DEVELOPMENT HISTORY

Stan Sayres bought the first rig to be named SLO-MO-SHUN in 1938 from Jack "Pop" Cooper of St. Louis, Missouri, a famous Mid-West race driver. The former TOPS II, SLO-MO-SHUN I was a Ventnor 225 Cubic Inch Class hydroplane that threw a connecting rod,

caught fire, burned, and sank in Lake Washington in 1941. The boat was a total

loss.

Sayres acquired a second Ventnor 225, the TOPS III, from Cooper in 1942. One sponson of SLO-MO-SHUN II was damaged in transit, as the story goes, and Sayres asked Ted Jones, who had been building and racing boats since 1927, to help true up the new sponson. It was at this time that Jones informed Sayres that he had the working design for an extremely fast boat and was seeking a backer.

After World War II, Sayres commissioned Jones to build the 225 Class SLO-MO-SHUN III. Jones, a Boeing Company employee, did so initially in the basement of his own home and later at the Jensen Motor Boat Company in 1947. SLO-MO-SHUN III was similar to other boats that Jones had constructed in recent years but was built heavier to withstand rough usage.

Sayres and Jones discovered that the "III" was capable of speeds almost 10 miles per hour faster than others in its class at the time. She was not campaigned all that extensively due to a lack of local competition, and because her makers were already planning a larger and more powerful boat.

Sayres, Jones, and Jensen attended the 1948 APBA Gold Cup in Detroit. After sizing up the situation there, Jensen recommended to Sayres that they build a boat along the lines of MY SWEETIE, which was a non-propriding two-step hydroplane, designed by John Hacker. But Sayres accepted Jones's suggestion that SLO-MO-SHUN IV should be a three-point proprider.

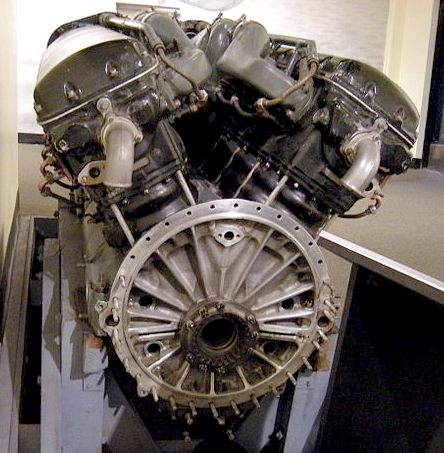

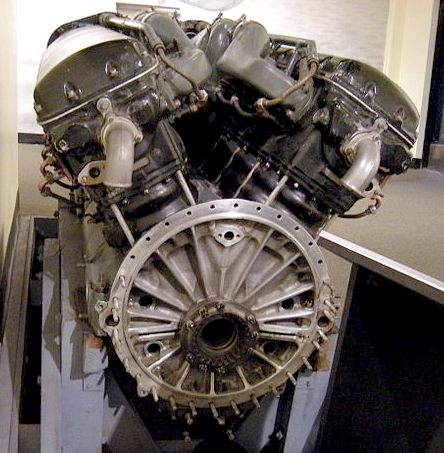

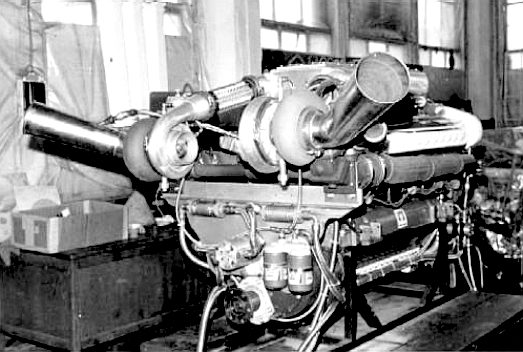

The Allison V-1710-C first flew on 14 December 1936, the result of sporadic US Navy and Army funding. The V-1710-C6 successfully completed the US Army 150 hour Type Test on 23 April 1937, at 1,000 hp (750 kW), the first engine of any type to do so. By then all of the other Army engine projects had been cancelled or withdrawn, leaving the V-1710 as the only modern design available. It was soon found as the primary power plant of the new generation of United States Army Air Corps

(USAAC) fighters, the P-38 Lightning, P-39 Airacobra and P-40 Warhawk. That was until the Rolls Royce Merlin engine was found to be superior at high altitude

using a

supercharger, and was fitted to the P-51 Mustang (above

right), making the Allison unit all but redundant.

Slo-Mo-Shun’s 1500-horsepower Allison aircraft engine drives the propeller, through gears, at about 10,000 revolutions per minute. The step-up gearbox is bolted directly to the rear of the engine, permitting the use of a short, straight, drive shaft instead of the customary transfer drive from the bow. The deep steel rudder is mounted off center so that it moves in undisturbed water instead of in the frothy wake of the propeller.

CONSTRUCTION

Construction of SLO-MO commenced at the Jensen Motor Boat Company in the fall of 1948, following the basic design that Jones had envisioned ten years earlier.

Anchor Jensen, who had never before built a race boat, was in charge of construction and did much of the work himself.

L.N. "Mike" Welsch, who worked with Jones at Boeing, became the "IV's" crew chief. "The boat was good from the beginning," Welsch told interviewer David Greene, "although we did modify the steering and change the

rudder location."

A public subscription drive in the Seattle area enabled SLO-MO-SHUN IV's entry in the Gold Cup race on the Detroit River. Then, as now, the Gold Cup stood as the ultimate power boating

prize - the World Series, the Super Bowl, the Kentucky Derby, and the Indy 500, all rolled into one aqua-carnival of speed.

Upon arrival in the Motor City, then the hub of organized boat racing in North

America, the oddsmakers conceded that SLO-MO was indeed an awesome sight to behold on the straightaways with that impressive roostertail of spray a

football field in length. They doubted, though, the recordholder's ability to effectively corner under competitive conditions and labeled her "A worm in the turn."

This notion vanished quickly when pilot Jones made several high-speed test laps around the 3-mile Detroit River race course and demonstrated that cornering was not a problem.

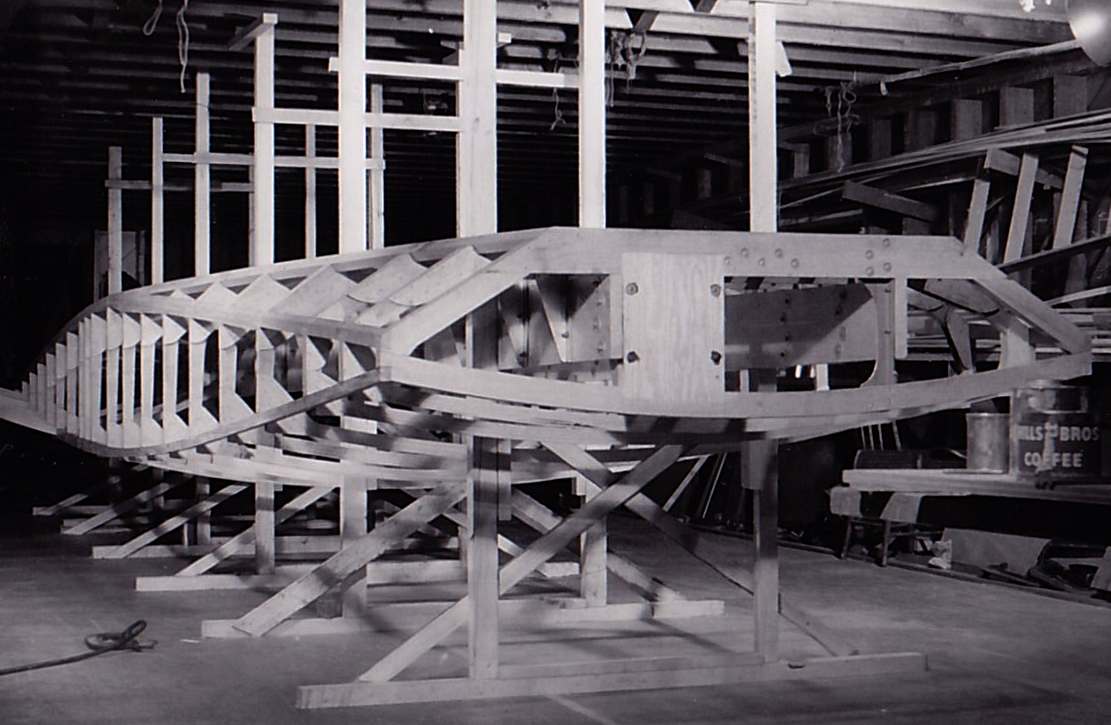

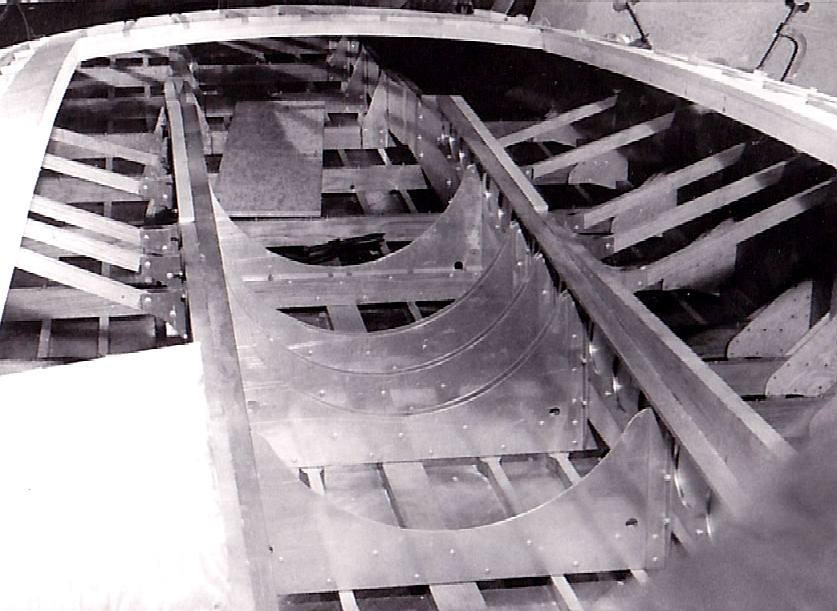

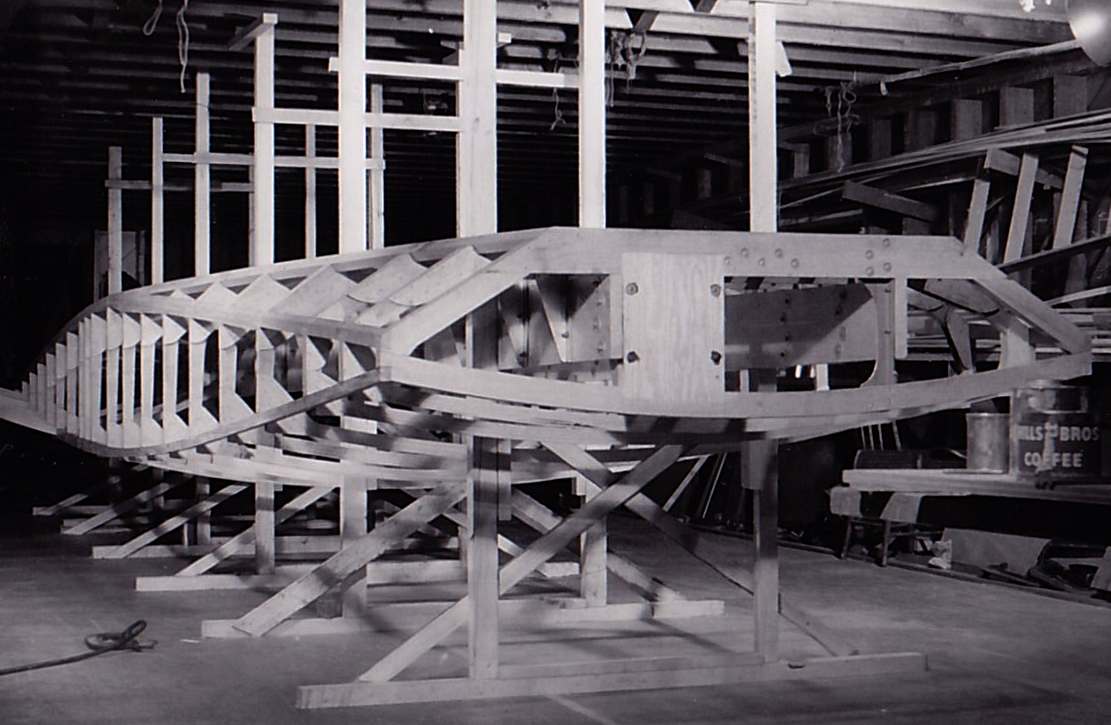

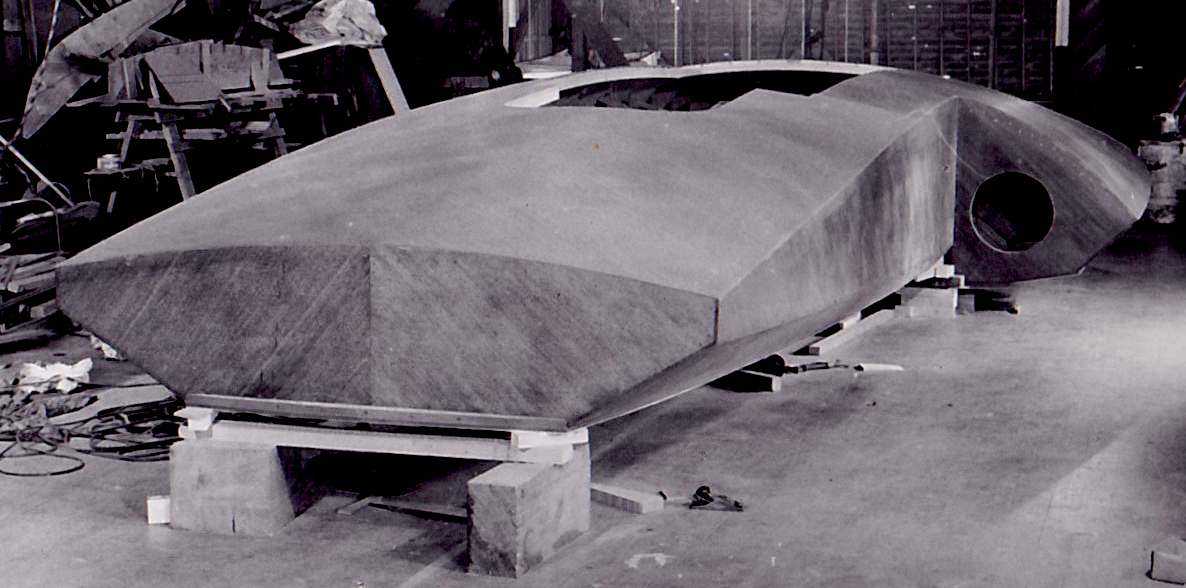

Inverted,

the boat is built upside down, with the hull topside. Note the

cross-braced frames that are supporting the hull while it is being made.

It is important to get these frames absolutely square and level before

proceeding.

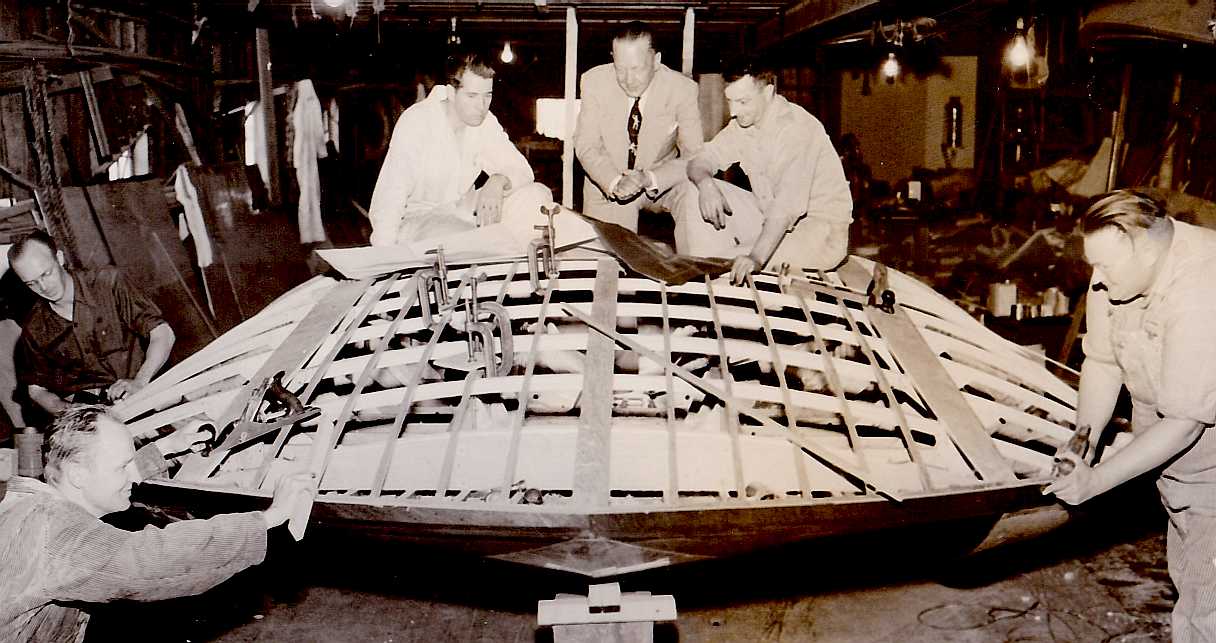

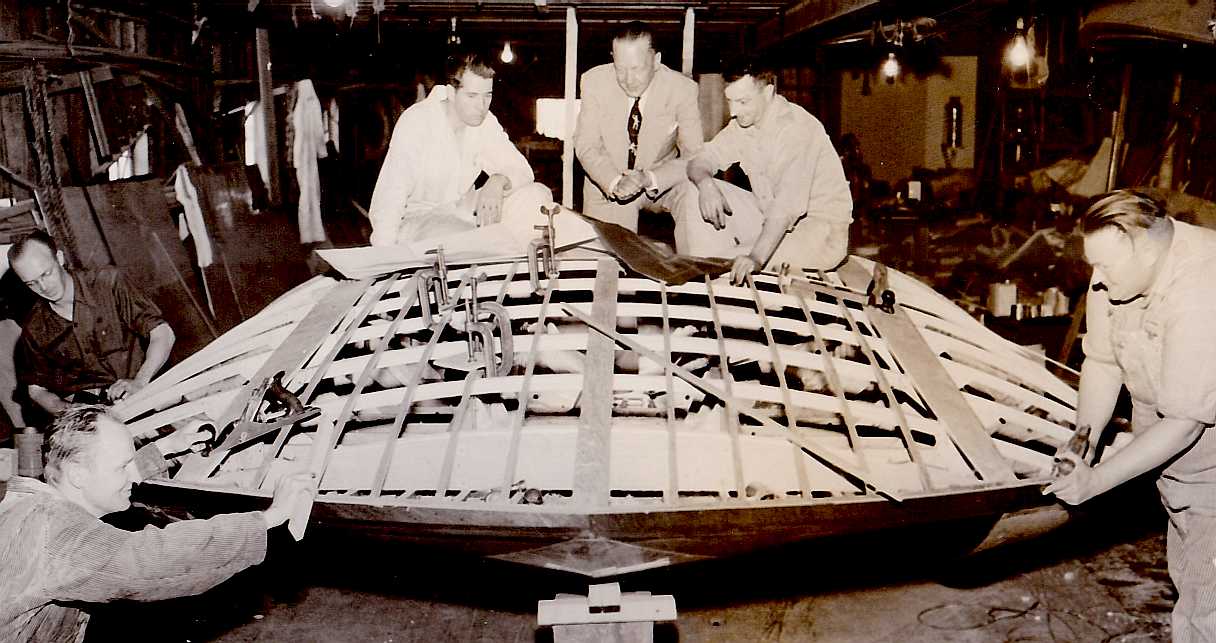

Many

hands make light work. As soon as the boys knew there was a camera in

the workshop, they all came a running. Even the boss, Stan Sayers, got a

look in.

In those days, the Gold Cup race site was determined by the yacht club of the winning boat rather than by the present method of the city with the highest financial bid.

SLO-MO-SHUN IV won all three 30-mile heats of the 1950 contest with Ted Jones driving. In the first heat of the day, Slo-mo lapped the entire field, which included the 1949 Gold Cup winner MY SWEETIE.

Not once in the 46-year history of the event had the Gold Cup winner hailed from any other locale farther west than Minneapolis (in 1916). Immediately, Sayres announced plans to defend the cup on his home waters of Lake Washington.

Before concluding her maiden year of competition, SLO-MO-SHUN IV also claimed first-place in the Harmsworth International Trophy race in Detroit. Driven this time by Lou Fageol of Kent, Ohio, the "IV" became the first craft in history to be timed at 100 miles per hour in a heat of competition around a closed

(5 nautical mile) course.

SLO-MO averaged 100.680 in the second heat of the best two out of three-heat series. She thus became the first boat to win both the Harmsworth and the Gold Cup races, in addition to setting a world straightaway record, during the same calendar year since

MISS AMERICA (in 1920).

The response of Seattleites to SLO-MO's success was, in Mike Welsch's words, "Fantastic. That was part of the enjoyment of working on the boat because of the way the public backed

us - especially the little kids, five and six years old. That was really

something - the reaction of the city - and made working for nothing fun."

Slo-Mo-Shun is rolled into the

US Naval reserve building where it finds a home

The SLO-MO-SHUN mechanical crew was more than just a racing team. It was the most exclusive men's club in the Seattle area in the 1950s. And everyone wanted to join. But very few ever achieved the inner circle. Some of those who did included Elmer Linenschmidt, Joe Schobert, George McKernan, Wes Kiesling, Pete Bertellotti, Rod Fellers, Jack Harshman, Martin Headman, Fred Hearing, Don Ibsen, Jr., Bob Stubbs, and Jack Watts.

Owner Sayres recognized that he would need a second hull in order to compete with the Detroit contingent's numerical superiority. SLO-MO-SHUN V had the same designer, builder, length, and power source as her predecessor, but had a wider beam and a slightly different sponson design that included larger non-trip areas. Unlike her sister, SLO-MO-SHUN V was built for competition rather than for straightaway performance.

For Seattle's Unlimited debut, two major races - for the Gold Cup and the Seafair

Trophy - were scheduled for consecutive weekends during the month of August, 1951. SLO-MO-SHUN V won both of them with Lou Fageol driving in the Gold Cup and Ted Jones in the Seafair Trophy. On the first lap of the initial race, Fageol demonstrated acceleration never before witnessed in competition and was credited with a 3-mile mark of 108.633, which raised the former standard by better than 22 miles per hour.

SLO-MO-SHUN IV was run under wraps during the Gold Cup, taking a safe third. She was, however, turned loose in the Seafair Trophy, which was, in effect, a match race between the "IV" and the "V." SLO-MO-SHUN V took the first and third heats; SLO-MO-SHUN IV won the middle stanza in record time for two laps around the 5-nautical mile course at 111.743. This eclipsed the former all-time high for the same distance by better than 4 miles per hour.

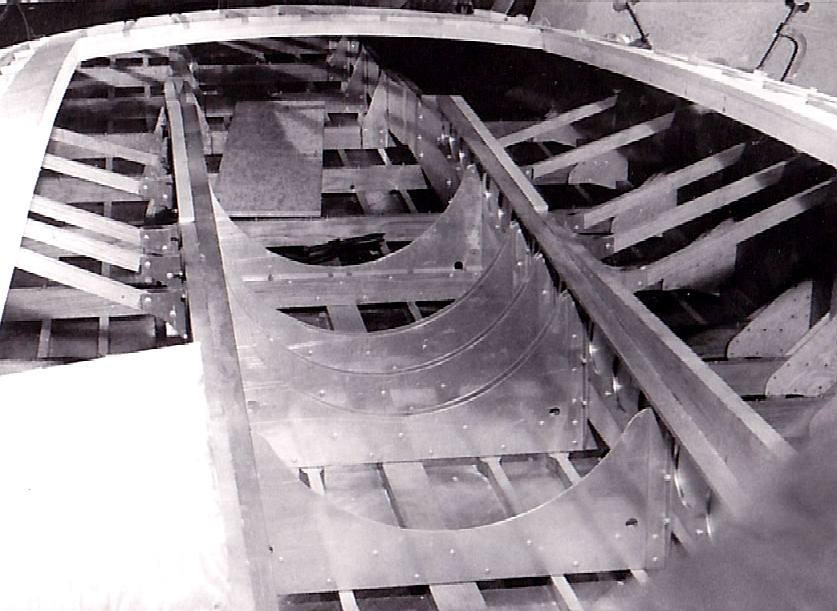

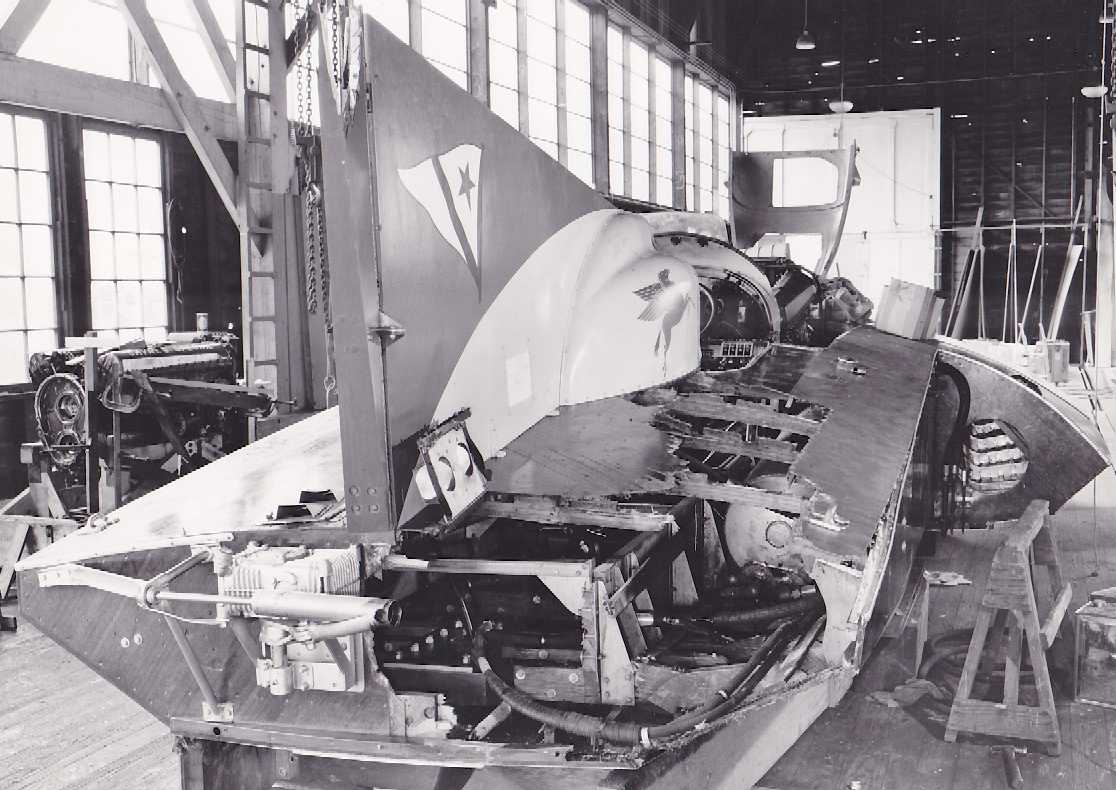

This

is the engine bay, fitted with alloy reinforcing, with cross-bracing

from the top of the main frame spars, to the underside of the deck.

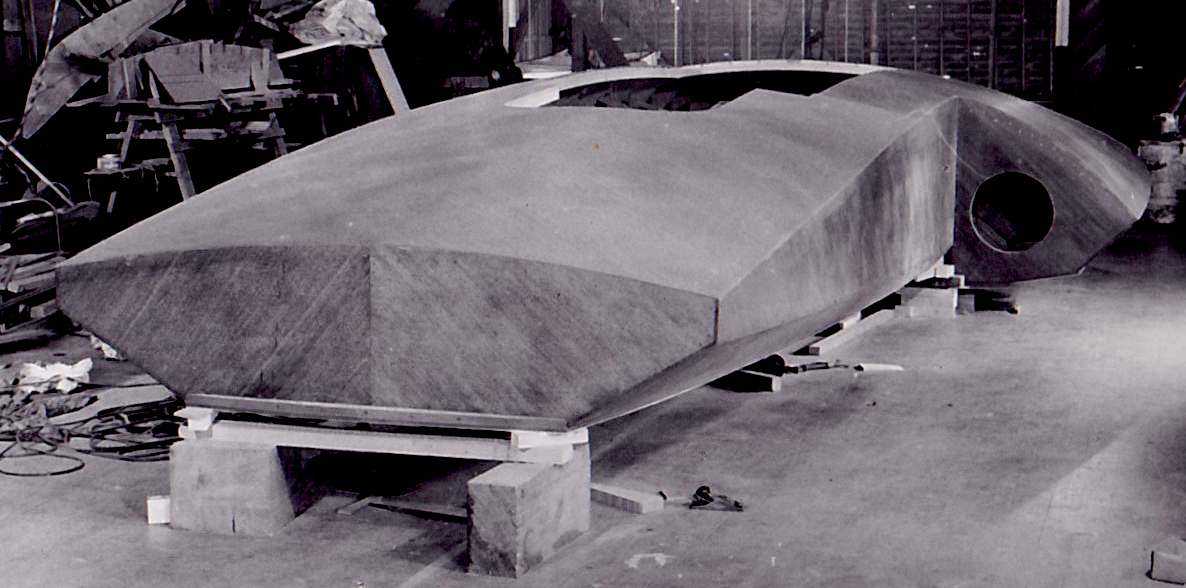

That's

looking good. The frames are now covered with marine plywood, ready for

sealing and varnishing.

LAUNCH

- The plywood hull has a ˝-inch-thick bottom that is sheathed in part with thin dural plating as a protection against floating debris. Unused portions of the hull are packed with foam plastic for floatation in case of a smash-up. The boat weighs 4300 pounds. To stabilize the hull and offset the effect of engine torque,

Slo-Mo-Shun uses a large air fin at the stern. The fin is simply a stabilizer and isn’t used for steering.

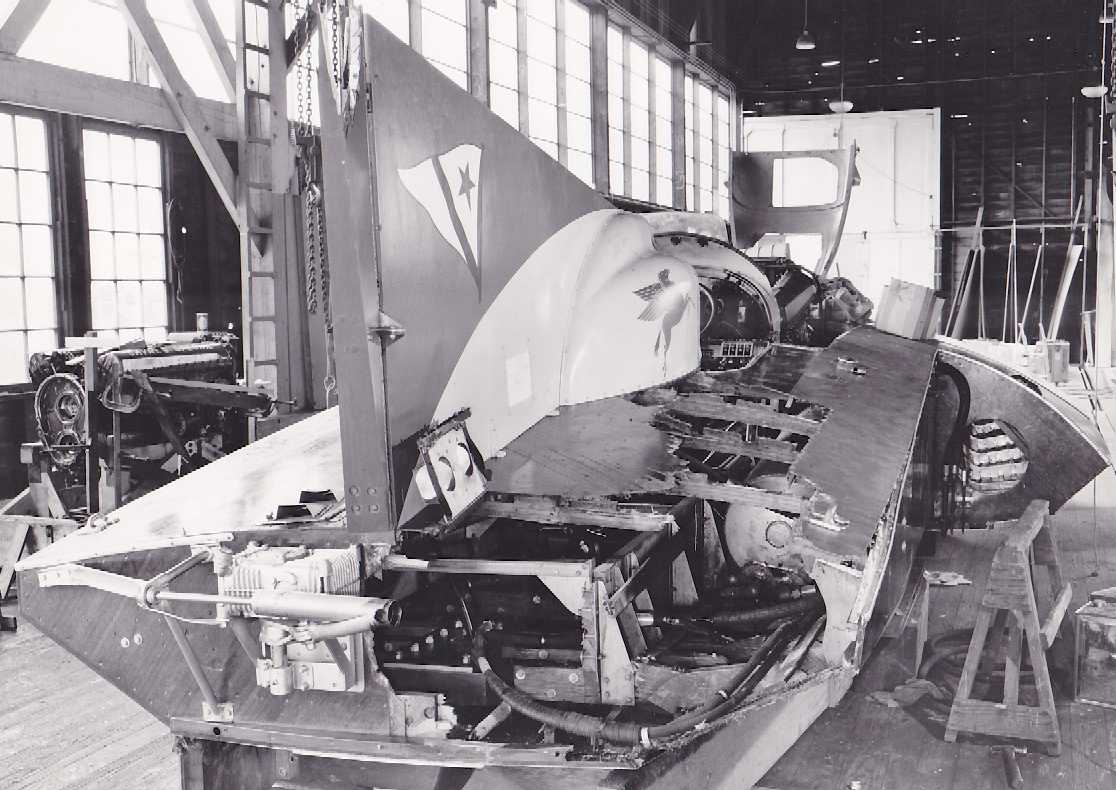

Oh

dear! Slo-Mo-Shun returns to the workshop after a scrape. The transom

has been ripped away and the decking torn apart. Must have been one hell

of a ride. The fastest boat in the world in 1951 was 28 feet long and has a beam of 11 feet 5 inches.

Following the 1951 season, Jones left the SLO-MO-SHUN team. (He re-appeared in 1954 as designer of BREATHLESS and in 1955 as designer and team manager of MISS THRIFTWAY and REBEL SUH.) After the split between Jones and Sayres, SLO-MO-SHUN V was rebuilt. The boat was still fast but experienced handling difficulties and was never quite the same.

Sayres entered SLO-MO-SHUN IV in another straightaway trial in 1952--this time on Lake Washington's East Channel near Mercer Island. He felt that the "IV" had not been run to the maximum when he did 160 with her in 1950. With Elmer Linenschmidt alongside as riding mechanic, SLO-MO IV did 178.497 over the measured mile.

In comparing the two boats, Mike Welsch felt that SLO-MO-SHUN V was quicker out of the corners. "Once she came out of the turn, V could get up and clean out faster than 'IV.'

"SLO-MO IV had a tendency to stick in the turn. You had to turn 'IV' right to break it loose before you could get going. 'V' didn't have this tendency. It had some dihedral in the side that we didn't have in the 'IV' until later, when we added a bustle. Anything over 165 mph would cause the bow in the 'V' to start kiting. It would really get hairy. The 'IV' could do 185 with no strain."

SLO-MO-SHUN IV won both of the next two Gold Cup races in Seattle. "The Grand Old Lady," as she was then labeled, took the 1952 event with Stan Dollar at the wheel and the 1953 renewal with Fageol and Joe Taggart alternating in the cockpit.

Dollar had won the 1949 Harmsworth Trophy with his Lake Tahoe, California-based SKIP-A-LONG; Taggart, from Canton, Ohio, was a champion 225 Class pilot and had debuted as an Unlimited driver in 1952 with Albin Fallon's MISS GREAT LAKES II.

SLO-MO-SHUN V experienced mechanical problems at both of the hometown races in 1952 and 1953, but took in the Eastern circuit in 1953. Fageol won the President's

Cup with the "V" on the Potomac River in Washington, D.C. SLO-MO-SHUN V was probably the fastest competitive boat in the world on smooth water but was something else on the rough Eastern courses and still needed proper trimming after three years of racing.

In 1954, SLO-MO V handed Stan Sayres an unprecedented fifth straight Gold Cup award. Instead of the tried and proven Allison, however, the "V" used a Rolls-Royce Merlin. According to Mike Welsch, "We compared the two engines and the thing that convinced us was the blower and the manifold system. The Rolls also had a very impressive front end and intake system."

The move to Merlin power was a gamble because several prominent teams had experimented with them in the 1940s and found them too temperamental to their liking. "At first, we were just going to test them to see what we had," said Welsch. "But once we tried the Rolls, there was no life in the Allison as far as we were concerned.

"After the performance in 'V,' we figured that we had better put it in 'IV,' too. And we had no trouble getting engines in those days."

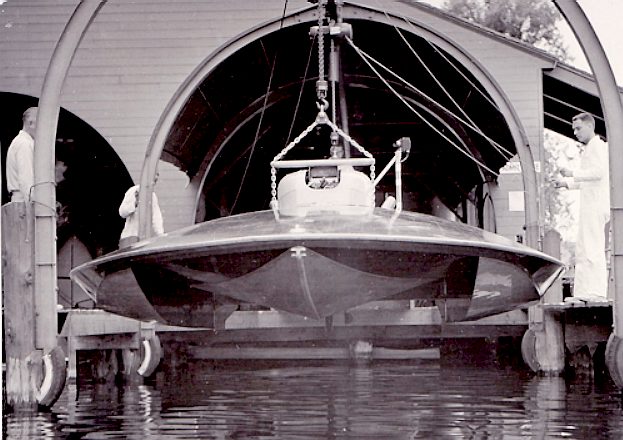

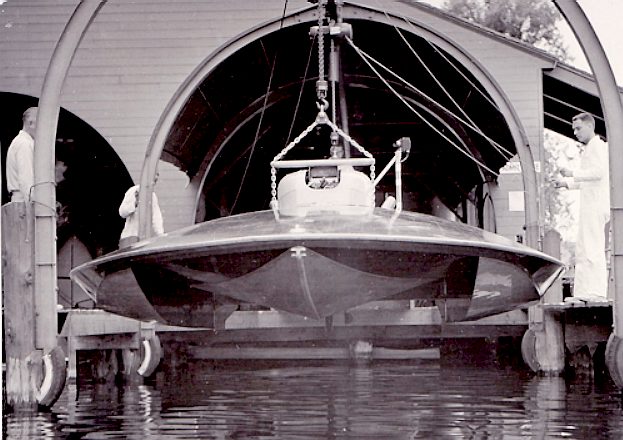

Launched

at last. The pilot cannot believe that he's being given the all clear to

rev the engine for a shake down run. Tudor Owen ("Ted") Jones (died January 9, 2000)

was the designer and builder of Slo-Mo-Shun.

Oddly enough, the Rolls-Royce

Merlin engine used in SLO-MO-SHUN V to win the 1954 Gold Cup was the same power plant used in the ill-fated QUICKSILVER, which crashed to the bottom of Lake Washington in 1951 with fatal consequences.

Lou Fageol announced his retirement from competition after the 1954 Gold Cup. Fageol mentioned the name of the future Unlimited Class superstar, Bill Muncey, to Stan Sayres as a possible replacement. Nothing came of the suggestion as Fageol returned in 1955 for what would prove to be his final appearance as a driver.

While attempting qualification at the Gold Cup in Seattle, SLO-MO-SHUN V turned a complete 360-degree backward somersault at a frightening 160 to 165 miles per hour. Fageol was on the backstretch of his third official lap on the 3.75-mile course after posting identical readings of 117.391 on the first two.

The "V" landed upright minus her pilot and coasted - remarkably intact - to a halt. Rescue teams found the stricken Fageol still conscious but badly injured, his distinguished driving

career - which dated back to 1928 - at an end.

The winner of 74 first-place trophies in boat racing, Fageol had popularized the chillingly

spectacular - and highly controversial - "flying start" from under the Lake Washington Floating Bridge in the early days of Seattle's love affair with Thunderboating.

For years, the Sayres team had yielded to civic pressure to remain active in Gold Cup competition. rather than retire undefeated. But on the eve of the 1955 Gold Cup, Stan announced that the next day's race with Taggart and SLO-MO IV would be his last. As the only five-time consecutive winning owner of that famous cup, he would give it one last try. And he nearly pulled it off.

The "IV" was leading and only three laps from victory when the manifold started to crack. Taggart eased off to nurse "The Old Lady" along. With two laps remaining, the SLO-MO driver elected to save the boat and himself from fire, which had spread to the hull, and shut off the engine, forever dashing the team's hopes for a sixth consecutive triumph in the race of races.

One can only speculate as to what effect the running of several additional hard

laps - due to an Official's error - in the confused first heat of the day, may have had on the hometown favorite's inability to finish the grueling 90-mile grind.

Although "retired," Stan Sayres and his crew continued to test SLO-MO IV the following winter as they had in the past. Sayres sold the disabled SLO-MO V to a local syndicate, which repaired and renamed her MISS SEATTLE. The former "V" raced off and on between 1956 and 1966 but was never again the contender that she had been as SLO-MO-SHUN V.

One week before the 1956 Seafair Trophy Regatta on Lake Washington, Sayres announced that he would return for at least one more event. The "IV" ran an extremely competitive race. She tied the winner, SHANTY I, another Ted Jones hull, on points but not on elapsed time. SLO-MO was decisively beaten in the Final Heat showdown, but had managed to defeat SHANTY I in an earlier preliminary skirmish.

The "IV" was obviously not yet ready for the bone yard, and the Sayres team elected to send her to Detroit for one last try at the Gold Cup, which had been captured the previous year by the Motor City's GALE V.

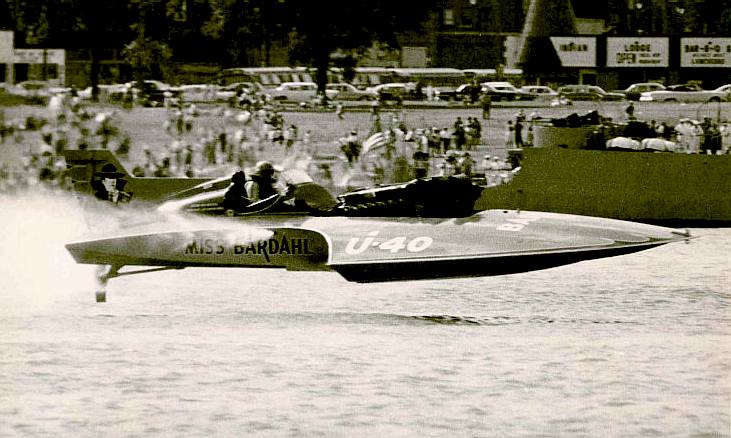

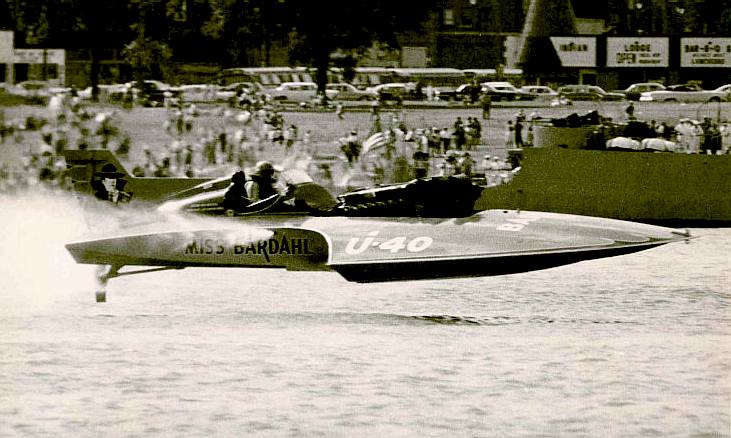

Miss Bardahl was the third of five boats that

Ole Bardahl built (Bardahl Oil Co). She raced from 1962 through 1965, making her the first boat in 30 years to win three consecutive

Gold Cups.

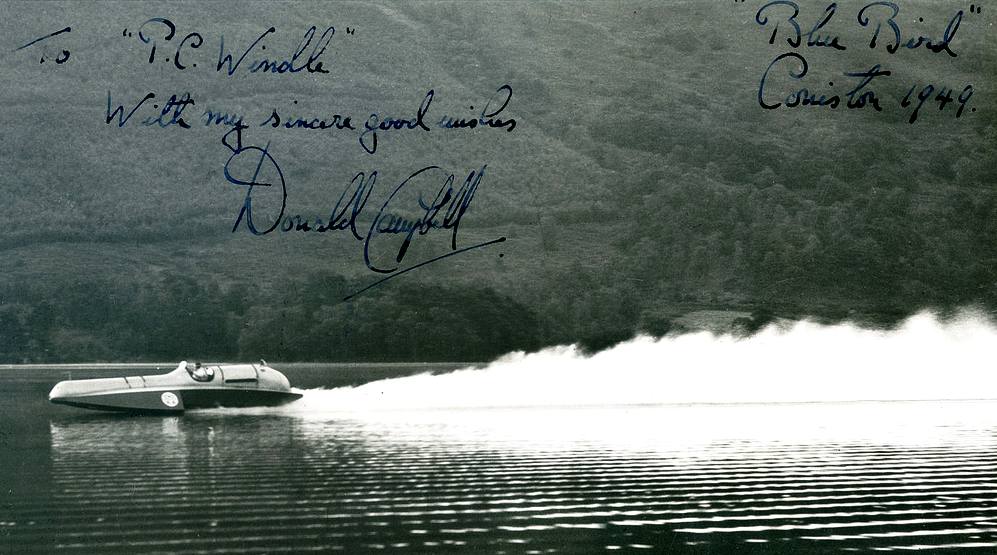

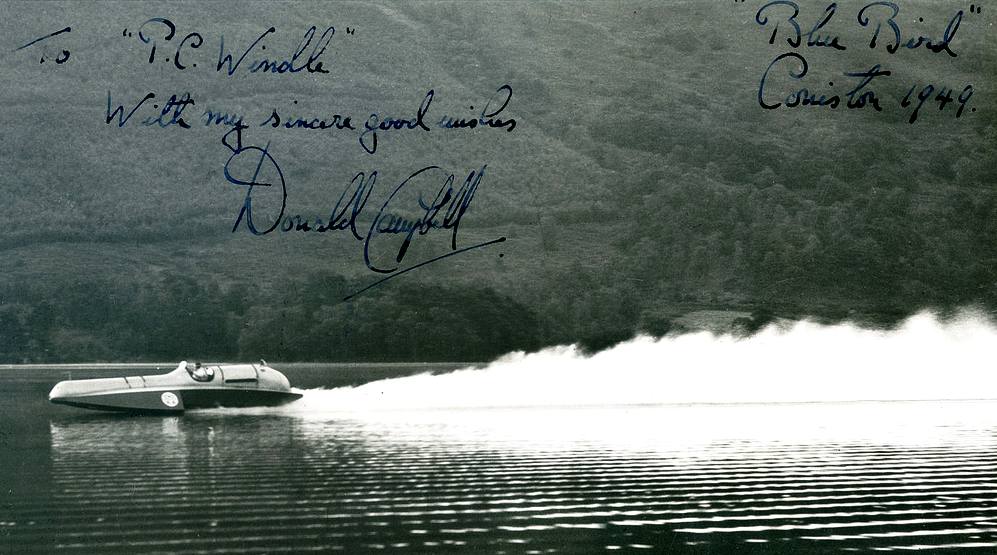

If

only Donald

Campbell's K7

Bluebird had been designed with this perfect balance, then there

would have been less chance of the flip that proved fatal. To be even

more certain of airborne stability, we'd suggest fitting additional air

control devices to craft that are expected to exceed 300mph. See Ken

Warby's Spirit of Australia.

CRASH

On an early August morning, a radio report broke the sad news to Seattleites that their boat had crashed during a trial run on the Detroit River. At 150 miles per hour, SLO-MO-SHUN IV had encountered the wake of an illegally moving patrol boat and broken apart, inflicting serious injuries on Joe Taggart,

who - like Fageol before him - would never race again.

Sorrowful over the misfortune to his boat and driver, Stan Sayres refused to even look at SLO-MO-SHUN IV in her wrecked state. He died in his sleep three weeks later, a truly heartbroken man.

Sayres did, however, leave a final legacy to the sport that he loved, in the form of an offer to HAWAII KAI III owner Edgar Kaiser, who had assisted in transporting SLO-MO to Detroit. Sayres made available his spare

Rolls-Royce Merlin engine for use in the KAI, together with his experienced crew to maintain it.

Beginning with the 1956 President's Cup Regatta, the entire team would affiliate with "The Pink Lady" HAWAII KAI III, which, for the next two years, would fill the void as the sympathetic successor to SLO-MO-SHUN IV as far as Seattle fans were concerned. Backed by the SLO-MO crew, HAWAII KAI won eight

races - six of them consecutively - and hauled down the 1957 National Championship in addition to upping the mile straightaway record to 187.627 with Jack Regas as driver.

In 1957, the new hydroplane pit area on Lake Washington boulevard was dedicated to the memory of Stan Sayres. And, in 1990, the Seattle race course was dedicated to Ted Jones by a grateful Unlimited hydroplane fraternity. Sayres and Jones were the two men most directly responsible for the SLO-MO legend and for introducing the Pacific Northwest to big-time power boat racing.

The battered hulk of SLO-MO-SHUN IV was eventually restored for display by original builder Anchor Jensen and donated to the Seattle Museum Of History And Industry in 1959.

During the decade of the 1990s, both SLO-MO-SHUN IV and SLO-MO-SHUN V were put back in running condition by the staff of the Hydroplane And Raceboat

Museum in Seattle, headed by Dr. Ken Muscatel.

In June 1999, SLO-MO-SHUN IV re-enacted her 1950 mile trial at Sand Point in tribute to the 50th year of the Seafair civic celebration with Dr. Muscatel driving.

The boat's designer and builder Jones and Jensen were on hand to witness the latest chapter of the ongoing SLO-MO-SHUN saga.

Some

great scale model making, the method of construction not that far

removed from the real boat, save that the full size version needs many

times more the stringers and frames as you can see from the pictures

above. Making models sets you

up for making larger craft. It's much nicer to learn the trade at a

small scale, when materials are not expensive.

STANLEY SAYERS

Stanley S. Sayres (1896-1956), the owner and driver of the hydroplane, moved to King County in 1932. He was in the automobile business heading the American Automobile Company, a

Chrysler car dealership at 1001 Broadway in Seattle, and an auto parts store in the University District. Sayres also owned the Jen-Cel-Lite Corporation, a manufacturer of cold weather clothes.

He became interested in speedboat racing in 1926 in Oregon, and his interest continued after he moved to King County, Washington. In 1949, Sayres built a 17-room home on the east side of Hunts Point near the point's north end (4450 Hunts Point Road), along with a boathouse for his hydroplanes. Hunts Point is on the east side of Lake Washington.

Sayres had owned and raced smaller boats, but he wanted to try for a world record. With this in mind, he commissioned Ted Jones to design the Slo-mo-shun IV and Jensen Motor Boat Company, at the north end of Seattle's Lake Union, to construct it. Jensen Motor Boat Company launched the 28-foot-long, 4,750-pound hydroplane in October 1949.

A PERFECT DAY FOR SPEED

From June 21 to 23, 1950, due to rough water and a broken propeller, Sayres's first attempts at world record runs failed. But in the early morning hours of June 26, lake conditions, with a light chop on the water, were perfect for speed. At 5:30 a.m. boats went out along the measured one-mile course and picked up any debris they could find. At about 6:45 the course was ready and the Slo-mo-shun IV, with Sayres and crewmember Ted Jones, headed out.

On the first attempt, the timer malfunctioned. The Slo-mo-shun IV continued to the south end of the course, and turned north. Sayres opened the throttle, and the hydroplane ate up the mile in 21.98 seconds (163.785 mph). For an official speed run, rules required the boat to make a second try within 15 minutes, going in the opposite direction. The Slo-mo-shun IV refueled in seven or eight minutes. Sayres then pointed the hydroplane south and zipped over the course at 157.2 mph. The combined times were averaged to establish a speed of 160.3235 mph.

It was 7:10 a.m. and the Slo-mo-shun IV had set a world record.

EASY RIDER

Upon reaching the dock at the Sand Point Naval Air Station officers' beach, Sayres told reporters that the ride was "Just like sitting in a comfortable chair in your living room" (Seattle P-I, June 27, 1950). The ride was easy, but the roar of the 1,500-horse-power engine kept Sayres's ears ringing into the evening.

Sir Malcolm Campbell in the Bluebird II had set the previous world speed record on water in August 1939 at 141.74 mph on Lake Coniston in England. By the summer of 1950, his son

Donald Campbell had just installed a more powerful engine in the Bluebird II and was about to try to beat his father's record. Upon learning of Slo-mo-shun IV's record,

Donald Campbell conceded,

"If this is official, then our job is defeated for the time being ... . This speed is out of the range of our present boat and is five miles an hour faster than the speed at which the Bluebird is known to stay on the water"

(The Seattle Times, June 27, 1950)

Stan Sayres also shattered by 33 miles per hour the United States record established by Dan Arena and Jack Shafer on the Such Crust I in Michigan in August 1949.

After winning the world record, Sayres stated, "The boat was not extended" (The Seattle Times, June 10, 1973). He proved it in 1952 when the Slo-mo-shun IV set a new speed record traveling at 178.497 miles per hour. But

Donald Campbell was not to be

denied a rematch. In 1956, on a new jet-driven

boat, he set a new world record traveling on water at a speed of 202.32 mph.

Bow

shot of the famous hydroplane that caused such a stir, retired and on

display for all to marvel at. Even more so when you see the pictures on

this page as to the manner of construction.

KING COUNTRY BUILT and MAINTAINED

The Slo-mo-shun IV was King County's own. The owner, designer, builder, mechanics, and crew were Seattle and King County residents. The only parts of the hydroplane not constructed in Seattle were a surplus World War II airplane engine and the boat's propeller. In addition to Stan Sayres, the following men were on the team that constructed and maintained the Slo-mo-shun IV:

* Ted Jones, designer and one of the drivers, was assistant foremen at Boeing Airplane Company. He lived in McMicken Heights (4612 S 170th) just outside Seattle city limits.

* Anchor Jensen (d. 2000), builder, managed and owned the Jensen Motor Boat Company at 1417 NE Northlake Way where the Slo-mo-shun IV was built. He lived in Seattle's Montlake neighborhood (2715 10th Avenue E).

* Don Spencer built the gearbox. He was an employee of the Western Gear Works in Seattle (417 9th Avenue S).

* Elmer Linenschmidt, mechanic, was a salesman who lived at 7035 Beach Drive near the Fauntleroy neighborhood of Seattle.

* Mike Welch, mechanic, was a cableman for Pacific Telephone and Telegraph, and lived in West Seattle (4702 Beach Drive).

* Jerry Barker, mechanic, an engineer at the Boeing Airplane Company, lived in the View Ridge neighborhood of Seattle (8046 Fairway Drive).

* Doug Miner, a mechanic who owned Miner's Aircraft & Engine Service, lived in Arbor Heights in West Seattle (10635 Marine View Drive).

* Bob Swanson, mechanic, a boat builder at Jensen Motor Boat Company, lived in Shoreline (1222 NE 184th).

* Joe Schobert, a mechanic employed as a dispatcher at Interstate Freight Lines, lived at 5657 42nd Avenue SW in West Seattle.

* Hi Johnson produced the boat's propeller outside of King County in Newport Beach, California.

THE

FIRST RACING HYDROPLANES

Compared

to the K3 and K4 boats of Sir Malcolm Campbell, Slo Mo Shun is a very

nice development that shifts weight distribution to a near ideal, while also

taking care of some of the transmission complexities, and in so doing

improving performance, by way of increasing power to weight ratio. The

main difference was the shift from a two stage flat bottomed hydroplane to

a three pointer, which cured the tendency of the Blue Bird's of Malcolm

Campbell to wander off course at high speed.

Donald Campbell's Bluebird K4 at speed on

Lake Coniston - autographed photograph inscribed: To PC Windle in 1949.

Both the K3 and K4 had drives going forward to a transfer box, that then

had a prop-shaft going aft. The objective of such transmission was to

get the propeller shaft as horizontal as possible to give thrust in the opposite

direction to the travel of the boat

,

as near as possible to 180 degrees, which also tends to counter the

upthrust at the rear that tends to try and rotate the boat. Fortunately,

the forces involved are not so great as to unsettle a very heavy vessel.

When Slo-Mo-Shun IV, set a new world record of 160.32 miles per hour. It added almost 20 miles per hour to the record 141.74 miles per hour Sir Malcolm Campbell made in his Blue Bird II

(K4) in England in 1939. Blue Bird was a costly creation, designed and built solely to capture the world speed record. Slo-Mo-Shun, on the other hand, is suitable for closed-course racing as well as for speed dashes. Stanley S. Sayres of Seattle, its owner, uses it almost like a family runabout. All of the new contenders for the world championship are being designed along the same general lines of Slo-Mo-Shun’s hull.

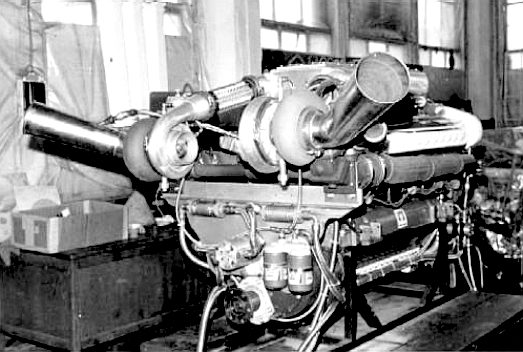

LAKE

WASHINGTON - The Boeing Aqua-Jet is seen here on Lake Washington, a jet engine powered experimental speed boat made by

the famous aircraft company, Seattle, Washington, early 1960s. It is 38 feet long with a 17 foot beam, can reach speeds of 100 knots (115 mph), and is powered by an Allison J-3 turbojet with 4600 pounds of thrust.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Thunderboats

Slo Mo Shun IV article by Fred Farley and David Greene

http://www.thunderboats.org/history/history0188.html

Wikipedia

Allison_Engine_Company

Wikipedia

Water_speed_record

Thunderboats

slomoshun leads the pack

History

Link Stan Sayers SloMoShun

Slomoshun

hydroplanes

Wikipedia

Stanley_Sayres

Wikipedia

Ted_Jones hydroplanes

Jensen

Motor Boats slo mo shun v

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allison_Engine_Company

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Water_speed_record

Bardahl

Asia Pacific

Vintage

Hydroplanes models Jim_Osborne RD_fleet

http://www.bluebirdproject.com

Ballard

News Tribune green-dragon-roars-again

Miss

Bardahl hull_restoration

http://www.missbardahl.com/restoration/hull_restoration/hull_restoration.htm

Miss

Bbardahl

http://www.missbardahl.com/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Bird_K4

Orgsites

Montgomery Model Boat Club

Rolls-Royce-Phantom-electric-blue-Sir-Malcolm-Campbells-water-speed-record

http://www.orgsites.com/al/montgomerymodelboatclub/_pgg9.php3

http://www.bardahl-ap.com/

"Seafair," Typescript, n.d. Seattle Public Library (Call No.

394.26979/Seafair/1961)

Chapter VII, p. 2-3; The Seattle Times, June 26, 1950, p. 1, 23; Ibid.,

June 27, 1950, p. 29; Ibid., September 17, 1956, p. 2; Ibid.,

September 18, 1956, p. 28; Ibid., June 10, 1973,

Ibid.

Magazine section p. 4-5; Seattle Post-Intelligencer June 27, 1950, p. 1, 9-B;

Ibid., September 18, 1956, p. 1.

http://thunderboats.ning.com/profiles/blogs/slomoshun-leads-the-pack

http://www.jensenmotorboat.net/project/slo-mo-shun-v/

http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=1465

http://slomoshunhydros.com/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Sayres

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ted_Jones_%28hydroplanes%29