|

BACKGROUND

The Maersk Alabama hijacking was a series of maritime events that began with four pirates in the Indian Ocean seizing the cargo ship MV Maersk Alabama 240 nautical miles (440 km; 280 mi) southeast of the port city of Eyl, Somalia. The siege ended after a rescue effort by the U.S. Navy on 12 April 2009. It was the first successful pirate seizure of a ship registered under the American flag since the early 19th century. It was the sixth vessel in a week to be attacked by pirates who had previously extorted ransoms in the tens of millions of dollars.

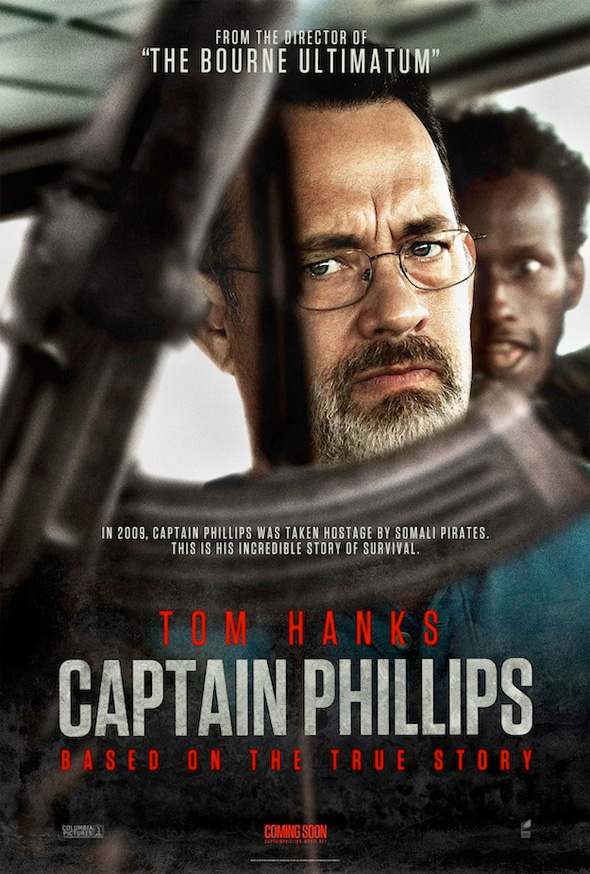

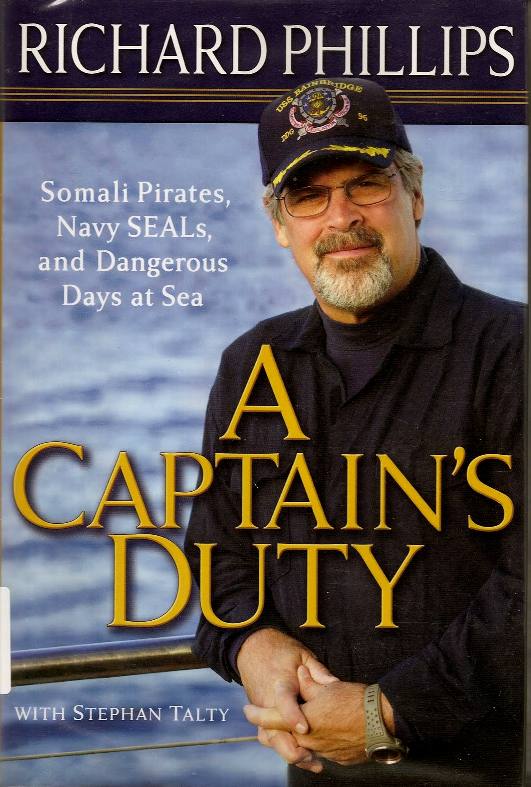

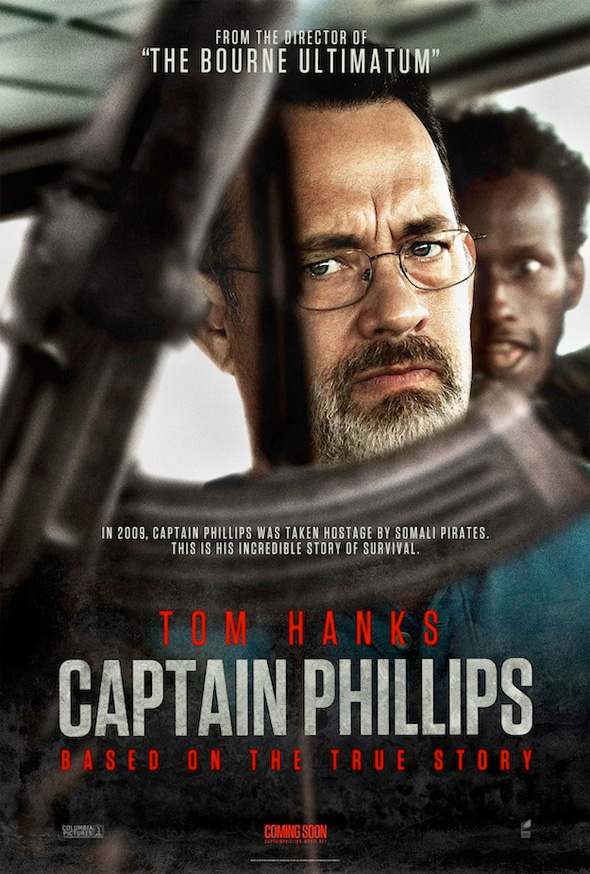

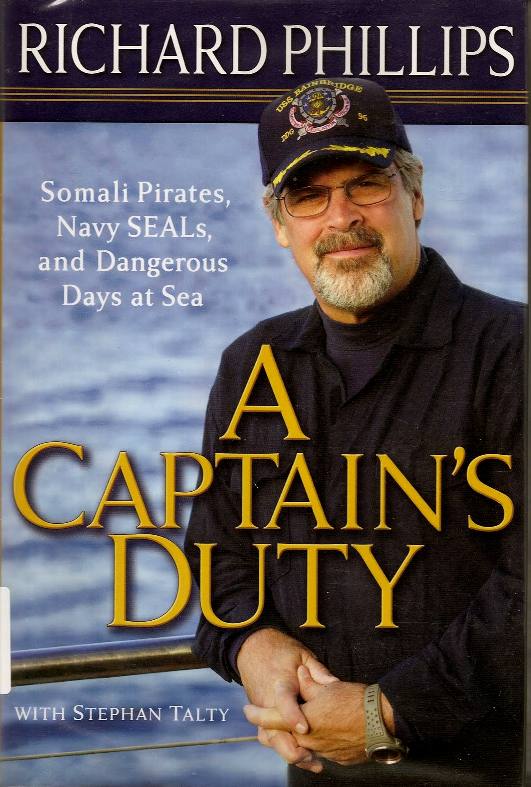

The story of the incident was reported in the book A Captain's Duty: Somali Pirates, Navy SEALs, and Dangerous Days at Sea (2010) by Stephan Talty and Captain Richard Phillips, who had been master of the vessel at the time of the incident. The hijacking also inspired the 2013 film Captain Phillips, with Tom Hanks playing Richard Phillips in the title role, Barkhad Abdi playing Abduwali Muse and Faysal Ahmed playing Najee.

HIJACK TIMELINE

he ship, with a crew of 20, loaded with 17,000 metric tons of cargo, was bound for Mombasa, Kenya. On 8 April 2009, four pirates based on the FV Win Far 161 attacked the ship. All four of the pirates were between 17 and 19 years old, according to U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates.

The crew members of the Maersk Alabama had received anti-piracy training from union training schools, and had drilled aboard the ship a day previously. Their training included the use of small arms, anti-terror, basic safety, first aid, and other security-related courses. When the pirate alarm sounded early on Wednesday, 8 April, Chief Engineer Mike Perry brought 14 members of the crew into a "secure room" that the engineers had been in the process of fortifying for just such a purpose. As the pirates approached, the remaining crew fired flares; in addition, Perry and 1st A/E Matt Fisher swung the ship's rudder, which swamped the pirate skiff.

Nonetheless, the ship was boarded. Perry had initially taken main engine control away from the bridge and 1st A/E Matt Fisher had taken control of the steering gear. Perry then shut down all ship systems and the entire vessel "went black." The pirates captured Captain Richard Phillips and several other crew members minutes after boarding, but soon found that they could not control the ship.

Perry remained outside the secure room lying in wait, knife in hand, for a visit from the pirates who were trying to locate the missing crew members in order to gain control of the ship and presumably sail it to Somalia. Perry tackled the ringleader of the pirates and took him prisoner after a cat-and-mouse chase in a darkened engine room. The seamen on watch at the time stabbed one pirate in the hand.

The crew attempted to exchange the pirate they had captured for the captain, but the exchange went awry and after the crew released their captive, the pirates refused to honor the agreement. Captain Phillips escorted the pirates to a lifeboat to show them how to operate it, but then the pirates fled with the Captain.

On 8 April 2009, the destroyer USS Bainbridge was dispatched to the Gulf of Aden in response to the hostage situation, and reached the Maersk Alabama early on 9 April.

The Maersk Alabama was then escorted from the scene under armed guard towards its original destination of Mombasa where Captain Larry D. Aasheim retook command of the ship. Phillips had relieved Aasheim nine days

earlier. CNN and Fox News quoted sources stating that the pirates' strategy was to await the arrival of additional hijacked vessels carrying more pirates and additional hostages to use as

human shields.

RESCUE

A stand-off ensued between the USS Bainbridge, the frigate USS Halyburton, and the pirates' lifeboat from the Maersk Alabama from 9 April 2009, where they held Captain Richard Phillips hostage. The lifeboat itself was covered and contained plenty of food and water but lacked basic comforts, including a toilet or ventilation. The Bainbridge was equipped with a ScanEagle drone and RHIB boats. The Halyburton held two SH-60B helicopters on board. Both vessels stayed several hundred yards away, out of the pirates' range of fire. A P-3 Orion surveillance aircraft secured aerial footage and reconnaissance. Radio communication between the two ships was established. Four foreign vessels held by pirates headed towards the lifeboat. A total of 54 hostages were on two of the ships, citizens of China, Germany, Russia, the Philippines, Tuvalu,

Indonesia, and Taiwan.

On 10 April 2009, Phillips attempted to escape from the lifeboat but was recaptured after the captors fired shots. The pirates then threw a phone – and a two-way radio dropped to them by the U.S. Navy – into the ocean, fearing the Americans were somehow using the equipment to give instructions to the captain. The U.S. dispatched another warship, amphibious assault ship USS Boxer, to the site off the Horn of Africa. The pirates' strategy was to link up with their comrades, who were holding various other hostages, and to get Phillips to Somalia where they could hide him and make a rescue more difficult for the Americans. Anchoring near shore would allow them to land quickly if attacked. Negotiations were ongoing between the pirates and the captain of the Bainbridge, who was under the direction of FBI hostage negotiators. The captors were also communicating with other pirate vessels by satellite phone.

However, negotiations broke down hours after the pirates fired on the Halyburton not long after sunrise on Saturday, 11 April 2009. The American frigate did not return fire and "did not want to escalate the situation". No crew members of the Halyburton were injured from the gunfire, as the shots were fired haphazardly by a pirate from the front hatch of the

lifeboat.

"We are safe and we are not afraid of the Americans. We will defend ourselves if attacked", one of the pirates told Reuters by satellite phone. Phillips' family had gathered at his farmhouse in Vermont awaiting a resolution to the situation.

On Saturday, 11 April 2009, the Maersk Alabama arrived in the port of Mombasa, Kenya under U.S. military escort. An 18-man security team was on board. The

FBI then secured the ship as a crime scene.

Commander Castellano stated that as the winds picked up, tensions rose among the pirates and "we calmed them" and persuaded the pirates to be towed by the Bainbridge.

On Sunday, April 12, Navy SEAL marksmen opened fire and killed the three pirates on the lifeboat; Phillips was rescued in good condition. The Bainbridge captain Commander Frank Castellano, with prior authorization from higher authority, ordered the action after determining Phillips' life was in immediate danger, citing reports that a pirate was pointing an AK-47 assault rifle at Phillips' back. Navy SEAL snipers, from "SEAL Team Six", opened fire nearly simultaneously from Bainbridge's fantail, killing the three pirates with bullets to the head. The SEALs had arrived Friday afternoon after being parachuted into the water near the Halyburton, which later joined with the Bainbridge. At the time, the Bainbridge had the lifeboat under tow, approximately 25 to 30 yards astern. One of the pirates killed was named Ali Aden Elmi, the last name of another was Hamac, and the third has not been identified in English-language press reports. A fourth pirate, Abduwali Muse, aboard the Bainbridge and negotiating for Phillips' release while being treated for an injury sustained in the takeover of Maersk Alabama, surrendered and was taken into custody.

The bodies of the three dead pirates were turned over by the U.S. Navy to unidentified recipients in Somalia in the last week of April 2009.

LAWSUIT

On 27 April 2009, 'Maersk Alabama' crew member Richard E. Hicks filed a lawsuit against his employer, Waterman Steamship Corporation and Maersk Line, Ltd., for knowingly sending him into pirate-infested waters near Somalia. Houston attorney Brian Beckcom, who is representing Richard Hicks and eight other members of the crew, said that Captain Phillips knowingly and willingly put the crew in danger by ignoring reports of recent pirate attacks and disregarding warnings to remain at least 600 miles from the coast of Somalia. In August 2011, the Court of Appeals of Texas dismissed Waterman from the litigation.

PIRATE TRIAL

The surviving pirate, Abduwali Muse, was held on the USS Boxer and was eventually flown to the U.S. for trial. In a federal courtroom in New York City, prosecutors brought charges that included piracy, conspiracy to seize a ship by force, and conspiracy to commit hostage-taking. Muse's lawyers asked that he be tried as a juvenile, alleging he was either 15 or 16 years old at the time of the hostage taking, but the court ruled Muse was not a juvenile and would be tried as an adult. He later admitted he was 18 years old and pleaded guilty to piracy charges and was handed a prison sentence of 33 years and nine months.

UDT-SEAL MUSEUM

The owners of U.S. Maersk Alabama donated the bullet-marked 5-ton fiberglass lifeboat upon which the pirates held Captain Phillips hostage to the National Navy UDT-SEAL Museum in Fort Pierce, Florida, in August 2009. The lifeboat had recently been on loan to National Geographic for its "Real Pirates" exhibition at the Nauticus marine science museum in Norfolk, Virginia. The producers of the Captain Phillips film visited the Museum in the process of re-creating the lifeboat and interiors for the set. An example of the Boeing Insitu ScanEagle used to monitor the crisis is also on display, as is the Mark 11 Mod 0 (SR-25) sniper rifle of the type used by the

U.S. Navy SEALS to kill the pirates and free Phillips.

PIRACY VIOLENCE AT SEA MYTHS

2014

"In the last five years, pirates have killed at least 411 fishermen and wounded at least 1,000 more, suggested Mujibur Rahman, Chairman of Cox's Bazar District Fishing Trawler Owners Association (DFTOA). According to the DFTOA, pirates attacked more than 1,000 fishing boats, abducting more than 3,000 fishermen, killed over 45 and collected more than $1.28 million in ransoms from fishery owners of two coastal towns - Chakaria and Maheshkhali, alone from late 2011 to late 2012,"

The

above was reported in a Bangladeshi paper in April 2013. If true then this staggering level of violence eclipses that of any other reports of actual or alleged pirate violence - be it in Africa or South East Asia. Like most forms of maritime "piracy" (which often technically do not even qualify as piracy under the UNCLOS definition) Bangladeshi piracy is an acknowledged local phenomenon that primarily affects locals and local or regional economic interests.

International media and watchdogs often only sit up and pay attention when international shipping is affected. Hence, whenever a region grabs the headlines for pirate attacks, we read bizarre news about "the world's most violent pirates", but only when their attacks cause casualties amongst the crews of internationally-trading vessels. Some of this has a whiff of fear-mongering about it and generally leaves seafarers confused and frightened about the nature of the piracy threats in the various parts of the world.

This is not to say that those casualties reported are not a cause for concern, but what appears to be lacking is a discussion informed by the most basic analysis of the facts. For starters, violence levels in piracy worldwide would appear to be much higher than what is commonly circulated. Like the piracy phenomenon itself, violence is underreported when incidents do not meet certain legal criteria or definitions of piracy.

This is legally correct, but it is misleading when assessing the potential for violence (and thus planning appropriate risk mitigation) since the local perpetrators are often the same who commit crimes against local shipping or at least they hail from similar backgrounds. This is true for Somalia, where many of the original pirates were involved in criminal activity against Somali and Yemeni fishing vessels. It is also true for the Gulf of Guinea, where the same Niger Delta youths who prey on inshore traffic and kidnap oil workers are also hired by organised criminals to hijack tankers. Finally, in South East Asia, local criminals (including active or former military personnel) form the operational nucleus for many of the maritime scams including tug-jacking and product theft.

South and South-East Asia Piracy

The local nature of piracy in Asia, as described above, makes it less newsworthy for the international community. When international shipping (though often in a regional context) is affected, like tanker hijackings, then it frequently involves a strong collusive element involving government security forces, hijackers and owners that does not encourage reporting. However, isolated reporting like the one on Bangladeshi fishermen, or the killing of seven Thai seamen off Songkhla port in October 2013, or the slaying of nine Filipino seafarers in the southern Philippines in December 2013 (with some of the victims being beheaded), suggests a particularly ruthless streak amongst some of Asia's pirates that has no equivalent in Africa.

Historically, many of South East Asia`s ghost ship's original crews in the 1990s were also disposed of by the hijackers - many disappeared without a trace.

Gulf of Guinea Piracy

It has become fashionable to brand the pirates of the Gulf of Guinea as particularly violent. This perception is largely based on anecdotal reports that date back to the 1970s, where European crews faced down pirates on the decks of their ships. It was later reinforced through the rise of the Niger Delta youth militias, who espoused violence as the only means to address their grievances. The level of aggression amongst those youths is felt to be intimidating even by the Niger Delta population, as a number of studies on the Niger Delta Youths have shown. Hence it is not a "natural" Nigerian, let alone West African, trait. Some of this militant attitude carried over to commercially-driven piracy, although the focus of violent groups in the Niger Delta remains on domestic issues, with most of the brutality being reserved for gang fights and disposal of political opponents.

In order to make Nigerian piracy comparable to that in other regions, the focus has to be on the post-insurgency period commencing in October 2009 to eliminate insurgency-related effects.

Between that date and June 2014 Risk Intelligence has documented 738 attacks in West Africa - of which consistently between 80-100 incidents per year occurred in the Gulf of Guinea. Twenty of those incidents involved fatalities - all in or near Nigerian waters. Seven of those 20 incidents involved government security forces. Of the 37 fatalities recorded in that period, 15 were security personnel.

Of the remaining 22, 12 were killed in incidents on inshore waterways. The remaining ten were on offshore vessels, fishing vessels and foreign merchant vessels. Four killings took place in cold blood - two of them on foreign vessels.

More generally, African pirate violence comes across as casual violence, lack of restraint or, especially in the Gulf of Guinea, poor weapons discipline. A study by Risk Intelligence of 93 tanker hijackings in the Gulf of Guinea between 2010 and 2013 showed that the number of weapons discharges had increased, but had not caused a rise in casualties. Crew testimonies suggest that both in East and West Africa drug and alcohol abuse play a major role in attacker violence and erratic behaviour. As the above figures for the Gulf of Guinea show, most casualties have involved security forces, and inshore incidents - not attacks on transiting foreign-flagged vessels. Gulf of Guinea pirates are well armed, and often intimidating, but in terms of fatal attacks there is no reason for them to be singled out over pirates elsewhere.

In the case of Gulf of Guinea - or specifically Nigerian - pirates, there is the mantra that they will attack even when there is an embarked government security force team. This explanation exhibits a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of Nigerian pirates. They attack, and kill, because they are facing government security forces. The reason is that the pirates are the same youths who face both oppression and extortion by corrupt security forces in the Niger Delta. This combative attitude in the face of armed opposition is largely unique to Nigeria (or Nigerian pirates with a Niger Delta background) and not reflective of general pirate behaviour in West Africa. It also suggests that embarking government security forces may not be as effective in reducing the risks to crews as the embarkation of PCASP has been in the Indian Ocean.

Conclusion

Whatever the actual numbers of Bangladeshi fishermen killed, it is a good example of a specific local situation with unique drivers that are often overlooked by analyses on pirate violence which focus on numbers and trends only in the context of international shipping. The local context provides explanations as to when and where - and against whom - violence can be expected and also as to the true potential for violence in any given region of the world.

Pirate violence is an emotionally charged subject. Better understanding hinges on more accurate and comprehensive reporting and informed analysis. It also requires a common understanding of what constitutes "violence". Fear-mongering and perpetuation of unfounded myths are unhelpful in alleviating anxieties amongst seafarers and in preparing them for dealing with the problem.

Security companies and specialized media in particular have a responsibility to not stoke the flames for fear of losing relevance. Often as not, good security advice constitutes what enables clients to make sound commercial decisions and protect their crews more effectively when based on the most objective facts available.

The Author

Dirk Steffen is the Director Maritime Security for Risk Intelligence. He has been covering the Gulf of Guinea as a maritime security consultant and analyst since 2004.

e: ds@riskintelligence.eu

w: www.riskintelligence.eu

t: +45 70 266330

As published in the August 2014 edition of Maritime Reporter & Engineering News -

http://magazines.marinelink.com/Magazines/MaritimeReporter

http://maritimeglobalnews.com/news/challenging-myths-pirate-violence-b6rbdg

http://www.maritimeprofessional.com/News/376369.aspx

Director

Paul Greengrass and his wife Joanna at the London premiere of Captain

Phillips in 2013. Paul also directed two of the 'Bourne' action movies. Nice

one.

CAPTAIN PHILLIPS 2013 MOVIE - TOM HANKS

Captain Phillips is a 2013 American action thriller film directed by Paul Greengrass and starring Tom Hanks and Barkhad Abdi. The movie is inspired by the 2009 Maersk Alabama hijacking, an incident during which merchant mariner Captain Richard Phillips was taken hostage by pirates in the Indian Ocean led by Abduwali Muse.

The screenplay was written by Billy Ray, and is based on the book A Captain's Duty: Somali Pirates, Navy SEALs, and Dangerous Days at Sea (2010) by Richard Phillips with Stephan Talty. Scott Rudin, Dana Brunetti and Michael De Luca served as producers on the project. The film received six Academy Award nominations including Best Picture and Best Supporting Actor for Barkhad Abdi. The film premiered at the 2013 New York Film Festival, and was released on October 11, 2013. Faysal Ahmed portrayed Najee as a major villain in the plot.

PLOT

Richard Phillips (Tom

Hanks) takes command of the MV Maersk Alabama, an unarmed container ship from Port of Salalah in Oman, with orders to sail through the Gulf of Aden to Mombasa, round the Horn of Africa. Wary of pirate activity off the coast of Somalia, the captain orders strict security precautions on the vessel and carries out practice drills.

During a drill, the vessel is chased by Somali pirates in two skiffs; Phillips succeeds in outrunning them when one gives up after hearing Phillips on the radio calling for immediate military air support (a bluff) and the other loses engine power after running into the rough water Captain Phillips created. The next day one of the skiffs returns with four heavily armed pirates led by Abduwali Muse (Barkhad Abdi); they are carrying a ladder they had hastily welded the night before. Despite the best efforts of Phillips and his crew, the pirates board and take control of the Maersk Alabama, capturing Captain Phillips after he cuts the ship's engine power and tells the crew to hide in the ship's engine room. Phillips offers Muse the contents of the ship's safe ($30,000), but under orders from his boss (the local Somali faction leader) Muse's plan is to ransom the ship and crew in exchange for millions of dollars of insurance money from the shipping company.

A crew member manages to cut the ship's emergency power, plunging the lower decks into darkness. As Muse, the

pirate

captain, attempts to search the engine room, the crew members overpower him. Negotiating with the other three pirates, one with badly injured feet, the crewmen arrange to trade Phillips for Muse and the ship's lifeboat. The pirates force Phillips onto the lifeboat and launch it, intending to hold the captain for ransom.

As the lifeboat heads for the shore, tensions flare between the pirates as they run low on the stimulant herb khat, lose contact with their mother ship, and are later intercepted by the U.S. Navy destroyer USS Bainbridge. Once additional U.S. Navy ships arrive, Phillips attempts to negotiate with Muse, who asserts that he has come too far and will not surrender. In the meantime, the Bainbridge's captain Frank Castellano (Yul Vazquez) is ordered to prevent the pirates from reaching the mainland by whatever means necessary.

That night, Phillips is able to escape and swims towards the ships. The navy cannot identify the swimmer as Phillips, and therefore they take no action. The pirates fire shots at him; he swims back to the lifeboat. The further agitated pirates are also unaware that a SEAL Team has parachuted in to intervene.

While three SEAL marksmen get into positions to fire a simultaneous shot at each of the pirates on the lifeboat, Castellano and the SEALs continue to try to negotiate with the pirates, eventually taking the lifeboat under tow. Eventually, Muse agrees to board the Bainbridge, believing he will join his clan elders in negotiating Phillips's ransom. In the lifeboat, one of the more agitated pirates, Najee, catches Phillips writing a goodbye note to his wife. When he tries to take the note away, Phillips attacks Najee, but is quickly restrained and beaten.

Najee decides to take full control; the pirates tie Phillips up and blindfold him, and the Bainbridge crew stop the tow. As Phillips is about to be executed, the three SEAL marksmen finally get three clear shots and simultaneously kill the pirates. On board the Bainbridge, Muse is taken into custody and arrested for piracy. Phillips is rescued and treated. He is in shock and disoriented, but he thanks the rescue team for saving his life.

CAST

Tom Hanks as Richard Phillips, captain of the MV Maersk Alabama

Barkhad Abdi as Abduwali Muse, pirate leader

Catherine Keener as Andrea Phillips

Faysal Ahmed as Najee

Michael Chernus as Shane Murphy, first officer of MV Maersk Alabama

David Warshofsky as Mike Perry, chief engineer, MV Maersk Alabama

Corey Johnson as Ken Quinn, helmsman, MV Maersk Alabama

Chris Mulkey as John Cronan, senior crew member, MV Maersk Alabama

Yul Vazquez as Commander Frank Castellano, commanding officer, USS Bainbridge

Max Martini as U.S. Navy SEAL commander

Omar Berdouni as Nemo, Somali-language translator working for the US Navy as part of Mission Essential

Mohamed Ali as Assad

Barkhad Abdirahman as Bilal

Mahat M. Ali as Elmi

Issak Farah Samatar as Hufan

MOVIE PRODUCTION

Shortly after the publication of Richard Phillips's memoir A Captain's Duty in 2010, Sony Pictures optioned the film rights. In March 2011, actor Tom Hanks attached himself to the project after reading a draft of the screenplay by Billy Ray. During the following June, director Paul Greengrass was offered the helm of the then-untitled film adaptation. A worldwide search subsequently began to find the film's supporting Somali cast. From this search, Barkhad Abdi, Barkhad Abdirahman, Faysal Ahmed, and Mahat M. Ali were chosen from among more than 700 participants at a 2011 casting call at the Brian Coyle Community Center in Cedar-Riverside, Minneapolis. According to the search casting director, Debbie DeLisi, the four actors were selected because they were "the chosen ones, that anointed group that stuck out."

Producers visited the National Navy UDT-SEAL Museum to see the bullet-scarred, five-ton fiberglass lifeboat aboard which the pirates held Capt. Phillips hostage so that they could accurately re-create the boat and interiors for the set. They were also able to view an example of the Boeing Insitu ScanEagle UAV, used to monitor the crisis, as well as the Mark 11 Mod 0 (SR-25) sniper rifle, (the type used by the U.S. Navy SEALs), both on display at the museum also.

Principal photography for Captain Phillips began on March 26, 2012. Filming took place off the coast of Malta in the Mediterranean Sea. Nine weeks were spent filming aboard the Alexander Maersk, a container ship identical to the Maersk Alabama; it was chartered on commercial terms. The USS Truxton, an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer and sister ship of USS Bainbridge, served as a set piece in the film.

The

three studios involved in production were:

* Michael De Luca Productions

* Scott Rudin Productions

* Trigger Street Productions

BOX OFFICE RECEPTION

The movie was distributed by Columbia Pictures. Captain Phillips grossed $25.7 million in its opening weekend, good for second place at the box office behind Gravity's $43.2 million. As of January 14, 2014, the film has grossed $105,010,295 in North America, and $109,603,525 in other countries, for a worldwide total of

$214,613,820, against a small budget of $55 million dollars.

Captain Phillips premiered on September 28, 2013, opening the 2013 New York Film Festival. The film was praised for its direction, screenplay, production values, cinematography, and the performances of Tom Hanks and Barkhad Abdi.

Captain Phillips received widespread critical acclaim. Film review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reports a 93% approval critic response based on 228 reviews, with a "Certified Fresh" and an average score of 8.3/10. The site's consensus reads: "Smart, powerfully acted, and incredibly intense, Captain Phillips offers filmgoers a Hollywood biopic done right—and offers Tom Hanks a showcase for yet another brilliant performance." Metacritic gives the film a score of 83/100 based on 48 reviews of a "Universal Acclaim". Film critic David Palmer gave the film a rare 10 out of 10, stating it was unbelievably intense and the climax featured some of the best acting he had ever seen. It was his top film of 2013.

The film was nominated for 4 Golden

Globes, including Best Picture (Drama), Best Actor in a Drama (Hanks), Best Supporting Actor (Abdi) and Best Director (Greengrass). It did not win in any of the categories.

MOVIE

PREMIERE OCT 2013

NAIROBI (Oct 11, 2013): On Somalia's high seas, ferocious pirates hijack a container ship but US special forces finally battle them off: the latest Hollywood film 'Captain Phillips', based on a real story.

In reality though, such daring rescues have been rare, and some 90 sailors languish in the hands of Somalia's gun-toting pirates, their boats sunk and no ransom in sight, many already held for more than two years.

'Captain Phillips', released Friday and starring Oscar winner Tom Hanks as the embattled captain, recounts the story of the Maersk Alabama, a vessel with a US crew delivering aid to Africa that was hijacked in April 2009 off the Horn of Africa.

The crew fought back, kept control of the ship and overpowered one of the attackers, prompting the pirates to leave the vessel and hold Phillips hostage on a lifeboat.

After a dramatic three-day standoff, Navy Seals marksmen killed the pirates and rescued Phillips, who returned home to a hero's welcome.

But those stuck in Somalia do not come from countries able or willing to stage such commando rescues, and the owners of their ships abandoned ransom talks after the vessels sank.

"The Maersk Alabama was a fairly unique case... but for those being held now, there is no fairytale ending," said John Steed, who heads an internationally-backed liaison body, the Secretariat for Regional Maritime Security.

"These are poor people from poor families, and they simply do not have the money to pay the ransom

- any ransom - that the pirates are demanding for their release," he added.

Some 90 sailors and fishermen are still being held, many from poor families in Asia, as well as Yemeni fishermen on six boats being used by the pirates as "mother ships", floating bases from which to launch their skiffs and attack large commercial vessels far out to sea.

Steed recounts gruesome accounts of how some hostages have "been tortured while they're on the telephone with their families" including having their ears cut off.

For many of the hostages, Steed's team is one of only a handful of organisations still interested in their plight, liaising between the

ship owners, the pirates and the desperate families.

"These pirates can wait 10 years for a payment, but they are still not going to get anything from these hostages," said Roy Paul, who heads the Maritime Piracy Humanitarian Response, a coalition supporting captured seafarers.

Several have held for several years, with no apparent hope of release on the horizon, and the pirates still steadfast in their belief they can still extort cash from their prisoners' impoverished families.

Foreign special forces have rescued others held in

Somalia, including one last year by US elite commandos who swooped in by helicopter to free two aid workers held for three months on land in Somalia.

There is no hope of such rescue for the remaining hostages.

Earlier this year, families of sailors from the MV Albedo - a Malaysian-flagged container ship captured in November 2010 but which sank close to shore in July in rough seas

- wrote a desperate appeal to the pirates.

"Now that the vessel has sunk, the owner has no interest to pay money and rescue the crew," the letter read.

"We appealed to everyone in this world to pay money towards the release of our people, but no one listened... We are very poor people, we even do not have any money to pay for medicines, school fees, buy food for our children."

The hostages include nationals from Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Iran, The Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Vietnam and Yemen.

Last year, the pirates extorted over 31 million dollars (24 million euros) in ransom payouts, according to

UN estimates.

"We're in almost daily contact, negotiating for their release on humanitarian grounds," said Steed, a former British army colonel.

The sums the pirates demand exceed anything the families of the hostages left can raise.

But despite the apparent hopelessness of the situation, he points to the release last year of 14 sailors from Myanmar, held in similarly grim conditions.

At their peak in January 2011, Somali pirates held 736 hostages and 32 boats.

Rates of attacks have tumbled in the past two years, prompted partly by the posting of armed guards on boats and navy patrols, but the decline in successful attacks is also a complicating factor.

"Their business model is broken and is not producing results... There hasn't been a

successful attack in over a year," Steed added. "But the problem is the pirates likely owe people money and need to recoup their costs."

Three

stories from different countries about modern day piracy, all made into

movies

PIRATES

OF THE 20th CENTURY

Pirates of the 20th Century

is a 1979 Soviet action/adventure film about modern piracy. The film was directed by Boris Durov, the story was written by Boris Durov and Stanislav Govorukhin. The film was the

lead of Soviet distribution in 1980 and had 87.6 million viewers.

PLOT

he film begins with a convoy of military vehicles rolling into a seaport located somewhere in Middle East in the bank of Indian or Pacific Ocean and stopping near the pier where the Soviet cargo ship Nezjin is anchored. An agent of a local pharmaceutical company meets the captain of the Soviet vessel and discusses the cargo, medical opium, which is in critical demand by the hospitals of the USSR. Soon after that the pharmaceutical company agent is seen inside a car, speaking to someone via walkie-talkie. Later the MV Nezjin, with the opium on board, leaves port for Vladivostok.

Some distance into the voyage, a watchman cries "man overboard" and the captain orders the engines stopped to rescue the stranded swimmer. The boat from Nezjin picks up an Asian man who identifies himself as Salikh, the only surviving sailor from a foreign merchant ship. Salikh told the crew that his ship suddenly capsized during a heavy storm and his crewmates were fighting for places in rescue boats. Shortly after that the Soviet captain is informed of an unknown ship, drifting nearby. The ship, called the Mercury, is apparently abandoned, with no crew visible and no activity on deck. The captain of the Nezjin decides to send four men to explore the ship and offer assistance to possible survivors.

However, the abandoned ship turns out to be a trap for the Soviets. Occupied with the Mercury, none of the Russian crewmen pays any attention to Salikh, who takes an axe from the ship's firefighting kit, enters the radio room of the Nezjin, and attacks a radio operator, killing him. After Salikh destroys the ship's radio equipment, the Mercury starts her engines and approaches the Nezjin. At that moment, the Nezjin's crew see the bodies of the boarding party, floating in the water behind the Mercury. The Soviet captain realizes that his ship is under attack by pirates.

Their attempt to escape is foiled when the Mercury rams the ship and the pirates open fire with assault rifles and machine guns. The pirates board the Nezjin, brutally killing Russian crewmembers who fight them. Sergey, the chief-mate of the Nezjin, discovers the dead radio operator and decides to find Salikh. Chasing Salikh through the corridors of the ship, Sergey makes an attempt to stop him. Salikh shows impressive martial arts skills and quickly defeats the chief-mate. Soon after, the pirates lock the remaining Russians into crew compartments and begin to offload the opium to the Mercury. The pirate captain thanks Salikh for a successful mission and orders him to blow up the Nezjin together with her crew. The Soviets, left to die on a sinking ship, manage to escape and must fight the pirates for survival.

CAST

Nikolai Yeryomenko, Jr. as Sergej Sergejitsch (Chief Mate)

Pyotr Velyaminov as Iwan Iljitsch (Soviet Captain)

Talgat Nigmatulin as Salikh

Rein Aren as Captain of Pirates

Dilorom Kambarova as Island girl

Natalya Kharakhorina as Mascha

Dzhigangir Shakhmuradov as Noah

Yuri Kutyrev as Shweiggert

Tadeush Kasyanov as Bosun

Maya Eglite

Viktor Zhiganov

Georgi Martirosyan

Leonid Trutnev

Vladimir Yepiskoposyan

K. Aminov

LINKS

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pirates_of_the_20th_Century

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Hijacking

http://ahijacking.com/

http://junkee.com/captain-phillips-a-hijacking-and-cinemas-somali-pirates-moment/21983

http://uk.eonline.com/news/468750/captain-phillips-reviews-are-in-tom-hanks-in-top-form-with-hijacking-thriller

http://edition.cnn.com/2013/10/08/showbiz/captain-phillips-movie-controversy/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Captain_Phillips_(film)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maersk_Alabama_hijacking

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1535109/

http://www.thesundaily.my/news/852975

http://uknato.fco.gov.uk/en/business-opportunities/020-Agencies/

http://www.act.nato.int/

http://aco.nato.int/page272201419.aspx

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Ocean_Shield

http://www.un.org

United Nations

http://europa.eu

European Union

http://www.osce.org Organization for Security and

Co-operation in Europe

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2216240/

http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/a_hijacking/

|

Captain

Phillips & A Hijacking - Youtube

|

A Hijacking (Danish:

Kapringen) is a 2012 Danish thriller film written and directed by Tobias Lindholm.

The cargo ship MV Rozen is heading for harbour when it is hijacked by Somali pirates in the Indian Ocean. Amongst the men on board are the ship's cook Mikkel (Pilou Asbæk) and the engineer Jan (Roland Møller), who along with the rest of the seamen are taken hostage in a cynical game of life and death. With the demand for a ransom of millions of dollars a psychological drama unfolds between the CEO of the shipping company (Søren Malling) and the Somali pirates.

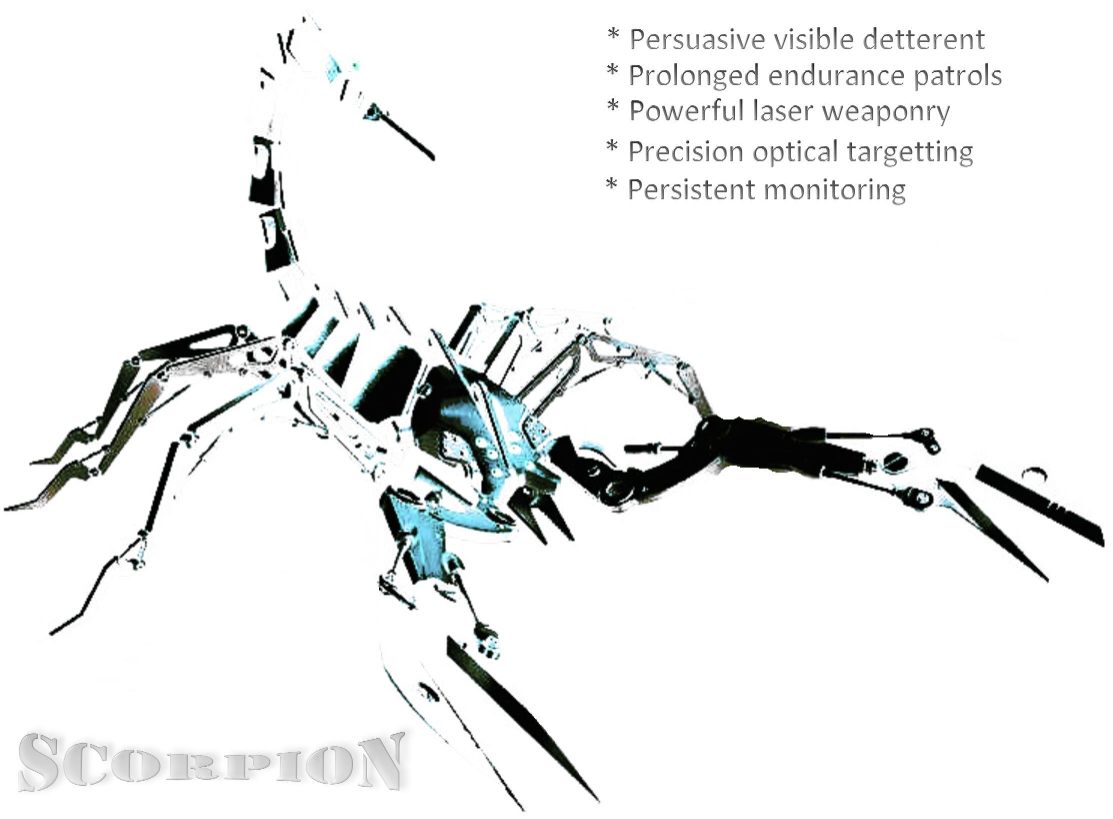

Enquiries

about the Scorpion ZCC should be directed to:-

The

Contracts Manager

BLUEBIRD

MARINE SYSTEMS LTD

Solar

House, Herstmonceux

BN27

1RF, United Kingdom

Email:

Contact: bluefish@bluebird-electric.net

PATENT

PENDING - The

ultimate Robot Boat. The SNAV platform uses an advanced SWASH

hull to

mount the world's first proposed autonomous endurance expedition. The

vessel concept is ideal for oceanographic and law enforcement applications, such

as piracy. A variety of measures are possible to quell pirates intent on

boarding a vessel, to include non-lethal lasers, electrical stunning and

water canons. Should that not be enough to prevent continued

aggression, close quarter weapons and short range missiles may be

deployed with the vessel operating in drone mode. A by product is safer

at seas derived from the COREGs

compliant Super-AIS

collision avoidance system (CAS) that the group are looking to certify

with the IMO

should that opportunity present.

|