|

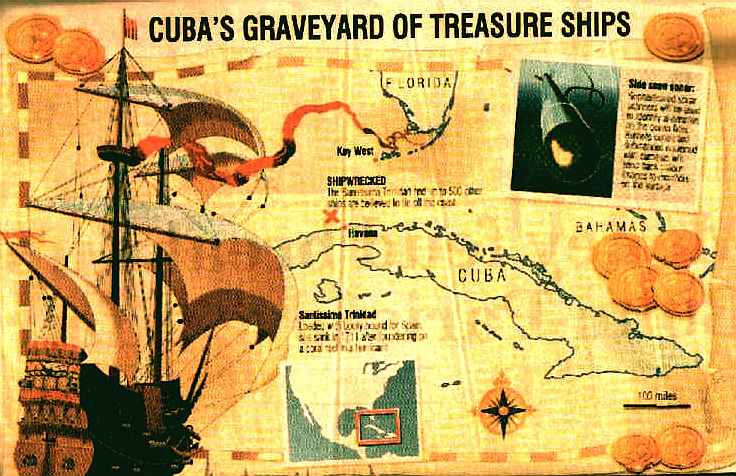

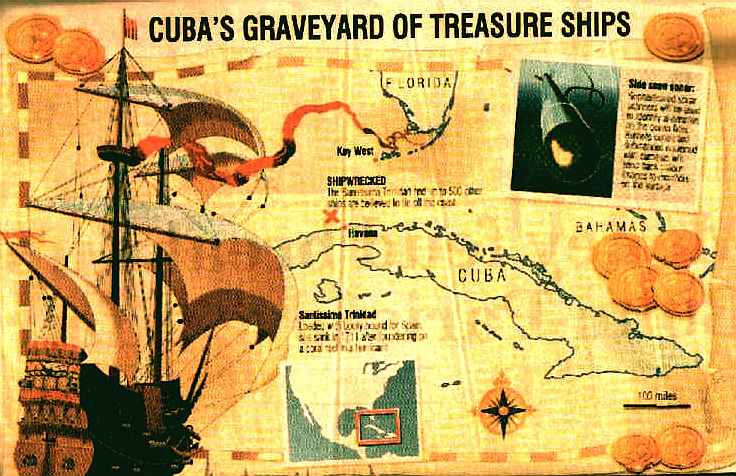

Treasure

map published in the Times newspaper

Before

we start this story, you should know that the seafloor of the

Mediterranean covers nearly a million square miles and is said to contain as many as 300,000 wrecks.

It's a similar situation to the English Channel. Ships are being found all

the time because of new technology and dedicated treasure hunters. One of

the latest finds is a silver ingot, thought to be part of Captain

Kidd's haul.

HMS

SUSSEX

HMS Sussex was an 80-gun third-rate ship of the line of the English

Royal Navy, lost in a severe storm on 1 March 1694 off Gibraltar. On board were possibly 10 tons of

gold coins. This could now be worth more than $500 million, including the bullion and antiquity values, making it one of the most valuable wrecks ever.

HMS Sussex was launched at Chatham Dockyard on 11 April 1693, and was the pride of the Royal Navy. As the flagship of Admiral Sir Francis Wheler, she set sail from Portsmouth on 27 December 1693, escorting a fleet of 48 warships and 166 merchant ships to the Mediterranean.

'Nov. 22. Kensington. Instructions for Sir Francis Wheler, knight, commander-in-chief of a squadron fitted out for the Straits. As soon as you join the Spanish armada, pursuant to the instructions of the Lords of the Admiralty, you shall act as most advisable for the annoying of the French, and shall give the Duke of Savoy notice of your arrival in the Mediterranean; and in case he desire your co-operation in any design against the French, you shall use your best endeavours to bring the same to a happy issue. During your stay in the Mediterranean you are to correspond as frequently as you can with Viscount Galway, our envoy extraordinary to the Duke of Savoy; and, as far as may be consistent with the service you are employed in, to act according to the advices you shall receive from him.'

After a short stopover in Cadiz, the fleet entered the Mediterranean. On 27 February a violent storm hit the flotilla near the Strait of Gibraltar and in the early morning of the third day, HMS Sussex sank. All but two "Turks" of the 500 crew on board drowned, including Admiral Wheler, whose body, legend has it, was found on the eastern shore of the rock of Gibraltar in his night-shirt.

Due to the extent of the fatalities, it was not possible to establish the exact cause of the disaster, but it has been noted that 'the disaster seemed to confirm suspicions already voiced about the inherent instability of 80-gun ships with only two decks, such as the Sussex, and a third deck would be added for new ships of this armament.'

Besides HMS Sussex, 12 other ships of the fleet sank. There were approximately 1,200 casualties in total, in what remains one of the worst

natural disasters in the history of the Royal Navy.

DATE

OF SINKING

In 1694 there were 10 days’ difference between the calendars of Spain and Great Britain. By “Old Style” (Julian) reckoning, Sussex

was lost on February 19, 1693/94. By the “New Style” (Gregorian) calendar, the loss was March 1, 1694. One peculiarity of the Julian calendar was that the New Year started on March 25,

rather than the January 1 of the Gregorian calendar. It was the custom when writing dates for December through March in the

Julian calendar to use a combination of years – when Sussex sank, the reports about her loss were dated 1693/94.

On the afternoon of February 17th Admiral Wheeler’s fleet weighed

anchor from Gibraltar Bay with merchant ships to sail in convoy. An eyewitness estimated that a tota l of “85 sail” or vessels departed Gibraltar. Soon after the convoy cleared the bay,

a storm blew from the southeast off the African coast, increasing in strength until it reached a full gale. The convoy, and

Sussex, were caught in the open sea and fought their way through the storm but made little progress. Early on the morning of February 19, 1694, HMS Sussex sank. A total of 560 crew including Admiral Wheeler were lost. The only survivors were two “Moors” who leaped overboard just before the sinking. The Admiral’s body

washed up on shore shortly thereafter. Wheeler’s preserved remains were returned to England for burial. The Levant Company agent, writing a personal report on the disaster, commented that the

money he placed aboard Sussex “was lost with the shippe.”

Thirteen ships of the fleet were lost in the storm. A smaller third-rate warship sailing with HMS Sussex was driven ashore and broke up. A fifth-rate warship armed with much lighter cannon than

HMS Sussex was wrecked on the shore, and a bomb ship, two armed ketches, three Dutch warships and

four armed merchantmen were also lost. The ships were widely scattered and the locations of

their sinking similarly widespread, from off the North African coast to the shores of Gibraltar and Spain. HMS Sussex was the largest and most heavily armed of all the ships that foundered in the open sea.

Witnesses to the sinking of HMS Sussex later testified at a hearing held by the Royal Navy, while the

Fleet Secretary reported a specific location of the loss of the ship . The Secretary had been left on shore in Gibraltar when Wheeler sailed, and collected local eyewitness reports for his letter to the Court. Logs of several ships of the fleet reported specific navigational fixes during a period shortly before HMS Sussex sank. Two vessels actually witnessed the sinking of the flagship and reported the

loss in their logs. All this data has been analyzed in the search for the Sussex and to assist in identification of the wreck Site.

TREASURE HUNT

The richest shipwreck in history has been sitting beneath a half mile of ocean for 300 years.

Between 1998 and 2001, the American Company Odyssey Marine Exploration searched for the Sussex and claimed that it had located the shipwreck at a depth of 800 metres.

In October 2002, Odyssey agreed to a deal with the ship's rightful owner, the British government, on a formula for sharing any potential spoils. Odyssey would get 80 percent of the proceeds up to $45 million, 50 percent from $45 million to

$500 million and 40 percent above $500 million. The British government would get the rest.

The Americans were then poised to start the excavation in 2003, but it was delayed amid a raft of complaints from some archaeological quarters, denouncing it as a dangerous precedent for the "ransacking" of shipwrecks by private firms under the aegis of archaeological research.

Just as Odyssey was about to start an excavation, it was stopped by the Spanish authorities, in particular the government of Andalusia in January 2006. In early June 2006, Odyssey provided clarification on all points to the Kingdom of Spain's Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the offices of the Embassy of the

United

Kingdom. Odyssey waited for final comments on the plan before resuming operations on the shipwreck believed to be HMS Sussex.

In March 2007, Andalusia gave her assent for the excavation to start with the condition that Spanish archeologists would take part in the excavation in order to ascertain that the shipwreck to be excavated is indeed the Sussex and not a

Spanish galleon. On the same day, Odyssey Marine sent one of its survey vessels from Gibraltar, west of Cadiz to begin its Black Swan Project, which

resulted in Spain taking various actions against the company and canceling

its agreement to cooperate on the Sussex project.

That

seems rather a shame and may contravene international law, in that the

wreckage undoubtedly belonged to the English Crown, and for sure if the

wreck proved to be Spanish, then surely the Archaeologists would advise

Spain and either then assist a survey, or leave the Andalusians to their

studies.

ARCHAEOLOGY

AND THE LAW

Research indicates that when HMS Sussex was lost in 1694, she carried a substantial amount of specie. As a

Royal Navy warship, the wreck of HMS Sussex and its contents remain the sovereign

property of the United Kingdom, except for the unwritten law of finders

keepers - and six years to a possessory title.

Today, the Site is an element of the UK’s and the world’s archaeological heritage that should be conserved (IFA Code of Conduct Principle 2). Because it lies in waters protected only by relatively untested customary international law, it is unrealistic to assume that specie potentially worth hundreds of millions of dollars would be left undisturbed as technology makes the Site increasingly accessible.

Because of potential intervention by unauthorized salvors, in situ

preservation of the entire Site is not practical. The Government, in wishing to protect the Site from unscrupulous

intervention, considered it best to excavate it responsibly, in co-operation with the finder and to the fullest extent in accordance with appropriate archaeological practice. Recovery of the economic value of this Site presents the opportunity for direct benefit to the British taxpayer, as well as advances in archaeological,

historical, educational and cultural initiatives.

THE

MISSION

In 1694, the 80-gun British warship set sail for southern France loaded with as much as 3 million pounds sterling and 6 tons of gold.

This treasure was a bribe for the Duke of Savoy to keep him allied with England in its

then war against Louis XIV.

But the Duke never got his payoff, because severe gales whipped up off the north coast of

Africa taking The Sussex along with a dozen other ships in the British fleet,

to the bottom of the ocean along with its cargo and the lives of 1,200 crew

members. Thus the Duke of Savoy threw in with Louis XIV, and England's battle with

France raged for seven more years before ending in

stalemate.

THE

COUNT OF MONTE CHRISTO'S

TREASURE

The haul is estimated to be worth as much as $4 billion at auction. Unless

aliens visited the planet on some interstellar gold hunt, the treasure is sitting right where

its been for the last three hundred years, about 2,500 feet beneath the ocean's surface.

One might imagine that for treasure seekers, the Sussex is considered to

be the ultimate prize and may remain that way with 1,100 pounds per square inch of pressure and complete

darkness to protect it. No human could ever dive that deep, even with Jim,

the armored diving suit. Recovery of the bounty is thought to be a job

best suited for robots.

GREG

STEMM

We have another article about Greg Stemm on this site which is just as

interesting. Greg is a 50 ish 21st-century treasure hunter, the found of

Odysey Marine Exploration. He's a cautious man, who'd been researching the Sussex for two

decades.

He'd

planned to send down a remote-operated vehicle (ROV) about the size of a

Vauxhall Astra down. He is quoted as saying:

"Our research makes a case that this could be the richest shipwreck in history,"

Mr

Stemm has a database of 3,000 deepwater wrecks, three side-scan sonar mapping devices, and a fleet of ROVs designed to scout

for and recover anything from a tea cup to a safe load of gold coins. Of

course they didn't have steel safes in those days - hence the proverbial

wooden chest bound with iron or brass reinforcement straps.

Gregg is a slim man with a speckled gray beard, at home in his National

Geographic cap. He is not the swashbuckling explorer variety, more down to

earth business man. Actually, he's quite knowledgeable about shipwreck history but would rather

calculate risk reduction strategy and amortize costs. Of course, he plans to use

his skills for the good of society - and to earn a himself and his

investors a bob or two in the process. In 2005 Odyssey had 15 projects on the books

that were deemed worthwhile, each estimated to be worth at least $50

million.

Such expeditions are $dollar driven. The Odyssey company is based in Tampa,

Florida. They only work in deep water and that puts potential expeditions into two

categories:-

1.

Worth it

2.

Or not.

To make the

grade, a wreck must meet three basic criteria:-

A.

Are the goods valuable enough to justify the expense of recovery?

B.

Can it be found?

C.

Will the company be able to keep the goods it recovers?

Treasure hunters rely on recovered journals and ship logs as well as tips from

local fishermen. Research the history first, then take your best guess

before filling up with diesel. Anyone with a passing knowledge of shipwrecks and a

dream of running their hands through a chest of jewels and doubloons knows roughly where the Sussex went down.

Just searching for a wreck

in a traditional diesel

powered vessel costs $100 or more per square mile. Gregg Stemm sometimes

surveys 2,000 square miles on an expedition. Coming up empty-handed after such an effort

would be a great disappointment. That's the part most adventurers don't

thank about enough.

Treasure hunting is a straightforward process. Take a boat out to a wreck

and find the loot. Simple. it gets complicated when the loot is deep down.

See John Wayne and the Wreck of the Sea Witch.

The biggest advance in modern treasure hunting is in mapping. A tow-fish dragged off the back of

a boat bathes the seafloor in sonar waves, translating the reflected data into a topographical map.

A tow-fish can cost $250,000 with monitoring equipment; heavy

investment. You'll need more than one such device. An EdgeTech

tow-fish covers 1,000 meters of ocean floor in one pass. High-end models used by the oil industry can scan a mile or more. And the results are incredibly precise.

The New York Office of Historic Preservation requisitioned a bathymetric survey of 140 miles of Hudson riverbed. The results were so revealing that the city refused to release them for fear of mass looting.

They identified every one of the hundreds of barges, tugboats, passenger ships, and pleasure craft that had sunk over the centuries.

A decade ago, it wasn't practical to take quality video at depth because of the limitations of transmitting it back to the ship over copper

wires. Early ROVs would snap pictures and return to the boat to develop the images,

which was very time consuming. Today's robots record HD digital video to

digital storage media, transmitted live back to the ship over fiber-optic lines.

ROVs have also advanced. Treasure hunting benefits from robot R&D

projects funded by the government and the oil industry. Sophisticated deepwater excavator

ROVs run to $3 million to purchase outright. Such ROVs are designed to install cables and repair leaks at depth. They come with

100+ horsepower and complicated triaxial magnetometers, designed to find buried cables at great

depths. They have high-pressure water jets to cut through clay.

THE

BAVARIA

Sixty nautical miles off the coast of northern Florida,

the steamship Bavaria sunk in 1865. She was loaded with an estimated $50 million in gold and

artifacts. The Bavaria was carrying carpetbaggers from New York City to New Orleans after the Civil War when it encountered a hurricane.

The Odyssey spent the summer of 2002 mapping the 600nm area at a cost of roughly $5,000 a

day, in the process identifying 50 targets that could be the Bavaria.

The ship drags a tow-fish in sweeps like mowing a lawn. A tow-fish is a

7-foot-long steel cylinder painted bright-yellow, which dangles on a

few miles of cable.

Depending on currents,

sonar-scanning begins, say, north to south. Once an anomaly is discovered

a ship changes course and runs east to west, creating a crosshatch. Any

such survey must maintain a strict course, north then south, overlapping slightly on each pass

and not to allow the scanning device to ground. A tow-fish is neutrally buoyant

its depth is controlled by cable payout, but an unexpected ridge, or the jutting mast of a

sunken ship, can catch the unwary.

For any tech who's examining data feed on a monitor, the challenge is simply staying awake.

This is where an autonomous robot survey ship really comes into its own. Mapping occurs 24/7 until it's done. Mostly,

the seafloor scrolls by as a stream of nothing. It's like searching for

the proverbial needle in the haystack. Hunters admit they have nodded off between 3 and 5 in the

morning. A 12 hour stretch with nothing is bound to strain the human

frame.

A small wood boat appears as a jagged dot the size of a thumbnail. Anything with sharp edges or metal components,

deflect sonar waves with greater force, so shows up more clearly. An image of a battleship looks like a photo

negative as you can see from the picture.

HAVANA

From the early 16th century, when Hernan Cortes, the legendary conqueror of Mexico, pioneered the so-called silver route

across the Atlantic, Havana's deep harbor was Spain's gateway to the New World. The conquistadors of the countries two

great treasure fleets, the Tierra Firme and the Nueva Espana, put in there on their way to and from the main-land of south and

central America. Records show as many as 13,000 vessels passed through Cuba over the years. They carried the treasure

back to the Spanish port of Seville, then the world's commercial capital.

Many ships failed to complete the journey, however, falling victim to pirates, buccaneers and vicious storms. Their precious

cargoes often ended up on the sea bed. The ships that went down included the Santissima Trinidad, an Altimiranta-class galleon

armed with 60 cannon. It foundered in a hurricane in 1711, with the loss of $400m (£242m) in silver coins and other booty

bound for King Philip V of Spain.

About 400 sunken Spanish ships are believed to lie in and around Havana harbor today, with 100 more to the west. They are

thought to contain gold bullion, silver coins, ingots, gems and emerald studded jewelry worth billions of dollars. While

American salvers have methodically scoured the seabed off Florida, Cuban gunboats have kept them out of the island's waters

for four decades.

HMS

SUSSEX NEGOTIATIONS

In 1986, Stemm was looking to buy a dinner boat to take to Jamaica when he

found a research vessel for sale by the University of North Carolina. He bought

that and: "through a series of coincidences" ended up with a small ROV.

This was the beginning of Stemm becoming a treasure hunter.

Without the benefit of global positioning or satellite weather mapping systems, countless ships have gone down over the centuries.

They say that 10 percent of all ships that have ever sailed have sunk.

Odyssey's first success came soon thereafter with a 1622 Spanish wreck off Key West. Stemm broke even on the $5 million

cost to recover artifacts, pearls, and gold. This established Odyssey's credibility.

Odyssey began mapping the Spanish coast at a cost of $3 million dollars

over four years. They determined that the Sussex went down in a high-traffic shipping lane near the Strait of Gibraltar. Odyssey's sonar maps revealed 418 targets, two of which turned out to be Phoenician wrecks that dated as far back as the fourth century BC.

Stemm says: "You see a lot of geology, but then all of a sudden you could see

cannons."

According to terms agreed, the company funds the excavation at a cost of $5 million or more. In return, it gets 80 percent of the first $45 million,

then half of the next $455 million and 40 percent of everything after that. The government has first rights to buy everything. The rest

may be sold at auction, on Web sites, or to private collectors. If the bounty goes for $4

billion

Odyssey stands to make $2 billion. Critics of the Sussex arrangement say that would make Stemm

and his investors the richest pirates in history.

In a 1998 book, Ship of Gold in the Deep Blue Sea, author Gary Kinder recounts the recovery of the SS Central America, a steamship loaded with 21 tons of gold from the California Gold Rush that went down in 8,000 feet of water off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. In 1996, treasure hunter Tommy Thompson went after the Central America and brought up millions of dollars in coins by developing new methods to work at depths once considered unreachable. He then spent a dozen years and millions in legal fees battling for the right to keep

it. That makes him the poorest pirate in history. Where's Jack Sparrow

when you need him?

HOW DO YOU RECOVER $4 BILLION

It's not easy locating an almost completely eroded, 300-year-old wooden warship in total darkness a half mile below the ocean's surface. In the search for the Sussex, treasure hunter Greg Stemm and his crew mapped the seafloor off the coast of Spain, inspected hundreds of targets, and after bringing up a few cannons, believe they've identified the richest shipwreck in history.

Here's how

we suggest that you go for gold:-

1. Map the Ocean bed

First thing thing is to create a topographical map using a side scan

tow-fish to bathe the seafloor in sonar waves on a 5-mile tether. A survey

ship runs parallel tracks, overlapping slightly, a bit like mowing a lawn. The process identifies any irregularity

the size of a chair (or treasure chest) on the seafloor. The best ship for

such a mundane task is the Mosquito

version of the SNAV, equipped with the automatic launch and recovery system

for towed arrays.

2.

Inspect the Target

Once mapping of the seafloor is complete, the SNAV deploys a refrigerator-sized inspector ROV to take videos and pick up samples. The images are relayed back to the ship in real time via steel-encased fiber-optic cable and stored

on high-density external hard drives (now relatively cheap) for further study. Archaeologists

can then date the artifacts and assess their value at their leisure.

3. Raise the Titanic

Once a target has been identified, it's time for the big gun: the excavator ROV. These multimillion-dollar deepwater robots were first developed for the government,

the film

and the oil industries. For treasure recovery, operators can customize their ROVs by adding attachable arms and

elevator systems to bring up heavy items such as canons, safes and dare we

say it, treasure chests - me hearties.

LINKS

ADVENTURE

GALLEY - Captain Kidd

HANNEKE

WROMEN - 1486 gold coins

TREASURE

HUNTERS

Maritime

Professional News

Treasure

Net shipwrecks heartland treasure quest

Marine

Link academic treasure hunters

http://www.maritimeprofessional.com/News/351646.aspx

http://www.treasurenet.com/forums/shipwrecks/1062-heartland-treasure-quest.html

http://www.marinelink.com/news/academic-treasure-hunters351646.aspx

Metal-Detecting-for-Beginners

http://www.larsonjewelers.com/Metal-Detecting-for-Beginners.aspx

Wired

shipwreck

http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/11.09/shipwreck_pr.html

Brendan

Foley shipwreck seeking robots transform maritime archaeology

www.metaldetector.com/marine-salvage-search-recovery/underwater-treasure-hunting-using-rov

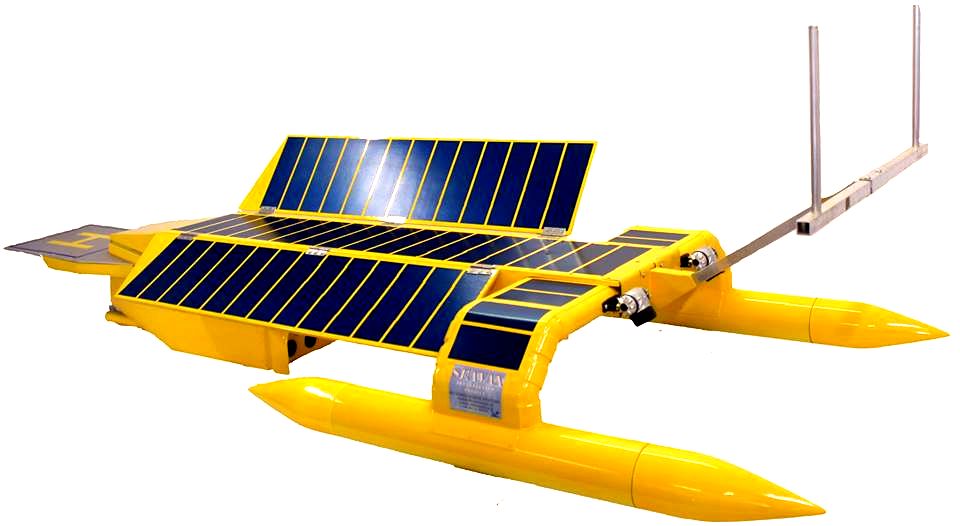

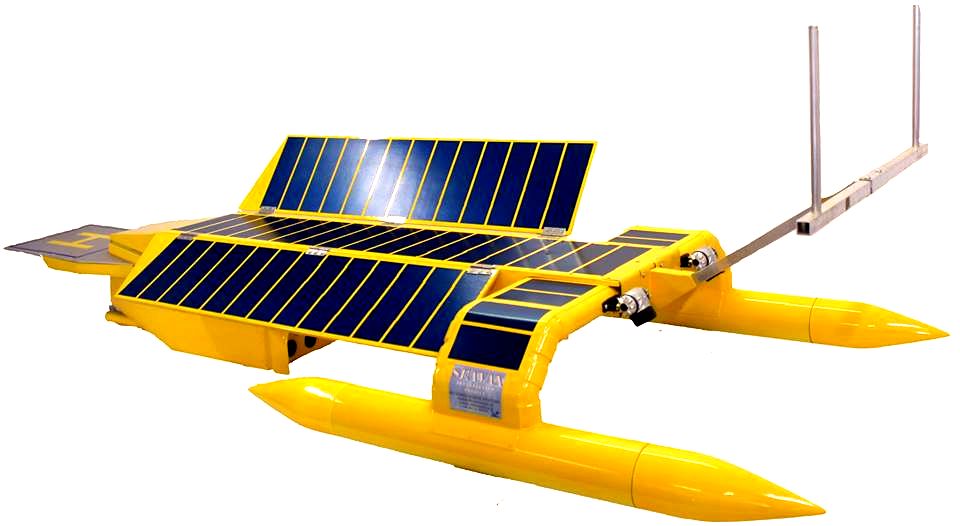

Could

this be the

ultimate Robot Treasure Hunter, the

proposed ELIZABETH SWAN marine exploration platform uses

an advanced active

hull design to provide autonomy for archaeological exploration and

other data acquisition. The boat above shares solar wings and wind

turbines as the means to propulsion.

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC - ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BERING - CARIBBEAN

- CORAL - EAST

CHINA

ENGLISH

CH - GOC - GULF MEXICO - INDIAN

- MEDITERRANEAN - NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC - PERSIAN

GULF - SEA JAPAN

STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE - UNCLOS

- UNEP

- WOC

- WWF

|