|

The

morning sunshine catches Donald in the eye as he prepares for a run that

will see him in the halls of fame, possibly forever, as the man who

captured the land and water speed records in the same year: 1964.

1964 -

CAMPBELL SPEEDS TO A DOUBLE RECORD

When

Donald

Campbell

broke the world water speed

record at Lake Dumbleyung, he became the first man to

break the world land and water speed records in the same year.

He

reached an average speed of 276.33mph (444.71km/h) in his speedboat,

Bluebird, on this afternoon on Lake Dumbleyung in Perth, Western Australia.

The

feat shattered his previous world record of 260.35mph (418.99km/h) at Lake

Coniston, Cumbria, in 1959. It took a while for the news to filter back,

but the world gasped as the son that Sir

Malcolm had forbidden from the sport,

finally put his father in the shade. And why was that? Because DC was a

man of vision with the guts to see his aspirations through. It was

not easy, first he had to secure the land speed record, the story of

which is seen below using a mix of contemporary and recent articles by

way of review.

Donald

sporting an overall bearing a blue bird logo. The color blue and bird

emblem have been adopted by BMS Ltd for their land and water vehicle

developments, partly in tribute to DC and his father MC - not

forgetting, or course, the Belgian playwright who first made the bird

famous with his splendid productions: Maurice

Maeterlinck.

ADELAIDE

NOW - JULY 16 2014 - Bluebird land-speed record at Lake Eyre turns 50 today

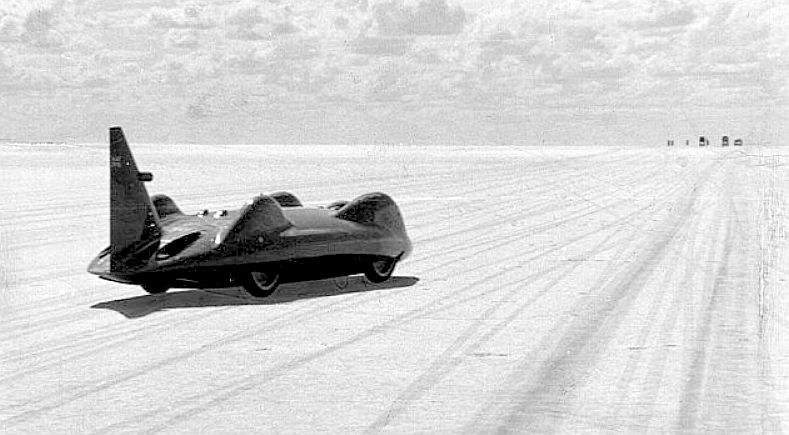

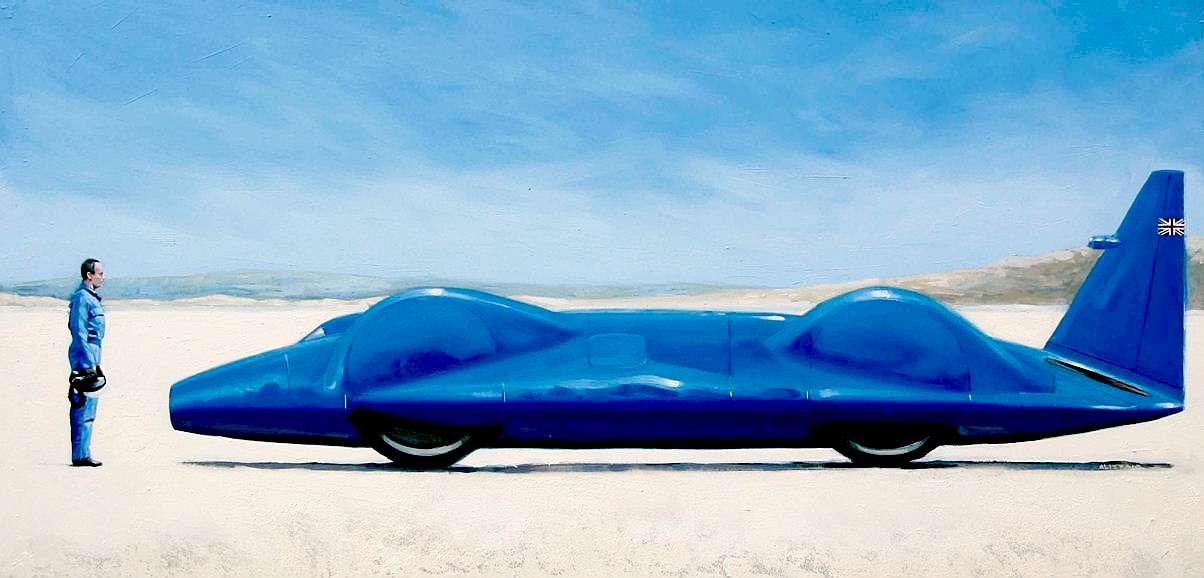

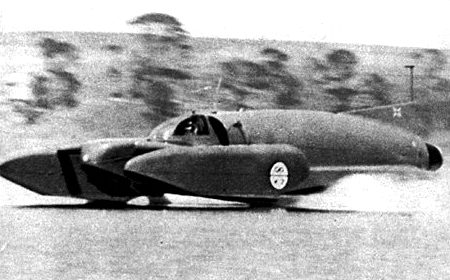

BY 8.10am, it was all over. The land-speed record was in the bag, Donald Campbell was returned as the fastest man on the planet, Bluebird was the quickest car and South Australia’s Lake Eyre salt pans in the state’s Far North were forever etched as the vital ingredient that helped make it happen.

Fifty years ago today, at precisely 8.10am, Englishman Campbell became the first man to break the 400 mile per hour limit in a

wheel-driven vehicle.

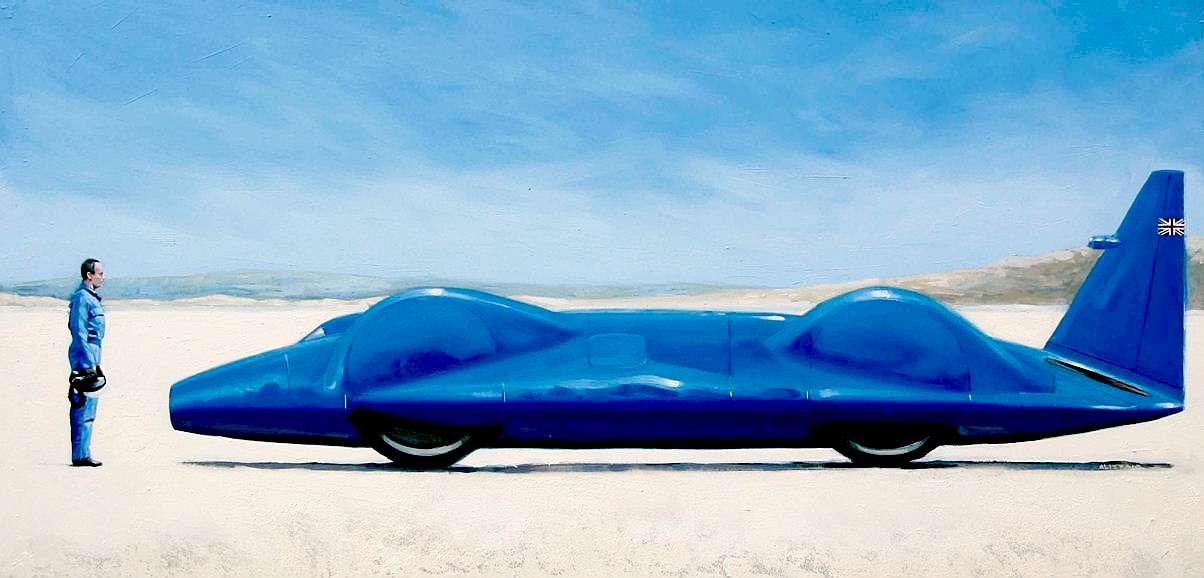

Donald Campbell and The Bluebird

en route to Lake Eyre for world land speed record attempt in July 1964.

On July 17, 1964, with back-to-back passes in opposite directions near Muloorina Station, Campbell registered an average speed of 403.1mph (648.7km/h).

At the time - even though a year earlier American Craig Breedlove in his three-wheeled, jet-engine powered

Spirit of America had registered a faster 407.4mph

- official records recognized only wheel-driven vehicles.

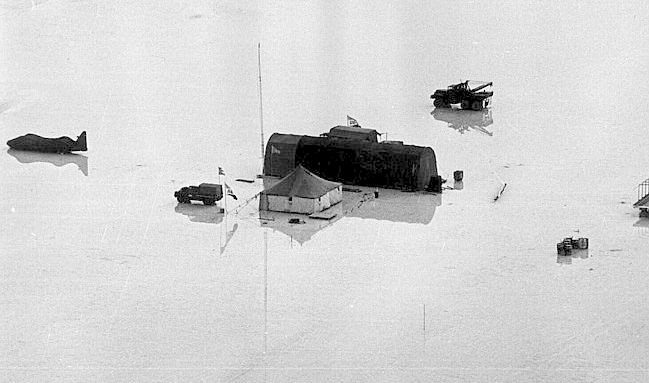

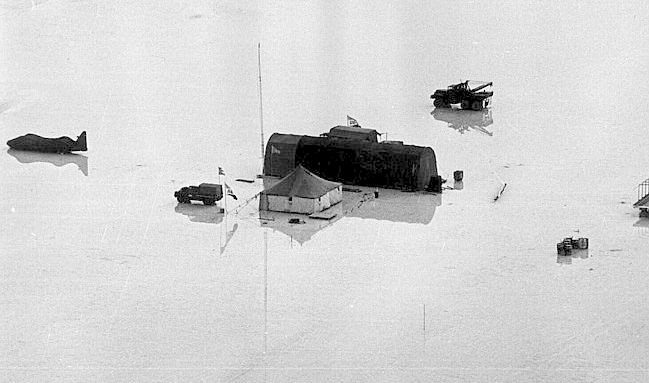

The

'Bluebird Team' camped out on the salt at Lake Eyre in three large

tents. The proteus jet powered car is seen on the left with the trailer

in the picture above to the far right.

Campbell’s first pass began at 7.17am when he left his headquarters. It took almost 7km to work up to full speed. At the average speed of 403.1mph, it took just 8.9 seconds to chew up the “measure mile”. From there, Campbell had 11km to stop Bluebird for his maintenance crew to prepare for the reverse run.

Under strict rules, he had an hour to complete the return leg. By 8.10am, posting the same average time as his first run, Campbell had overtaken fellow Englishman

John Cobb’s previous record of 394.2mph (634.4km/h).

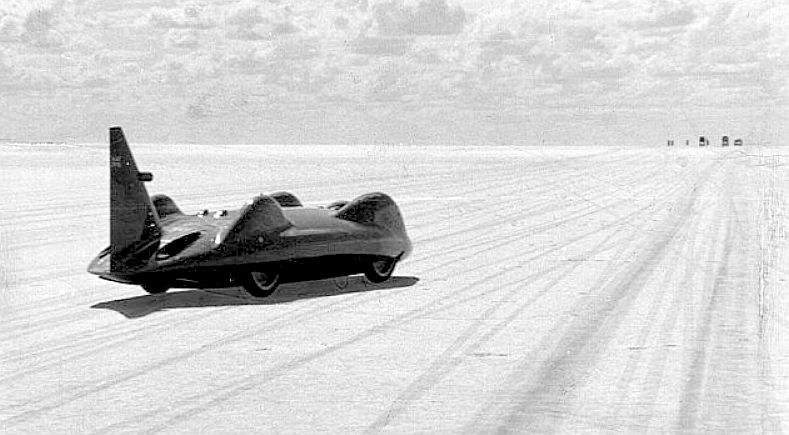

Bluebird

turns into the track for the return run within the hour, racing across the salt flats of Lake

Eyre before the temperature gets too hot.

Campbell had made a prior trial run at a lower velocity to gauge the

running.

Barely five weeks earlier, Beatle-mania had hit Adelaide when 300,000 fans of the

British supergroup spilt into the city streets to catch a glimpse of the Fab Four.

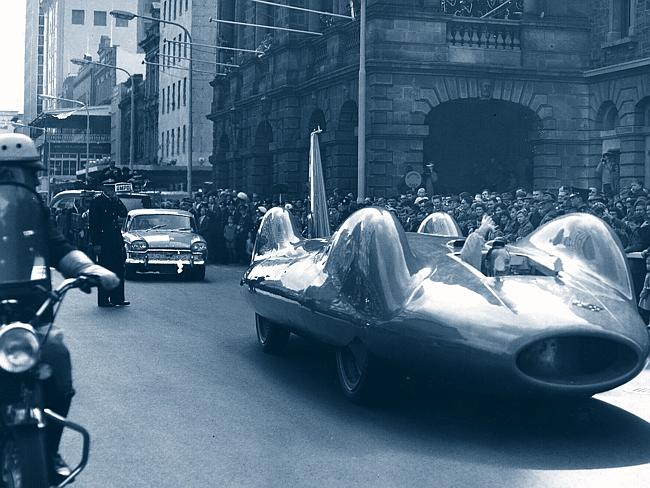

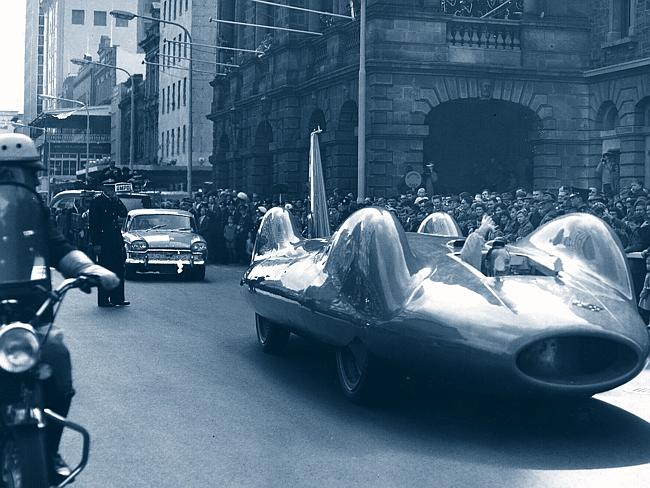

Campbell’s crowd didn’t quite topple Beatle-mania, but an estimated 200,000 people gathered in celebration to see him drive his sleek, four-tonne vehicle along King William St to the Town Hall on July 25, 1964.

Reports from the time suggest Campbell revved the engine to a huge roar, sending the crowd wild.

Campbell’s record, unlike its legacy, was only fleeting. By December

11 1964, less than five months after his Lake Eyre success, previously opposing regulatory federations agreed to open the record to any vehicle running on wheels.

On

the 27 October 1965 an American, Art

Arfon, drove

his jet car across Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah at an average speed of

536.71mph (863.75km/h). This moved the goal-post somewhat for any stiff

upper lipped Brit.

The

Bluebird CN7 parades through the Adelaide with

Campbell waving to fans on King William Street. A police escort was

provided for the speed king.

Campbell was already committed to becoming the first man to break both the land-speed and water speed records in the same year.

He achieved the double on December 31, when he clocked 276.3mph (444.7km/h) at

Lake Dumbleyung near Perth in his

Bluebird K7 boat.

Soon after, Campbell mapped out a three-year plan to build and race a rocket-powered vehicle capable of 840mph (1350km/h)

- named Bluebird Mach

1.1. In a bid to

publicize the record bid, he took one more shot at raising the water speed record, targeting 300mph (482km/h).

His dream of piloting the Bluebird Mach 1.1 would never materialise. On January 4, 1967, on his return run at England’s Lake Consiton, Campbell’s Bluebird K7 boat

flipped at an estimated 528km/h, instantly killing the speed ace.

Speed ace Donald Campbell’s Bluebird land-speed record at Lake Eyre

turned 50 on the 16th of July 2014. The water speed record component of

the "double" anniversary is December the 31st 2014.

Donald

Campbell parades his car past crowds in front of Adelaide Town Hall. A

huge crowd had gathered to see the blue car for themselves. This picture

is from the Advertiser's library.

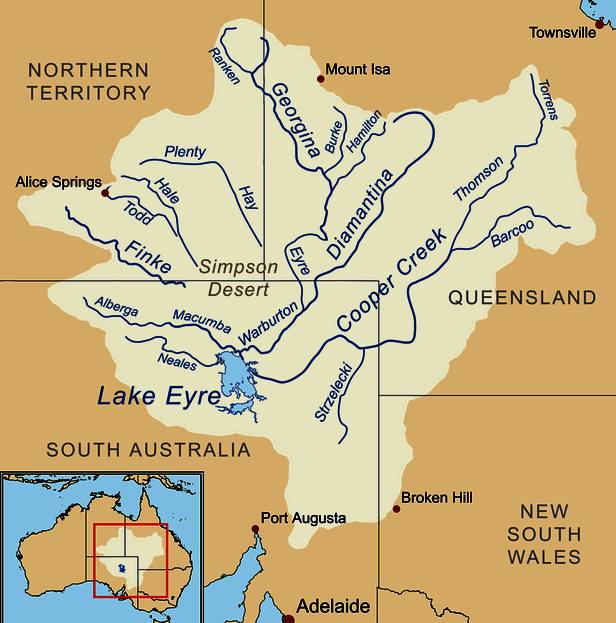

ROAD & TRACK OCTOBER 1963 - $5,000,000 FAILURE

Any good map of Australia shows a number of blue patches named Lake this or Lake that, the largest being Lake Eyre, lying nearly 500 miles north of Adelaide. However, none of these are lakes in the ordinary sense of the word, as they are dry most of the time and only fill up at intervals of 10 years or more.

Lake Eyre, which lies 40 feet below sea level, has a thick salt crust over the southern part, known as Madigan Gulf. It was this salt crust which led to its selection by Donald Campbell for his recent attempt on the Land Speed Record with Bluebird, despite its remote situation and the difficulty of getting there. Two things influenced the choice: one was that a course of up to 18 miles in length could be marked out, whereas the maximum now available in Utah is about 10 miles, and the other was the nature of the salt. Andrew Mustard, the Dunlop technician who had accompanied Campbell when the first Proteus Bluebird was wrecked at Bonneville, found that in some parts of Madigan Gulf the salt was heavily intermixed with sand, deposited on it when the surface was damp, a circumstance which normally occurs, strangely enough, during the heat of the afternoon. After removal of a thin layer of pure salt crystals, the brown surface exposed gave a coefficient of adhesion of up to 0.85, whereas the best figure recorded at Utah was 0.65.

Tire adhesion is one of the vital factors in this form of record breaking, because as speed increases, more and more of the available tire thrust is spent in overcoming air resistance so that less remains to provide acceleration or to maintain directional stability. It follows that the higher the speed, the less the rate of acceleration can be without danger of wheelspin and loss of control. That means, in its turn, that you must have a long acceleration run, during which the acceleration rate must be decreased as the speed rises.

Loading

and unloading a 30 foot car is no joke. A special trailer could be

covered with a canvas tarpaulin to protect the jet engine and paintwork

from the salt.

Stopping a turbine-powered car also presents quite a problem, as there is practically no overrun resistance: The brakes have to absorb close to 5 million lb-ft of energy in a single stop from 450 mph, and in doing so, the surface temperature of the discs comes very close to the melting point. The rate of heat generation is so enormous that air-cooling has little effect.

So, despite all the difficulties in store, the possibility of getting 18 miles of high-quality surface seemed too good to miss. However, there was one snag. The surface, though generally flat, was dotted here and there with salt "islands," formed either by local upheaval of the crust in areas up to 30 yards long and perhaps half that width, or by incrustation of objects such as small branches or even dead rabbits. The average rainfall thereabouts is 5 inches a year, so surface water is all but nonexistent. Salt is difficult stuff to move, and after various abortive experiments the only satisfactory way of removing the large islands was found to be by milling them off with a rotary milling cutter, pulled at very slow speed behind a tractor. Mapping out the course which contained the fewest islands was not easy, and after one false start, another course termed the Bonython run (after Warren Bonython, one of the few authorities on the lake) was marked out.

Meanwhile, the South Australian Government weighed in with some much-needed support, first by grading 35 miles of road from Marree, the end of the standard-gauge section of the railway from Port Augusta, to Muloorina sheep station (ranch to you), then another 30 miles to the shore of the lake, which is where the transport problem really became difficult. As with most salt lakes, the crust is thickest at the center (up to 12 inches in Madigan Gulf) and peters out to nothing at the edges. Underlying the crust is water-saturated blue mud with practically no sustaining power, and it was necessary to build a 400-yard causeway out from the shore to reach salt thick enough to carry 10-ton loads in safety. This job was done by a government road-making unit.

The government graders then started clearing the surface salt off the Bonython run, and trouble started almost immediately. One grader broke through the surface and left a gaping hole after it was extricated. Then, of all unexpected things, rain fell, about 1.25 inches of it, flooding the newly-graded run and ruining most of the work. Finally, a trailer picking up loose salt from a milled-off island broke through, and the effects of getting it out showed that the whole area where the island had been was dangerously thin.

A decision was reluctantly made by Campbell and David Wynne-Morgan, the project controller, that this runway was too dangerous for the record attempt, and another one had to be selected. Unfortunately, by this time the graders had been ordered away for repairs to public "roads” which had been badly affected by the rain, which has almost never been known to fall in the months of April or May. A further menace also appeared on the horizon, when water from very heavy rain in Queensland was reported to be approaching through rivers at the northern end of the lake, and nobody knew quite when this would arrive and cause general flooding.

A

quick wheel change in the baking Australian sun. DC as usual smoking a

cigar.

Shortly after Easter, the whole of the equipment and personnel concerned had arrived in the area by rail, road, and air.

Besides Bluebird, transported from Marree on a low-loader, there were five Fordson tractors with various attachments, including two Howard salt-millers; two Commer 5-ton truck;, a Humber Super Snipe car for tire adhesion tests; several Commer vans for refueling and carrying radio equipment; and a host of Land Rovers used for servicing Bluebird, running around generally and for transporting the British Petroleum film unit; plus several other assorted vehicles belonging to reporters and photographers.

All told, there were some 80 men at Lake Eyre, either in the houses or in caravans. Then a mechanized unit of the army and a detachment of police arrived, bringing the total up to around 150, which later swelled up to over 200, making the problem of food supply somewhat tricky when the road south became impassable on two occasions. The post office had also established a temporary radio station, linking us with Adelaide, but for most of the time atmospheric disturbances made this line sound as if one were talking in the middle of a parrot house.

The site of the first base camp was about 5 miles from the causeway, on firm salt near a graded landing ground constantly used by two Piper aircraft. Bluebird was taken out from Muloorina on a semi trailer, attached to an ex-wartime Ford 4x4 prime mover. After a few miles, this decrepit device lost its motive power and the whole lot was towed the rest of the way (often through sand up to 8 inches deep) by an Army wrecker, the 30-mile trip taking about 5 hours. The car was unloaded via a salt ramp with steel girders laid on top, then housed in a large tent, with a workshop alongside. A dump of various grades of fuel and oil also had been established at this spot, which seemed ideal until a few days later, when rain fell again. Even more fell at Muloorina, which became temporarily isolated. Then when the base camp itself became covered by about 2 inches of water, Donald decided to move the car back to shore for safety. He drove it back to the causeway (by then seriously softened by water), where it stayed in splendid isolation for some days. At this stage, there was sometimes up to 2 inches of water on the salt as far as the eye could see. This would almost disappear in a few hours if the wind was in the south, then reappear when the wind changed.

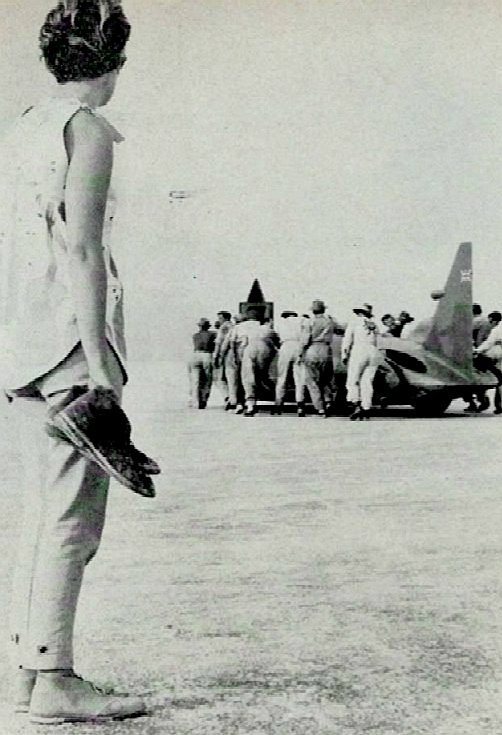

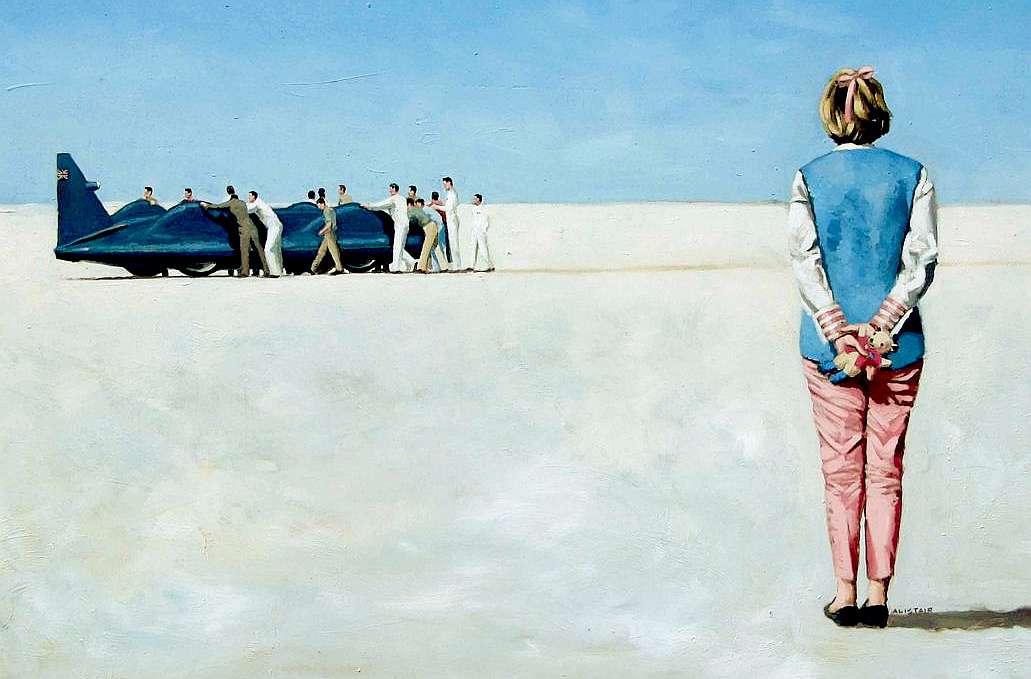

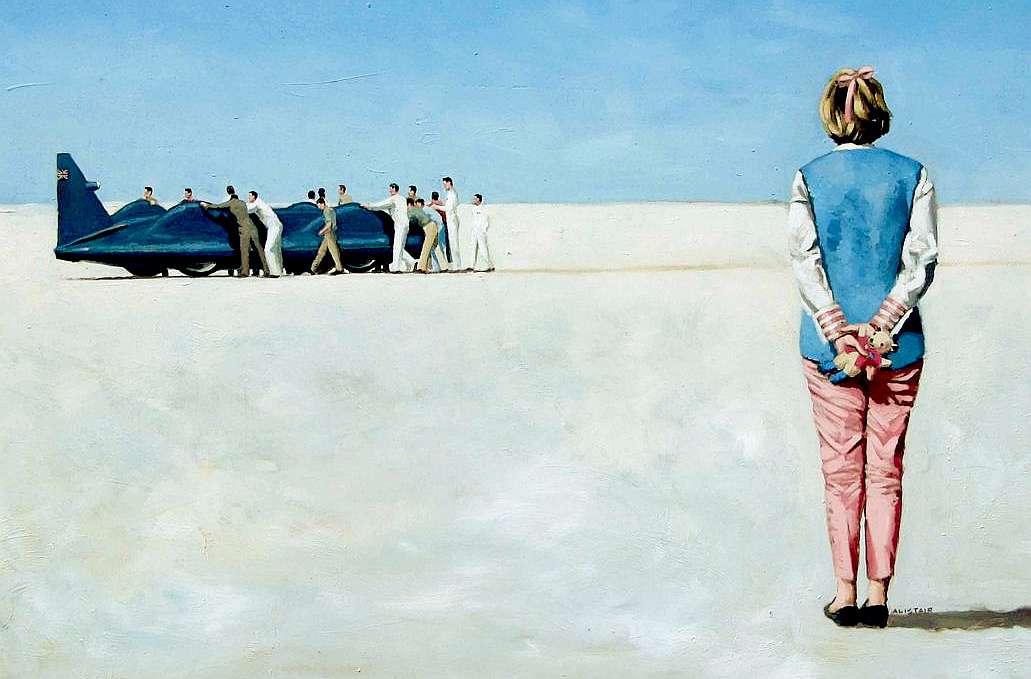

LEFT:

Looking on, Tonia Bern-Campbell watches from the sidelines as the 'circus'

prepare her husband's car for his land speed record run. RIGHT: A

painting, presumably inspired by this or other similar photographs of the

event, by Alister Little. Alistair began his artistic career in the film industry in 1994, focusing on model making and design. After three years in the film and television industries he turned to two dimensional art to train and work as a freelance commercial illustrator. Early commissions included an underground comic and graphic design work along with storyboard work for the advertising industry. Here he learnt the true value of a strong knowledge of draughtsmanship and his ability to render credible accurate figure work is the backbone of his work today.

In 2001, after four years almost exclusively working in markers and pencils

Alister started experimenting with paint and has not looked back. Alistair’s artistic influences are immediately evident. His great love of 20th century cinema, particularly film noir, dominates his style and his subject matter. His early experience in the

film industry taught him the technique of capturing a wider story in the confines of one still image. Each of Alistair’s paintings burst with cinematic tension, his models are carefully posed and dressed to play a well choreographed role within a cleverly lit backdrop.

Following the abandonment of the Bonython run, a new course was marked out and work commenced on it. Unfortunately, this lay on an area mainly composed of white salt, and several test strips were prepared by various methods so that Andrew Mustard could determine their relative effectiveness. This was done by means of an Elfin racing car, a vehicle built in Adelaide for Formula Junior events, powered with a 1500-cc Ford engine which gave it a top speed of around 140 mph. The tires were of the same construction and material as those of the Bluebird, but built to half-scale. The testing method used was to lock all four wheels with the brakes at maximum velocity, taking the deceleration figure from a recording Tapley meter.

As the northern floods still seemed to be a menace, time was becoming precious and they had to discover the quickest method of obtaining the best result. This was found to be by dragging

steel girders over the surface at about 5 mph behind the tractors.

Actually, two courses were marked out, one 10 miles long for initial low-speed runs up to about 200 mph and another 15 miles long for faster runs and the actual record. This entailed dragging a total length of 25 miles for a width of 80 yards, and naturally took some time. Also, a large salt island had to be milled off the middle of the practice run, which operation took nearly two days, as over 50 tons of salt had to be cut, picked up in the trucks, and carried some distance away. As

Ken

Norris, the designer, wanted the surface to be level to within 0.25 inches in 100 feet, some careful work with a level was required. By the time the island was leveled off, the salt under it was again becoming thin and weak, but not enough to prevent the strip being used for a couple of practice runs of up to 240 mph.

Andrew

Mustard inspects the salt build up after a trial run. Soil mechanics is a branch of engineering mechanics that describes the behavior of soils. It differs from fluid mechanics and solid mechanics in the sense that soils consist of a heterogeneous mixture of fluids (usually air and water) and particles (usually clay, silt, sand, and gravel) but soil may also contain organic solids, liquids, and gasses and other matter. Along with rock mechanics, soil mechanics provides the theoretical basis for analysis in geotechnical engineering, a subdiscipline of civil engineering, and engineering geology, a subdiscipline of geology. Soil mechanics is used to analyze the deformations of and flow of fluids within natural and man-made structures that are supported on or made of soil, or structures that are buried in soils. Example applications are building and bridge foundations, retaining walls, dams, and buried pipeline systems. Principles of soil mechanics are also used in related disciplines such as engineering geology, geophysical engineering, coastal engineering, agricultural engineering, hydrology and soil physics.

These runs also enabled the “turn-around” drill to be gone through thoroughly, which was very necessary. It takes a fair bit of coordination to change four wheels, refuel, recharge the air cylinders for brakes and the driver’s breathing air, and generally check everything over before the return run, all within a time limit of one hour. They also enabled some rather disgruntled press photographers to get some pictures and gave the police a chance to try out their methods of controlling the crowd, which undoubtedly would have arrived by car and plane if the record actually had been attempted. The runs also helped Ken Norris assess the effect of bumps of known height, by means of recording accelerometers mounted in the car.

All told, eight runs were made on the practice course, during which time the final course was being completed by dragging and milling off several salt islands of assorted sizes, but just as the 15 miles were practically completed, three weeks after Campbell had arrived, rain again fell, covering part of this run with water. However, Campbell took the car out in a strong side wind gusting to 25 knots, and with the fuel control set to provide only 25 percent torque, accelerated to 170 mph in 1 mile and 240 before the third mile, but then had to throttle back owing to the presence of surface water. Heavy rain also fell some miles away, bringing with it a distinct possibility that the Muloorina station would come down in a flood and cut all communication between the lake, the station, and the road south toward Adelaide.

The intention was to increase the throttle setting to 40 percent torque on the 14th for some quicker runs, and possibly go for the record in four or five more days, but such was not to be. The course was still under water on that day and the weather forecast was so gloomy that Campbell decided that night, in the interests of safety, to get the Bluebird and all heavy equipment off the salt.

This operation was conducted at midnight, Campbell driving the car for some 6 miles in a circular course, guided only by the headlights of other vehicles, then through several inches of water up over the muddy end of the causeway on to comparatively dry land. The repeated falls of rain water had softened the salt near the causeway considerably and in the darkness several vehicles broke through and were left until daylight.

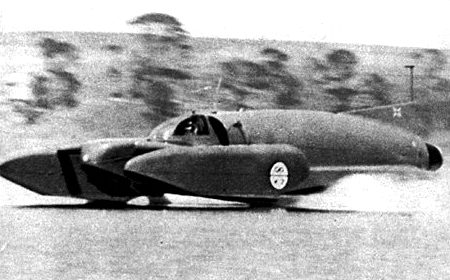

In

the 1960s the only way that news was spread was by movie reel coverage,

sometimes played at cinemas before a feature film. Television coverage

with digital equipment has changed all that. British Pathe were the news

leaders at the time. In this picture, Leo Villa

is on the left, and a young Ken Norris is

crouched on the right.

Getting these de-bogged and the rest of the lighter

equipment off next day was quite a problem, as the entire area near the causeway end was breaking up, but eventually, besides Bluebird, there were 16 trucks, vans, and cars, 5 tractors, 8 trailers, and a whole heap of assorted gear on shore. Campbell’s insistence on getting off was not thought highly of by some at the time, but the decision was a wise one. Had the evacuation been left for another day, some of the stuff might still be there.

Even so, the problem was not over. The road in to Muloorina now was so bad that even the Army’s 6x6 trucks, with chains on all wheels, could not get through the first 3 miles, though they did succeed in churning up the mud so badly that nothing else could get through, either. Fortunately, the weather cleared and in a day’s time it was possible, but only just, for tractors and Land Rovers to get through, and then the big evacuation started; even then, it took several hours to travel the 30 miles. While this was going on, another ramp was constructed from sand, with the girders laid on top, in order to load Bluebird on to the Ford semi trailer, and on Saturday, May 18, the journey in to Muloorina commenced, along a track largely composed of mud and ruts anywhere up to 18 inches deep.

The equipage, again towed by the Army wrecker, reached the station at 4:00 pm, at which time the crossing over the Frome was dry. Eight hours later, the threatened flood arrived, and only a couple hours after that, the water was nearly half a mile wide and about 10 feet deep in the center. As the track south toward civilization also traversed the river at a point 2 miles downstream, the entire Bluebird team and vehicles, plus the Army and police detachments, were marooned on the station for some days, although quite a number were flown out, as the airstrip was well above water level.

The Bluebird’s main attendants, Ken Norris, Leo Villa, and Maurice Parfitt, stayed with the car to get the salt out of her system, and there she still is, awaiting further developments. What these will be, no one is quite sure. The salt on Lake Eyre will not be fit for any serious record-breaking until about February next year at the earliest, and possibly not then if the next “wet” season is really wet. At the time of this writing, Campbell is looking for other possible sites, but even if there are any, the nearest would be over 1000 land miles away and even more inaccessible than Lake Eyre, which, but for this heartbreaking stroke of bad luck, would have been as good a place as you could find anywhere.

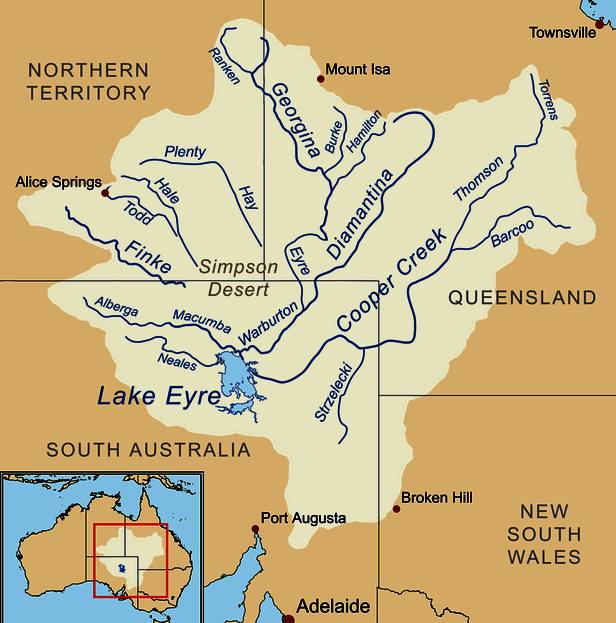

LAKE

EYRE

Lake Eyre, (pronounced "air") is officially known as Kati

Thanda-Lake Eyre in Australia. The lake is the lowest natural point in Australia, at approximately 15 m (49 ft) below sea level (AHD), and, on the rare occasions that it fills,

it becomes the largest lake in Australia and 18th largest in the world. The temporary, shallow lake is the depocenter of the vast Lake Eyre Basin and is found in South Australia, some 700 km (435 mi) north of

Adelaide. The lake was named in honour of Edward John Eyre, who was the first

European to see it, in 1840. The lake's official name was changed in December 2012 to combine the name "Lake Eyre" with the indigenous name, Kati Thanda. Native title over the lake and surrounding region is held by the Arabana people.

Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre National Park is located 60km east of William Creek. Access is via the Oodnadatta Track and Halligan Bay Public Access Route. Kati Thanda-Lake Eyre National Park is also 95km north west of Marree. Access is via Muloorina Station and Level Post Bay Public Access Route.

GEOGRAPHY

Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre is located in the deserts of central Australia, in northern South Australia. The Lake Eyre Basin is a large endorheic system surrounding the lakebed, the lowest part of which is filled with the characteristic salt pan caused by the seasonal expansion and subsequent evaporation of the trapped waters. Even in the dry season there is usually some water remaining in Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre, normally collecting in over 200 smaller sub-lakes within its margins. The lake was formed by aeolian processes after tectonic upwarping occurred to the south subsequent to the end of the Pleistocene epoch.

During the rainy season the rivers from the north-east part of the Lake Eyre Basin (in outback (south-west and central) Queensland) flow towards the lake through the Channel Country. The amount of water from the monsoon determines whether water will reach the lake and if it does, how deep the lake will get. The average rainfall in the area of the lake is 100 to 150 mm per year.

This

is a satellite picture of the Lake. Covering an area 144km long and 77km wide, Lake Eyre is an extensive salt sink which derives its mineralisation from the evaporation of floodwaters over thousands of years. Water from its three-state catchment area covers the lake about once every eight years. The lake has only filled to capacity three times in the last 150 years.

The −15 m (−49 ft) altitude usually attributed to Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre refers to the deepest parts of the lake floor, in Belt Bay and the Madigan Gulf. The shoreline lies at −9 m (−30

ft). The lake is the area of maximum deposition of sediment in the Lake Eyre Basin.

Lake Eyre is divided into two sections which are joined by the Goyder Channel. These are known as Lake Eyre North, which is 144 km in length and 65 km wide and Lake Eyre South, which measures 65 by 24 km. The salt crusts are thickest (up to 50 cm) in the southern Belt Bay, Jackboot Bay and Madigan Gulf sub-basins of Lake Eyre North.

Since 1883 proposals have been forwarded to flood Lake Eyre with seawater brought to the basin via canal or pipeline. The purpose was, in part, to increase evaporation and thereby increase rainfall in the region downwind of an enlarged Lake Eyre. Due to the basin's low elevation below sea level and the region's high annual evaporation rate (between 2,500 and 3,500mm) such schemes have generally been considered impractical as it is likely that accumulation of salt deposits would rapidly block the engineered channel.

Seasonal rainfalls attract waterbirds such as Australian pelicans, silver gulls, red-necked avocets, banded stilts and gull-billed terns. When the lake floods it becomes a breeding site for enormous numbers of waterbirds, especially species that appear to be tolerant of salinity.

The best way to see Lake Eyre and take in its vastness is from the air. Scheduled scenic flights provide spectacular views across the park and showcase the seasonal wildlife.

FLOODING

Typically a 1.5 m (5 ft) flood occurs every three years, a 4 m (13 ft) flood every decade, and a fill or near fill a few times a century. The water in the lake soon evaporates with a minor or medium flood drying by the end of the following summer. Most of the

water entering the lakes arrives via Warburton River.

In strong La Niña years the lake can fill. Since 1885 this has occurred in 1886–1887, 1889–1890, 1916–1917, 1950, 1955, 1974–1977, and

1999-2001, with the highest flood of 6 m (20 ft) in 1974. Local rain can also fill Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre to 3–4 m (10–13 ft) as occurred in 1984 and 1989. Torrential rain in January 2007 took about six weeks to reach the lake but put only a small amount of water into it.

When recently flooded the lake is almost fresh and native freshwater fish, including bony bream (Nematolosa erebi), the Lake Eyre Basin sub-species of golden perch (Macquaria ambigua) and various small hardyhead species (Craterocephalus) can survive in it. The salinity increases as the 450 mm (18 in) salt crust dissolves over a period of six months resulting in a massive fish kill. When over 4 m (13 ft) deep the lake is no more salty than the sea, but salinity increases as the water evaporates, with saturation occurring at about a 500 mm (20 in) depth. The Lake takes on a pink hue when saturated due to the presence of beta-carotene pigment caused by the algae Dunaliella

salina.

Even when the lake is not entirely filled, it’s an amazing sight. The water brings

fish and birdlife, and the interaction between the water and an algae called Dunaliella salina endows the landscape with a pink hue. The best view is from an aircraft, but you can also take a 4WD tour around the edge. The indigenous land owners, the Arabanna people, ask that visitors respect the waterway and not take recreational craft out on it. Today,

drones

might undertake surveys, film the terrain and provide other scientific

data from onboard instruments.

WILDLIFE

Phytoplankton in the lake includes Nodularia spumigena and a number of species of Dunaliella.

The lake has been identified by 'Bird Life International' as an Important Bird Area (IBA) because, when flooded, it supports major breeding events of the Banded Stilt and Australian Pelican, as well as over 1% of the world populations of Red-necked Avocets, Sharp-tailed Sandpipers, Red-necked Stints, Silver Gulls and Caspian Terns.

Pelicans are drawn to a filled lake from as far

away as Papua New Guinea. During the 1989-90 flood it was estimated that 200,000 pelicans, 80% of Australia's total population, came to feed at Lake Eyre.

Lake

Eyre is a harsh environment for part time boating enthusiasts hoping to

enjoy the infrequent floods. Equally so for pilots who may run low on fuel.

YACHT

CLUB

The Lake Eyre

Yacht Club is a dedicated group of sailors who

sail on the lake's floods, including recent trips in 1997, 2000, 2001, 2004, 2007 and

2009. A number of 6 m (20 ft) trailer sailers sailed on Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre in 1975, 1976, and 1984 when the flood depth reached 3–6 m (10–20 ft). In July 2010 The

Yacht Club held its first regatta since 1976 and its first on Lake Killamperpunna, a freshwater lake on Cooper Creek. The Cooper had reached Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre for the first time since 1990.

When the lake is full, a notable phenomenon is that around midday the surface can often become very flat. The surface then reflects the sky in a way that leaves both the horizon and water surface virtually impossible to see. The commodore of the Lake Eyre

Yacht Club has

said that sailing during this time has the appearance of sailing in the sky.

Maybe they should rename the region Lake Eerie.

Bluebird

K7 on Lake Dumbleyung December 31 1964 - completing the double. Most people

having achieved this would have called it a day. Not DC, he was already

planning his next car, a rocket powered beast called Mach 1.1, or Bluebird

CN8 sometimes referred to as the CNM8.

NATIONAL

MOTOR MUSEUM, BEAULIEU - 50th ANNIVERSARY BLUEBIRD CN7

A

celebration Evening was held on Saturday 19th July 2014 at the National Motor

Museum, Beaulieu.

On 17 July 1964, despite mechanical problems and unpredictable weather, Donald Campbell and his team persevered to set a new British

Land Speed Record of 403.10mph in Bluebird CN7, at Lake Eyre in Southern Australia.

What better way to mark the 50th anniversary than to spend an evening in the company of both the iconic Bluebird CN7, and Donald Campbell’s

lovely widow,

Tonia Bern-Campbell. The evening

included a first public screening of the digitally re-mastered film ‘How Long a Mile…’, on Donald Campbell’s world record breaking year of 1964 when he took both the land and water speed records – a unique double that has never been

equaled.

The screening was followed by an exclusive dinner in the National Motor Museum and a talk by Tonia Bern-Campbell, recalling that magical time.

"Boy,

I'm glad that's over." After bitter disappointment that one cannot

begin to share in the frustration, Donald Campbell finally clinched the

land speed record. It would be another five months before he grabbed the

water speed record. His father's records were set using Rolls Royce

engines. Donald's were set with two different makes of jet engines.

DONALD

CAMPBELL'S BLUEBIRDS

K7

CN7

CNM8

The

blue bird

legend continues. The

classic lines of this electric racing

car were inspired

by Reid Railton and his designs for the Napier Lion and

Rolls Royce

engined Blue Bird LSR cars in the 1930s, the Blueplanet BE3

features instant battery recharging using the patent

Bluebird™ cartridge exchange system under license from BMS.

This LSR is also solar assisted. She is designed for speeds in excess of

350mph using clean electricity. Imagine the spectacle of this beautiful

vehicle speeding across the salt at Bonneville,

or flying past on the sand at the Daytona

or Pendine

beaches. To hire this vehicle for your venue please contact BMS

and ask for Leslie or Terry. The BE3 team need at least 6 months advance

notice of events.

SIR

MALCOLM CAMPBELL'S BLUE BIRDS

Sunbeam

Napier

Lion

Rolls

Royce

K3

K4

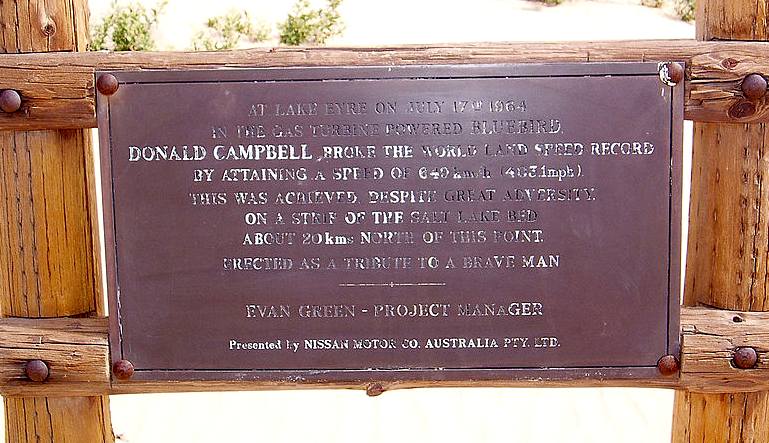

A

commemorative placque presented by the Nissan Motor Co. Australia, who

later named their under 2000cc petrol cars 'Bluebird' by arrangement

with the Norris brothers, who at the time

owned the trade mark.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Australian

Traveller see lake eyre in flood

ABC

News

2011 return to lake eyre

ABC

News 2011

just add water lake eyre

Wikipedia

Lake_Eyre

Adelaide

Now

speed-ace-donald-campbells-bluebird-landspeed-record-at-lake-eyre-turns-50-today

http://forums.kombiclub.com/index.php

Environment

Australia Kati_Thanda-Lake_Eyre_National_Park

Treasure

houses CN7 50th anniversary celebration evening with Tonia Bern-Campbell

OSQ

Alistair_Little

art

Wikipedia

Soil_mechanics

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Soil_mechanics

http://www.alistairlittle.com/

http://www.osg.uk.com/alistair_little/alistair-little-13.shtml

http://treasurehouses.blogspot.co.uk/

http://www.australiantraveller.com/sa/003-see-lake-eyre-in-flood/#

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-08-19/return-to-lake-eyre/2846552

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2011-08-19/just-add-water-lake-eyre/2846514

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lake_Eyre

|