approximately 30 miles off the coast of North Carolina. Lost for more than 70 years, the discovery of the two vessels, in an area known as the Graveyard of the

Atlantic, is a rare window into a historic military battle and the underwater battlefield landscape of WWII.

“This is not just the discovery of a single shipwreck,” said Joe Hoyt, a NOAA sanctuary scientist and chief scientist for the expedition. “We have discovered an important battle site that is part of the Battle of the Atlantic. These two ships rest only a few hundred yards apart and together help us interpret and share their forgotten stories.”

On July 15, 1942, Convoy KS-520, a group of 19 merchant ships escorted by the

U.S. Navy and Coast Guard, was en route to Key West, Florida, from Norfolk, Virginia, to deliver cargo to aid the war effort when it was attacked off Cape Hatteras. The U-576 sank the Nicaraguan flagged freighter Bluefields and severely damaged two other ships. In response,

U.S. Navy Kingfisher aircraft, which provided the convoy’s air cover, bombed U-576 while the merchant ship Unicoi attacked it with its deck gun. Bluefields and U-576 were lost within minutes and now rest on the seabed less than 240 yards apart.

“Most people associate the Battle of the Atlantic with the cold, icy waters of the North Atlantic,” said David Alberg, superintendent of NOAA’s Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. “But few people realize how close the war actually came to America’s shores. As we learn more about the underwater battlefield, Bluefields and U-576 will provide additional insight into a relatively little-known chapter in American history.”

The discovery of U-576 and Bluefields is a result of a 2008 partnership between NOAA and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to survey and document vessels lost during WWII off the North Carolina coast. Earlier this year, in coordination with Monitor National Marine Sanctuary, NOAA Ship Okeanos Explorer conducted an initial survey based on archival research. In August, archaeologists aboard NOAA research vessel SRVX Sand Tiger located and confirmed the ships’ identities.

“This discovery highlights the importance of federal agencies working together to identify and protect these unique submerged archaeological resources that are of local and international importance,” said William Hoffman, a BOEM archaeologist.

WWII

U-BOAT ATTACK SS CITY OF CAIRO - Shortly after a second torpedo struck

this ship, the silver rupees onboard plummeted to the bottom of the

Atlantic. They have now been recovered by salvers in April 2015. The last remnants of the City of Cairo disappeared beneath the

waves 73 years ago. The U-boat surfaced and approached the survivors'

lifeboats.

Its captain, Karl-Friedrich Merten, famously directed them to the nearest land and said:

"Goodnight. Sorry for sinking you." Only six of 311 people aboard died in the sinking, but it would be three weeks before anyone found any of the six lifeboats that had set out for land. In that time, 104 of the 305 survivors died.

The British SS Clan Alpine picked up 154 survivors alive on the way to St Helena and a further 47 were rescued by a British merchant ship, the Bendoran, and taken to Cape Town.

A final lifeboat was discovered 51 days after the sinking, off the coast of South America, with only two of its many passengers alive. In a cruel twist of fate, one of the two men, Third Officer James Allister Whyte, died shortly after when the ship taking him home was torpedoed by another U-boat.

The newly identified wrecks are protected under international law. Although Bluefields did not suffer any casualties during the sinking, the wreck site is a war grave for the crew of U-576.

“In legal succession to the former German Reich, the Federal Republic of

Germany, as a rule, sees itself as the owner of formally Reich-owned military assets, such as ship or aircraft wreckages,” said the

German Foreign Office in a statement. “The Federal Republic of Germany is not interested in a recovery of the remnants of the U-576 and will not participate in any such project. It is international custom to view the wreckage of land, sea, and air vehicles assumed or presumed to hold the remains of fallen soldiers as war graves. As such, they are under special protection and should, if possible, remain at their site and location to allow the dead to rest in peace.”

United States policy on sunken state vessels, such as these, reaffirms sovereign government ownership of the wrecks, including German ownership of U-576. As stated in the 2001 Presidential Statement on United States Policy for the Protection of Sunken State Craft the wrecks are not considered abandoned nor does passage of time change their ownership.

Those who would engage in unauthorized activities directed at sunken State craft are advised that disturbance or recovery of such craft should not occur without the express permission of the sovereign government retaining ownership, NOAA said, adding, the United States will use its authority to protect and preserve sunken State craft of the United States and other nations.

Other partners who participated in this effort include: NOAA’s Office of Exploration and Research; the National Park Service American Battlefield Protection Program and Submerged Resource Center; East Carolina University, the University of North Carolina Coastal Studies Institute; and SRI International.

As part of the NOAA Battle of the Atlantic Research Project, extensive discussions took place with others including consultation with both Great Britain and Germany as well as the United States Navy and United States Coast Guard. State of the art marine technology provided high-resolution sonar imagery to corroborate historic and archival accounts of the final location and characteristics of each vessel.

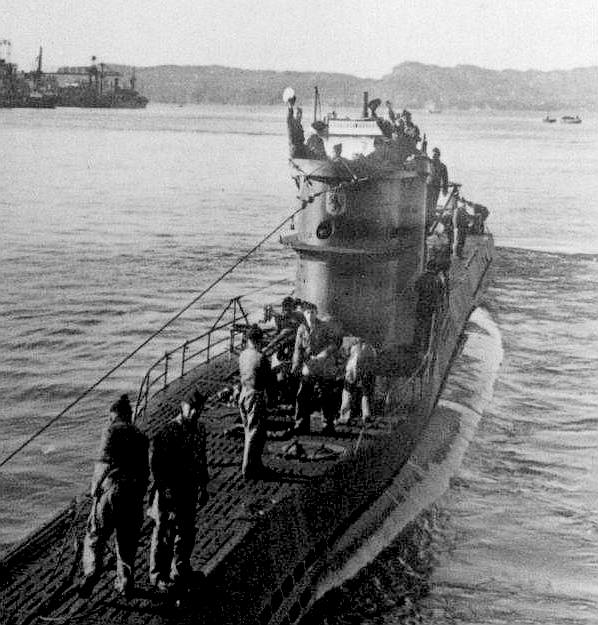

The German

submarine U-576 (Circa 1940-42) departs from Saint-Nazaire, France, on the Atlantic

coast. The submarine was sunk in 1942 by aircraft fire after attacking and sinking the Nicaraguan freighter Bluefields and two other ships off North Carolina.

WHAT'S

IN A NAME

The

term 'U-boat' is the anglicized version of the German word U-Boot, a shortening of Unterseeboot, which means "undersea boat". While the German term refers to any submarine, the English

description (as with many other languages) refers specifically to military submarines operated by

Germany during World War I and World War II. Austro-Hungarian submarines of World War I (and before) were also known as U-boats.

U-boats

were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, but they were

far most effectively used in an economic warfare role (commerce raiding), enforcing a naval blockade against enemy shipping. The primary targets of the U-boat campaigns in both wars were the merchant convoys bringing supplies from Canada, the British Empire and the United States to the islands of Great Britain and (during

World War II) to the Soviet Union and the Allied Countries in the Mediterranean.

This policy though backfired, inevitably bringing other countries into

conflicts.

TURN

OF THE CENTURY DEVELOPMENT

The first submarine built in Germany was the three-man submarine Brandtaucher, which sank to the bottom of Kiel harbor during its first test dive. The vessel was designed in 1850 by the inventor and engineer Wilhelm Bauer and built by Schweffel & Howaldt in Kiel for the Imperial German Navy. Brandtaucher was later rediscovered during dredging operations in 1887, and subsequently raised sixteen years later and placed in a museum in Germany, where it remains today.

It is unclear if the crew died during the test dive.

This was followed in 1890 by W1 and W2, built to a Nordenfelt design. In 1903, Germaniawerft dockyard in Kiel completed Germany's first fully functional submarine, Forelle which was sold to Russia during the Russo-Japanese War in April 1904. The SM U-1 was a completely redesigned Karp-class submarine and only one was built. It was commissioned by the Imperial German Navy on 14 December 1906. It had a double hull, was powered by a Körting kerosene engine and was armed with a single torpedo tube. The fifty percent larger SM U-2 had two torpedo tubes. A

diesel engine was not installed in a German navy boat until the U-19 class of 1912–13. At the start of World War I, Germany had 48 submarines of 13 classes in service or under construction. During the

First World War the SM U-1 was used for training and was retired in 1919. It is currently on display at the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

WORLD

WAR I

At the start of World War I, Germany had twenty-nine U-boats; in the first ten weeks, five British cruisers had been lost to them. On 5 September 1914, HMS Pathfinder was sunk by SM U-21, the first ship to have been sunk by a submarine using a self-propelled torpedo. On 22 September, U-9 sank the obsolete British warships HMS Aboukir, HMS Cressy and HMS Hogue (the "Live Bait Squadron") in a single hour.

In the Gallipoli Campaign in the spring of 1915 in the eastern Mediterranean, German U-boats, notably the U-21, prevented close support of allied troops by 18 pre-Dreadnought battleships by sinking two of them.

For the first few months of the war, U-boat anti-commerce actions observed the "prize rules" of the time which governed the treatment of enemy civilian ships and their occupants. On 20 October 1914, SM U-17 sank the first merchant ship, the SS Glitra, off

Norway. Surface commerce raiders were proving to be ineffective, and on 4 February 1915, the Kaiser assented to the declaration of a war zone in the waters around the British Isles. This was cited as a retaliation for British

minefields and shipping blockades. Under the instructions given to U-boat captains, they could sink merchant ships, even potentially neutral ones, without warning. A statement by the U.S. Government, holding Germany "strictly accountable" for any loss of American lives, made no material

difference. In February 1915, a submarine was rammed and sunk off Beachy Head by the collier SS Thordis commanded by Captain John Bell RNR after firing a torpedo.

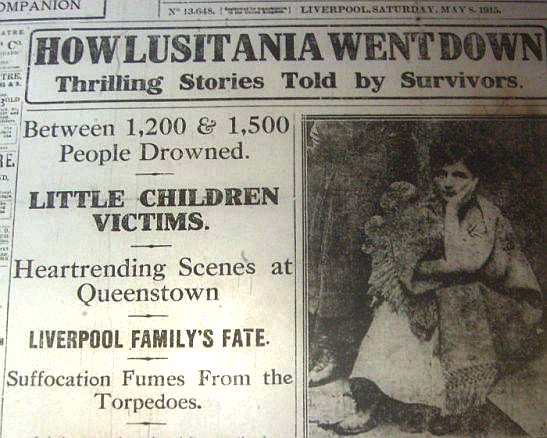

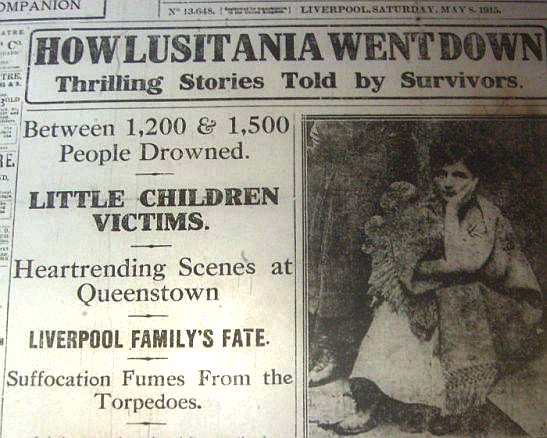

Liverpool

1915 newspaper report on the Sinking of the Lusitania

On 7 May 1915, SM

U-20 sank the liner RMS

Lusitania with a single torpedo hit, although it is debated whether a second explosion was due to flammable cargo or another torpedo. The sinking claimed 1,198 lives, 128 of them American civilians, including noted theatrical producer Charles Frohman and Alfred Vanderbilt, a member of the prestigious Vanderbilt family. The sinking deeply shocked the Allies and their sympathizers because an unarmed civilian merchant and passenger vessel was attacked. According to the ship's manifest, Lusitania was carrying military cargo. After further investigations, it has been confirmed that the Lusitania was in fact carrying ammunition for the allies to use against the Germans. However, this was not known at the time and the Lusitania was mistaken for a

troopship. It was not until the sinking of the ferry SS Sussex that there was a widespread reaction in the USA.

The initial U.S. response was to threaten to sever diplomatic ties, which persuaded the Germans to issue the Sussex pledge that re-imposed restrictions on U-boat activity. The U.S. reiterated its objections to German submarine warfare whenever U.S. civilians died as a result of German attacks, which prompted the Germans to fully re-apply prize rules. This, however, removed the effectiveness of the U-boat fleet, and the Germans consequently sought a decisive surface action, a strategy which culminated in the Battle of

Jutland.

Admiral

Karl Dönitz WWII

Although the Germans claimed victory at Jutland, the British Grand Fleet remained in control at sea. It was necessary to return to effective anti-commerce warfare by U-boats. Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, Commander in Chief of the High Seas Fleet, pressed for all-out U-boat war, convinced that a high rate of shipping losses would force Britain to seek an early peace before the United States could react effectively.

The renewed German campaign was effective, sinking 1.4 million tons of shipping between October 1916 and January 1917. Despite this, the political situation demanded even greater pressure, and on 31 January 1917, Germany announced that its U-boats would engage in unrestricted submarine warfare beginning 1 February. On 17 March,

German submarines sank three American merchant vessels, and the U.S. declared war on Germany in April 1917.

Unrestricted submarine warfare in the spring of 1917 was initially very successful, sinking a major part of Britain-bound shipping. Nevertheless with the introduction of escorted convoys shipping losses declined and in the end the German strategy failed to destroy sufficient Allied shipping. An armistice became effective on 11 November 1918 and all surviving German submarines were surrendered. Of the 360 submarines that had been built, 178 were lost but more than 11 million tons of shipping had been destroyed.

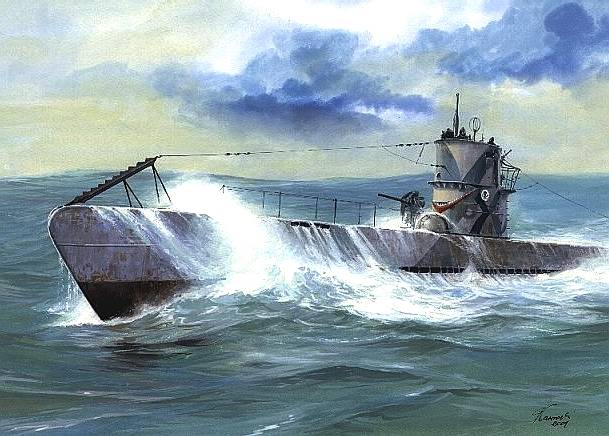

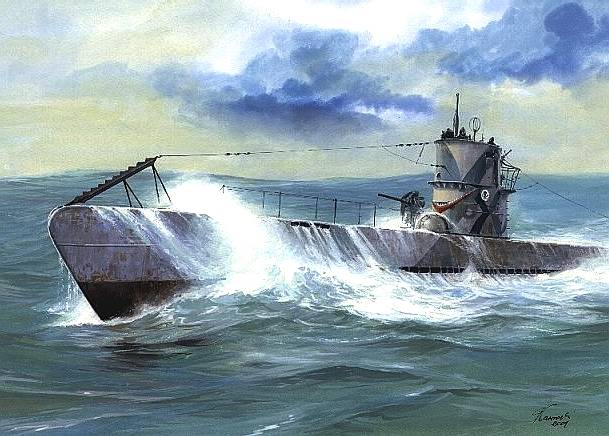

Second

World War U Boat art

U-BOAT

CLASSES

* Körting kerosene-powered boats

Type U 1, Type U 2, Type U 3, Type U 5, Type U 9, Type U 13, Type U 16, Type U 17

*

Mittel-U MAN diesel boats

Type U 19, Type U 23, Type U 27, Type U 31, Type U 43, Type U 51, Type U 57, Type U 63, Type U 66, Type Mittel U

*

U-Cruisers and Merchant U-boats

Type U 139, Type U 142, Type U 151, Type UD 1

*

UB coastal torpedo attack boats

Type UB I, Type UB II, Type UB III, Type UF, Type UG

*

UC coastal minelayers

Type UC I, Type UC II, Type UC III

*

UE ocean minelayers

Type UE I, Type UE II

SURRENDER OF THE FLEET

Under the terms of the Armistice, all U-boats were to immediately surrender. Those in home waters sailed to the British submarine base at Harwich. The entire process was done quickly and in the main without difficulty, after which the vessels were studied, scrapped, or given to Allied navies. Stephen King-Hall wrote a detailed eyewitness account of the surrender.

CALM

BEFORE THE STORM

At the end of World War I, as part of the Paris Peace Conference, 1919, the Treaty of Versailles restricted the total tonnage of the German surface fleet. The treaty also restricted the independent tonnage of ships and forbade the construction of submarines. However, a submarine design office was set up in the Netherlands and a torpedo research program was started in Sweden. Before the start of

World War

II, Nazi

Germany started building U-boats and training crews, labeling these activities as "research" or concealing them using other covers. When this became known, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement limited Germany to parity with Britain in submarines. When World War II started, Germany already had 65 U-boats, with 21 of those at sea, ready for war.

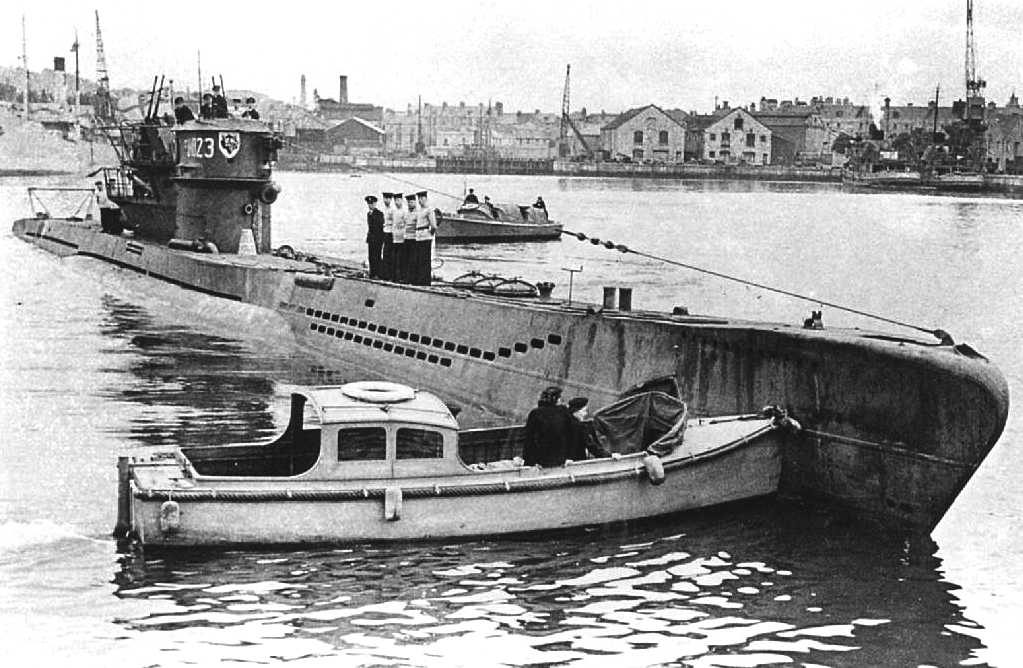

U-99 German submarine 1940 WWII

harbour maneuvers

WORLD

WAR II

During World War II, U-boat warfare was the major component of the Battle of the Atlantic, which lasted the duration of the war. Germany had the largest submarine fleet in World War II, since the Treaty of Versailles had limited the surface navy of Germany to six battleships (of less than 10,000 tons each), six cruisers and 12 destroyers.

It was an incredible loop-hole, but then there is always a loop-hole to

exploit.

Prime Minister

Winston Churchill wrote

on the menace:

"The only thing that really frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril."

In the early stages of the war, the U-boats were extremely effective in destroying Allied shipping, initially in the mid-Atlantic, where there was a large gap in air cover. There was an extensive trade in war supplies and food across the

Atlantic, which was critical for Britain's survival. This continuous action became known as the Battle of the Atlantic, as the British developed technical defences such as ASDIC and

radar, and the German U-boats responded by hunting in what were called "wolfpacks" where multiple submarines would stay close together, making it easier for them to sink a specific target. Later, when the USA entered the war, the U-boats ranged from the Atlantic coast of the United States and Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Arctic to the west and southern African coasts and even as far east as Penang. The U.S. military engaged in various tactics against German incursions in the Americas; these included military surveillance of foreign nations in Latin America, particularly in the Caribbean, in order to deter any local governments from supplying German U-boats.

Because speed and range were severely limited underwater while running on battery power, U-boats were required to spend most of their time surfaced running on

diesel

engines, diving only when attacked or for rare daytime torpedo strikes. The more ship-like hull design reflects the fact that these were primarily surface vessels which had the ability to submerge when necessary. This contrasts with the cylindrical profile of modern nuclear submarines, which are more hydrodynamic underwater (where they spend the majority of their time) but less stable on the surface. Indeed, while U-boats were faster on the surface than submerged, the opposite is generally true of modern subs. The most common U-boat attack during the early years of the war was conducted on the surface and at night, see submarine warfare. This period, before the Allied forces developed truly effective antisubmarine warfare (ASW) tactics, was referred to by German submariners as "die glückliche Zeit" or "the happy time."

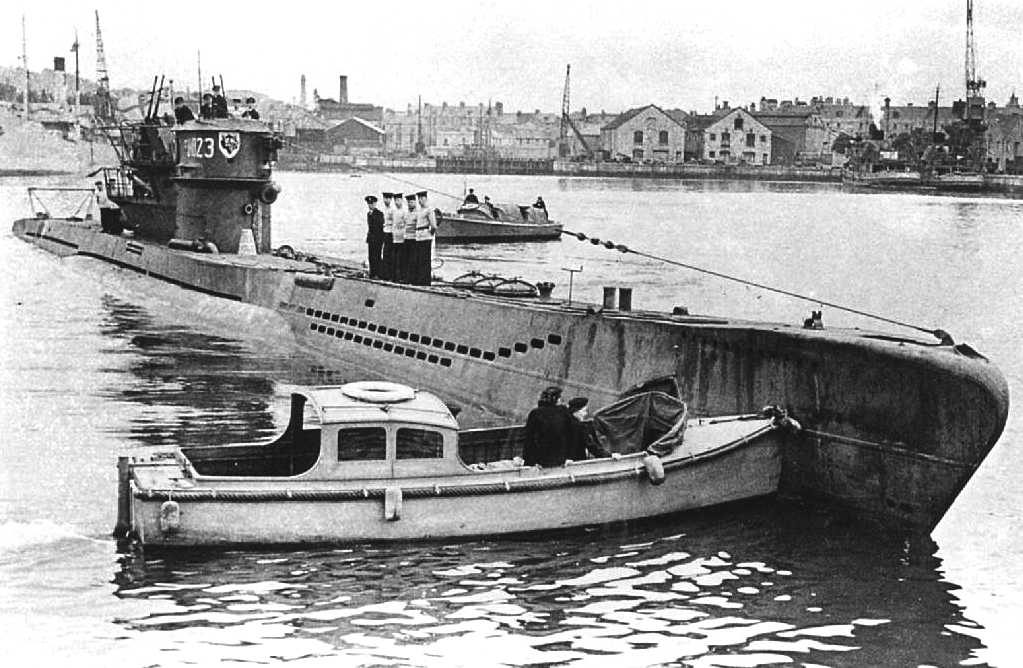

A

classic German WWII U boat ties up at

a mooring

U

BOAT ARMAMENTS

The U-boats' main weapon was the

torpedo, though mines and deck guns (while surfaced) were also used. By the end of the war, almost 3,000 Allied ships (175 warships; 2,825 merchant ships) were sunk by U-boat torpedoes. Early German World War II torpedoes were straight runners, as opposed to the homing and pattern-running torpedoes which were fielded later in the war. They were fitted with one of two types of pistol trigger: impact, which detonated the warhead upon contact with a solid object, and magnetic, which detonated upon sensing a change in the magnetic field within a few meters. One of the most effective uses of magnetic pistols would be to set the torpedo's depth to just beneath the keel of the target.

he explosion under the target's keel would create a shock wave, and the ship could break in two. In this way, even large or heavily armored ships could be sunk or disabled with a

single well-placed hit. In practice, however, the depth-keeping equipment and magnetic and contact exploders were notoriously unreliable in the first eight months of the war. Torpedoes would often run at an improper depth, detonate prematurely, or fail to explode altogether

- sometimes bouncing harmlessly off the hull of the target ship. This was most evident in Operation Weserübung, the invasion of Norway, where various skilled U-boat commanders failed to inflict damage on British transports and warships because of faulty torpedoes. The faults were largely due to a lack of testing. The magnetic detonator was sensitive to mechanical oscillations during the torpedo run and at high latitudes fluctuations in the Earth's magnetic field. These were eventually phased out, and the depth-keeping problem was solved by early 1942.

Later in the war, Germany developed an acoustic homing torpedo, the G7/T5. It was primarily designed to combat convoy escorts. The acoustic torpedo was designed to run straight to an arming distance of 400 meters and then turn toward the loudest noise detected. This sometimes ended up being the U-boat itself; at least two submarines may have been sunk by their own homing torpedoes. Additionally, it was found these torpedoes were only effective against ships moving at greater than 15 knots (28 km/h). At any rate, the Allies countered acoustic torpedoes with noisemaker decoys such as Foxer, FXR, CAT and Fanfare. The Germans, in-turn, countered this by introducing newer and upgraded versions of the acoustic torpedoes, like the late war G7es, and the T11 torpedo. However, the T11 torpedoes did not see active service.

U-boats also adopted several types of "pattern-running" torpedoes which ran straight out to a preset distance, then traveled in either a circular or ladder-like pattern. When fired at a convoy, this increased the probability of a hit if the weapon missed its primary target.

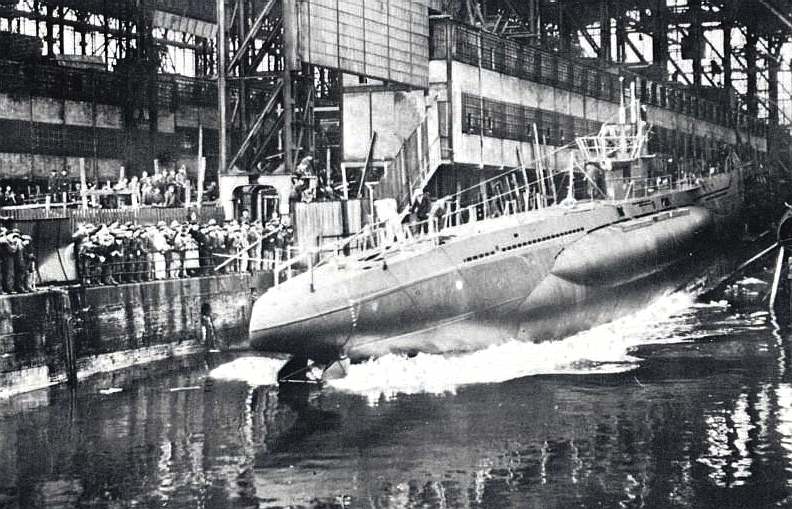

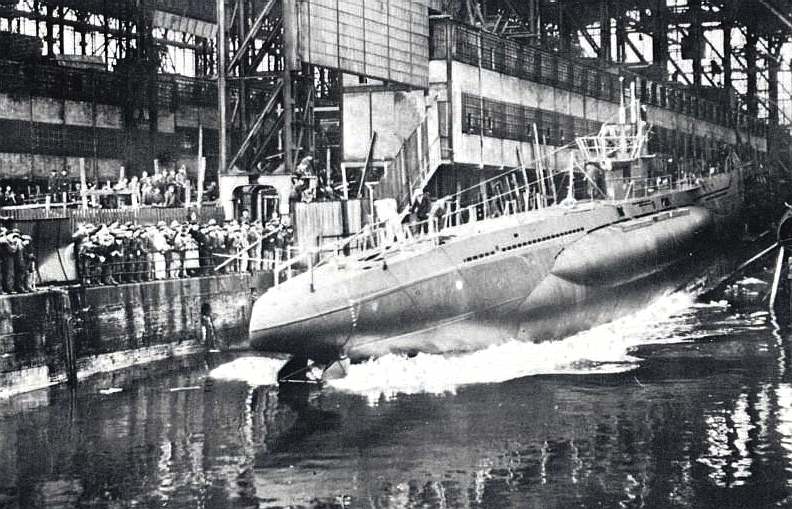

WWII

U Boat launch

U

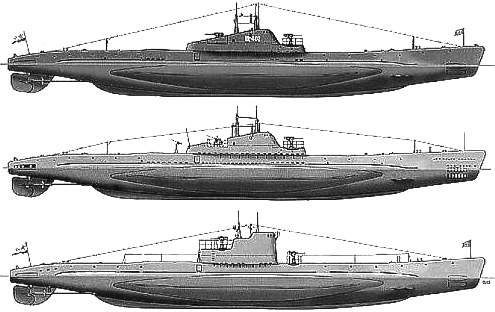

BOAT DEVELOPMENT

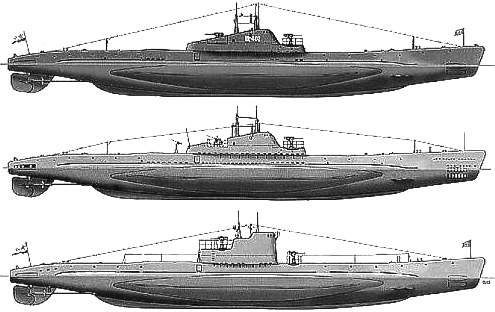

During

World War II, the Kriegsmarine produced many different types of U-boats as technology evolved. Most notable are Type VII, known as the "workhorse" of the fleet, which was by far the most-produced type; Type IX boats were larger and specifically designed for long-range patrols, some traveling as far as Japan and the east coast of the United States. With the Type XXI "Elektroboot", German designers realized the U-boat depended on submerged ability both for combat effectiveness and survival; this was the first submarine whose design favored submerged performance. The Type XXI featured a revolutionary streamlined hull design, which was the basis for the later

USS Nautilus nuclear submarine. Its propulsion system featured a large battery capacity, which allowed it to cruise submerged for long periods and reach unprecedented submerged speeds. A larger battery was possible because the space it occupied was originally intended to store

hydrogen peroxide for a Walter turbine, which was unsuccessful on the Type XVII.

Throughout the war an arms race evolved between the Allies and the Kriegsmarine, especially in detection and counter-detection. Sonar (ASDIC in Britain) allowed allied warships to detect submerged U-boats (and vice versa) beyond visual range but was not effective against a surfaced vessel; thus, early in the war, a U-boat at night or in bad weather was actually safer on the surface. Advancements in radar became particularly deadly for the U-boat crews, especially once aircraft-mounted units were developed. As a countermeasure, U-boats were fitted with radar warning receivers, to give them ample time to dive before the enemy closed in. However, at some point the Allies switched to centimetric radar (unbeknownst to Germany) which rendered the radar detectors ineffective. U-boat radar systems were also developed, but many captains chose not to utilize them for fear of broadcasting their position to enemy patrols.

The Germans took the idea of the Schnorchel (snorkel) from captured Dutch submarines, though they did not begin to implement it on their own boats until rather late in the war. The Schnorchel was a retractable pipe which supplied air to the

diesel engines while submerged at periscope depth, allowing the boats to cruise and recharge their batteries while maintaining a degree of stealth. It was far from a perfect solution, however. There were problems with the device's valve sticking shut or closing as it dunked in rough weather; since the system used the entire pressure hull as a buffer, the diesels would instantaneously suck huge volumes of air from the boat's compartments, and the crew often suffered painful ear injuries. Waste disposal was a problem when the U-boats spent extended periods without surfacing. Speed was limited to 8 knots (15 km/h), lest the device snap from stress. The schnorchel also had the effect of making the boat essentially noisy and deaf in sonar terms. Finally, Allied

radar eventually became sufficiently advanced that the schnorchel mast itself could be detected beyond visual range.

The later U-boats were covered in a sound-absorbent rubber coating to make them less of an ASDIC target. They also had the facility to release a chemical bubble-making decoy, known as Bold, after the mythical kobold.

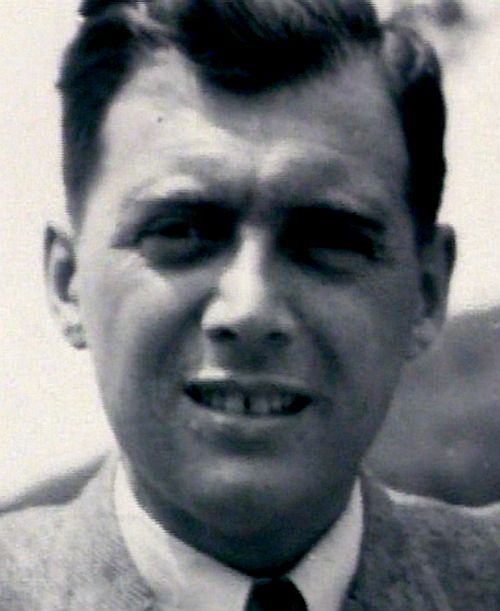

U-Boat 156 Captain Werner Hartenstien,

WW2 Hero with a conscience

U

BOAT HEROES

The

Laconia plied through the Atlantic, Captain Rudolph Sharp

at the helm enjoyed the sun set over the western horizon, knowing the beneath the waves,

deadly killers were prowling for allied targets.

The Cunard liner was once a luxury ship, hastily converted to a troopship.

Now the passengers were 2,700 people, mostly Italian prisoners of war guarded by Polish troops, along with dozens of injured British soldiers and other military personnel and 87 women and children — mainly families of servicemen.

The Laconia was on its way from Egypt to Britain navigating around the

Cape of Good Hope because the Mediterranean was too dangerous, being

controlled by the Axis powers. The ship reached Cape Town in September 1942 before sailing up the West African coast.

By September 12, the Laconia was roughly 900 miles south of Freetown, the British naval port in Sierra Leone, and 250 miles north-east of Ascension Island.

The liner was now rather shabby and in need of maintenance. Its hull was festooned in barnacles that slowed it down, and its funnel belched black smoke which was visible for miles.

Captain Sharp was painfully aware that his vessel, sailing without a convoy and with only a few guns, was

vulnerable to a U-boat attack. But many of the passengers, relieved to be going home, had begun to relax, despite the regular lifeboat drills.

In the cabin she shared with her parents and ten-year-old brother, Alec, 14-year-old Josephine Frame was climbing onto the top bunk as her parents were leaving the cabin to go to a dance in the ballroom upstairs.

Suddenly there was, she remembers, ‘a horrendous noise. Then a deathly silence’. The ship rocked violently. Then another terrible explosion and the ship began listing to its starboard side.

The Laconia had been struck by two torpedoes, one at 8.07pm, the other 30 seconds later. They had been fired by a German submarine, U-156, part of a U-boat wolf pack hunting for Allied ships.

Hitler was determined to prevent the build-up of men and munitions in Britain that would enable the Allies to invade Occupied Europe. His U-boat captains had orders to sink any ships carrying troops or armaments.

Captain Werner Hartenstein of U-156 had sighted the Laconia earlier that day. A U-boat ace, he had already sunk just short of 100,000 tonnes of Allied shipping during the war. By sinking the 20,000-tonne Laconia, he would reach that total, making him eligible for the German military award, the Ritterkreuz.

But the events of the coming days were to prove that Captain Hartenstein was far from a ruthless Nazi killing machine. Indeed, in one of the most extraordinary episodes of World War II, he was about to emerge as a very unlikely hero.

The story of the Laconia incident, as it became known, has been made into a drama, as well as a documentary, to be shown on BBC2 for the next three nights. It portrays some German submariners, not as the callous monsters of British wartime propaganda, but as courageous, humane men whose behaviour contrasted starkly with that of some of our allies.

For the remaining survivors of that terrible night, the events remain painfully clear nearly 70 years on.

Josephine Frame (now Pratchett, a retired teacher living in Northamptonshire), recalls the panic when the ship was hit.

‘It was carnage. People were screaming, there were bodies everywhere. The ship was listing so badly they could not get the lifeboats clear of the side at first.’

Josephine watched in horror as another family tried to get into another lifeboat with their three young sons.

‘As Mrs Lindsay put the baby into the boat, it tipped over. The baby fell into the sea and was drowned. Mrs Lindsay was screaming, it was terrible.’

Women and children were given priority in the lifeboats. Many of the men jumped off the side of the ship, some injuring themselves badly.

Down in the hold, where the two torpedoes had struck, hundreds of Italian PoWs were killed instantly. Others struggled to escape as water poured in. As they came on deck, Polish and British soldiers held them back from the lifeboats at bayonet point.

Doris Hawkins, a nursing sister, had been looking after a 14-month-old baby girl for her parents. She finally found a place in the lifeboat only for it to capsize just as the baby was handed to her.

‘I lost her,’ Doris wrote afterwards. ‘I did not hear her cry even then, and I am sure that God took her immediately to Himself without suffering. I never saw her again.’

Some of the lifeboats were launched in such haste that the bungs for the drain holes had not been inserted, so they filled with water and sank.

The ship’s officers left the Laconia last. Those who survived the leap into the sea clung to debris, and watched the Laconia’s stern rear out of the water before she sank below the waves with a hiss and a roar. Captain Sharp went down with his ship.

Next came another terrifying explosion as the Laconia’s boilers burst, covering the sea, and everyone in it, with oil.

Soon, ominous black shapes began to join the survivors in the water, attracted by the smell of blood: screams rent the air as

sharks and barracuda began to attack the living and dead.

Then, came the unmistakable rumble of a U-boat’s engine - terrifying for those still clinging to life, as Allied propaganda had depicted U-boat commanders as

Nazi fanatics who would machine-gun survivors in the

water.

Cunard's liner Larconia at Southampton docks in 1922

Adolf

Hitler himself had decreed: ‘Since foreign seamen cannot be taken prisoner

the U-boats are to surface after torpedoing and shoot up the lifeboats.’

Instead, the Laconia survivors’ fear turned to amazement as they saw the Germans on the U-boat’s deck begin dragging victims from the water.

Hearing the cries of the Italians, Hartenstein assumed he had just torpedoed a ship full of Germany’s allies — then he saw with horror that women and children were among the survivors. So he decided to rescue everyone, regardless of nationality.

Soon the entire deck of the submarine was crowded with men, women and children.

They were taken below, given dry clothes, warm tea and bread. To ease the overcrowding on the tiny submarine, the unharmed men were put back into the

lifeboats, which were then tied together or lashed to the U-boat with lifelines.

All that night and the following day, Hartenstein’s men worked tirelessly, pulling people from the sea and shepherding the flotilla of lifeboats and rafts.

Doris Hawkins had endured a terrible 24 hours since the Laconia had sunk. After losing the baby, Sally, she had been hauled aboard a life raft to which she, along with nine men, clung all night — shivering with cold.

The following day, they had drifted beneath the fierce tropical sun, their skin blistering painfully, their limbs swollen by saltwater and their throats burning with thirst. By the time they were spotted by the U-boat that evening, one man had already died.

They were taken on board and treated with ‘great kindness and respect’, the German officers giving up their bunks to the exhausted survivors.

To her joy, she found on board a friend she had made on the Laconia, Mary, the wife of an Army officer based in Egypt, who was going home to see her two young sons. What Doris did not know was that Mary was pregnant with another child, by her lover, a Fleet Air Arm lieutenant, Peter Medhurst, also travelling on the ship.

Onboard U-156, there were now 193 survivors and a further 200 in the lifeboats that clung to it.

Approximately 1,100 other survivors floated in lifeboats nearby.

Hartenstein had radioed U-boat command, shortly after picking up the first survivors, informing them of the presence of the Italian PoWs and asking for instructions.

Admiral Donitz, head of the German U-boat fleet, ordered two other submarines in the area to assist the rescue and the Italian navy sent its nearest submarine. Vichy France — ostensibly neutral but largely pro-Axis — also sent three ships from a naval base in North Africa.

But Hartenstein knew that Allied shipping, or planes, might sight his U-boat and attack it, unaware of who was on board. He needed the survivors to be rescued.

He therefore took an unprecedented step. Using an open radio frequency he broadcast a message in English: ‘If any ship will assist the wrecked Laconia crew, I will not attack her, provided I am not attacked by ship or aircraft. I have picked up 193 men.’

He then gave his co-ordinates, signing off: ‘German submarine.’

If any British listening stations in Africa picked up this offer of ceasefire, there is no record of it. It is possible that it was heard, but dismissed as a trick.

If it was intercepted, then no one thought to pass it on to Ascension Island 250 miles away, the site of a secret American airfield where planes could refuel mid-Atlantic.

The Americans were merely told that the Laconia had sunk and that two British ships were being sent to look for survivors. They were requested to provide air cover, but no mention was made of Hartenstein’s rescue or his ceasefire offer. So American planes began combing the Atlantic for U-boats, primed to attack them.

Meanwhile, the rescue continued. Josephine Frame and her family had been floating in a lifeboat awash with blood and vomit for four appalling days, surrounded by dead bodies and

sharks, before the U-156 found them.

They staggered on board, stupefied with exhaustion and sunburn. But their salvation was all too brief.

On Wednesday, September 16, Captain Hartenstein saw an American B-24 bomber approaching. Assuming the plane was part of a rescue effort, his crew spread out a large

Red Cross flag on the deck, and signalled their peaceful intentions with lamp and morse code.

Unfortunately, the pilot, Lieutenant James Harden, didn’t understand the signals. He radioed back to Ascension Island to report what he had seen and ask for orders.

Airfield commander Captain Robert Richardson deliberated. Though the ship was flying a Red Cross flag, it was an enemy submarine and therefore a danger both to the airfield and to Allied shipping. He gave the order: ‘Sink the sub.’

Back on the U-156 passengers and crew watched the bomber curiously, then with horror as the bomb doors opened and two bombs were released. They both missed, but Harden returned for a second and then a third attempt. Several lifeboats were hit, killing dozens. The U-boat was slightly damaged.

Hartenstein had no choice but to save his submarine, so he ordered the 93 Laconia survivors overboard. They jumped into the

shark-infested waters and swam for the remaining lifeboats as U-156 headed away from the danger zone.

U Boat

156 rescues passengers from the Larconia

Fortunately, just hours later the Vichy French ships arrived and picked up most of the survivors and took them to Dakar, West Africa, from where they were sent to internment camps.

Josephine Frame and her family ended up in an internment camp near Casablanca: ‘It was pretty awful; dysentery was rife. But it was wonderful to be back on dry land.’

They were liberated by Allied forces several weeks later. But in the confusion, the French ships had missed two of the lifeboats. Lifeboat 9, with 68 people on board including Doris Hawkins, Mary and Peter Medhurst, was left to row for the African coast, 600 miles away.

By the time it reached land 27 days, later, 16 people had died, including Mary and her lover Peter, who, after she passed away, slipped overboard into the sea. The other lifeboat was discovered by a British trawler after 40 days at sea. Only four of its 52 occupants were alive.

Altogether, of the 2,725 passengers that had embarked from Cape Town, only 1,500 had survived the tragedy.

The repercussions of the Laconia incident were far-reaching. On September 17, the day after the bombing of U-156, Admiral Donitz sent a message to all U-boat commanders that became known as the Laconia Order, forbidding any attempt to help survivors of sunken ships.

After the war, many Laconia survivors remained bitterly angry towards Captain Richardson, believing the bombing of U-156 was a criminal act. But he was never prosecuted, and went on to serve a long career in the U.S. Air Force. He died, aged

92 in 2011.

Werner Hartenstein, the hero of the Laconia incident, died with his men when his U-156 was sunk by a U.S. bomber in the Atlantic in March 1943.

Laconia survivors were saddened to learn of his death. ‘He was a good man,’ says

Josephine Pratchett. ‘He was doing his job torpedoing our ship, but by rescuing us he showed great courage and humanity.’

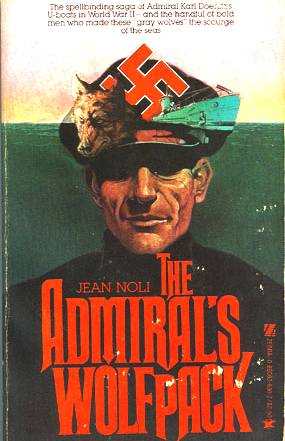

Dozens

of books have been written about U Boat wolf pack tactics

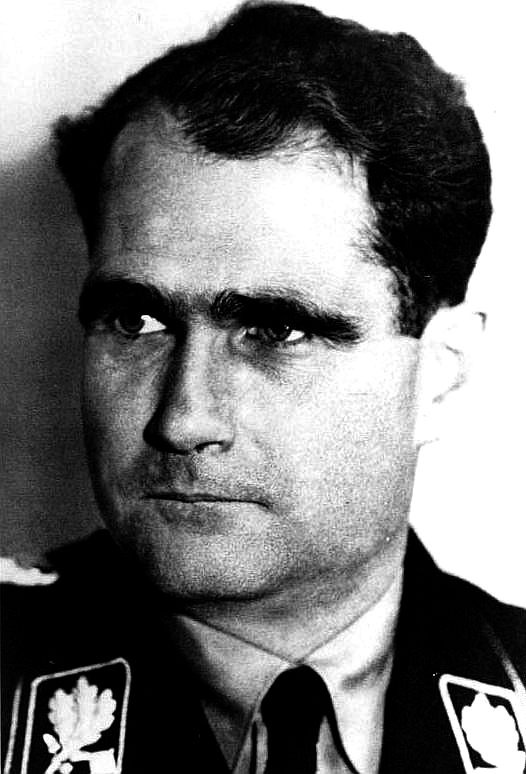

WHO

WE WERE FIGHTING AGAINST FROM 1939 TO 1945

|

Adolf

Hitler

German

Chancellor

|

Herman

Goring

Reichsmarschall

|

Heinrich

Himmler

Reichsführer

|

Joseph

Goebbels

Reich

Minister

|

Philipp

Bouhler SS

NSDAP

Aktion T4

|

Dr

Josef Mengele

Physician

Auschwitz

|

|

Martin

Borman

Schutzstaffel

|

Adolph

Eichmann

Holocaust

Architect

|

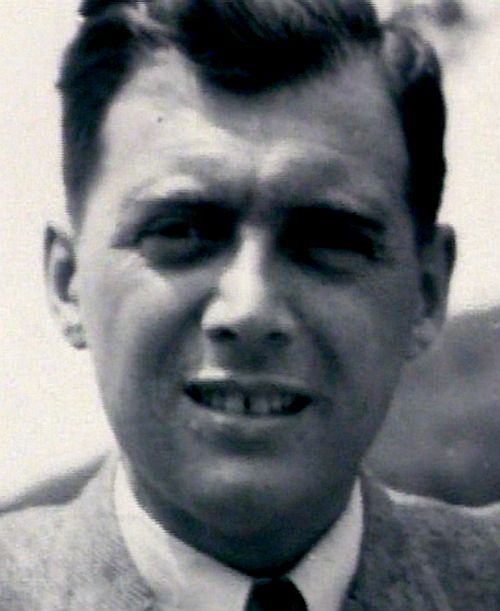

Rudolf

Hess

Commandant

|

Erwin

Rommel

The

Desert Fox

|

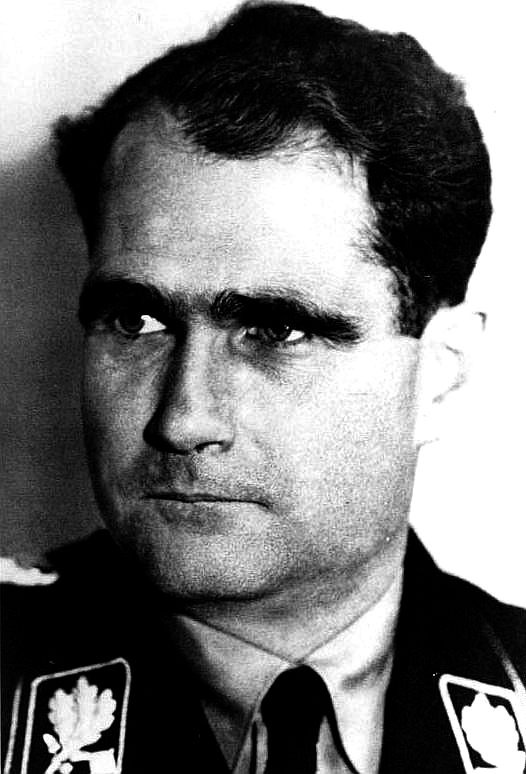

Karl

Donitz

Kriegsmarine

|

Albert

Speer

Nazi

Architect

|

WOLF

PACKS

The term

'wolfpack' refers to the mass-attack tactics against convoys used by German U-boats of the Kriegsmarine during the Battle of the Atlantic

in World War II.

Karl Dönitz used the term Rudeltaktik to describe his strategy of submarine

warfare - Rudeltaktik translates best as "tactics" of a "pack" of animals and has become known in English as

"wolfpack" (Wolfsrudel), a more accurate metaphoric, but not literal, translation.

U-boat movements were controlled by the Befehlshaber der Unterseeboote

(BdU; English translation: "Commander of Submarines") much more closely than American submarines, which were given tremendous independence once on patrol. Accordingly, U-boats usually patrolled separately, often strung out in

co-ordinated lines across likely convoy routes (usually merchants and small vulnerable destroyers), only being ordered to congregate after one located a convoy and alerted the

BdU, so a Rudel consisted of as many U-boats as could reach the scene of the attack. With the exception of the orders given by the

BdU, U-Boat commanders could attack as they saw fit. Often the U-Boat commanders were given a probable number of U-Boats that would show up, and then when they were in contact with the convoy, make call signs to see how many had arrived. If their number were sufficiently high compared to the expected threat of the escorts, they would attack.

Although the wolfpacks proved a serious threat to Allied shipping, the Allies developed countermeasures to turn the U-boat organization against itself. Most notably was the fact that wolfpacks required extensive radio communication to coordinate the attacks. This left the U-boats vulnerable to a device called the High Frequency Direction Finder

(HF/DF or "Huff-Duff") which allowed Allied naval forces to determine the location of the enemy boats transmitting and attack them. Also, effective air cover, both long-range planes with

radar, and escort carriers and blimps, allowed U-boats to be spotted as they shadowed a convoy (waiting for the cover of night to attack). The destroyers of the Atlantic also used depth charges and other small mines which could be dropped off the ships' side.

German U Boat on display at

Birkenhead docks

WWII

U BOAT CLASSES

Type I

Type II

Type V

Type VII - Known as the 'workhorse' of the U-boats, with 700 active in WW2

Type IX - These ocean-going U-boats operated as far as the Indian Ocean with the Japanese

(Monsun

Gruppe), and the South Atlantic.

Type X

Type XI

Type XIV - Used to re-supply other U-boats; nicknamed the Milk Cow

Type XVII

Type XXI - Known as the Elektroboot.

Type XXIII

Midget submarines, including Biber, Hai, Molch, Seehund.

A

computer game that simulates U Boat war in the Atlantic

MODERN U-BOATS

The advent of the nuclear submarine in the 1950s brought about a major change in submarine warfare.

Modern undersea boats are faster, dive deeper and have much longer endurance.

Their new size means they've become missile launching platforms. There have also been major advances in sensors and weapons.

In today's more fractured geopolitical system, many nations are building and/or upgrading their submarines. The JMSDF has launched new models of submarines every few years; South Korea has upgraded the already capable Type 209 design from Germany and sold copies to Indonesia. Russia has improved the old Soviet Kilo model into what many are calling equivalent to the 1980s-era 688-class, and so on.

At the moment

submarines are the only naval units capable of evading

conventional intelligence capabilities (space satellites, airplanes etc.) that a fight between evenly matched modern states could bring to bear on them.

The whole point of development is to create a mis-match in technology, to

maintain an edge. It is thought that the future of anti submarine warfare is persistent monitoring

with the latest detection equipment. Perhaps the future for the safety of our

oceans are ZCCs

equipped with torpedoes or other weapons

capable of sinking a submarine.

Hasting

beach in Sussex, England - U-Boat 118 in 1919

SUBMARINE

INDEX

Alvin

DSV - Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Deepsea

Challenger - Mariana Trench, James Cameron 2012

HMS

Astute 1st of Class

BAE Systems

HMS

Vanguard- Trident

INS

Sindhurakshak - explosion

& sinking

Littoral

combat vessels

Lusitania

- Torpedo

attack

Nuclear

submarines lost

at sea

Predator

- Covert submarine hunter/killer

Sealab

- US Navy underwater research laboratory

Seaview

- Voyage to the bottom of the sea

Seawolf

- Autonomous wolf pack deployment of Predator mini-subs

Torpedoes

- UUV anti submarine weapons

Trieste

- World record depth - Mariana Trench 1960

U20

- Kapitan Leutnant Walther Schwieger

USS

Alabama -

USS

Bluefish WWI submarine

USS

Bluefish - Nuclear submarine

USS

Flying Fish

USS

Jimmy Carter - Seawolf class fast attack nuclear submarine

USS

Nautilus - 1st nuclear submarine & subsea north pole passage

USS

North Dakota - 11th Virginia class submarine

USS

Scorpion - Lost at sea with all hands

SUBMARINE

HKs - If the submerged nuclear submarine

shown above has a crew on board (most

likely) they are in grave danger, because the ASV submarine hunter-killer (HK)

on the surface above it is a drone that can either track the

submarine and pass information to

a network of marine drones like itself, cruising as a fleet - such as to keep it on a database, or, in times of hostilities -

sink the submarine

as soon as it is located with torpedoes or depth

charges using the SeaNet or similar battleship combat systems.

The US Navy tested a very basic version of this concept in Singapore in

November 2013 when searching for a Chinese nuclear submarine, by linking

underwater hydrophones to modern US Navy submersibles. From the 1950s, the U.S. listened for Soviet subs entering the

Atlantic and Pacific oceans by stringing underwater microphones across the seabed around its coast and in strategic chokepoints, such as between the U.K. and Iceland.

The SkyNet system takes things to a new level, that no Navy in the world

is developing at the moment, through lack of vision maybe, even though the

likes of DARPA

and the DSTL

exist for this exact purpose.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

U-boat-skipper-ruthlessly-torpedoed-British-ship-defied-Hitler-rescue-survivors

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/612159/U-boat

Solved-Mystery-missing-WW1-German-submarines-uncovered-explorers-remains-41-U-boats-UK-coast

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/u-boats.htm

Uboat

- U-boat

archive

Marine

Technology News U-Boat wrecks found North Carolina

http://www.marinetechnologynews.com/news/wrecks-found-north-carolina-502439

http://www.submerged.co.uk/u534.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/U-boat

http://www.uboatarchive.net/

http://www.uboat.net/

http://www.navy.mil/

http://www.lusitania.net/lastrestingplace.htm

http://www.history.navy.mil/wars/korea/minewar.htm

hhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMHS_Britannic

hhttp://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMHS_Britannic

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Admiralty_Mining_Establishment

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_mine

http://www.enterprise-europe-scotland.com/sct/news/?newsid=4306

German U Boat

995 and service medal below

|