|

SUPERB

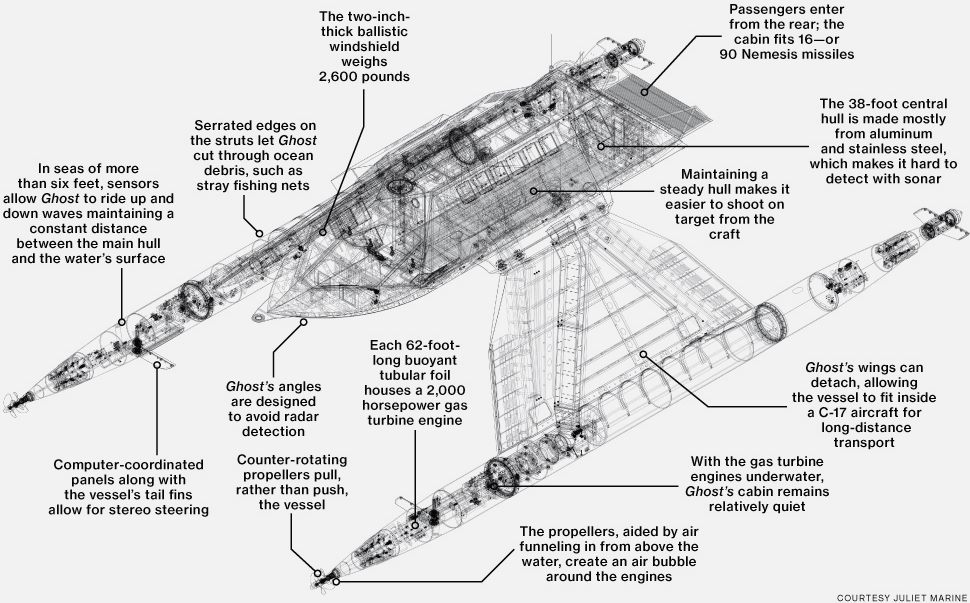

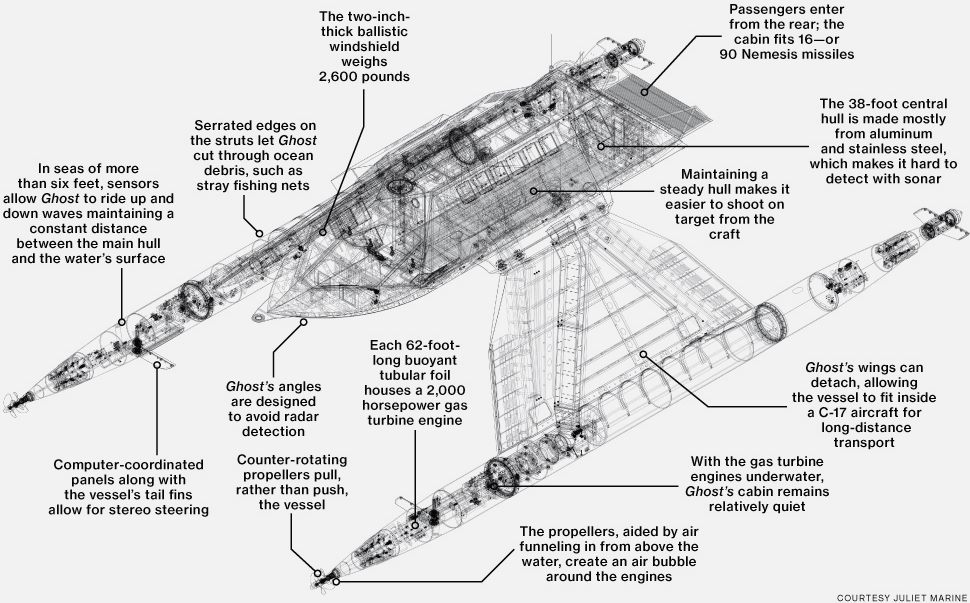

DESIGN - The Ghost uses a dual-pontoon supercavitating hull, known as the small

waterplane-area twin-hull (SWATH), to run at top speed through 10 ft (3.0 m) seas. It is gyro-stabilized, control is provided by 22 underwater control surfaces. Below eight knots, the Ghost sits in the water on its centerline 38 ft (12 m)-long module; faster than this, the marine aluminum buoyant hulls lifts the main hull out of the water by two 12 ft (3.7 m)-long struts, achieving full stability and reducing the amount of area resisting the water. Each strut is attached to a 62 ft (19 m)-long underwater tube that contains the engines. Four propellers are at the front of the tubes, which is more stable and allows for better control at high speeds; the propellers funnel air down through the struts, creating a gas bubble around each tube (the cavitation effect) for reduced drag and smooth motion. Propulsion on the prototype is provided by two T53-703 turboshaft engines providing 2,000 horsepower, there are plans to later adopt the General Electric T700 turboshaft engine. Since the tubes that contain the engines, fuel, and most computing systems are underwater, this lessens vulnerability because critical systems are protected by the water itself. The aircraft-style cockpit is outfitted with large windshields fashioned from two inch-thick glass; steering is provided via a throttle and joystick arrangement. The Ghost has achieved speeds of over 30 knots, and is being tested to 50 knots.

DECEMBER

15 - JULIET MARINE

- SWATH GETS SMARTER

US-based marine technology company Juliet Marine Systems, claims it has solved the technical challenge of controlling small waterplane area twin hull (SWATH) vessels at high speed.

The company says its Ghost demonstration vessel has shown the ability to safely and smoothly transport personnel and payloads through heavy seas at over 30 knots. These capabilities protect personnel and improve their ability to function in challenging missions. With Ghost, JMS says it will raise the bar for patrol boat capability.

JMS says it has ‘perfected patented SWATH control and is refining active drag reduction technologies that independent expert studies have shown will increase performance significantly in next generation offerings’.

The submerged, torpedo-shaped twin hulls appear to use traction propellers at their forward bows. The engines also exhaust their spent gasses somewhere behind these

propellers so that the submerged hulls are largely running in a mass of bubbles to reduce drag.

An additional development that this vessel displays is that the angle at which the twin hulls are supported is adjustable by a

hydraulic system. This means the vessel’s main hull can be carried high to better clear waves or the vessel can be hunkered down closer to the

water with its cat hulls far apart for maximum stability.

JMS technology may be suitable for applications in defence, commercial and recreational applications and in surface and subsea, manned and unmanned systems.

JULIET

CORE TECHNOLOGY

Juliet Marine Systems is a marine technology company dedicated to advancing high performance watercraft. We develop and commercialize innovative marine technologies to rapidly deliver new products and capabilities to defense and commercial markets.

JMS has developed intellectual property specific to the field of high speed small waterplane area twin hull (SWATH) vessels. We have solved the problem of controlling

SWATH vessels at speed beyond 30 knots while delivering a smooth and safe ride. We have demonstrated drag reduction techniques that allow us to achieve 5 to 10% improvement in speed without added fuel or power, and without moving parts.

APPOINTMENT

- May 12, 2015 - PORTSMOUTH, N.H., Juliet Marine Systems was pleased to announce that Justin Manley

joined the company as Vice President of Business Development and Marketing. Mr. Manley brings over 20 years of experience in the marine technology sector including roles at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA). He has also led growth of sales and development of new products at both startup companies and public corporations. At JMS Mr. Manley will lead all aspects of sales, marketing and business development.

Greg Sancoff President and CEO of JMS is quoted as saying: "We are thrilled to welcome Justin to our team,"

"He will have a tremendous impact as we grow our international defense sales and explore commercial market opportunities."

In addition to his new role at JMS Mr. Manley is extensively involved in the marine technology profession through a variety of leadership roles. He is a Senior Member of IEEE, Vice President of Government and Public Affairs for the Marine Technology Society and a member of the U.S. Integrated Ocean Observing Systems.

JULIET

HISTORY

Inventor Gregory Sancoff had decided to focus on small watercraft following the attack on the USS Cole in 2000, after which he recalled saying: "Some yahoo terrorists in a cheap little boat and $500 worth of explosives can kill 17 sailors on a

billion-dollar ship?" He also came across a 630-page

U.S. Navy report on an exercise called Juliet, where the Navy attacked an enemy force of small, high-speed boats; after two days, the Navy had suffered over 20,000 simulated casualties. Sancoff gathered information on marine technology, including hydroplane racing boats and high-speed supercavitating

torpedoes.

In 2007, Sancoff founded Juliet Marine Systems, named after the Navy exercise that inspired him, and began work on a plywood hull mock-up at Portsmouth, N.H.. In October 2009, Sancoff's patent attorney received a letter from the U.S.

Patent and Trademark Office, with a recommendation from the Office of Naval Research (ONR), enforcing a secrecy order forbidding Juliet Marine from filing its patents internationally or speaking about its technology; the secrecy orders were lifted in 2011. Prototype trial runs were conducted at night; the main hull section failed to lift out of the water on its first dozen runs, it first successfully lifted in 2011, reaching roughly 4 ft (1.2 m) high. Trials revealed the vessel's smoothness, traversing 8–10 ft (2.4–3.0 m) high waves without the crew feeling much seasickness, unlike those onboard an accompanying chase boat.

In 2014, Sancoff declared he was "aware" of the Department of Defense's apprehension to working with startup companies. The Navy has a policy of only buying technologies of an announced interest and cannot procure a system without established requirements. In 2009, the

Defense Advanced Projects Research Agency (DARPA) expressed interest in funding the Ghost, Sancoff rejected this to retain the patent rights. The ONR reportedly produced feedback declaring a lack of trust in the design. He also voiced concerns over potential theft of the design as the patents are

publicly available, and repeated attempted to breach the company's computer systems. U.S. allies have expressed interest in the Ghost, and Sancoff has said he is willing to make a foreign sale. In September 2014, the State Department permitted Foreign Military Sales discussions with

South Korea about the Ghost.

In 2014, it was reportedly offered to several nations including Bahrain, Qatar, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Japan,

Taiwan, South Korea, and

Singapore. High-level discussions were allegedly held with one nation interested in 25 Ghosts in a potential $300 million sale. Juliet Marine also offered a scaled-up corvette-sized Ghost 150 ft (46 m) in length during the U.S. Navy's re-evaluation of the Littoral Combat Ship program; costing about $50 million per vessel, it is six times cheaper than the $300 million per-ship cost of a Freedom-class and Independence-class littoral combat ship. One impediment to U.S. Navy procurement of the Ghost is a preference of senior leaders for large-hulled

ocean-going vessels that can also perform inshore operations instead of smaller craft specialized for inshore missions.

You

can lead a horse

to water, but you cannot make it drink. Funny though how $billions go to favored

contractors for projects that do not advance ship technology - just keep a

workforce on standby, but nothing goes to truly innovative SMEs, those who

really need the development tickover. It is always the way with big

business and disruptive technology. Navies should realize that peace

depends on maintaining the technology lead. Hang in their Juliet.

JULIET

MARINE CONTACTS

+1

603-319-8412

62 Deer St, Portsmouth, NH 03801,

USA

http://www.julietmarine.com/

Email:

Info@julietmarine.com

BLOOMBERG

21 AUGUST 2014 - STEALTH BOAT TOO INNOVATIVE FOR PENTAGON

On the northern edge of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Maine, past the security checkpoint and high-tech stations for refurbishing nuclear submarines, is a derelict warehouse that once doubled as a sawmill. Building 129’s corrugated metal exterior is rusted and overgrown with bursts of ivy. Broken glass in some of the windows has been replaced with clear plastic. Inside, it takes a moment to adjust to the cavernous silence and dim orange lighting, but one immediately senses the hulking presence of the hangar’s inhabitant: a vessel called Ghost.

Matte gray, with the chiseled angles of a Nighthawk stealth aircraft, Ghost doesn’t look like a boat. Its 38-foot main hull is designed to travel above the water’s surface, propped up by two narrow struts, both 12 feet long and razor-sharp at the front so they can cut through ocean debris. Underwater, each strut is attached to a 62-foot-long tube that contains a gas turbine engine. Hinges allow the struts to move up and down like wings. While parked, or traveling through shallow waters, they can be extended to the side. In deeper waters, at speeds of eight knots or higher, they can rotate downward to lift the hull into the air, eliminating the jarring impact of waves.

Four propellers positioned at the front of the tubes are powered by the two 2,000-horsepower engines. They pull the craft and, with the help of air funneling down through the struts, create a gas bubble around each

tube - an effect known as supercavitation that can reduce drag by a factor of 900. In short, Ghost makes a bubble and flies through it.

“It’s such a smooth ride, you can sit there and drink your coffee going through six-foot swells,” says Gregory Sancoff on a recent trip to the hangar. A self-made millionaire who started a string of medical technology companies, he’s looking up at Ghost, grinning. This is his baby. Sancoff came up with its design, leased the ramshackle hangar, and built the vessel entirely on spec. His 18-person startup, Juliet Marine Systems, has invested $15 million in the project.

Ghost, Sancoff says, could be used as a kind of “attack helicopter of the

sea” - conducting coastal defense and anti-terrorism missions and protecting massive naval vessels from swarm attacks by armed speedboats. Built from

aluminum and stainless

steel, the vessel is nonmagnetic and difficult to target using sonar. “We came up with the name Ghost because the boat is intended to have no radar signature at all,” says Sancoff. “With Ghost, you can get into denied-access ocean areas and loiter for 30 days with the fuel on board. You can listen to cell phone conversations, you can monitor what’s going on, you can launch operations and leave, and no one knows you’re there.” He adds, “That’s not something the government can do right now.”

HOW

THE GHOST WORKS - The 38-foot long main cabin rests on top of a pair of 12-foot tall struts which, when moving at speed, prop the cabin above the water like a hydrofoil.

The struts swivel at their base, allowing them to be raised and lowered depending on the water depth.

While parked, or traveling through shallow waters, they can be extended to the side.

In deeper waters, at speeds of eight knots or higher, they can rotate downward to lift the hull into the air, eliminating the jarring impact of waves.

They're sharpened along the leading edge as well to slice through submerged debris.

At the other end of each strut, a 62-foot long tube houses a 2,000HP gas turbine engine spinning two front-mounted propellers.

These tubes also eject a pocket of air from the front to generate a supercavitation effect that reduces the ship's drag coefficient by a factor of 900.

Juliet Marine’s board includes an impressive roster of what Sancoff calls “type A personalities.” These include former New Hampshire Senator John Sununu Jr., recently retired four-star Admiral James Hogg, and retired Rear Admiral Jay Cohen, who served as Defense’s chief of naval research and under secretary for science and technology at the Department of Homeland Security. Also on board is Rear Admiral Thomas Richards, a grandfatherly retired commander of special warfare who oversaw all of the country’s

Navy SEALs. “We expect to be breaking the speed record for SWATHs

- Small Waterplane Area Twin Hulls—by the end of the season,” says Richards. “The Navy has nothing like this.”

With Juliet Marine nearly ready to launch speed tests and build additional, refined models, Sancoff hopes the Department of Defense will sign on and buy his boats for roughly $10 million apiece. Top government officials, including Admiral Michelle Howard, vice chief of naval operations, who led the 2009 Maersk Alabama hijacking rescue, have recently toured Ghost but declined to comment for this story.

Sancoff knows it won’t be an easy sell, despite his venerable board members. “I think DOD is very, very nervous about working with small startup companies,” he says. Especially when the technology is so unusual. Sancoff tells the story of a Navy SEAL who paid him a visit: “He said, ‘Sir, look at that picture behind your desk of Ghost. That’s not a boat. No one knows what you’re doing. They don’t get it.’”

At 57, Sancoff has a full head of gray-brown hair and a faint New England accent. On the day of the hangar visit, he’s wearing blue loafers, jeans, and a short-sleeved white button-down patterned with tiny blue anchors. Ghost is Sancoff’s first attempt to build a weapons platform, but he’s never been shy about pursuing implausible ideas. “My whole philosophy in life has been this: I will only work on stuff where people will look at me and go, ‘Are you

crazy?” he says. “When I was very young I just said to myself, I’m not going to work on something someone else can

do - why waste my time? I’m going to work on the hardest problem.”

After attending vocational-technical high school in Lawrence, Mass., Sancoff saved up money and skipped college to start a machine shop. Mainly, he devised and manufactured prototypes for various local companies, including microwave filters and syringe pumps. “Did I want to go to college? Kind of, but I also wanted to start a business immediately,” says Sancoff. At 24, he sold the shop and left Lawrence for San Diego. “Steve Jobs was worth probably $50 million, and he was the same age as me. I thought, if he can do it, I can do

it - I mean, come on!”

In California, Sancoff got a job as a technical consultant for the video game company Sega. He next honed in on the medical device industry, inventing products including a computerized IV pump and a tool that allows surgeons to suture without a needle. (Resembling a gun, it grabs tissue, forces a thin filament through a tiny hole, and ties off a knot in one motion.) Over the next 20 years, he built and sold five

companies - Block Design, Block Medical, River Medical, Ivac Medical, and Onux

Medical - for a total of more than $500 million. Kevin Kinsella, founder of the La Jolla (Calif.)-based venture capital firm Avalon Ventures, whose investments include Zynga (ZNGA), the Broadway show Jersey Boys, and several technology and life sciences startups, met Sancoff during those early days. “He’s a guy that’ll take a stack of engineering magazines to read in bed, that sort of thing,” says Kinsella. “He’s got this great polymath engineering mind.”

FORWARD

VIEW - It is called the Ghost because it is virtually invisible to sonar and

radar detection through its aluminum and stainless steel construction, making it non-magnetic, its hull angles bare a resemblance those of the F-117 Nighthawk. It can perform several types of mission including anti-surface warfare

(ASuW), anti-submarine warfare (ASW), and mine countermeasures (MCM): ASuW armament consists of the M197 20mm rotary cannon and launch tubes that expel exhaust downward between the struts of the SWATH hulls, concealing and dissipating the thermal signature of the launch for BGM-176B Griffin missiles and Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System rockets, with an electro-optical/infrared

(EO/IR) sensor and radar; an ASW version could be equipped with an EO/IR sensor, radar, sonobuoy launch tubes, a dipping sonar, and four aft-firing torpedo tubes; an MCM version could be equipped with a towing boom to lower and raise two towed mine-hunting

sonars, such as the Kline 5000 or Raytheon AN/AQS-20A. The current Ghost costs $10 million per copy, is crewed by 3-5 sailors, has an endurance of 30 days, and can be partially disassembled to fit in a C-17 Globemaster III for transport if needed. There is room for 16 passengers with two 6 in (15 cm)-diameter round windows in the hull. It is designed for fleet protection for navies with few blue-water needs but require a small and affordable craft in large numbers for near-shore maritime border patrol and defense missions.

After the death of his father, a decorated Army sergeant who served under General George Patton in

World War II, Sancoff began contemplating ways to give back to his country. To him, that meant shifting his focus from medical devices to weaponry. In 2000, when suicide bombers in Yemen attacked the Navy’s USS Cole, Sancoff recalls, “I said, ‘Wait a minute: Some yahoo terrorists in a cheap little boat and $500 worth of explosives can kill 17 sailors on a billion-dollar

ship?” Not long afterward, he came across a 630-page U.S. Navy report on an exercise called Juliet, in which the Navy attacked a battle group with small, high-speed boats. By the end of the second day of simulated warfare, the U.S. had lost more than 20,000 servicemen. It seemed obvious that the Navy was in need of improved small craft.

As a teenager, Sancoff had spent several years helping a friend’s father fashion components for hydroplanes, a type of high-speed racing boat that skims across the surface of the water. Building off that knowledge, Sancoff began reading up on marine technology. To make a stable vessel that doesn’t shoot into the air, as surface-skimming hydroplanes are wont to do, the hull needed to be

anchored to the water. But how can one move something through the water without creating debilitating drag? The answer: Supercavitation. Among other benefits, the phenomenon makes craft more fuel-efficient and more stable for shooting at targets. The Russian military, Sancoff learned, had built a supercavitating rocket-powered

torpedo, which traveled at 200 knots, roughly four times as fast as American weapons. But the torpedo was difficult to steer. The problem, he realized, was that the propellers were pushing from the back, rather than pulling from the front. “If you push a pencil across a table, it’s very hard to keep it going straight,” Sancoff explains. “If you pull the pencil, it’s easy.”

Installing Ghost’s propellers in front solved not only the control problem but actually furthered the vessel’s supercavitation by helping to push water aside, making room for air coming from above the water. It also meant that the craft would potentially be more stable and have less drag than hydrofoils, which also have hulls that rise out above the water. “That was the eureka,” says Sancoff. “I immediately started designing the boat on my kitchen table with a pen and paper.”

After founding Juliet Marine, named for the disastrous Navy exercise, in 2007, Sancoff filed for more than a dozen patents for his technology and began building a full-scale

plywood mockup of Ghost’s hull. He set up Juliet Marine’s headquarters in downtown Portsmouth, N.H., in a white three-story house from 1725, bordered by a white picket fence and garden beds filled with broken clamshells.

GHOST is a super-cavitating stealth ship which can achieve 900 times less hull friction than a conventional watercraft.

In practice that may not be the case, but the theory behind the concept is

sound. The boat bears an uncanny resemblance to one of the SolarNavigator

designs, also a SWATH vessel, but propelled by electric motors and solar

powered. Click on the picture above to see the solar powered version.

In the spring of 2009, Juliet Marine secured a rental agreement for the Naval base hangar. “It was full of junk when we got

it - old wooden mockups of

submarines and that sort of thing,” says Sancoff, who had only four employees at that point. Investing $5 million of his own money, he built the first full-scale prototype in two years with the help of contractors.

A major challenge for Ghost is that the Navy’s policy is to buy only technologies in which it has announced interest. “It is not procedure to procure a system without established requirements,” says Commander Thurraya Kent, spokeswoman for the Navy’s research, development, and acquisitions arm. In the fall of 2009 the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) briefly expressed interest in funding the Ghost project, but Sancoff declined its request for a formal proposal because the agency required use rights to all of Juliet Marine’s patents. “I’m a startup

company - this is how I’ll earn money, by owning the technology,” says Sancoff. Darpa declined to comment.

Over the years, Sancoff sent the Office of Naval Research images of his design. “They laughed at me; they thought I was crazy,” he says. “‘Those jet engines can’t run underwater in those tubes. That boat can never be stable. You can never supercavitate those hulls.’ Obviously I was discouraged.”

In October 2009, after about six months working in the hangar, Sancoff got a frantic call from his patent attorney. “He said, ‘I got something in the mail, I’ve never seen anything like it, and I’ve been practicing for 35

years,” remembers Sancoff. The letter, from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, with a recommendation from the Office of Naval Research, turned out to be a secrecy order, forbidding Juliet Marine from filing its patents internationally or talking with anyone, including potential investors, about its technology. “They didn’t explain why.… They wouldn’t talk with my lawyer. They wouldn’t talk with me,” says Sancoff.

For two summers, Ghost’s trial runs were conducted only at night. “We were going out at like 3 a.m.,” says Joseph Curcio, a marine engineer who taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and designed

robotic systems for the Navy before joining Juliet Marine in 2010 as vice president of research and development. “We’d have to cover the [propellers] with a blanket and move the boat in the dark. We weren’t allowed to let anyone take pictures.”

The secrecy orders were lifted after two years, also without explanation. That’s when Kinsella of Avalon Ventures heard about

Ghost and joined the company’s board, investing $10 million. “We’ve never done a military application before,” he says, before pointing out that Sancoff has a strong track record as a serial entrepreneur. “I’ve always made money with this guy. He can squeeze a nickel until the buffalo pees.”

Ghost failed to lift out of the water on its first dozen trial runs. Then, one day in 2011, with Sancoff and Curcio at the helm, Ghost emerged from the

water. “We’d just gotten all the controls right,” says Curcio. “We were calling over to the chase boat, asking ‘Are we up? Are we up?’ and Tom [Richards]

radioed over, like, ‘I can’t believe it, I can see, like, four feet under the hull.’” Euphoria ensued. “We’d had all these experts telling us

… it’s going to nosedive and flip over,” says Sancoff. “And all of the sudden, it runs perfect. It’s not unstable at all.”

Not long afterward, Sancoff accidentally drove the craft into the rocks. “The Admiral was away on a business trip, so we got to blame him,” says Curcio. Admiral Richards generally captains the Ghost’s chase boat during trial runs. “We had no adult supervision,” adds Sancoff. “I was not happy with myself, to say the least.”

That’s when Juliet Marine hired Cliff Byrd, a 6-foot-3 former Special Warfare Combatant-Craft Crewman, who spent years as a boat specialist delivering and picking up Navy SEALS on dangerous missions. Byrd, 36, had served 12 years with the Navy, traveling more than 220 days a year to hot spots around the world.

“You’d think skydiving or all the other things we do, that you’d get injured from that, but actually it’s the boats that you take most of the beating on,” he says. “A lot of guys have back injuries, hips, ankles, knees, shoulders, you name

it - any joint, just because of all the shock your body goes through.”

The smoothness of Ghost’s ride is perhaps the team’s greatest point of pride. “I was riding down to Newport, and we had up to 8- to 10-foot seas,” says Byrd. “We’re sitting in here joking about it and not actually feeling anything.” Sancoff slept for half the ride. “But the chase boat that came along with us pounded through the ocean so bad,” he says. “They were seasick, throwing up. When we got to Rhode Island, I said, ‘Let’s go and get a steak,’ right? They couldn’t even eat.”

Roger Schaffer, a member of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, worked as a civilian contractor on Navy ship design for 42 years. He saw Juliet Marine give a presentation about Ghost earlier this year. “It’s difficult to come up with something new in a field like naval architecture, but they’ve managed to combine a number of features into an overall concept that looks quite attractive,” says Schaffer. “If the supercavitation technology of the Ghost proves successful, it will allow the Ghost to obtain significantly higher speed than

hydrofoils or SWATHs have been able to achieve.” That said, Juliet Marine faces a tough battle. “Normally, innovative ship designs stem from funded research by the Navy at one of their labs,” says Schaffer. “[Juliet Marine] also has a problem with the institutional bias the Navy tends to have against small crafts like the Ghost.”

In the face of budget cuts, Defense officials have asked companies to fund more of their own research, which is why Juliet Marine personnel are surprised they haven’t garnered more interest. Juliet Marine hopes things will change if the craft breaks the commercial SWATH speed record of 31 knots. So far, Ghost’s top speed is 29 knots, but Curcio says 50 knots is within reach, roughly the speed of Mark V boats, a formerly popular mode of transport for Navy SEALs that was discontinued in 2012.

Seven U.S. allies, including

Qatar, Israel, and Korea, have expressed interest in Ghost, according to Sancoff. “A lot of countries adopt new technology much more rapidly than the U.S.,” he says. “Do I want to see this boat in the Persian Gulf with another flag on the back of it? Not necessarily. But if that’s what it takes to make this company successful, to supply boats to the U.S. Navy, then we’ll do it,” he says. The

Wright

Brothers, he adds, got a contract from France before the U.S. government. “They thought they were crazy, too,” says Sancoff. “It took years for the Wright brothers to convince [the government] that an airplane might be viable.”

The potential market for new naval vessels will reach about $46 billion in the next nine years, according to AMI International, a global defense market analysis firm. Juliet Marine says Ghost’s technology could also be adapted to build stable, superfast torpedoes or unmanned sea

drones. Commercial possibilities include jet skis or craft for transporting workers to oil platforms. “These rich bankers who take helicopters from [Wall Street] to the Hamptons now, you know?” adds Kinsella. “If they don’t want to take a helicopter, the Ghost could take a bunch of people out there at high speed.” Juliet Marine is in talks with

Barclays (BCS) about an initial public offering, and Kinsella says the startup isn’t opposed to an acquisition by a larger defense contractor. The startup plans to build two additional boats by the end of the year, which will be used for weapons testing and demonstrations.

With its patents now available to the public, Juliet Marine’s staff worries other countries and companies will steal its technology. “The Chinese are probably already starting to knock this off,” says Sancoff, adding that hackers attempt to break into his company’s computer systems hundreds of times each month. One day in 2009, he arrived at Building 129 to find the locks broken. He assumes whoever did it wanted to photograph the boat’s parts; the break-in remains unsolved, he says.

On a sunny morning in July, Ghost is tethered to a buoy off the Portsmouth shipyard in the Piscataqua River. Curcio and Byrd climb aboard through the back door, above which is emblazoned New Hampshire’s motto: Live Free or Die. They’ll be manning the ship for a trip down the river out into three-foot swells in the open ocean.

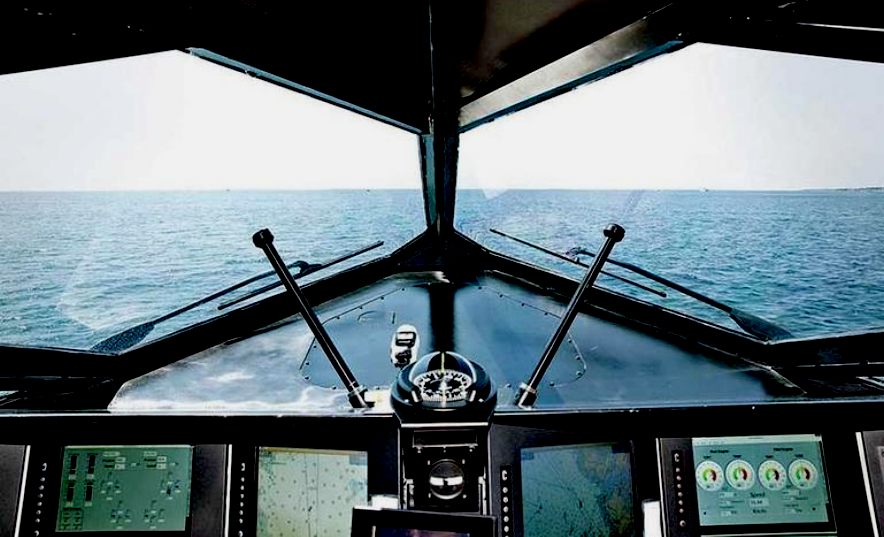

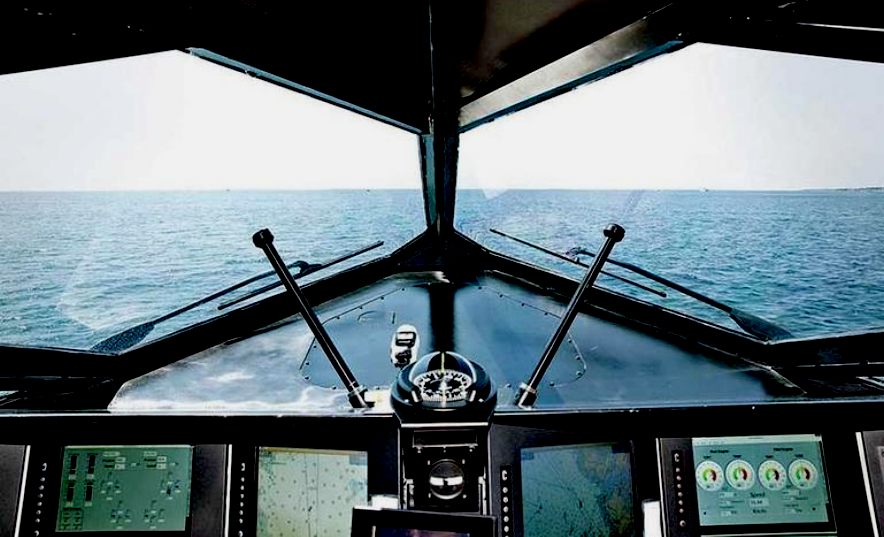

Up front, the cockpit is outfitted with large windshields fashioned from two-inch-thick glass. There are multiple screens displaying maps and Ghost’s various controls, but Byrd needs only the throttle and a four-inch joystick to steer the craft. As he turns on the engines and ventilation, the vessel sounds like an airplane lifting off. The back cabin, big enough to transport 16 people, is dimly lit. Seats clamped into the metal grid floor are outfitted with quick-release race car safety belts. There are no windows but for two round glass panes near the cabin floor, each with a diameter of about six inches. Through them, one sees the water gushing by—until the hull lifts up into the air. Then, against a blue backdrop of the ocean below, one sees only drops of spray against the portholes.

by Caroline Winter

DAILY MAIL

23 DECEMBER 2014

- INVENTOR'S AMAZING X-WING BOAT US NAVY

DOESN'T NEED

Inventor Greg Sancoff's sleek and futuristic Ghost warship is all revved up with no place to go.

The angular vessel looks like a waterborne stealth X-Wing fighter from Star

Wars. It rides atop underwater torpedo-shaped tubes powered by a pair of 2,000-horsepower gas turbine engines. Gyroscopes keep the ride smooth.

Despite all of its cutting-edge bells and whistles, Ghost might never be a familiar household name like Humvee, Apache and Abrams

- even if it works as advertised - because its creator built a warship the military is not convinced it needs.

‘It's a revolutionary program,’ said Sancoff, founder and CEO of Juliet Marine Systems. ‘Nothing like this has ever been built by anybody, not even the Navy.’

The Ghost rides on 12-foot-tall struts connected to engine assemblies Sancoff says take advantage of ‘supercavitation,’ traveling underwater inside a bubble of gas.

It is a new application of technology that the inventor insists will make Ghost fast

- it's so far hit about 35mph but its creator believes it can approach 60mph

- while staying stable even in rough seas.

But Sancoff has taken the usual step of spending $15million on a prototype that he hopes to sell to the Navy, turning upside down a process in which normally the military identifies a need before soliciting proposals and seeking funding.

‘The Navy is pretty skeptical of what we've been working on but they're starting to take us more seriously,’ said Sancoff, whose company operates out of a leased warehouse at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard.

Sancoff, who as a young man raced hydroplanes, came up with the design for the 60-foot-long vessel after terrorists using a small boat full of explosives nearly sank the USS Cole in 2000.

He thinks the Navy needs a fast patrol boat to protect larger and more costly warships when they're most vulnerable, like when they're passing through the Strait of Hormuz at the southern end of the

Persian Gulf.

The Ghost's smooth ride makes it an ideal platform for weapon systems

- and for transporting Navy SEALs, Sancoff said.

Supercavitation has been used to produce high-speed torpedoes but Sancoff said he is adapted it for the first time to propel a surface warship. As part of his design, dual propellers were moved to the front instead of the rear and underwater ailerons control the vessel, which banks like an airplane when it's turning.

Sadly for Sancoff, the Navy currently does not have a requirement for such a patrol boat, said Chris Johnson, spokesman for the Naval Sea Systems Command.

But the innovative design is at least worth a look, even if it turns out to be unfit for military use, according to retired Vice Adm. Pete Daly, CEO of the US Naval Institute, an independent, nonpartisan organization in Annapolis, Maryland.

‘The high ground for the US Navy is to take this and evaluate it and learn from it,’ Daly said. ‘The propulsion system could be valuable in other applications. You've got to keep that door open to innovation,’ he said.

Sancoff insists the military has expressed at least some interest in his company, which counts retired Navy admirals and one former US senator, John Sununu of New Hampshire, as board members.

‘Any time you're building something so different, you're going to find people that just don't understand it. You've really got to spend some time understanding what's going on here,’ Sancoff said.

Even in the best of times, the Navy tends to buy larger, multi-missions ships instead of smaller niche vessels. And the Navy's current budget

struggles pose perhaps the biggest obstacle.

Sancoff is also proposing marketing his vessel to other navies and wants to build a new version that'll be a bit bigger. He believes it will be flexible enough for other tasks, like anti-submarine and mine warfare operations.

Loren Thompson, a defense analyst at the Lexington Institute, said the small company faces an uphill battle.

The Navy's speedy new littoral combat ships are designed to fulfill the Ghost's proposed mission, and Thompson is skeptical that the Navy would be willing to go out on a limb for all-new design for a ship that's too small and light to accommodate heavy

armor and bigger weapon systems.

Juliet Marine needs plenty of money, and perhaps a friend or two in Congress, he said, to circumvent an acquisition process that poses obstacles for small startups like Juliet, which has 15 employees.

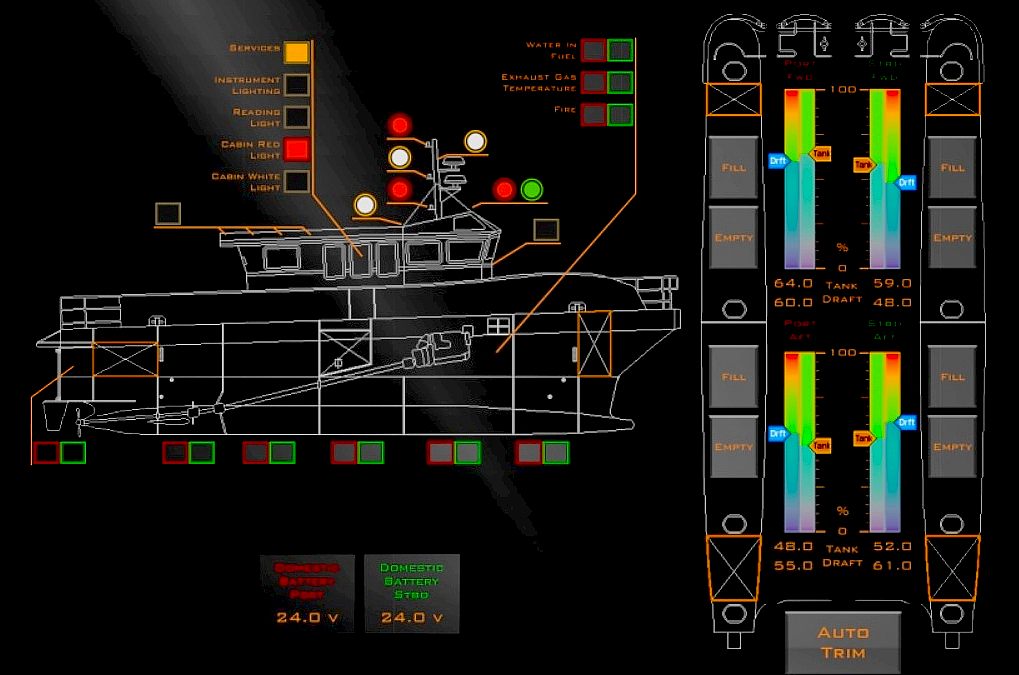

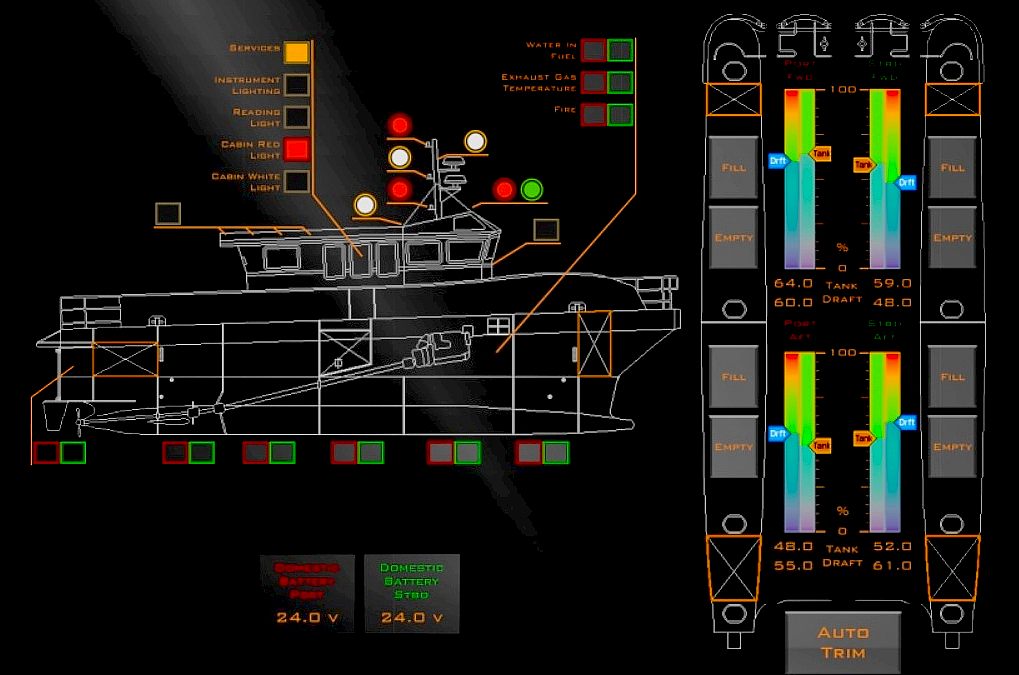

TRIM

- A

system like this was used on the SolarNavigator 1/10th scale model in

1995. If the system had been developed, and with robots coming of age,

such a system would more than likely have been automatic today.

15

DECEMBER 2015 - BALANCING SWATH VESSELS

Indian-owned and UK-headquartered Servowatch, the marine systems integrator and automation specialist, has introduced a new trim and draught stability optimiser, ServoTrim, designed specifically to ‘balance the draught’ of

SWATH (Small Waterplane Area Twin Hull) vessels.

The first ServoTrim system will be delivered to a Taiwanese shipyard for integration with a 22m wind farm supply vessel under construction for a UK-based operator.

Wayne Ross, Chief Executive Officer, Servowatch, said: “The need to calculate ship trim and draught is one of the most important measurements operators take to ensure vessel stability and safety. ServoTrim is designed to control a balanced draught for a vessel, providing automatic flow control after manual trim has been set.

“While the system is not a fully automatic dynamic stabilisation system, the system can be reset to automatically recognise the optimum trim and draught for different operational conditions, such as loading or unloading fuel, supplies and personnel.”

The ServoTrim installation for the SWATH wind farm supply vessel has been designed specifically for a four ballast tank configuration, with each tank fitted with a single sensor to provide concurrent tank, pump and valve status monitoring. Draught sensors are sited at each ‘corner’ of the vessel.

“Other types of vessels can benefit from ServoTrim,” said Servowatch Systems’ Sales Director Martyn Dickinson. “It can be easily applied to inland waterway barges and heavy lift platforms. Certainly situations may exist where the platform needs a dedicated system which can provide a draught and trim correction function to counter uneven weight distribution.”

ServoTrim employs high-accuracy hydrostatic level transmitters to measure ballast tank levels and provide multi-port draught indications. To protect the sensors from external moisture, they are encased in IP68 and IP69K standard stainless steel housing.

Once the Servowatch ServoTrim system has been commissioned, the crew manually sets the trim ‘datum point’ when the vessel is at rest and the loading of

fuel, commodities and personnel is complete and stable.

This is achieved by manually operating the ballast tanks fill and empty control system until the ‘correct’ trim is obtained. The data is then entered into the control system memory by selecting the automatic control function. The control system takes its reference signal from four draught sensors mounted within a vented pipe inside the vessel.

Each ballast tank is equipped with a level sensor to determine the depth of the water in each ballast tank. When the ‘automatic’ mode control is selected the ballast tank sensor data and the draught sensor data is fed into the control system to form a ‘datum point’ for each ballast tank.

The system automatically controls the water level in each ballast tank to maintain the vessel selected ‘datum point’ within the ‘dead bands’ of the control system. It automatically checks the ‘datum point’ every 10 minutes.

SERVOWATCH

CONTACTS

Servowatch Systems Ltd.

Endeavour House,

Holloway Road, Heybridge,

Maldon, Essex CM9 4ER

Tel: +44 (0) 1621 855 562

Email:

sales@servowatch.com

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Dailymail

UK news Maine entrepreneur builds 15M X Wing stealth speedboat fly

water deliver troops battle Pentagon says doesn't need it Military

factory ships Juliet Marine Ghost Stealth Boat Twitter

Justin_Manley PR

Newswire

Juliet Marine Systems appoints Justin Manley vp of business development UK

business

insider juliet marine ghost ship 2014 10 Businessweek

authors Caroline Winter Bloomberg

2014 August 21 Juliet Marines ghost boat will be hard sell to u dot s navy Wikipedia

Juliet_Marine_Systems_Ghost

Maritimejournal.com/news101/onboard-systems/monitoring-and-control/balancing-swath-vessels Maritime

journal vessel build and maintenance ship and boatbuilding swath gets

smarter Abeking Juliet

Marine http://www.servowatch.com/ http://www.militaryfactory.com/ships/detail.asp?ship_id=Juliet-Marine-Ghost-Stealth-Boat https://twitter.com/justin_manley http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/juliet-marine-systems-appoints-justin-manley-vp-of-business-development-300081413.html http://uk.businessinsider.com/juliet-marine-ghost-ship-2014-10 http://www.businessweek.com/authors/505-caroline-winter http://www.bloomberg.com/bw/articles/2014-08-21/juliet-marines-ghost-boat-will-be-hard-sell-to-u-dot-s-dot-navy https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juliet_Marine_Systems_Ghost

http://www.maritimejournal.com/news101/onboard-systems/monitoring-and-control/balancing-swath-vessels http://www.maritimejournal.com/news101/vessel-build-and-maintenance/ship-and-boatbuilding/swath-gets-smarter

https://www.abeking.com/

|