|

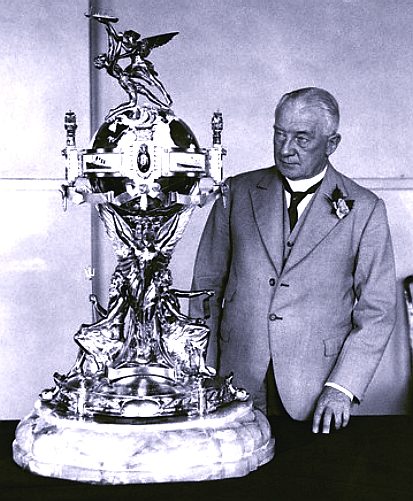

Harold

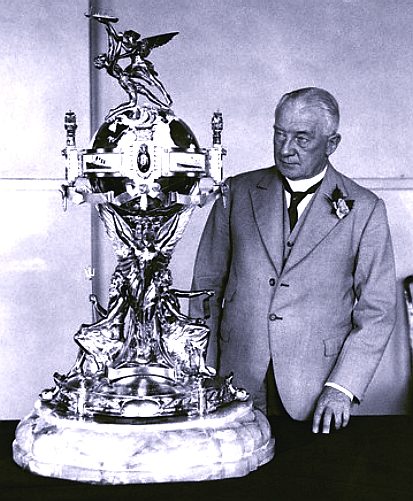

Hales MP in 1935 with his Blue Ribband Trophy

1935

- THE

TROPHY

The trophy was instituted in 1935 when Harold K. Hales (1868 - 1942), a member of the British Parliament and owner of a shipping company, commissioned a Sheffield

golds/silversmith named Charles Holiday to produce a large trophy to be presented to the fastest ship crossing the

Atlantic. For a man so devoted to the sea, it is ironic that it should claim his life.

Mr, Hales died in a boating accident on the River Thames in 1942.

The trophy is a gilt statue, four feet high, weighing nearly 100 lbs., fashioned with a globe resting on two figures of victory (inspired by the big statue of the

Greek goddess Nike that was erected on the island of Samothrace following a victorious sea battle in 305 BC). It stands on a basis of carved green onyx, with an

enameled blue ribbon encircling the middle, and decorated with models of galleons, modern ocean liners and statues of Neptune and Amphitrite, god and

goddess of the sea. It is surmounted by a figure depicting speed pushing a three-stacked (funneled) ocean liner against a figure symbolizing the forces of the

Atlantic.

Prior to 1935 and Harold Hales, there was no

formal trophy to

celebrate the speed increases.

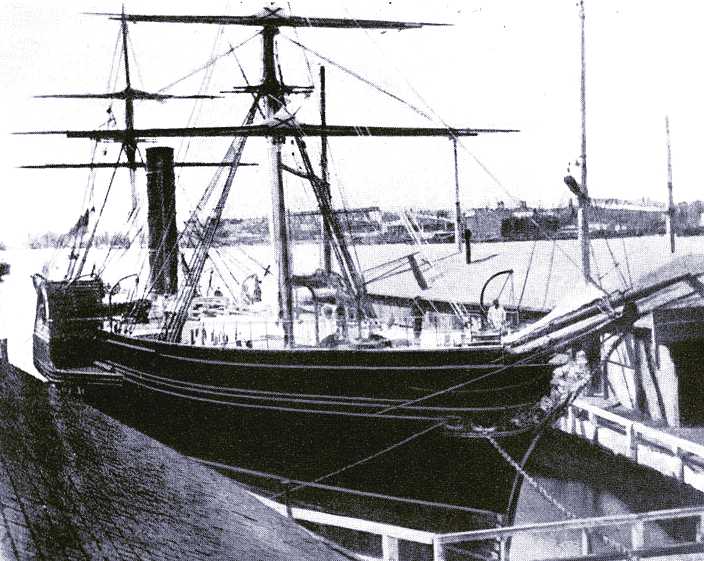

Left:

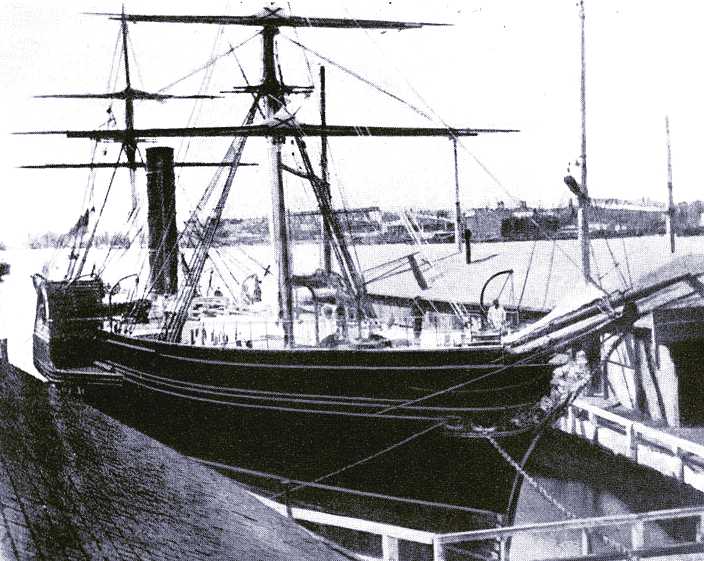

SS Sirius from 1837, crossed the Atlantic in 1837 at 8 knots. She is

thought to be the first ship to hold the title. Right:

RMS Europa, Blue Riband record 11.79 knots

- one of the first photographs of a paddle steamer, which is actually a

paddle assisted sailing ship.

COMPETITION

The

modern cruise passenger, who sees the ship as a major destination in

itself, seldom thinks of speed as an interesting criteria for rating

ships. However,

this was not always so. For over a century and a half there was a

prize - called the Blue Riband - for speed in the North Atlantic crossing.

After

steam conquered that dangerous ocean, the fastest steamer was awarded a

mythical "blue ribbon." The

start may have been Liverpool or Queenstown, but the end was always New

York's Sandy Hook, or later, Ambrose Lightship, a distance of 2,800

nautical miles.

The term was borrowed from

horse racing and was not widely used until after 1910. Under the unwritten rules, the record is based on average speed rather than passage time because ships follow different routes. Traditionally, a ship is considered a "record breaker" if it wins the eastbound speed record, but is not credited with the

Blue Riband unless it wins the more difficult westbound record against the Gulf Stream.

Charles

Holiday the silversmith who crafted this magnificent trophy for Harold

Hales

Of the 35

Atlantic liners to hold the Blue Riband, 25 were British, followed by five German, three American, as well as one each from Italy and France. 13 were Cunarders (plus Queen Mary of Cunard White Star), 5 by White Star, with 4 owned by Norddeutscher Lloyd, 2 by Collins, 2 by Inman and 2 by Guion, and one each by British American, Great Western, Hamburg-America, the Italian Line, Compagnie Générale Transatlantique and finally the United States Lines. Many of these ships were built with substantial government subsidies and were designed with military considerations in mind.

Winston Churchill estimated that the two

Cunard Queens helped shorten the Second World War by a year. The last Atlantic liner to hold the Blue Riband, the

'United States' was designed for her potential use as a troopship as well as her service as a commercial passenger liner.

Competition

was fierce and the rewards were considerable. Although imaginary in

itself, the Blue Riband offered immense tangible rewards. Many passengers

wished to travel on the fastest ship. Contracts for mail carriage and

special freight were considerable. National pride also entered the

picture. During

the 19th century, the size and speed of Atlantic liners grew steadily.

Wooden hulls gave way to iron and steel, propellers replaced paddlewheels,

and auxiliary sails disappeared.

Crossing

time diminished. In 1838 the little Sirius steamed across at 8 knots in 18

days. However, by 1894, the Lucania speeded across at 22 knots in 6 days.

Both ships and most of the early winners flew the British Union Jack.

Apart from some American Collins liners, who surpassed the competition

briefly in the 1850s, England's Cunard, White

Star, and Guion lines

dominated. At

the turn of the century the Germans triumphed. Ships named Kaiser Wilhem

der Grosse and Deutschland shattered the British monopoly.

International

rivalry for supremacy on the North Atlantic reached its zenith in the

early 1930s. British ships had reigned supreme from the 1850s to 1898,

when Norddeutscher Lloyd's Kaiser

Wilhelm der Grosse became the first German ship to win the Blue Riband

for the fastest Atlantic crossing. She was followed by Hapag's Deutschland

and NDL's Kronprinz

Wilhelm; but Britain returned with the steam turbine powered sister

ships Lusitania

and Mauretania

owned by Cunard, the first taking the record in 1907 and the Mauretania

which held the record for two decades, until 1929. From that year

until 1938, the Blue Riband would change hands eight more times between

five ships from four different countries: Germany's Bremen

and Europa

(1929), Italy's Rex,

made a crossing at 29 knots,

France's Normandie

took the prize at just under 30 knots in 1935, and in 1938 ultimately

Britain's Queen Mary, claimed the prize with a speed of over 30

knots (Cunard White Star line).

On

one more occasion the Blue Riband changed hands. The American ship United

States, of United States Line, won the honor with a phenomenal 34-1/2 knot

pace in 1952. By

then, however, the era of jet air traffic had begun. The speed of Atlantic

crossing by ship was no longer of compelling interest.

The

Blue Riband was retired forever, and the era of modern cruising began, in

which ambiance of the ship itself, exotic ports, exquisite cuisine, and

shipboard activity, rather than speed, became the purpose of the cruise.

That was until the era of robot ships. A new Blue-Ribband trophy is on the

horizon. Different rules, but equally as compelling.

The Hales:

Blue Ribband Trophy

HOW

FAST

Unlike other people now planning new passenger ships, it is an integral

part of this project to produce the fastest passenger ship of all time.

Just as the

Queen Elizabeth 2,in 1969,was regarded by almost all as the

last large passenger ship...now numerous larger ones up to twice the size

are building...so the speed record is generally regarded as forever to be

held by the SS United States, unless one counts small craft never designed

for carrying passengers across oceans. But that is an issues sorely

contested.

Technology has not stood still since the SS US set its formal record in

1952,nor is there any reason that it should be considered the monopoly of

short-haul ferries. It is time the task of engineers was set to rewriting

the record book.

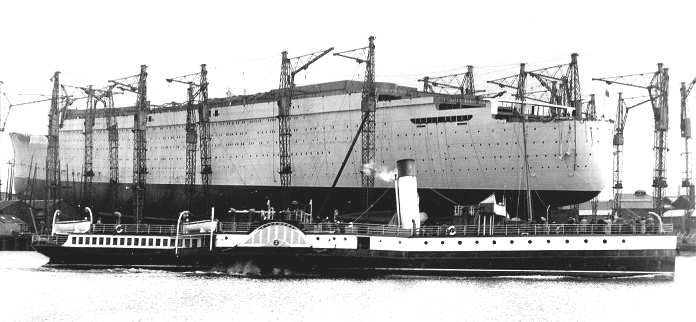

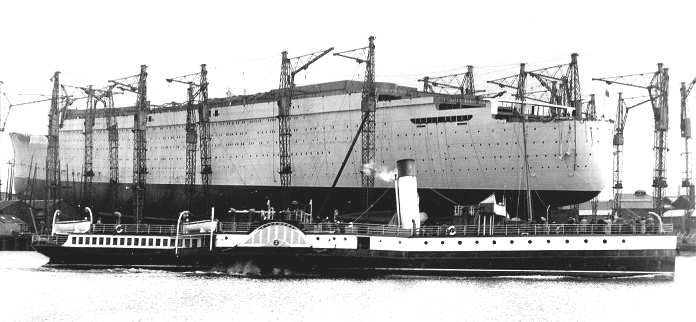

The

Queen Mary, Blue Riband record holder 1936

THE

HULL SPEED BARRIER

A factor known in ship design circles is the hull speed, which depends on

the length of the ship. The longer a ship, the faster it can theoretically

go. Designers refer to this as the speed/length ratio.

Length in feet Hull speed (Knots) Actual speed (Knots)

477.7(Aries) 29.2 45

882.7(Titanic) 39.8 22

963(Queen Elizabeth 2) 41.5 28.5(peak service,32 claimed top)

990(SS US) 42.1 35.59 and higher

1019(Queen Mary) 42.7 31.69

1029(Normandie) 42.9 29.98

1100 44.4 ?

1150 45.4 ?

1200 46.4 ?

1250 47.3 ?

1300 48.3 ?

As you can see it's not quite that simple. A ship with a poor design like

Titanic can fall well short on hull speed. A ship like Aries, a new

Italian mono-hull fast ferry, can exceed its hull speed through planing,

like a speedboat, which is also how the Destriero at 222 feet with a hull

speed of 19.9 knots, managed to grab the Atlantic absolute speed record

with a crossing at 53.09 knots. Hull speed is supposed to be for a

"displacement mono-hull", hence a catamaran like Catalonia (whose

299' length would give it a hull speed of 23.1 knots, but which crossed

the Atlantic at 38.77) or its identical sister Cat-Link V (39.9 knots point

to point,41.284 with detour) or a hydrofoil or

hovercraft does not come

under this formula. Further, the formula is fudgy. The length for the

Queen Mary above is its overall length, but hull speed applies strictly to

its waterline length, somewhere between that and its 975' length between

perpendiculars.

With displacement

mono-hulls design is still a major factor. Although

the Normandie was slower with a higher hull speed than the Queen Mary, the

Queen Mary had 25% more power needed to produce its superior speed.

Its

hull was actually a slower, fatter, deeper-displacing design. The SS

United States, with a lower hull speed but more power(240,000 HP) than

either, reportedly *used* less power than either(150,000 vs. 160,000 for

Normandie and 200,000 for Queen Mary) to break their records. On its

trials it officially did 38.23 knots, but unofficially is understood, at

full power, to have reached 43 knots with a theoretical top of 44

(officially it was 41.75). In other words, it exceeded its supposed

hull speed.

Hull speed is not a strictly limiting

factor, but is usually a practical limiting one. Power offers less and less of a return per unit

added when you reach hull speed. Various factors in the shape of the hull

optimize performance, including high length-to-beam ratios, planing

tendencies, and more.

Given the opportunity to apply new technology to the design of the

hull, a new engine technology that makes higher power easier to obtain

than ever before, and the will to build a new vessel of heroic size,

records can be shattered.

SS United States, Blue Riband record holder

1952

WHAT

SPEED IS POSSIBLE

In optimizing a hull design while maintaining compatibility with existing

or obtainable harbors and

facilities and the ocean-liner paradigm, one must stick to the slender

mono-hull, with a high length-to-beam ratio. Catamarans and planing hulls

are a price too high, a sale of the soul of the concept. The ships of

these types that break speed records are not designed for a liner's tasks.

From the table above, one can tell that a ship of the

size

under consideration would have a hull speed of roughly 45 to 47 knots. To

do a better job of performing relative to hull speed than the SS United

States is a reasonable design goal.

41.3 knots is the current minimum goal for a routine service speed, in

order to provide Blue Riband level service as a norm. However, this is

only a starting point. A record barely set is a record prone to being

re-broken.

The speed attainable would of course influence the schedule. A logical

service goal is weekly round trips, with excess speed over the minimum

needed for this enabling additional stops.

The shortest navigable distance between

New York and

Southampton is

about 3169 nautical miles, so allowing for non-ideal routes in practice a

*pier-to-pier* average speed of 40 knots would yield a crossing time of 80

hours and allow 4 hours turnaround...a little bit more than the QE2's

record, but uncomfortably less than its scheduled interval (over 9 hours).

(A Gigantic turnaround would differ from a QE2 turnaround in needing to

handle more passengers, but fewer provisions per passenger). Of course,

the crossing could not all take place at a set high speed...if one assumes

10% must take place at an average of 20 knots,42 knots on the remaining

90% would give an average of 39.8 knots,43 knots on 90% would give an

average of 40.7 knots, 44 knots on 90% would give an average of 41.6 knots, and 45 knots on 90% would give an average of 42.5 knots for the

whole voyage.

44 knots on the high-speed 90% of the crossing and 20 knots on the

rest, then, would enable a crossing time of 3 days 5 hours to be

scheduled, with 7-hour turnarounds, and 45 knots on the high-speed portion

would cut the crossing by over an hour more. This range would be within

hull speed, and within the engineering capability of the ship, though not

very easy to sustain. To go higher would be desirable if it could be made

reliable, but effectiveness at the margin would bear serious scrutiny.

Averaging 42.5 knots en route would cut a New York-Cape Town or Cape

Town-Melbourne crossing to six and a half to seven days, and

Melbourne-Vancouver to seven and a half...recall that the QE2 takes

fourteen weeks or more for a world cruise, and even though we are talking

about a ship that would have to go around Cape Horn, you can see that this

could be cut in half if desired and multiple scenic stops still added.

(Like the QE2,there would likely be one world cruise a year, but

ocean-crossing would be more predominant)

WHAT

ABOUT COMFORT

It's not enough, of course, to just be able to power through the water in

record time. Passengers must also be kept comfortable, not let feel they

are riding on a skipping stone! Stabilizers have been devised to aid

sea-keeping in recent decades, the SS United States pioneered them...but

they exact a penalty in speed, more important to a speed-conscious liner

than to the modern cruise ship. So the technology of the stabilizers for

the new liner will have to be advanced as the hull design...to produce the

highest *stabilized* speed in history when the sea conditions warrant.

When the Lusitania was sinking many of the chains

were not released and thus preventing the boats from being launched

successfully. Many boats went down with the ship.

|

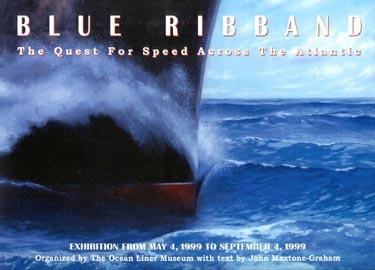

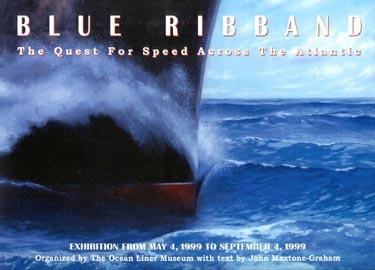

7C's - Blue

Ribband the Sea Quest for Speed Across the Atlantic

|

Yesterday's

greyhounds are lovingly remembered in this parade of evocative steel

thoroughbreds, history's favorites that set the pace. Famous companies include

Inman, Cunard, Collins and White Star's sail and paddle steamers, sail and

propeller steamers and pure steamships, the first German challenge; Cunard and

Britain's response; Bremen, Europa and Rex; Normandie, the first Queen and

finally, Gibb's Triumph. A publication for an exhibition of the same title by

the Ocean Liner Museum. Text by John Maxtone-Graham 74 pages. Numerous

illustrations from private collections. Softback.

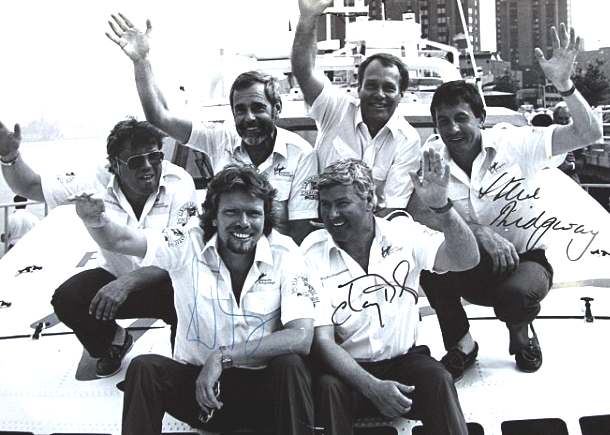

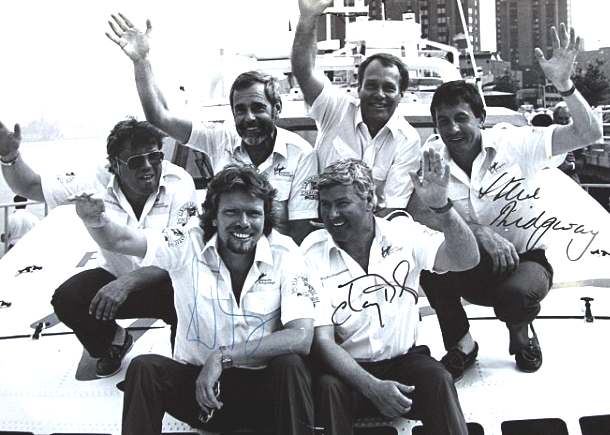

VIRGIN

ATLANTIC CHALLENGER 1986 - JUNE 2013 In 1986,

Richard Branson was successful in setting a new

gas-guzzling eastbound

transatlantic speed record in the powerboat Challenger II. He was not awarded the Hales trophy because his boat was not a commercial

vessel and the direction was the wrong way to qualify as a Blue Riband

record. RETURN

TO PLYMOUTH The Virgin Atlantic Challenger II sailed into British waters for the first time in 16 years – and straight into

Plymouth harbour.

Dan Stevens was beaming with pride as he showed off Sir Richard Branson's former

yacht to a waiting crowd. He' rescued it from the scrapheap.

The vessel arrived near the Mayflower steps shortly before midday on Sunday and was met by scores of people eager to have a look around.

Mr Stevens, who owns Mount Batten Ferries is quoted as saying: "It's epic to bring her back into British waters. It's brilliant. I'm glad that I was in a position to save such an historic boat." Mr Stevens

has big plans to restore the Virgin Atlantic Challenger II to her former glory. He will race her in the

Cowes Torquay at the end of September and the round-Britain race next year.

The boat was discovered in Majorca a few months ago and Dan bought it from an unnamed owner.

He explained: "It was through an agent who was instructed to sell the boat; it just came about through pure chance really.

"We got talking and I was in a position to purchase the boat and I wanted to do that because of what she has achieved and her place in maritime history.

"If I didn't step in, or someone else step in that was willing to do the refit, then it would have gone to scrap. It's been sat aside for seven years."

Sir Richard Branson has already said he is watching Mr Stevens' progress "with interest".

Under the business giant's ownership, the Virgin Atlantic Challenger II took the record for the fastest Atlantic crossing – three days, eight hours and 31 minutes – in 1986.

The 72ft vessel was commissioned by Branson for the historic Blue Riband Transatlantic Challenge.

She is powered by two 2,000HP engines and has a top speed of 52 knots. Mr Stevens continued: "It's only done 800 hours on the clock; a lot of that was done up until 1996. It's only done 70 since then."

Built by Lowestoft Boatyard in the UK using hull and propulsion designs by Sony Levi, the

Aluminium Delta Hull and Superstructure with twin MTU and Levi Surface Drives develop 4000hp giving the 21.95 meter vessel (52,000 kg) a top speed of 52 knots.

The craft is fitted out in original Virgin Airways Cabin Livery and Upholstery. Built to a very high standard with all instrumentation functioning and is equipped with Automatic Flotation System, Automatic

Fire Extinguishing System, Dual Helm Positions with Twin Radar System. Everything is in very good original condition.

The asking price on www.theyachtmarket.com

was £249,000 GBP.

Sir Richard's first attempt to break the TransAtlantic record was in the Challenger I, which capsized, receiving widespread media coverage, in 1985.

The 32-ton vessel overturned just 140 miles short of its target, the Isles of Scilly off

Cornwall. She was on-track to break the record. Heartbreakingly,

Challenger I took just six minutes to sink, and the crew was forced to scramble to safety.

As Richard was rescued he saw a copy of the Daily Mail, which featured a copy of his baby son Sam, now 27:

'As I got on (the rescue boat) I saw a copy of the Daily Mail and it had a picture my newly-born son, who I hadn't actually seen.'

The crew were spotted floating in life boats by helicopters from the Royal Navy air station at

Culdrose, Cornwall. They were picked up by a passing ship and airlifted to hospital.

6

AUGUST 2013 - DAILY MAIL - 27 YEAR REUNION Sir Richard Branson was today reunited with his record-breaking, ocean-going superboat - which broke down on a trip to a fish and chip shop.

The tycoon made history in 1986 when the Virgin Atlantic Challenger II crossed the Atlantic faster than ever.

The 72ft boat - then worth £1.5million - spent years languishing in a marina in Majorca until it was spotted by sailing fanatic Dan Stevens.

Dan, of Plymouth, Devon, spent around £450,000 buying and restoring the

gas-guzzling powerboat to its former glory and sailed it back to Britain. He welcomed Sir Richard, 63, and his original crew back on board yesterday for a 40-mile spin from Plymouth to Fowey in Cornwall.

They were headed for a fish and chip lunch - but en route the legendary powerboat immediately ran into trouble and conked out.

Sir Richard said: 'Some debris got stuck in the engine which delayed us for 20 minutes or so.

'Dan went slightly white, but it was all sorted very quickly. It seems drama seems to follow this boat.'

Sir Richard was joined by his navigator Dag Pike and original crew members Steve Ridgway, Eckie Rastig, Peter McCann and Chris Witty.

Sir Richard said yesterday: 'It's magnificent. I've got enormous respect for the team that secured it and put it back together.

'She rides beautifully, we nearly got her up to full speed, 50 knots. It was just lovely to see it back again. I never thought we'd see it in the water again.

'It's very strange meeting people that you haven't seen for 30 years but it was a delight. We had two great adventures together and when you're in a boat that's sinking very quickly, when you go through experiences like that together it's great to get back together.

'Everybody is extremely well, but quite a bit older.'

Was the adventure-loving entrepreneur tempted to buy Virgin Atlantic Challenger II back?

'I talked to Dan and he wants to save it for the UK. He's talking to one or two museums on the coast that specialise in ships and we'd love to help him keep it in the UK.

'Over 1,000 people turned up today, there is enormous interest in it.'

Merchant navy officer Dan, 39, was looking round a boatyard last year when he recognised the fading red paintwork and Virgin logos and decided to take a closer look.

Incredibly he found the interior piled high with charts and maps - almost exactly as Branson left it after smashing the world record.

The Challenger II was commissioned by Sir Richard for the historic Blue Riband Transatlantic Challenge.

His first attempt a year earlier in 1985 had ended in disaster - with the Challenger I sinking off the coast of Cornwall.

But in 1986 in his Virgin Atlantic Challenger II, with sailing expert Daniel McCarthy, he beat the record by two hours.

Despite the crossing he was denied the official 'Blue Riband' trophy by the trustees of the award because they said he made the trip in a 'toy boat' rather than an ocean liner.

It is believed the 98 kph craft was sold by Virgin Media in the late 1980s to a sultan who barely used it.

It then spent about years moored in the Spanish port accumulating storage fees until Mr Stevens repaired the two 2,000HP engines so it could sail back to the UK.

Dan, a ferry company boss from Plymouth, has refused to reveal how much he paid for Challenger II but its value was listed on various boating websites as £250,000.

The boat, which has a top speed of 52 knots, has only chalked up little more than 810 hours of seafaring despite its fame.

He said: 'She has a nice feeling about her and she's more than capable of 45 knots.

'Everyone thought I was daft when I bought it, but I'm crazy about boats. I just did not want it to go to scrap.

'It's been an amazing and memorable day. It was great to have Richard on board and have a chat with him.

'I'm not sure what my plans are for the boat. I can't afford to keep it myself so I may sell it on. It's part of British maritime history so it needs to be preserved.'

Mike Sutherland, who was harbourmaster at Fowey in 1982 when the Challenger II last came into the harbour, said: 'It was great to be here to see it come in. I remember it very well.

'There were hundreds of people gathered at the harbour when the crew came in. It's fantastic to see similar scenes here now.'

HOVERSPEED

1990 In 1990, the 242-foot (74 m) catamaran passenger/car ferry

Hoverspeed Great Britain was scheduled to take a delivery voyage from her Australian builders to begin cross channel operations. Her owners confirmed with the Hales trophy trustees in the UK that their vessel would be eligible for the trophy if they beat the United States record, even though the ship would not actually carry passengers on the trip. The trustees ruled that the ship still met the criteria. After Hoverspeed Great Britain's successful voyage, the Maritime Museum considered challenging the decision on the grounds that Hales donated the award for ships providing Atlantic passenger service, but decided not to because of the cost of legal fees. There

is also the small matter that the ship went the wrong way; eastbound! Builder: Incat Tasmania Pty Ltd.

Length overall: 73.60m

Length waterline: 59.90m

Beam: 26.00m

Beam of Hulls: 4.33m

Draft: 3.10m

Speed: 37 knots

Max Deadweight – 185 to 230 tonnes

Fuel Capacity – 4 x 8900 litres integral aluminium tank and additional long range tank in each hull.

Main Engines – 4 x resiliently mounted Ruston 16RK270 marine diesel engines at 4050 kW each.

Water Jets – 4 x Lips LJ115DX. Two waterjets configured for steering and reverse. Transmission – direct drive.

Ride Control combines active trim tabs aft and optional T-foil with active fins located at the forward end of each Welded

Aluminium hull. The trophy case at the academy remained empty for the next eight years until Carnival Cruise Lines loaned the museum a replica of the trophy. In 1992, the Italian powerboat Destriero made a voyage at 53.09 knots (98.32 km/h), breaking Challenger II's record. The current holder of the Hales Trophy is the catamaran Cat-Link V (now Fjord Cat) for a 1998 delivery voyage (without passengers) at 41.3 knots (76.5 km/h). However, the United States is still considered the holder of the Blue Riband.

Incat chairman Robert Clifford in 1998 with the Hales Trophy, a heavily gilded ornate trophy over 1m in height – the trophy is currently displayed at Incat in Hobart.

Incat Ltd asked the New York Maritime Museum for the trophy who considered challenging the request on the grounds that Hales donated the award for ships providing Atlantic passenger service but decided not to because of the cost of legal fees. The trophy case at the New York Maritime Museum remained empty for the next eight years, until Carnival Cruise Lines loaned the museum one of two replica Hales Trophies they had commissioned; costing $40,000 dollars each.

The Hales Trophy for the fastest transatlantic crossing by a passenger ship is not only a test of speed, but a test of endurance and reliability. The essence of the Hales Trophy is to, “encourage the continued development of technology and design in passenger shipping. The Blue Riband is a pennant (A blue flag), to be proudly flown aloft by the title holder.

It is the prize awarded to the ship which makes the fastest crossing of the North Atlantic. To gain this prestigious honour a liner had to beat both previous Eastward and Westward records, on the same voyage. The two points on either side of the Atlantic between which the race is run are Bishop Rock off the Scilly Isles and the Ambrose light off New York harbour.

DESTRIERO

1992 - UNOFFICIAL RECORD 53 KNOTS Destriero is a 67-metre (220 ft) long, 13-metre (43 ft) wide, 400-ton displacement, 60,000-horsepower (45,000 kW) yacht built by Fincantieri in 1991. She is rumoured to belong to the Aga Khan.

The yacht was originally fitted with three GE Aviation LM1600 gas turbines, providing her with a maximum speed of 110 kilometres per hour (68 mph; 59 kn).

She raced for the Blue Riband award in 1992, but was denied it, because Destriero was classed as a "private yacht" and not a "commercial passenger vessel", despite sailing at an as yet unbeaten speed record of 53.1 knots average from New York to England without refueling.

The ship was "laid up" in HMNB Devonport dockyard, Plymouth, England for ten years, but was removed in February 2009,reportedly for Lürssen ship yard.

20th

ANNIVERSARY JULY 1992 - 2012

Earlier this week, a celebration took place at the Muggiano shipyard in La Spezia, to celebrate of the twentieth anniversary of Destriero, the fastest yacht in the world which crossed the Atlantic in 1992, setting a record which still remains unbeaten.

The monohull, built in 1991 in less than a year by Fincantieri, sailed 3,106 nautical miles without refueling, from Ambrose Light, New York to Bishop Rock lightship on the Scilly Isles, England, in 58 hours at an average speed of 53 knots (reaching peaks of 70), and won once more the Blue Riband which in 1933 had been awarded to the legendary transatlantic liner, the Rex.

In order to celebrate the challenge, on September 5th 1992 the Destriero was assigned also the Virgin Atlantic Trophy by the English tycoon Richard Branson for the fastest crossing with no regulation limits and the Columbus Atlantic Trophy by the New York Yacht Club for the double crossing.

Built at the shipyards of Muggiano and Riva Trigoso, Destriero was at that time the largest ship in light alloy ever to be constructed. At 67 metres with a beam of 13 metres and 60,000 hp of available power, the yacht could reach average speeds of over 60 knots. Destriero marked the beginning of the production of a new generation of high speed vessels with consequent benefits for commercial and occupational development at Fincantieri .

The challenge of the Destriero started with the aim to break the record for crossing the Atlantic. Her adventure was born out of the passion for naval technology of Ismaili Prince Karim Aga Khan, at that time President of the Costa Smeralda Yacht Club. He sponsored the initiative, supported by leading testimonials of Italian industry and culture of the time.

After the event Cesare Fiorio, head of the Destriero Challenge program and pilot during the crossing, said "The Destriero is so important because she left a mark universally recognized by fans and not; she is a milestone in the shipping history and thanks to her we got on to high-speed navigation".

Corrado Antonini, Chairman of Fincantieri, commented "Fincantieri is building in its US shipyards a brand-new line of Litoral Combat Ships, the US Navy backbone of the future. Thanks also to the Destriero experience we succeeded in entering the most challenging and prestigious market: the US Defence one".

Fincantieri Yachts

+39 0187 543 238

fincantieriyachts@fincantieri.it

MARCH

2011 - His Highness Aga Khan sets sail on Alamshar. Though a wealthy leader with millions of followers he is also known to be a generous contributor and good hearted person in the Islamic world of today. He has commissioned a

$200 million mega yacht called ‘Alamshar’ which is named after the champion racehorse owned by the great Aga Khan himself. Though work began 12 years ago at Devonport in UK, there has not been much progress since and the yacht has only managed 30 knots on its maiden voyage. The 165 ft super yacht has been seen for the first time undergoing sea trials for what is understood to be an attempt to capture the Blue Riband.

TELEGRAPH

NOVEMBER 2007 -

AGA KHAN'S £100 MILLION BOAT

One of the world's richest men is preparing a fresh assault on the trans-Atlantic speed record using a British-built boat.

Constructed in secret at a former naval dockyard in Devon and the subject of speculation on specialist websites, the 165ft super-yacht has been seen for the first time undergoing sea trials for what is understood to be an attempt to capture the Blue

Riband.

Known only as Project 305, the £100 million yacht will soon be named

Alamshar, after the champion racehorse owned by the Aga Khan, the Islamic religious leader and prince who is heir to a vast family fortune.

The builders of Alamshar, DML of Plymouth, hoped to power the vessel using three

Rolls-Royce gas turbine engines originally designed for Sea King

helicopters, which would push her to a record speed of 80 knots (92.2mph).

But technical problems, including a fire during a test off Cornwall - the turbine blades burnt out because of the demands made on them - means they are being replaced with engines to drive water jets rather than rotors by Rolls-Royce's American rival Pratt and Whitney.

Despite the veil of secrecy around the project, the yacht's cover was blown by a local sailor Neil Hope, who spotted it off

Kingsand, near Plymouth, last month.

He said: "I started taking photographs and a launch headed over. They asked me to stop snapping, but as the vessel was in a public place I don't see that they had the right to do so."

At full power, the yacht hopes to smash the world speed record for super yachts, set at 65 knots by the New Zealand-built

'The World is Not Enough' in 2004.

Alamshar is an evolution of another previous Aga Khan vessel, Shergar. It boasts a specialised hull made of

high tensile yet lightweight aluminium. The yacht is expected to tip the scales at around 400 tons - a fraction of what is normal for a yacht of its class.

One workman, who was involved at the start of the project, said: "You wouldn't believe how often the spec has been changed or something has been refitted because the original was going to add too much weight."

The Hayes Trophy, which accompanies the Blue Riband title, is only awarded to vessels certified to carry passengers, meaning that the Aga Khan may only be able to capture the speed award.

This scuppered his previous attempt to claim the title with Destriero in 1992 when he broke the Atlantic crossing record in a time of two days, 10 hours and 34 minutes at an average speed of 53.09 knots. The award can be won either eastbound or westbound.

Sir Richard Branson's Virgin Atlantic Challenger also failed in 1986 because it was not a passenger ship. It also stopped to take on fuel.

The holder of the Blue Riband is a former Channel ferry, Cat-Link V, a catamaran that made the eastbound Atlantic crossing in two days, 20 hours and nine minutes in 1998 at an average speed of 41.2 knots.

A sea trial source said: "Alamshar is the most incredible thing of her type and she will capture the public imagination when the wraps finally come off."

INCAT

TRIPLE SUCCESS JUNE 2010

In June of 2010 (then 20 years ago) shipbuilder Incat Tasmania claimed the world record for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic Ocean.

The Hobart based shipbuilding company says that 23 June 2010 marks 20 continuous years that Incat built fast ships have held the record for the fastest Transatlantic crossing.

On 23 June 1990 Hoverspeed Great Britain, a ship built by Incat for operation between England and France by Sea Containers Ltd, broke the record for the fastest crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by a commercial passenger ship.

The crossing from Ambrose Light at New York commenced at 7.30pm on June 19, 1990 and the 2922 mile trip ended at Bishop Rock in the UK on the morning of 23 June.

The Hales Trophy is awarded to "The ship which shall for the time being, have crossed the Atlantic Ocean at the highest average speed" Incat says that it is not simply reaching the highest speed momentarily, the right to fly the Blue Riband is a test of endurance as well, because the high speed needs to be maintained over the entire crossing (naturally slower at the beginning with a full fuel load and becoming faster at the end of the journey).

The previous record had been held for 38 years by the SS United States (1952 - 1990), prior to the SS United States win, the great liners vied for the honour to fly the Blue Riband.

Hoverspeed Great Britain held the record, and the owners held the trophy, until another Incat built ship Catalonia took the record in June 1998, then just a month later in July 1998 a further ship built by Incat, CatLink V broke the record.

Incats says this was the first time in the history of the transatlantic records (dating back to the 1860s) that three ships to win the trophy in succession had been built by the same shipyard.

Maricuda

Blue Ribband contender 2013

APRIL

2011 - MARICUDA PROJECT >

The Maricuda project to win the Hales Trophy, the Blue Riband of the Atlantic has gained significant momentum recently with its association and assistance from General Electric, Renk, Wartsila and Devonport Yachts. The design process of the Maricuda Atlantic Challenger, the craft that is being designed to cross the Atlantic in under two days is closer to becoming a reality.

The remarkable 80 metre (220 ft) Maricuda Project ‘superyacht’ that is being developed will enable ocean-going craft to travel thousands of miles

without

re-fuelling, at almost twice the current acknowledged speeds. The structure and mechanical components are currently undergoing rigorous stress analysis to prove that this new marine engineering technology will work on the day.

The Maricuda team, led by Managing Director David Aitken MSc, recently visited the Devonport Yachts, Pendennis Shipbuilding yard in Falmouth with a

BBC cameraman to record the excellent progress this project is making. The Hales Trophy Trustees supplied Maricuda with a detailed image of the Hales Trophy for the occasion and this can be seen both in the new ‘Investors Brochure’ and on the website at www.maricuda.co.uk.

Consider the merits of halving the duration of ocean travel. Air-freight could return to the seas and consequently revive harbours and ports around the world. Passenger ferry operators could travel further or travel the current distance in half the time. International borders can be better protected. Drug enforcement agencies could excel.

Offshore energy sites could be swiftly serviced. The military and rescue services could perform with even more remarkable efficiency.

Maricuda has set its sights on introducing this radical new technology as soon as investors and / or sponsors are ‘on board’. To prove the engineering and showcase the new technology, the Maricuda Atlantic Challenger will secure the Hales Trophy. This challenge, the Blue Riband, is the ultimate speed event for man and machine, 3500 miles across the Atlantic Ocean in the fastest time ever.

Inspired

by the Hales Trophy and the Blue Ribband competitions, the Bluebird World

Cup Trophy was commissioned for the Cannonball International series

of road runs in 2014.

In addition, every entrant

completing one of the recognized prestigious international series of

courses, will qualify for a Blue

Riband (a blue ribbon made of silk) a mark of distinction and meritorious

endeavor, which they might proudly display with any competing vehicle,

team, corporate or other event, etc.

Sponsors or vehicle producers

could have qualified for

this accolade in gold, silver and bronze categories. BMS has

commissioned an artist to design the ribbon and medallion. The above

depiction is for illustrative purposes, where the proposed events did

not proceed.

BLUE

RIBAND RECORD HOLDERS (Westbound)

| Ship |

Year |

Dates |

Line |

From |

To |

Distance |

Time |

Speed |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Columbia

USA

|

1830

|

1

– 17 April

|

Black

Ball Line

|

Portsmouth

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,222

nautical miles (5,967 km)

|

15

d, 23 h

|

8.41

knots (15.58 km/h)

|

|

Great

Western UK

|

1838

|

8

– 23 April

|

GW

|

Avonmouth

|

New

York

|

3,220

nautical miles (5,960 km)

|

15

d, 12 h, 0 m

|

8.66

knots (16.04 km/h)

|

|

Great

Western UK

|

1838

|

2

– 17 June

|

GW

|

Avonmouth

|

New

York

|

3,140

nautical miles (5,820 km)

|

14

d, 16 h, 0 m

|

8.92

knots (16.52 km/h)

|

|

Great

Western UK

|

1839

|

18

May–31 May

|

GW

|

Avonmouth

|

New

York

|

3,086

nautical miles (5,715 km)

|

13

d, 12 h, 0 m

|

9.52

knots (17.63 km/h)

|

|

Columbia

UK

|

1841

|

4

– 15 June

|

Cunard

|

Liverpool

|

Halifax

|

2,534

nautical miles (4,693 km)

|

10

d, 19 h, 0 m

|

9.78

knots (18.11 km/h)

|

|

Great

Western UK

|

1843

|

29

April–11 May

|

GW

|

Liverpool

|

New

York

|

3,068

nautical miles (5,682 km)

|

12

d, 18 h, 0 m

|

10.03

knots (18.58 km/h)

|

|

Cambria

UK

|

1845

|

19

– 29 July

|

Cunard |

Liverpool

|

Halifax

|

2,534

nautical miles (4,693 km)

|

9

d, 20 h, 30 m

|

10.71

knots (19.83 km/h)

|

|

America

UK

|

1848

|

3

– 12 June

|

Cunard |

Liverpool

|

Halifax

|

2,534

nautical miles (4,693 km)

|

9

d, 0 h, 16 m

|

11.71

knots (21.69 km/h)

|

|

Europa

UK

|

1848

|

14

– 23 October

|

Cunard |

Liverpool

|

Halifax

|

2,534

nautical miles (4,693 km)

|

8

d, 23 h, 0 m

|

11.79

knots (21.84 km/h)

|

|

Asia

UK

|

1850

|

18

May–27 May

|

Cunard |

Liverpool

|

Halifax

|

2,534

nautical miles (4,693 km)

|

8

d, 14 h, 50 m

|

12.25

knots (22.69 km/h)

|

|

Pacific

USA

|

1850

|

11

– 21 September

|

Collins

|

Liverpool

|

New

York

|

3,050

nautical miles (5,650 km)

|

10

d, 4 h, 45 m

|

12.46

knots (23.08 km/h)

|

|

Baltic

USA

|

1851

|

6

– 16 August

|

Collins

|

Liverpool

|

New

York

|

3,039

nautical miles (5,628 km)

|

9

d, 19 h, 26 m

|

12.91

knots (23.91 km/h)

|

|

Baltic

USA

|

1854

|

28

June – 7 July

|

Collins

|

Liverpool

|

New

York

|

3,037

nautical miles (5,625 km)

|

9

d, 16 h, 52 m

|

13.04

knots (24.15 km/h)

|

|

Persia

UK

|

1856

|

19

– 29 April

|

Cunard

|

Liverpool

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,045

nautical miles (5,639 km)

|

9

d, 16 h, 16 m

|

13.11

knots (24.28 km/h)

|

|

Scotia

UK

|

1863

|

19

– 27 July

|

Cunard

|

Queenstown

|

New

York

|

2,820

nautical miles (5,220 km)

|

8

d, 3 h, 0 m

|

14.46

knots (26.78 km/h)

|

|

Adriatic

UK

|

1872

|

17

May–25 May

|

W.Star

|

Queenstown

|

Sandy

Hook

|

2,778

nautical miles (5,145 km)

|

7

d, 23 h, 17 m

|

14.53

knots (26.91 km/h)

|

|

Germanic

UK

|

1875

|

30

July – 7 August

|

W.Star

|

Queenstown

|

Sandy

Hook

|

2,800

nautical miles (5,200 km)

|

7

d, 23 h, 7 m

|

14.65

knots (27.13 km/h)

|

|

City

of Berlin UK

|

1875

|

17

– 25 September

|

Inman

|

Queenstown

|

Sandy

Bank

|

2,829

nautical miles (5,239 km)

|

7

d, 18 h, 2 m

|

15.21

knots (28.17 km/h)

|

|

Britannic

UK

|

1876

|

27

October – 4 November

|

W.Star

|

Queenstown

|

Sandy

Hook

|

2,795

nautical miles (5,176 km)

|

7

d, 13 h, 11 m

|

15.43

knots (28.58 km/h)

|

|

Germanic

UK

|

1877

|

6

– 13 April

|

W.Star

|

Queenstown

|

Sandy

Hook

|

2,830

nautical miles (5,240 km)

|

7

d, 11 h, 37 m

|

15.76

knots (29.19 km/h)

|

|

Alaska

UK

|

1882

|

9

– 16 April

|

Guion

|

Queenstown

|

Sandy

Hook

|

2,802

nautical miles (5,189 km)

|

7

d, 6 h, 20 m

|

16.07

knots (29.76 km/h)

|

|

Alaska

UK

|

1882

|

14

May–21 May

|

Guion

|

Queenstown

|

Sandy

Hook

|

2,871

nautical miles (5,317 km)

|

7

d, 4 h, 12 m

|

16.67

knots (30.87 km/h)

|

|

Alaska

UK

|

1882

|

18

– 25 June

|

Guion

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,886

nautical miles (5,345 km)

|

7

d, 1 h, 58 m

|

16.98

knots (31.45 km/h)

|

|

Alaska

UK

|

1883

|

29

April–6 May

|

Guion

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,844

nautical miles (5,267 km)

|

6

d, 23 h, 48 m

|

17.05

knots (31.58 km/h)

|

|

Oregon

UK

|

1884

|

13

– 19 April

|

Guion

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,861

nautical miles (5,299 km)

|

6

d, 10 h, 10 m

|

18.56

knots (34.37 km/h)

|

|

Etruria

UK

|

1885

|

16

– 22 August

|

Cunard

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,801

nautical miles (5,187 km)

|

6

d, 5 h, 31 m

|

18.73

knots (34.69 km/h)

|

|

Umbria

UK

|

1887

|

29

May – 4 June

|

Cunard

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,848

nautical miles (5,274 km)

|

6

d, 4 h, 12 m

|

19.22

knots (35.60 km/h)

|

|

Etruria

UK

|

1888

|

27

May – 2 June

|

Cunard

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,854

nautical miles (5,286 km)

|

6

d, 1 h, 55 m

|

19.56

knots (36.23 km/h)

|

|

City

of Paris UK

|

1889

|

2

May–8 May

|

Inman

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,855

nautical miles (5,287 km)

|

5

d, 23 h, 7 m

|

19.95

knots (36.95 km/h)

|

|

City

of Paris UK

|

1889

|

22

– 28 August

|

Inman

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,788

nautical miles (5,163 km)

|

5

d, 19 h, 18 m

|

20.01

knots (37.06 km/h)

|

|

Majestic

UK

|

1891

|

30

July – 5 August

|

W.Star

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,777

nautical miles (5,143 km)

|

5

d, 18 h, 8 m

|

20.10

knots (37.23 km/h)

|

|

Teutonic

UK

|

1891

|

13

– 19 August

|

W.Star

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,778

nautical miles (5,145 km)

|

5

d, 16 h, 31 m

|

20.35

knots (37.69 km/h)

|

|

City

of Paris UK

|

1892

|

20

– 27 July

|

Inman

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,785

nautical miles (5,158 km)

|

5

d, 15 h, 58 m

|

20.48

knots (37.93 km/h)

|

|

City

of Paris UK

|

1892

|

13

– 18 October

|

Inman

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,782

nautical miles (5,152 km)

|

5

d, 14 h, 24 m

|

20.70

knots (38.34 km/h)

|

|

Campania

UK

|

1893

|

18

– 23 June

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,864

nautical miles (5,304 km)

|

5

d, 15 h, 37 m

|

21.12

knots (39.11 km/h)

|

|

Campania

UK

|

1894

|

12

– 17 August

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,776

nautical miles (5,141 km)

|

5

d, 9 h, 29 m

|

21.44

knots (39.71 km/h)

|

|

Lucania

UK

|

1894

|

26

– 31 August

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,787

nautical miles (5,162 km)

|

5

d, 8 h, 38 m

|

21.65

knots (40.10 km/h)

|

|

Lucania

UK

|

1894

|

23

– 28 September

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,782

nautical miles (5,152 km)

|

5

d, 7 h, 48 m

|

21.75

knots (40.28 km/h)

|

|

Lucania

UK

|

1894

|

21

– 26 October

|

Cunard

|

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,779

nautical miles (5,147 km)

|

5

d, 7 h, 23 m

|

21.81

knots (40.39 km/h)

|

|

Kaiser

Wilhelm der Grosse GM

|

1898

|

30

March – 3 April

|

NDL

|

The

Needles

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,120

nautical miles (5,780 km)

|

5

d, 20 h, 0 m

|

22.29

knots (41.28 km/h)

|

|

Deutschland

GM

|

1900

|

6

– 12 July

|

Hapag

|

Eddystone

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,044

nautical miles (5,637 km)

|

5

d, 15 h, 46 m

|

22.42

knots (41.52 km/h)

|

|

Deutschland

GM

|

1900

|

26

August – 1 September

|

Hapag

|

Cherbourg

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,050

nautical miles (5,650 km)

|

5

d, 12 h, 29 m

|

23.02

knots (42.63 km/h)

|

|

Deutschland

GM

|

1901

|

26

July – 1 August

|

Hapag

|

Cherbourg

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,141

nautical miles (5,817 km)

|

5

d, 16 h, 12 m

|

23.06

knots (42.71 km/h)

|

|

Kronprinz

Wilhelm GM

|

1902

|

10

– 16 September

|

NDL

|

Cherbourg

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,047

nautical miles (5,643 km)

|

5

d, 11 h, 57 m

|

23.09

knots (42.76 km/h)

|

|

Deutschland

GM

|

1903

|

2

– 8 September

|

Hapag

|

Cherbourg

|

Sandy

Hook

|

3,054

nautical miles (5,656 km)

|

5

d, 11 h, 54 m

|

23.15

knots (42.87 km/h)

|

|

Lusitania

- UK

|

1907

|

6

– 10 October

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,780

nautical miles (5,150 km)

|

4

d, 19 h, 52 m

|

23.99

knots (44.43 km/h)

|

|

Lusitania

- UK

|

1908

|

17

May–21 May

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,889

nautical miles (5,350 km)

|

4

d, 20 h, 22 m

|

24.83

knots (45.99 km/h)

|

|

Lusitania

- UK

|

1908

|

5

– 10 July

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Sandy

Hook

|

2,891

nautical miles (5,354 km)

|

4

d, 19 h, 36 m

|

25.01

knots (46.32 km/h)

|

|

Lusitania

- UK

|

1909

|

8

– 12 August

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Ambrose

Light

|

2,890

nautical miles (5,350 km)

|

4

d, 16 h, 40 m

|

25.65

knots (47.50 km/h)

|

|

Mauretania

- UK

|

1909

|

26

– 30 September

|

Cunard |

Queenstown |

Ambrose

Light

|

2,784

nautical miles (5,156 km)

|

4

d, 10 h, 51 m

|

26.06

knots (48.26 km/h)

|

|

Bremen

GM

|

1929

|

17

– 22 July

|

NDL

|

Cherbourg

|

Ambrose

Light

|

3,164

nautical miles (5,860 km)

|

4

d, 17 h, 42 m

|

27.83

knots (51.54 km/h)

|

|

Europa

GM

|

1930

|

20

– 25 March

|

NDL

|

Cherbourg

|

Ambrose

Light

|

3,157

nautical miles (5,847 km)

|

4

d, 17 h, 6 m

|

27.91

knots (51.69 km/h)

|

|

Bremen

GM

|

1933

|

27

June – 2 July

|

NDL

|

Cherbourg

|

Ambrose

Light

|

3,149

nautical miles (5,832 km)

|

4

d, 16 h, 48 m

|

27.92

knots (51.71 km/h)

|

|

Rex

IT

|

1933

|

11

– 16 August

|

Italian

|

Gibraltar

|

Ambrose

Light

|

3,181

nautical miles (5,891 km)

|

4

d, 13 h, 58 m

|

28.92

knots (53.56 km/h)

|

|

Normandie

FR

|

1935

|

30

May – 3 June

|

CGT

|

Bishop

Rock

|

Ambrose

Light

|

2,971

nautical miles (5,502 km)

|

4

d, 3 h, 2 m

|

29.98

knots (55.52 km/h)

|

|

Queen

Mary UK

|

1936

|

20

– 24 August

|

C-WS

|

Bishop

Rock

|

Ambrose

Light

|

2,907

nautical miles (5,384 km)

|

4

d, 0 h, 27 m

|

30.14

knots (55.82 km/h)

|

|

Normandie

FR

|

1937

|

29

July – 2 August

|

CGT

|

Bishop

Rock

|

Ambrose

Light

|

2,906

nautical miles (5,382 km)

|

3

d, 23 h, 2 m

|

30.58

knots (56.63 km/h)

|

|

Queen

Mary UK

|

1938

|

4

– 8 August

|

C-WS

|

Bishop

Rock

|

Ambrose

Light

|

2,907

nautical miles (5,384 km)

|

3

d, 21 h, 48 m

|

30.99

knots (57.39 km/h)

|

|

United

States USA

|

1952

|

11

– 15 July

|

USL

|

Bishop

Rock

|

Ambrose

Light

|

2,906

nautical miles (5,382 km)

|

3

d, 12 h, 12 m

|

34.51

knots (63.91 km/h)

|

THE

BLUE RIBAND BALL - FRIDAY 13 DECEMBER 2013 On Friday 13th December

Harrow School

Enterprises invited the public to join them as they set sail for an evening of fine food and entertainment. The Shepherd Churchill Hall

was being transformed for the evening into an Ocean Liner of the 1920s in aid of the SPEAR charity. “A night of entertainment and glamour of the 20s Ocean Liners in aid of charity”

Join us on Friday 13th December as we set sail for an evening of fine food and entertainment. The Shepherd Churchill Hall

was being transformed for the evening into an Ocean Liner of the 1920s in aid of the SPEAR charity.

We can only imagine the fun it must have been to attend such an event.

HEV

ATLANTIC GLIDER 2013 > This

is a live project which claims to be

to design and develop the World’s most innovative, efficient high speed passenger and payload carrying vessel. The

Challenge is to cross from the position of the former Ambrose Light, New York to the United Kingdom’s Bishops Rock Lighthouse in a time of less than 58 hours (record

by Destriero in 1992) using only one fuel load. The vessel is being designed not just for speed and efficiency but

with the aim to lead the way in commercial naval architecture and provide the benchmark for the future of high speed, high efficiency commercial vessel design.

The ethos is that with modern innovation and ‘F1 style’ application of design processes,

that ships can be built to significantly reduce CO2 emissions into the atmosphere.

The

'Atlantic Glider' has got to be one of the most unusual designs put

forward as a contender for the Blue Riband. Having said that, two thin

hulls that pierce the waves, stands as much chance as any mono-hull. In

this case it is the superstructure that lets the concept down. Air drag

should always be a consideration in any high speed vessel.

PROJECT KAILANI

This is the code name for their vessel development project. The team comprises high speed powerboat racers, architects, designers, aerospace engineers, business and marketing experts who are currently focused on achieving

their stated objectives.

The project is being undertaken low key with cross border partners. They

wish to retain a level of secrecy until they are able to unveil the vessel

being designed. That shown above is an early concept model. These

are the stated objectives:

* ATLANTIC GLIDER will be a high speed catamaran

* Her hull is being developed from tried and tested vessel technology

* She will be propelled by a newly designed propulsion technique

* She should be extremely attractive and made from advanced composites

* She will traverse the 3106 miles of Atlantic Ocean using only 1 fuel load and in the best comfort possible

* She will carry the latest marine industry navigation and crew/passenger safety systems

* She could become a Global Ambassador for latest in passenger and payload THE TEAM The Atlantic GLIDER challenge

has produced a team of world class professionals who include ultra high speed powerboat racing drivers, marketing and event management, ocean challenges and adventure, naval architecture and engineering.

They have experience in computerised analysis (FEA and CFD and 3D and Reverse Engineering) and practical vessel construction techniques in the latest composite materials.

CONTACTS FOR ATLANTIC GLIDER

Glider Marine Limited

Hideaway, Pool Mill Membland,

Newton Ferrers Devon, PL8 1HS

Tel: +44 (0)7500 977687

Two

different makes of gin that use similar branding, but no doubt each has

their own distinctive taste and geographical area of trade. But why call

an alcoholic drink 'Blue Riband.' Unless it is the official drink served

aboard a ship that holds the Atlantic record.

Mc

DOWELL'S BLUE RIBAND GIN Blue Riband Gin is one of the oldest Gins in

the Indian marketplace, and still it tastes good. The brand is not that dissimilar

to many other Indian Gins, it is described as faintly sweet. It is traded by a reputed group and

widely distribute. Blue Riband is claimed to be one of the best selling

gin brands worldwide.

McDowell’s Blue Riband Premium Extra Dry Gin comprises an Alcohol By Volume(ABV) of 42.5%, which is 3.2% more than

is common for other traditional London Dry Gins. You can anticipate paying approximately $30 for a bottle of McDowell’s Blue Riband Premium Extra Dry Gin, which is 3.4% more costly than the average

for other gin alcoholic beverages.

A

chocolate bar called Blue Riband. Why? The candy is brown, the cream

filing is brown. The name is hardly likely to tease our appetites. So why?

NESTLE

BLUE RIBAND CARAMEL CREAM BISCUITS Nestle's

crisp wafer coated in milk chocolate snack, Blue Riband, was launched in 1936 and is a real family

favourite. It contains 99 Calories per bar with no artificial colours, flavours or preservatives. Nestle Blue Riband Caramel Cream

(8x19.3g = 155grams)

Eight crisp caramel flavour wafer biscuits covered in milk chocolate

Ingredients

Milk Chocolate (45%) (Sugar, Dried Whole Milk, Cocoa Butter, Cocoa Mass, Lactose and Proteins from Whey, Whey Powder, Vegetable Fat, Emulsifier (Sunflower Lecithin), Butterfat) , Wheatflour , Sugar , Vegetable Fat , Flavourings , Fat-Reduced Cocoa Powder , Salt , Raising Agent (Sodium Bicarbonate) , Colour (Paprika Extract) , Emulsifier (Soya Lecithin)

If

you are going to call a beer 'Blue Ribbon', then at least have the decency

to tie a ribbon around the neck of the bottle, or stick a bit of blue silk

somewhere - like the label.

BLUE

RIBBON BEER - PABST Pabst Blue Ribbon (PBR) is an American brand of beer sold by Pabst Brewing Company, originally established in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1844, but now based in Los Angeles. Pabst Blue Ribbon is contract-brewed in six different breweries around the U.S. in facilities owned by Miller Brewing Company (a few of which were actually Pabst breweries at one time).

Originally called Best Select, and then Pabst Select, the current name came from the blue ribbons that were tied around the bottle neck, a practice that ran from 1882 until 1916.

TASTE

Charlie Papazian, president of the Brewers Association, published the following tasting notes for Pabst Blue Ribbon in 2008:

"A contrasting counterpoint of sharp texture and flowing sweetness is evident at the first sip of this historic brew. A slowly increasing hoppiness adds to the interplay of ingredients, while the texture smooths out by mid-bottle. The clear, pale-gold body is light and fizzy. Medium-bodied Blue Ribbon finishes with a dusting of malts and hops. A satisfying American classic and a Gold Medal winner at the 2006 Great American Beer Festival."

PEAK SALES

Sales of Pabst peaked in 1977, when they reached 18 million barrels. In 1980 and 1981, the company had four different CEOs, and by 1982 it was fifth in beer sales in the U.S., dropping from third in 1980.

In 1996, Pabst headquarters left Milwaukee, and the company ended beer production at

the company's main complex in downtown Milwaukee.

By 2001, the brand's sales were below a million barrels. That year, the company got a new CEO, Brian Kovalchuk, formerly the CFO of Benetton, and major changes at the company's marketing department were made.

In 2010, food industry executive C. Dean Metropoulos bought the company for a reported $250 million.

In June 2011, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission forced two advertising executives to cease efforts to raise $300 million to buy the Pabst Brewing Company. The two had raised over $200 million by

crowd-sourcing, collecting pledges via their website, Facebook, and Twitter.

MARKETING REVIVAL

The beer experienced a sales revival in the early 2000s after a two decade-long slump, largely due to its increasing popularity among urban hipsters. Although the Pabst website features user-submitted photography, much of which features twenty-something Pabst drinkers dressed in alternative fashions, the company has opted not to fully embrace the

counter-cultural label in its marketing, fearing that doing so could jeopardize the very "authenticity" that made the brand popular (as was the case with the poorly received OK Soda). Pabst instead targets its desired market niche through the sponsorship of indie music, local businesses, facial hair clubs (RVA Beard League), post-collegiate sports teams, dive bars and radio programming like National Public Radio's All Things Considered. The beer has also been featured prominently in films such as Blue Velvet, Everything Must Go and Gran Torino, and in television shows such as AMC's Breaking Bad and South Park. The company encourages fan art to be submitted online, and is subsequently shown on the beer's official Facebook page.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

The

Telegraph

Aga Khan's £100m boat after Blue Riband title Blue

Riband boats Lux

Issues his-highness aga khan sets sail on alamshar The

Blue Riband Club Wikipedia

Destriero Superyacht

Times Aga Kahn's Alamshar http://www.blueriband-boats.com/ http://www.atlanticglider.com/introducing-atlantic-glider/ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1568954/Aga-Khans-100m-boat-after-Blue-Riband-title.html Atlantic

Glider Fincantieri

Yachtst http://www.fincantieri.it http://www.theblueriband.com/ http://www.charterworld.com/80-metre-220-ft-maricuda-project-win-hales-trophy-blue-riband-atlantic http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Riband Richard-Branson-reunited-record-breaking-superboat-27-years-fastest-vessel-cross-Atlantic The

Blue Riband Oxford

Dictionaries blue-riband Nestle-Blue-Riband-Caramel-Cream Nestle

UK chocolate_and_confectionery Blue Riband Wikipedia

Pabst_Blue_Ribbon http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/blue-riband http://www.britishshopabroad.com/products/Nestle-Blue-Riband-Caramel-Cream-%288x19.3g%29.html http://www.nestle.co.uk/brands/chocolate_and_confectionery/biscuit/blueriband http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pabst_Blue_Ribbon http://www.theyachtmarket.com/boats_for_sale/106416/ http://www.motorship.com/news101/industry-news/incat-celebrates-20-years-of-records http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blue_Riband http://www.luxissues.com/his-highness-aga-khan-sets-sail-on-alamshar/ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Destriero http://www.superyachttimes.com/editorial/35/article/id/8991 http://uptospeednews.co.uk/tag/hales-trophy/

|