|

The

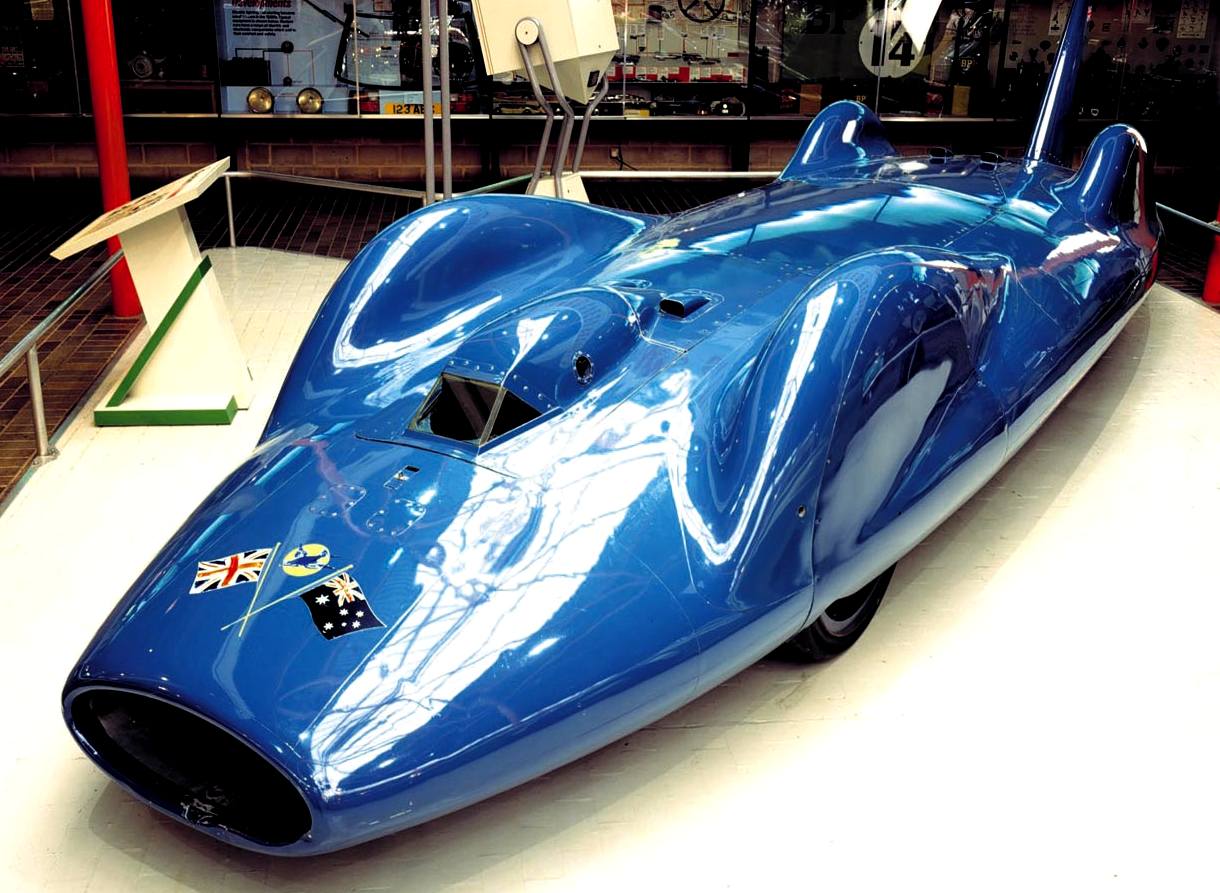

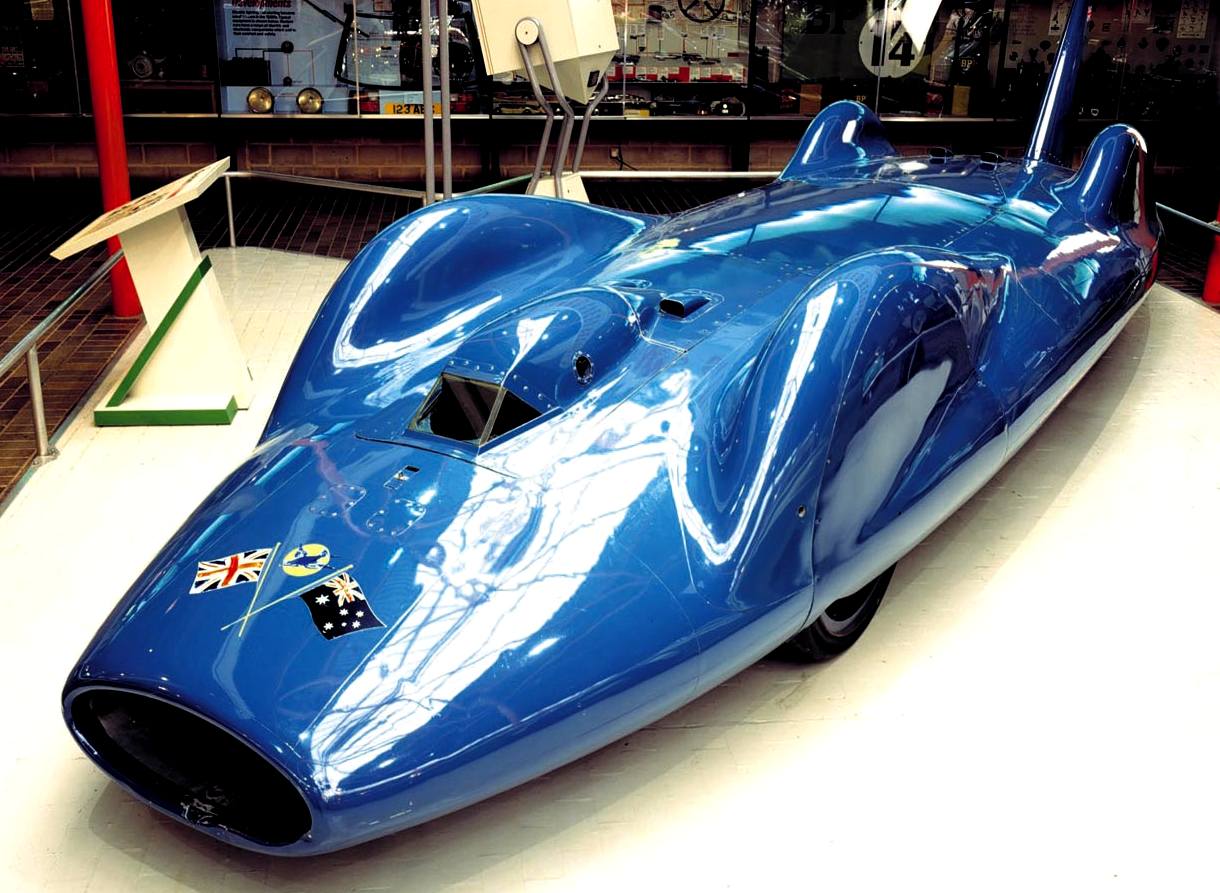

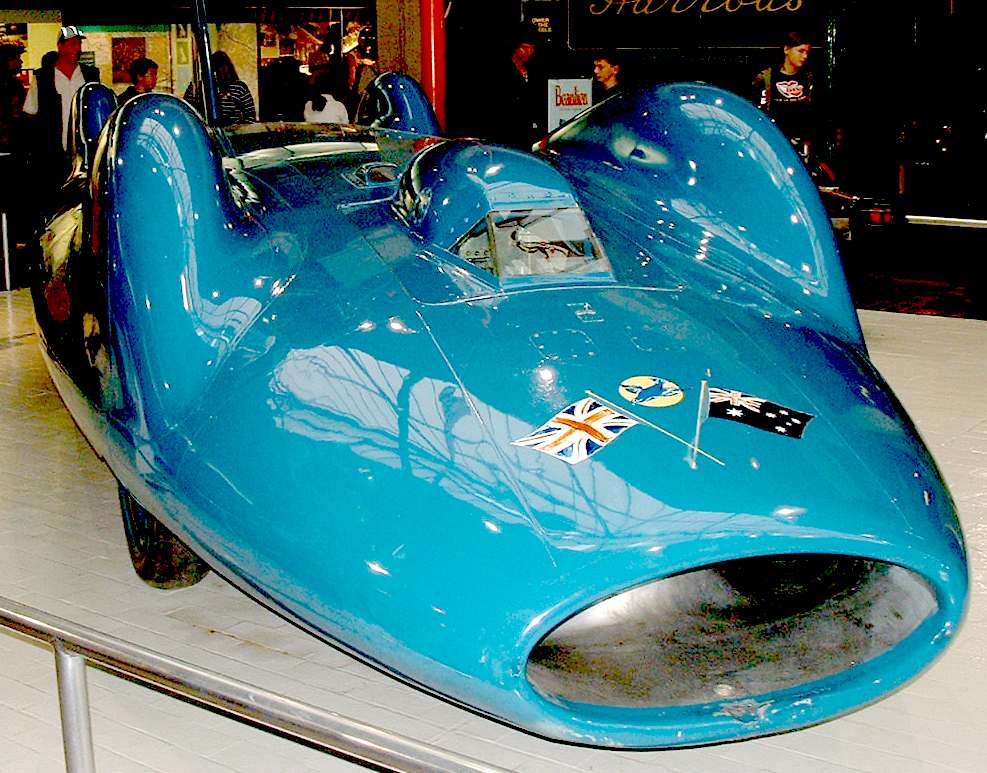

BlueBird CN7 (Campbell Norris) at the National Motor Museum at

Beaulieu

Donald

Campbell started messing about in boats after he bought the K4

from the auction of his father's estate. It was the K4 that stirred

Donald's imagination, who in turn sparked Ken and Louis Norris to think

of putting a gas-turbine engine in a car. It was the logical next step

in getting things to go faster.

The Bluebird-Proteus CN7 was a technologically advanced wheel-driven land speed record-breaking car, driven by Donald Campbell, built in 1960 and rebuilt in 1962.

The design concept

was certainly simple. Take a jet engine - run drive shafts out of each end

to the front and rear axles and build a steel frame to house the engine driver

and wheels. Well, that's how it started. But hundreds of drawings

later and £1,000,000 spent, the vehicle sported a bonded aluminium honeycomb chassis,

with huge wheels all covered in a voluptuous ally body.

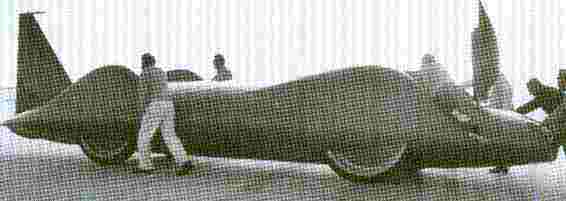

5 miles to go chaps - pushing the jet

Bluebird to base. Getting things in proportion - CN7's wheels

In fact, the shape

(aerodynamics) of the cn7 was very similar to John Cobb's Mobil Railton Special

which almost achieved 400 mph using petrol engines and no tail fin - dare we say

John Cobb's car inspired Donald Campbell and Ken and Louis Norris, the designers

of the cn7 = campbell/norris 7. Bluebird started out without a tail fin. Ken

confirmed this in conversation.

Not long

after topping John Cobbs 390mph + record, the Summers brothers raised the record

above that of the cn7 using 4 petrol engines, comparatively smaller wheels and

budget, in Goldenrod.

But no-one can deny the spectacle of the cn7, perhaps only eclipsed by Richard

Noble's Thrust SSC charging across the desert sands.

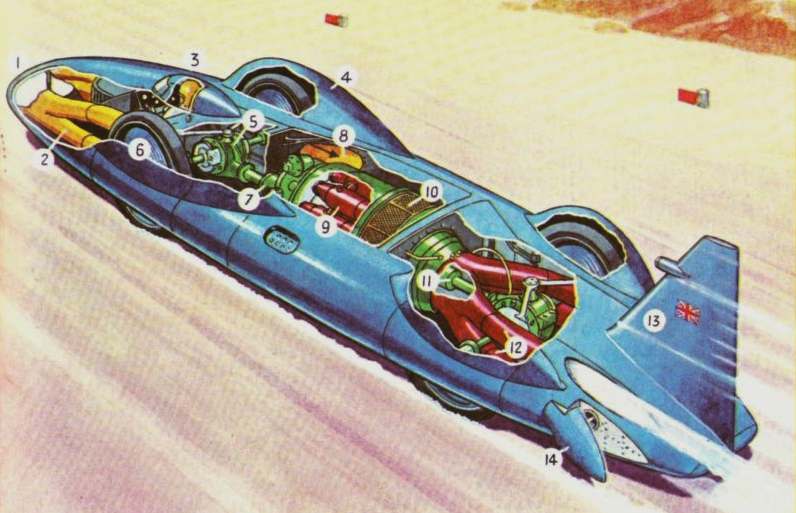

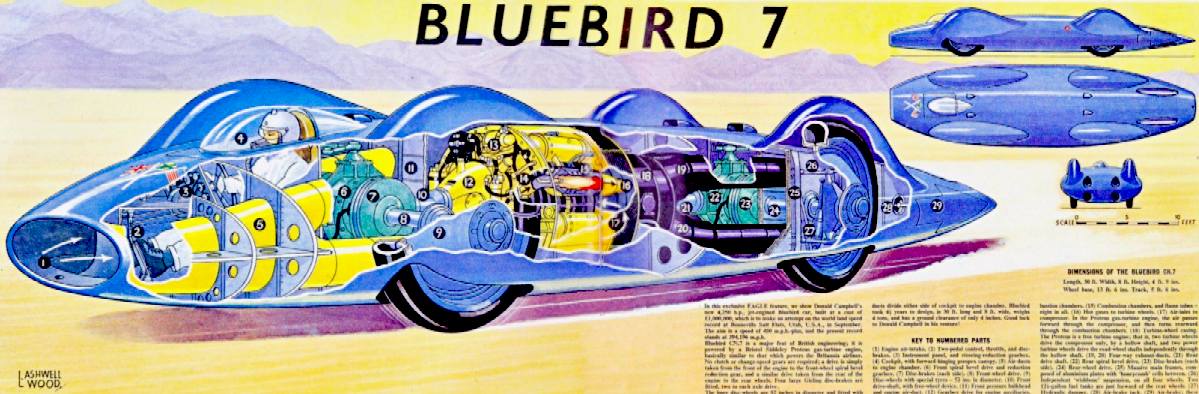

CN7 DESIGN

In 1956, Campbell began planning a car to break the land speed record, which then stood at 394 mph (630 km/h). The Norris brothers, who had designed Campbell's highly successful Bluebird K7 hydroplane designed Bluebird-Proteus CN7 with 500 mph (800 km/h) in mind. The car weighed in at 4 tons and was built with an advanced

aluminum honeycomb sandwich of immense strength, with fully independent suspension. The car had 4 wheel drive, through 52 inch Dunlop wheels / tyres, air brakes as well as all round inboard disc brakes. The CN7 (Campbell–Norris 7) was built by Motor Panels in Coventry, and was completed by the spring of 1960, and was powered by a Bristol-Siddeley Proteus free-turbine (turboshaft) engine of 4,450 shp (3,320 kW).

Motor

Panels of Coventry and Dunlop were big sponsors of the CN7

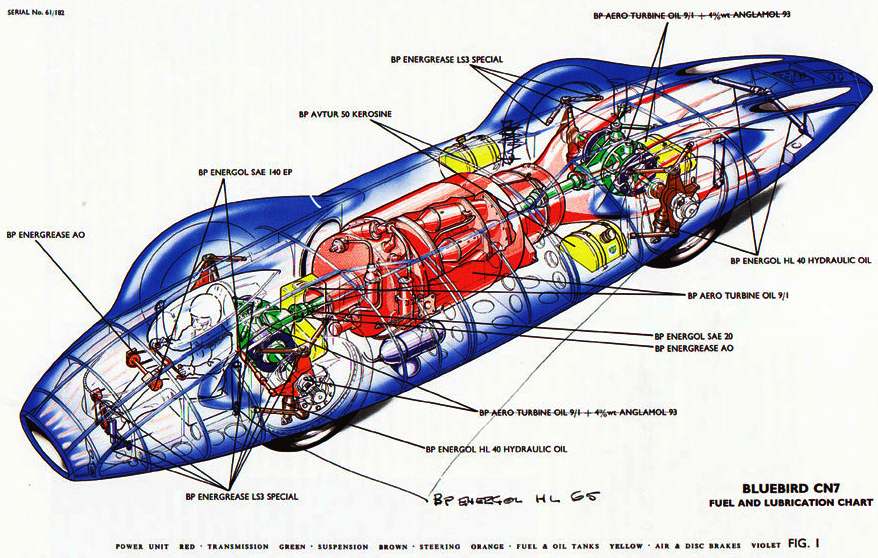

CN7 ENGINE

The Bristol-Siddeley Proteus was the Bristol Aeroplane Company's first successful gas-turbine engine design, a turboprop that delivered over 4,000 hp (3,000 kW). The Proteus was a two spool, reverse flow

gas

turbine. Because the turbine stages of the inner spool drove no compressor stages, but only the propeller, this engine is sometimes classified as a free turbine. The engine, a Proteus 705, was specially modified to have a drive shaft at each end of the engine, to separate fixed ratio gearboxes on each axle.

GOODWOOD 1960

Campbell demonstrated his Bluebird CN7 Land Speed Record car at Goodwood Circuit in July 1960, at its initial public launch and again in July 1962. The laps of Goodwood were effectively at 'tick-over' speed, because the car had only 4 degrees of steering lock, with a maximum of 100 mph on the straight on one lap.

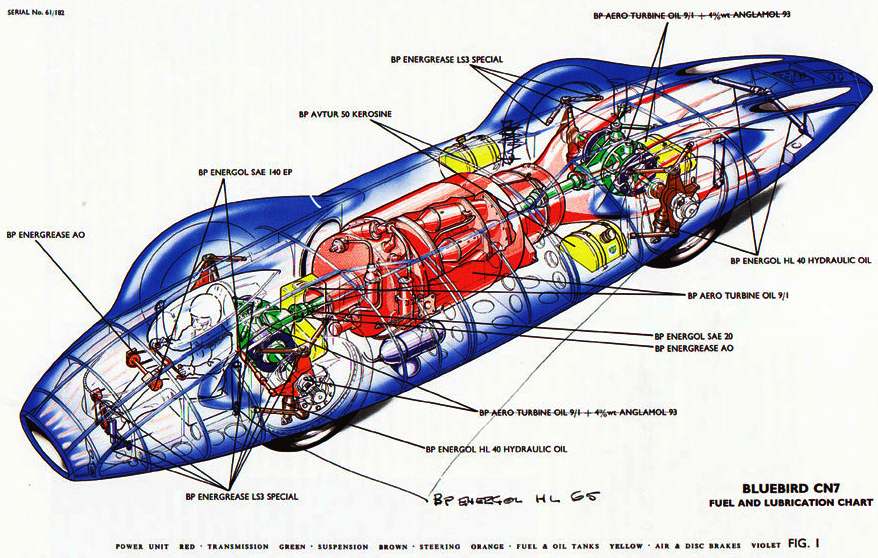

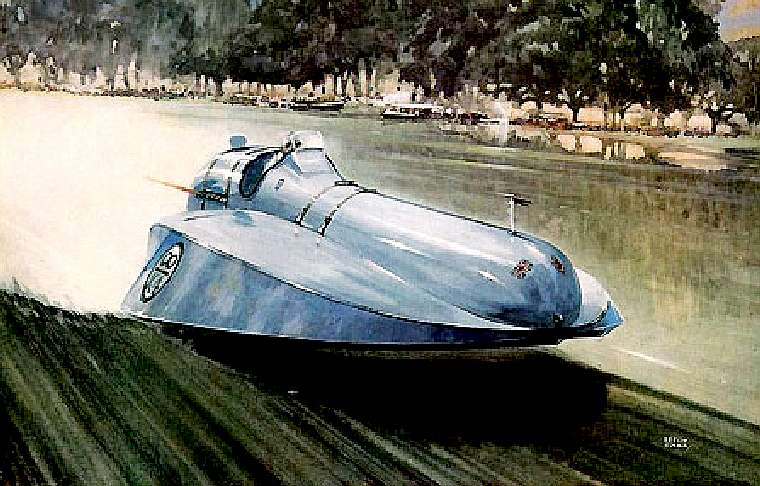

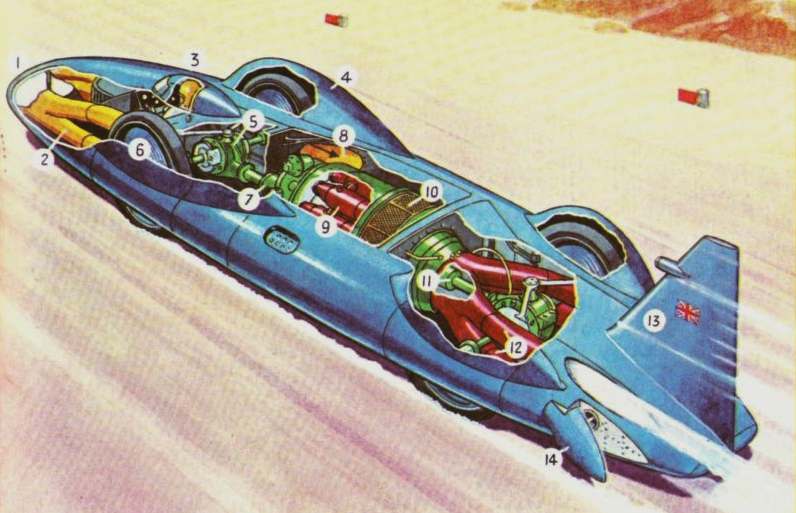

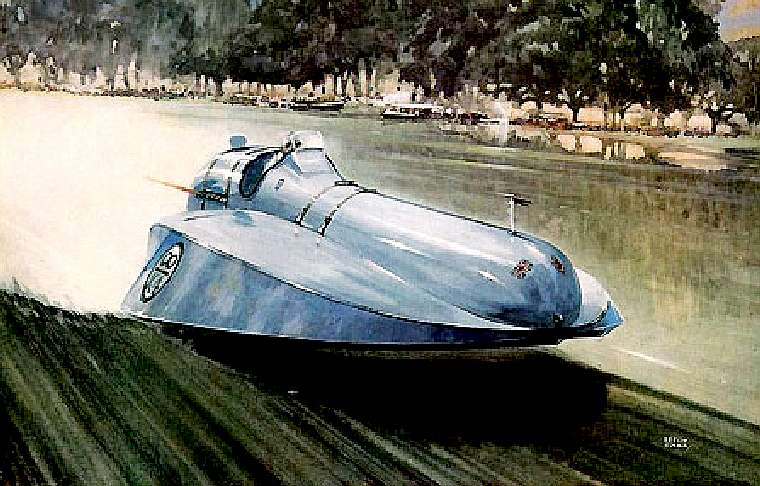

LEFT:

A painting by John Pittaway - Bluebird CN7 DC How Long a Mile Lake Eyre.

RIGHT: A cutaway drawing of the CN7 as used in motoring and educational

articles.

BONNEVILLE 1960

Following the low-speed tests conducted at Goodwood, the CN7 was taken to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah, USA, scene of his father's last LSR triumph in 1935. The attempt, which was heavily sponsored by BP, Dunlop as well as many other British motor component companies, was unsuccessful and CN7 was written off following a high-speed crash on the 16th of September. Campbell suffered a fracture to his lower skull, a broken ear drum as well as cuts and bruises. He convalesced in California until November 1960. Meanwhile plans had been put in motion to rebuild CN7 for a further attempt.

His confidence was severely shaken, he was suffering mild panic attacks, and for some time he doubted whether he would ever return to record breaking. As part of his recuperation he learned to fly light aircraft and this boost to his confidence was an important factor in his recovery. By 1961 he was on the road to recovery and planning the rebuild of CN7.

The

Bluebird team arrive in Australia, destination Lake Eyre

LAKE EYRE 1963

The rebuilt car was completed, with modifications including differential locks and a large vertical stabilising fin, in 1962. After initial trials at Goodwood and further modifications to the very strong

fibreglass cockpit canopy, CN7 was shipped this time to Australia for a new attempt at Lake Eyre in 1963. The Lake Eyre location was chosen as it offered 450 square miles (1,170 km2) of dried salt lake, where rain had not fallen in the previous 20 years, and the surface of the 20 miles (32 km) long track was as hard as concrete. As Campbell arrived in late March, with a view to a May attempt, the first light rain fell. Campbell and Bluebird were running by early May but once again more rain fell, and low-speed test runs could not progress into the higher speed ranges. By late May, the rain became torrential, and the lake was flooded. Campbell had to move the CN7 off the lake in the middle of the night to save the car from being submerged by the rising flood waters. The 1963 attempt was over. Campbell received very bad press following the failure to set a new record, but the weather conditions had made an attempt out of the question.

BP pulled out as a sponsor at the end of the year.

Any good map of Australia shows a number of blue patches named Lake this or Lake that, the largest being

Lake Eyre, lying nearly 500 miles north of Adelaide. However, none of these are lakes in the ordinary sense of the word, as they are dry most of the time and only fill up at intervals of 10 years or more.

Lake Eyre, which lies 40 feet below sea level, has a thick salt crust over the southern part, known as Madigan Gulf. It was this salt crust which led to its selection by Donald Campbell for his recent attempt on the Land Speed Record with Bluebird, despite its remote situation and the difficulty of getting there. Two things influenced the choice: one was that a course of up to 18 miles in length could be marked out, whereas the maximum now available in Utah is about 10 miles, and the other was the nature of the salt. Andrew Mustard, the Dunlop technician who had accompanied Campbell when the first Proteus Bluebird was wrecked at Bonneville, found that in some parts of Madigan Gulf the salt was heavily intermixed with sand, deposited on it when the surface was damp, a circumstance which normally occurs, strangely enough, during the heat of the afternoon. After removal of a thin layer of pure salt crystals, the brown surface exposed gave a coefficient of adhesion of up to 0.85, whereas the best figure recorded at Utah was 0.65.

Tire adhesion is one of the vital factors in this form of record breaking, because as speed increases, more and more of the available tire thrust is spent in overcoming air resistance so that less remains to provide acceleration or to maintain directional stability. It follows that the higher the speed, the less the rate of acceleration can be without danger of wheelspin and loss of control. That means, in its turn, that you must have a long acceleration run, during which the acceleration rate must be decreased as the speed rises.

Stopping a turbine-powered car also presents quite a problem, as there is practically no overrun resistance: The brakes have to absorb close to 5 million lb-ft of energy in a single stop from 450 mph, and in doing so, the surface temperature of the discs comes very close to the melting point. The rate of heat generation is so enormous that air-cooling has little effect.

So, despite all the difficulties in store, the possibility of getting 18 miles of high-quality surface seemed too good to miss. However, there was one snag. The surface, though generally flat, was dotted here and there with salt "islands," formed either by local upheaval of the crust in areas up to 30 yards long and perhaps half that width, or by incrustation of objects such as small branches or even dead rabbits. The average rainfall thereabouts is 5 inches a year, so surface water is all but nonexistent. Salt is difficult stuff to move, and after various abortive experiments the only satisfactory way of removing the large islands was found to be by milling them off with a rotary milling cutter, pulled at very slow speed behind a tractor. Mapping out the course which contained the fewest islands was not easy, and after one false start, another course termed the Bonython run (after Warren Bonython, one of the few authorities on the lake) was marked out.

Meanwhile, the South Australian Government weighed in with some much-needed support, first by grading 35 miles of road from Marree, the end of the standard-gauge section of the railway from Port Augusta, to Muloorina sheep station (ranch to you), then another 30 miles to the shore of the lake, which is where the transport problem really became difficult. As with most

salt lakes, the crust is thickest at the center (up to 12 inches in Madigan Gulf) and peters out to nothing at the edges. Underlying the crust is water-saturated blue mud with practically no sustaining power, and it was necessary to build a 400-yard causeway out from the shore to reach salt thick enough to carry 10-ton loads in safety. This job was done by a government road-making unit.

The government graders then started clearing the surface salt off the Bonython run, and trouble started almost immediately. One grader broke through the surface and left a gaping hole after it was extricated. Then, of all unexpected things, rain fell, about 1.25 inches of it, flooding the newly-graded run and ruining most of the work. Finally, a trailer picking up loose salt from a milled-off island broke through, and the effects of getting it out showed that the whole area where the island had been was dangerously thin.

A decision was reluctantly made by Campbell and David Wynne-Morgan, the project controller, that this runway was too dangerous for the record attempt, and another one had to be selected. Unfortunately, by this time the graders had been ordered away for repairs to public "roads” which had been badly affected by the rain, which has almost never been known to fall in the months of April or May. A further menace also appeared on the horizon, when water from very heavy rain in Queensland was reported to be approaching through rivers at the northern end of the lake, and nobody knew quite when this would arrive and cause general

flooding.

Shortly after Easter, the whole of the equipment and personnel concerned had arrived in the area by rail, road, and air.

Besides Bluebird, transported from Marree on a low-loader, there were five Fordson tractors with various attachments, including two Howard salt-millers; two Commer 5-ton truck;, a Humber Super Snipe car for tire adhesion tests; several Commer vans for refueling and carrying radio equipment; and a host of Land Rovers used for servicing Bluebird, running around generally and for transporting the British Petroleum film unit; plus several other assorted vehicles belonging to reporters and photographers.

All told, there were some 80 men at Lake Eyre, either in the houses or in caravans. Then a mechanized unit of the army and a detachment of police arrived, bringing the total up to around 150, which later swelled up to over 200, making the problem of food supply somewhat tricky when the road south became impassable on two occasions. The post office had also established a temporary radio station, linking us with Adelaide, but for most of the time atmospheric disturbances made this line sound as if one were talking in the middle of a parrot house.

Father

and son, a taste for speed. Donald got the bug first hand from Sir

Malcolm - as seen in the photograph above. They both went after the

ultimate prizes with serious machinery, and shook the world with their

achievements. Gina

Campbell took up the mantle first hand from her father Donald, but

suffered a near fatal flip at a lower level, drawing a close to plans

for ultimate victories. Don

Wales got his taste for the limelight third in line. That dilution

of the bloodline may account for the abridged goals; many third party

projects. When will another Campbell rise to take on the ultimate

challenges.

Donald

crashed the CN7 at Bonneville, as per the wreckage above, escaping with serious

injuries to try another day. The difference between Sir Malcolm and

Donald, is that his father began his motor-sport career as a racing

driver, so developing his handling skill level. While it is probably

true to say that there is a lesser skill level required from land and

water speed record drivers (where the craft could be radio controlled in

some cases), the experience from actual competition is a bonus, that

possibly explains why Sir Malcolm did not have any serious incidents.

The site of the first base camp was about 5 miles from the causeway, on firm salt near a graded landing ground constantly used by two Piper aircraft. Bluebird was taken out from Muloorina on a semi trailer, attached to an ex-wartime Ford 4x4 prime mover. After a few miles, this decrepit device lost its motive power and the whole lot was towed the rest of the way (often through sand up to 8 inches deep) by an Army wrecker, the 30-mile trip taking about 5 hours. The car was unloaded via a salt ramp with steel girders laid on top, then housed in a large tent, with a workshop alongside. A dump of various grades of fuel and oil also had been established at this spot, which seemed ideal until a few days later, when rain fell again. Even more fell at Muloorina, which became temporarily isolated. Then when the base camp itself became covered by about 2 inches of water, Donald decided to move the car back to shore for safety. He drove it back to the causeway (by then seriously softened by water), where it stayed in splendid isolation for some days. At this stage, there was sometimes up to 2 inches of water on the salt as far as the eye could see. This would almost disappear in a few hours if the wind was in the south, then reappear when the wind changed.

Following the abandonment of the Bonython run, a new course was marked out and work commenced on it. Unfortunately, this lay on an area mainly composed of white salt, and several test strips were prepared by various methods so that Andrew Mustard could determine their relative effectiveness. This was done by means of an Elfin racing car, a vehicle built in

Adelaide for Formula Junior events, powered with a 1500-cc Ford engine which gave it a top speed of around 140 mph. The tires were of the same construction and material as those of the Bluebird, but built to half-scale. The testing method used was to lock all four wheels with the brakes at maximum velocity, taking the deceleration figure from a recording Tapley meter.

As the northern floods still seemed to be a menace, time was becoming precious and they had to discover the quickest method of obtaining the best result. This was found to be by dragging

steel girders over the surface at about 5 mph behind the tractors.

Actually, two courses were marked out, one 10 miles long for initial low-speed runs up to about 200 mph and another 15 miles long for faster runs and the actual record. This entailed dragging a total length of 25 miles for a width of 80 yards, and naturally took some time. Also, a large salt island had to be milled off the middle of the practice run, which operation took nearly two days, as over 50 tons of salt had to be cut, picked up in the trucks, and carried some distance away. As Ken Norris, the designer, wanted the surface to be level to within 0.25 inches in 100 feet, some careful work with a level was required. By the time the island was leveled off, the salt under it was again becoming thin and weak, but not enough to prevent the strip being used for a couple of practice runs of up to 240 mph.

These runs also enabled the “turn-around” drill to be gone through thoroughly, which was very necessary. It takes a fair bit of coordination to change four wheels, refuel, recharge the air cylinders for brakes and the driver’s breathing air, and generally check everything over before the return run, all within a time limit of one hour. They also enabled some rather disgruntled press photographers to get some pictures and gave the police a chance to try out their methods of controlling the crowd, which undoubtedly would have arrived by car and plane if the record actually had been attempted. The runs also helped Ken Norris assess the effect of bumps of known height, by means of recording accelerometers mounted in the car.

All told, eight runs were made on the practice course, during which time the final course was being completed by dragging and milling off several salt islands of assorted sizes, but just as the 15 miles were practically completed, three weeks after Campbell had arrived, rain again fell, covering part of this run with water. However, Campbell took the car out in a strong side wind gusting to 25 knots, and with the fuel control set to provide only 25 percent torque, accelerated to 170 mph in 1 mile and 240 before the third mile, but then had to throttle back owing to the presence of surface water. Heavy rain also fell some miles away, bringing with it a distinct possibility that the Muloorina station would come down in a flood and cut all communication between the lake, the station, and the road south toward Adelaide.

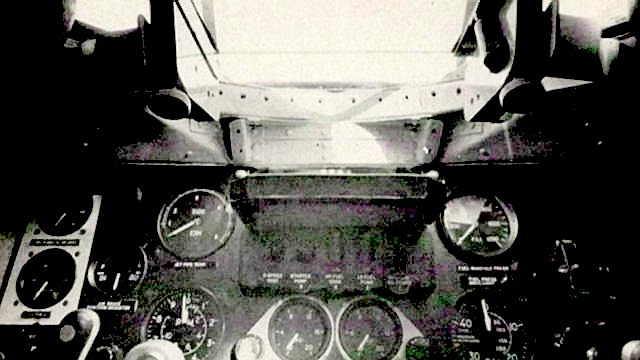

The

instruments as they were in 1963

The intention was to increase the throttle setting to 40 percent torque on the 14th for some quicker runs, and possibly go for the record in four or five more days, but such was not to be. The course was still under water on that day and the weather forecast was so gloomy that Campbell decided that night, in the interests of safety, to get the Bluebird and all heavy equipment off the

salt.

This operation was conducted at midnight, Campbell driving the car for some 6 miles in a circular course, guided only by the headlights of other vehicles, then through several inches of water up over the muddy end of the causeway on to comparatively dry land. The repeated falls of rain water had softened the salt near the causeway considerably and in the darkness several vehicles broke through and were left until daylight.

Getting these de-bogged and the rest of the lighter equipment off next day was quite a problem, as the entire area near the causeway end was breaking up, but eventually, besides Bluebird, there were 16 trucks, vans, and cars, 5

tractors, 8 trailers, and a whole heap of assorted gear on shore. Campbell’s insistence on getting off was not thought highly of by some at the time, but the decision was a wise one. Had the evacuation been left for another day, some of the stuff might still be there.

Even so, the problem was not over. The road in to Muloorina now was so bad that even the Army’s 6x6 trucks, with chains on all wheels, could not get through the first 3 miles, though they did succeed in churning up the mud so badly that nothing else could get through, either. Fortunately, the weather cleared and in a day’s time it was possible, but only just, for tractors and

Land Rovers to get through, and then the big evacuation started; even then, it took several hours to travel the 30 miles. While this was going on, another ramp was constructed from sand, with the girders laid on top, in order to load Bluebird on to the Ford semi trailer, and on Saturday, May 18, the journey in to Muloorina commenced, along a track largely composed of mud and ruts anywhere up to 18 inches deep.

The equipage, again towed by the Army wrecker, reached the station at 4:00 pm, at which time the crossing over the Frome was dry. Eight hours later, the threatened flood arrived, and only a couple hours after that, the water was nearly half a mile wide and about 10 feet deep in the center. As the track south toward civilization also traversed the river at a point 2 miles downstream, the entire Bluebird team and vehicles, plus the Army and police detachments, were marooned on the station for some days, although quite a number were flown out, as the airstrip was well above water level.

The Bluebird’s main attendants, Ken Norris, Leo

Villa, and Maurice Parfitt, stayed with the car to get the salt out of her system, and there she still is, awaiting further developments. What these will be, no one is quite sure. The salt on Lake Eyre will not be fit for any serious record-breaking until about February next year at the earliest, and possibly not then if the next “wet” season is really wet. At the time of this writing, Campbell is looking for other possible sites, but even if there are any, the nearest would be over 1000 land miles away and even more inaccessible than Lake Eyre, which, but for this heartbreaking stroke of bad luck, would have been as good a place as you could find anywhere.

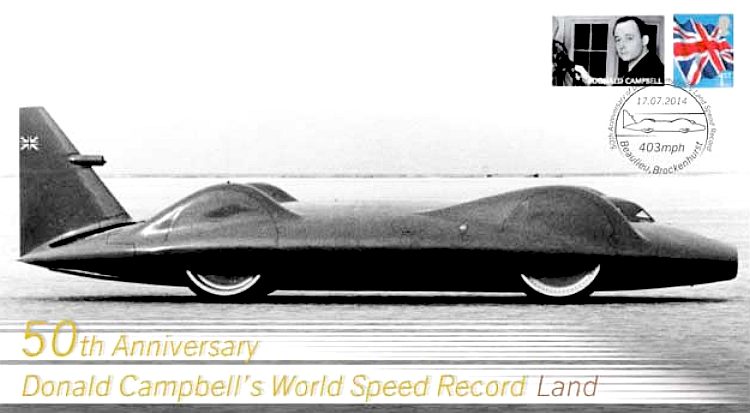

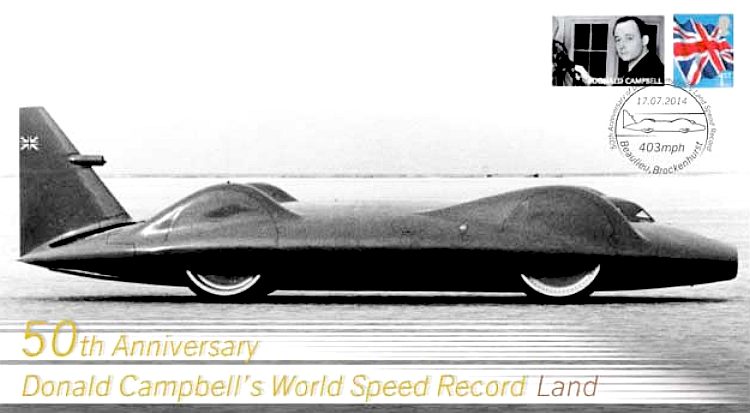

LAKE EYRE 1964

Campbell and his team returned to Lake Eyre in 1964, with sponsorship from Australian oil company Ampol, but the salt surface never returned to the promise it had held in 1962 and Campbell had to battle with CN7 to reach record speeds (over 400 mph or 640 km/h). After more light rain in June, the lake finally began to dry enough for an attempt to be made. On July 17, 1964, Campbell set a record of 403.10 mph (648.73 km/h) for a four-wheeled vehicle (Class A). Campbell was disappointed with the record speed as the vehicle had been designed for 500 mph (800 km/h). CN7 covered the final third of the measured mile at an average of 429 mph (690 km/h), peaking as it left the measured mile at over 440 mph (710 km/h). Had the salt surface been hard and dry, and the full 15 mile length originally envisaged, there can be no doubt that CN7 would have set a record well in excess of 450 mph (720 km/h) and perhaps close to her design maximum of 500 mph (800 km/h), a speed that no other wheel driven car has approached.

Campbell commissioned the author John Pearson to chronicle this attempt, with the resultant critically acclaimed book Bluebird and the Dead Lake, published by Collins in 1965.

Tonia

Bern and Donald Campbell

POST RECORD CELEBRATIONS

To celebrate the record, Campbell drove CN7 through the streets of the South Australian capital, Adelaide, to a presentation at city hall before a crowd of in excess of 200,000 people. CN7 was then displayed widely in Australia and the UK after her return in November 1964.

In June 1966, CN7 was demonstrated at RAF Debden in Essex, with a stand in driver, Peter Bolton. He crashed the car during a medium speed run, causing damage to her bodywork and front suspension. The car was patched up and Campbell ran her at a much lower speed than he intended. Campbell continued with his plans for the rocket-powered car Bluebird Mach 1.1 with a view to raising the LSR towards Mach 1. In January 1967, he was killed in his water-speed record jet hydroplane Bluebird K7.

CN7 was eventually restored in 1969, but has never fully run again. In 1969, Campbell's widow, Tonia Bern-Campbell negotiated a deal with Lynn Garrison, President of

Craig Breedlove and Associates, that would see Craig Breedlove run Bluebird on Bonneville's Salt Flats. This concept was cancelled when the parallel Spirit of America supersonic car project failed to find

support.

It became a permanent exhibit at the National Motor

Museum, Beaulieu, England in 1972, and is still on display there.

In January 2012, Adrian Newey, F1 racing car designer for Red

Bull, and previously Williams GP and

McLaren praised Bluebird CN7 in Racecar Engineering Magazine:

“ I think in terms of one of the biggest advances made, although it was not strictly speaking a racing car, was Bluebird. Arguably for its time it was the most advanced vehicle.’

The Bluebird Proteus CN7 was the car that Donald Campbell used to set a record of 403.1mph in July, 1964, the last outright land speed record car that was wheel driven. It was a revolutionary car that featured an advanced aluminium honeycomb chassis, featured fully

independent suspension and four-wheel drive. It also had a head-up display for Campbell.

A

technological

masterpiece of its day that didn't get the chance to give its all

‘It was the first car to properly recognise, and use, ground effects,’ says Newey. ‘The installation of the jet turbines is a nightmare, and it was constructed using a monocoque working with a lot of lightweight structures. It was built in a way that you build an

aircraft, but at the time motor racing teams weren’t doing that.’

Unsurprisingly,

the CN7 is a popular model for collectors

The car featured a Bristol-Siddeley Proteus gas turbine engine that developed over 4,000bhp. It was a two-spool, reverse flow gas turbine engine that was specially modified to have a drive shaft at each end of the engine, to separate fixed ratio gearboxes on each axle. It was designed to do 500mph, but surface conditions, brought about by adverse weather in 1963 and 1964, meant that its fastest recorded time was nearly 100mph short of its hypothetical capability. It is interesting to note that, should an exact replica be built today, and it did achieve its potential, it

could beat the existing record of 470.444mph set by Don Vesco’s Vesco Turbinator in 2001, and still be the fastest wheel-driven car

today, but possibly not on those huge Dunlop tyres, which caused so many

balance and wear problems.

The

BlueBird CN7 (Campbell

Norris 7) at the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu

SIR

MALCOLM CAMPBELL'S BLUE BIRDS

Sunbeam

Napier

Lion

Rolls

Royce

K3

K4

DONALD

CAMPBELL'S BLUEBIRDS

K7

CN7

CNM8

Jetstar

The

Blue Bird K4 was fitted with a jet engine - the beginning - and the jet

engined Blue Bird K7 in which Donald Campbell CBE met his fate. RIP

LINKS

Daily

Record Scotland unseen photographs of Donald Campbells Bluebird CN7

http://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/pictures-unseen-photos-donald-campbells-3814300

5-million-dollar-failure-bluebird-in-australia-1963

http://www.roadandtrack.com/racing/5-million-dollar-failure-bluebird-in-australia-1963

Bluebird

speed records

Bluebird

team racing

Bluebird-Proteus_CN7

http://www.bluebirdspeedrecords.com/

http://www.bluebirdteamracing.net

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bluebird-Proteus_CN7

|