|

Dstl

The

Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) maximises the impact of

science and technology (S&T) for the defence and security of the UK,

supplying sensitive and specialist S&T services for the Ministry of

Defence (MOD) and wider government.

Dstl

is a trading fund of the MOD, run along commercial lines. It is one of

the principal government organisations dedicated to S&T in the

defence and security field, with three main sites at Porton Down, near

Salisbury, Portsdown West, near Portsmouth, and Fort Halstead, near

Sevenoaks.

Dstl

works with a wide range of partners and suppliers in industry, in

academia and overseas. Around 60% of the Defence Science and Technology

Programme is delivered by these external partners and suppliers.

Centre

for Defence Enterprise

The

Centre for Defence Enterprise (CDE) funds research into novel,

high-risk, high-potential-benefit innovations. It offers two routes to

funding – the open competition and a series of themed competitions for

proposals that address particular defence and security challenges.

Working

with the broadest possible range of science and technology providers,

and often providing an entry point into MOD for those new to defence,

CDE aims to remove barriers for SMEs to enter the defence supply chain

providing a vital mechanism for defence to access their fresh thinking

and capabilities.

DSTL

chief executive Jonathan Lyle

Q

BRANCH - CIVIL SERVICE WORLD OCT 2013

Nestled amongst the freshly-harvested fields of southern England, near the sleepy cathedral city of Salisbury, is a 7,000-acre site where military scientists create some of the most advanced weaponry known to man.

The top-secret base of Porton Down is bathed in autumnal sunshine as your correspondent is escorted through two sets of barbed-wire security fences to reach the headquarters of the Defence, Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL).

Its chief executive, Jonathan Lyle, is waiting in the spacious open-plan lobby, while behind him teams of scientists huddle over classified paperwork, discussing plans, wielding highlighters and drinking coffee.

There’s a strange juxtaposition between the cheery informality of DSTL staff, and the deadly potential of some of their work: their relaxed demeanour belies a steely commitment to their sensitive task.

Porton Down itself has a controversial history but Lyle says the present tenant, DSTL, is a strongly-regulated, tightly-managed organisation, which uses scientific know-how to boost Britain’s defensive, medical and industrial capabilities.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF HORROR

In one form or another, military scientists have been based here since 1916, when they began producing and trying to counter the chemical weapons that wreaked havoc on all sides in the First World War. This work continued for decades, reaching its peak in the 1940s and ‘50s, when British scientists developed highly-toxic nerve agents. Work on biological weapons also moved to this site, with deadly viruses created to kill military and civilian personnel.

However, in 1956 the British government renounced the development of chemical and biological weapons, which it hasn’t deployed since World War One. “For a very long time, the UK has not had or sought to have offensive chemical or biological capabilities,” Lyle explains. “The whole emphasis of our work [in that space] is around defending or protecting our troops and the British people from the threat of chemical or biological weapons.” This includes developing protective equipment such as suits or respirators for the armed forces, and the capability to detect chemical weapons. “It also includes countermeasures: vaccines and anti-toxins that you might deploy in the event of being threatened with a chemical agent,” says Lyle; DSTL partners with the Department of Health on some of this work.

Over the past few months, DSTL’s chemical weapons experts have supported the Foreign Office and the National Security Council by identifying nerve agents used in Syria. “We have been involved in testing samples from Syria, and reporting those results to the British government,” Lyle says. “That is something that relies on world-class science. There’s a temptation to think that testing is just like sending it down to Boots the chemist, but we can only do the testing that we’ve done in relation to the alleged used of sarin in Syria… because people have had the sense to invest in the equipment, the facilities and, most of all, the people trained in the skills and methods to detect these agents.”

As UK policy has evolved, so have the organisations based at Porton Down. The site had many different occupants – generally armed forces units or elements of larger research agencies – until 2001, when most defence research was privatised. Only the really sensitive bits were kept in the public sector, named DSTL and, Lyle explains, tasked with supplying specialist chemical and biological defences and very specific components of modern weaponry.

However, “the DSTL of today is very, very different” from that of 2001, he adds, having greatly expanded its remit and support for the MoD – notably in strategic, technical and frontline operations. In 2010, Lyle’s organisation was given responsibility for managing the entire £400m

defence research budget, which it uses to “cover all of the challenges that the Ministry of Defence and the three armed services have”. It currently develops technologies for use in the air, land, sea, cyberspace, and against chemical and biological weapons.

Given the nascent technologies with which DSTL works, it must plan decades ahead for when they will be ready for deployment. “We’re thinking about the next defence review, and about what the Ministry of Defence is going to be needing in 2025 or 2030,” Lyle says. “The challenge is to be thinking about those technologies that are needed for the armed forces in the next campaign, not thinking back to the campaigns that we’ve just had.” As predictions about future warfare change, he adds, “we’ll see some reorientation in the things we choose to invest in”.

Cyber technologies are one of those priorities, he explains, while another is “autonomous systems” – devices that operate themselves without the need for a human controller – and their implications for the future of warfare. “Unmanned air vehicles, underwater vehicles, land vehicles – all these things present both opportunities and challenges,” Lyle comments.

Since 2001, DSTL has also developed a large analytics team, which supports ongoing intelligence work to understand other countries’ capabilities, and assists with military campaigns. DSTL staff are now deployed to frontline operations: a team of 20 is currently in Afghanistan, Lyle notes, “analysing what’s happening in the campaign day-to-day, then reaching back into the laboratory to invite our fantastic brains to come up with solutions and respond quickly.” As an example, he cites work to combat the use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) by the

Taliban.

TESTING TROUBLES

DSTL’s in-house research has a highly-controversial history. In the 1950s, members of the armed forces were tricked into believing that they were helping to find a cure for the common cold – only to later discover that they’d been exposed to highly-toxic nerve agents. Some died as a result. “What happened in the 1950s is a very different time, and a long time ago,” Lyle says. “That’s something that’s very much in the past.”

Does DSTL still experiment on humans? “We do use human volunteers, for example in physiological work,” he replies. “A lot of our work in this area is on the burden experienced by soldiers. So we do a lot of work on body armour, but also clothing, protection and so on. We will use human volunteers to look at physiological strength: if you put someone on an exercise machine, how can we measure the impact on the soldier of the clothing they’re wearing, and the load they’re carrying?”

Is there a risk that people could die in these experiments? Lyle’s response seems to be broader than just the experiments using human volunteers: “Everything we do is very carefully controlled – health and safety is important in a laboratory – because we deal with some quite challenging areas, whether it’s explosives or understanding the effects of chemical or biological agents. These present us with some very real challenges, so everything we do is highly regulated by the Defence Safety and Environment Authority, the Health and Safety Executive, the Environment Agency, and we strive to meet the very highest standards in doing that, as well as in medical ethics.”

Does DSTL also experiment on animals? “Yes, it’s necessary for us to use animals in the experiments that we do. We always seek to minimise the use of animals, so we will explore every other way of understanding what we need to do through modelling, through simulation, but there are certain fields where the only way of understanding what needs to be done is by using animals,” he says. “The work is regulated by the Home Office, with a dedicated inspector, and is openly declared every year to that department.”

Lyle stresses, though, that “we’re not just doing this because we fancy doing this: we do it for a very real purpose, and that is primarily around safeguarding lives. So whether it is our soldiers in Afghanistan and giving them the body armour or the other protective kit that they need, or the way in which our work here has very significantly improved trauma surgery, so that far more people are surviving incidents in Afghanistan. All of that’s come around from the experimentation that we do.”

“Our role is to provide security for the UK,” he adds. “So all that work feeds the protection that we’re seeking to give our armed forces and the British public from threats that exist in the world today… We do it in a very highly regulated way, but with a very real purpose.”

Minister

for defense Philip Dunne

Partnering up

While DSTL has a large programme of in-house research, “increasingly our role is about managing work externally,” Lyle says. “So of the £400m research programme that we manage on behalf of the MoD, some 60% of it – and an increasing proportion – is now flowing to companies, both large and small, and universities… We do that because we want to be working with the best people, and make sure we’re doing our research in the best place.”

“The challenge for us is that we’re a top secret laboratory – you’ve come through two fences to get here – and a lot of what we do is incredibly sensitive… but if we want to work with industry we have to communicate with them what we do.” Consequently, DSTL established the Centre for Defence Enterprise, which has a particular focus on finding potential suppliers among small and medium-sized businesses in areas where DSTL is seeking to expand its work. “If we have a particular challenge in countering improvised explosive devices, or needing a new sort of protection, we will describe that in unclassified terms and put out an open call to industry and academia.”

DSTL also “spins-out” its intellectual capital into the private sector. One company, P2i, uses waterproofing technology developed by DSTL to waterproof mobile phones and trainers. “That came out of our suits for chemical and biological defences – the impervious membranes we developed,” he says.

However, unlike with the Cabinet Office’s drive to encourage civil servants to leave the public sector in spin-off ‘mutuals’, DSTL is keen to hang on to its employees when it

commercializes its technologies. “Our staff continue to work for us, but clearly we help make that [product’s] transition [into the private sector]. We have a specific company called Ploughshare Innovations, which is expert in doing this.” The companies can still regularly access the scientists who developed the technologies; they just don’t get to employ them.

Austerity science

Defence is one of many areas where budgets are experiencing a tight squeeze, as the MoD’s funds were over-committed even before the coalition cuts. And DSTL is expecting to have less money in five years’ time, because investment in science and technology is set at 1.2% of the reducing departmental budget.

DSTL will therefore have to be more careful in how it invests its money, Lyle says, but he doesn’t face the pressure to shed staff that other areas do. The same is true of public sector pay restrictions. Senior officials in the MoD have spoken out against Treasury pay rules, which they believe are preventing them from recruiting and retaining the best talent – especially in procurement. Lyle, however, was “able to seek a degree of flexibility from the Treasury, which meant that the pay deal announced a couple of months ago was better than people had been expecting.”

DSTL has some protection from civil service pay rules because it is a trading fund, and Lyle has powers delegated from ministers and the MoD permanent secretary. These rules don’t apply to all changes, though, such as pension reforms or time off, and he adds that “there is a risk that, as and when the economy picks up, there’ll be more people seeking to employ scientists and engineers, and at that point it could get harder to recruit and retain the people we need.”

Elsewhere in the MoD, other models are being examined to give greater flexibility to public sector organisations – most prominently at Defence Equipment and Support (DE&S), which is moving towards a Government-owned, Contractor-operated (GoCo) model. What does Lyle think of that model, compared to his own? It’s probably not suited to DSTL in the current environment, he replies diplomatically: “I am very committed to the trading fund model: because of the work that we do, in particular in relation to international relationships, it has to be done by civil servants,” he says. “That’s something that continues to be tested, so every five years we go through a trading fund review. I’m sure that when the next one comes up in 2-3 years time, it will again ask the question, and every public sector organisation should continue to be tested about what is the right model.”

Lyle believes that DSTL’s operating model “works because it gives me the freedoms we need to operate – we manage our own capital works programme – and, because the work that we do is funded by our customers, quite unusually in government we have to persuade our customers to pay our invoices… [so this] creates a pretty strong focus on cost-consciousness and the way that time is managed.”

DSTL has been working with the people planning DE&S’s future, and has assisted in the formulation of a DE&S+ model, under which the organisation would become a trading fund rather than a Go-Co. “We’ve been able to explain to them how it works for us, and enables us to run a successful business within the public sector,” says Lyle.

An engineer’s view

Lyle’s fuzzy beard and academic air betray his roots as an engineer rather than as, say, a straight-backed sergeant major. He’s the MoD’s head of profession for science, and backs the department’s new emphasis on skills, learning and development. “For me, the future of the civil service is about having strong professions, which are externally accredited, and working together with strong leadership,” he says.

Like other civil service bodies employing a lot of specialist professionals, DSTL initially found working with training provider Civil Service Learning “quite challenging,” he says. But the organisation has now managed to create a new training model, and develop a network of scientists and engineers to share learning and skills across government. Indeed, Lyle is keen that DSTL overcome its remote location to feel like an integral part of the wider civil service. The new competency and performance management frameworks have given disparate civil service organisations a greater sense of unity, he believes.

The interview ends with Lyle proudly pointing out a testing range that stretches off into the distance. There’s a breeze blowing in my eyes, but I’m fairly sure I can see something resembling haystacks, and certainly the woods look very picturesque. This is scenery that was painted by Constable, after all.

Again, there’s that tension at the heart of DSTL: it’s a positive place in peaceful surroundings, but its technology could cause havoc and destruction, and predecessor bodies haven’t always acted responsibly. Equally, though, its current work in creating world-class defensive capabilities – and partnering with industry to do so – aims to ensure that, far beyond DSTL’s beautiful environs, Britain remains

green, pleasant, prosperous and peaceful.

DSTL

PURPOSE

Dstl´s purpose is to maximise the impact of science and technology for the defence and security of the

UK. Our role is to:

* Supply sensitive and specialist science and technology services for the Ministry of Defence (MOD) and wider

government.

* Provide and facilitate expert advice, analysis and assurance to aid decision-making and to support MOD and wider

government to be an intelligent customer.

* Lead the formulation, design and delivery of a coherent and integrated

MOD science and technology programme

using industrial, academic and government resources.

* Manage and exploit knowledge across the wider defence and security community, and understand science and

technology risks and opportunities through horizon scanning.

* Act as a trusted interface between MOD, wider government, the private sector, academia and allies to support

military co-operation, capability delivery, diplomacy and economic policy.

* Champion and develop science and technology skills across MOD, including managing the career of MOD scientists.

* They claim to start from the presumption that work should be conducted by external suppliers (industry,

universities and other research organisations) unless there is a clear reason for it to be done or led by

Dstl.

ACQUISITION

POLICY

DSLT need to understand the factors that affect acquisition decision making so that the Ministry of Defence (MOD) has a range of

options available to reduce its overall expenditure but maintain military capability.

This area of their work uses science and technology techniques and approaches to help the MOD make informed decisions, understand the long-term implications of those decisions and ultimately reduce costs in defence and deliver agile capability which is fit for the future.

MARITIME

& STRATEGIC SYSTEMS

Approximate defence research funding: £34 million (13/14).

Who does the work: Some elements are delivered directly by Dstl in-house capability with the majority of work being let directly with industry and academia via

Dstl.

Areas of work: Dstl's Maritime domain is the focus for innovation, collaboration and exploitation of science and technology (S&T) for maritime defence and security. The Maritime domain leads a coherent, pan-defence, maritime S&T programme, balancing near and long-term research and decision support, delivering impact against identified S&T priorities.

The research programme aims to deliver the following benefits:

Improved location, coverage and deterrence of submarine

threats to UK Forces/assets through de-risking innovative technologies and solutions.

De-risk unmanned underwater, surface and air systems and technologies in the Maritime environment including sensing and processing solutions

delivering mine counter-measures (MCM) in complex environments

Open architecture solutions for common core combat systems that reduce operator loading and help overcome Suitably Qualified & Experienced Persons (SQEP) and training issues.

Integrated, optimised and affordable survivability of Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary platforms.

The Maritime Domain is organised into programmes, each focusing on particular areas of work in order to achieve the strategic objectives. Our domain is closely linked with Defence Equipment and Support (DE&S) and the Technology Development Group to develop common exploitation roadmaps to pull through research from S&T into established equipment programmes as well as develop future concepts through our Technical Demonstrator Programmes (TDPs).

Dr Andrew Baxter OBE honours list

for work on armour

RESEARCH EXPLOITATION

Specific exploitation of research outcome is focused on:

Short term optimisation and survivability of current maritime systems and support to operations through Maritime Warfare Centre (MWC), Navy Command Headquarters Maritime Capability (NCHQ Mar Cap) and DE&S

ships/submarines.

Short/medium term concept, technology and system de-risking for the Successor, Vanguard Capability Sustainment (VCSP), Type 26 and

mine

counter-measures,

hydrography and patrol capability (MHPC)

programmes.

Longer term concept development for maritime underwater future capability (MUFC) and future surface platforms through NCHQ Mar Cap, Head of Nuclear Capability and Finance and Military Capability (Fin Mil Cap).

Creating the evidence base for current capability planning and decision making across the full timeframe 2013-2030+.

MARITIME PROGRAMMES

FREEDOM OF MANOEUVRE

The Freedom of Manoeuvre programme provides the S&T required to maintain freedom of manoeuvre within the maritime environment in the face of changing threats, environment and technology. Specific elements addressed by the programme include affordably re-generating anti-submarine warfare capability; enabling future delivery of underwater capability from and within the underwater battlespace; and enabling delivery of cost effective mine counter-measures and geospatial intelligence gathering capability from unmanned systems.

INTEGRATED MARITIME SURVIVABILITY

The research conducted under the Integrated Maritime Survivability programme is aimed at enhancing the performance of Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary platforms to conduct maritime security and constabulary operations, with reduced risk to the ship and crew. In the longer term the research will challenge the current approaches to conducting survivability for surface ships and submarines.

AFFORDABLE PLATFORMS

The research conducted under the Affordable Maritime Platforms programme is aimed at ensuring that future Royal Navy

ships and

submarines are more affordable to build, operate, maintain and re-role, whilst still being capable of being operated where and when they are required. This research will cover two aspects which are core to ensuring that future Royal Navy platforms are

affordable, namely:

Platform system concepts research will address the affordability of surface ships and submarines, looking at technologies to ensure that they are efficient to operate and adaptable to future requirements.

Common core combat systems research will address how we build combat systems and how we access the data from the platform's sensors to ensure that situational awareness is

optimised.

INTEGRATED CAPABILITY

This programme provides the analysis support required to deliver Evidence Based Decision Making (EBDM) within the maritime environment. The programme directly supports the MOD capability management process and thus directly contributes to the management of risk. This programme provides the link between system performance and military worth thereby supporting Capability Planning Groups (CPG) and Programme Boards (PBs) in their decision making.

HOW TO GET INVOLVED

Current opportunities are listed on the DSTL website. Alternatively, contact Dstl's Maritime domain:

maritime@dstl.gov.uk

Maritime Collaboration Enterprise 'Sense to Decide' (MarCE S2D) Community of Interest

The Maritime Collaboration Enterprise was established in November 2012 and for the first time brings together the Above Water and Under Water communities. Industry, government and academic research will address:

Tactical Information Acquisition, and Tactical Command and Battle Space Management

BAE Systems have been appointed as the Prime, supporting the Dstl Maritime domain to deliver innovative, high quality research to aid the Royal Navy in delivering the Future Navy 2020 and the Conceptual Navy 2030. For more information visit

www.baesystems.com

or email MarCES2D@baesystems.com

VESSEL EFFICIENCY - PILOTING MARINE & MARITIME INNOVATION

Through the 'Vessel efficiency: piloting marine and maritime innovation' competition for funding, the Technology Strategy Board and its partners, Dstl Maritime domain and Scottish Enterprise, are seeking proposals from businesses, whether currently inside or outside the industry. The aim of this competition is to develop solutions covering many aspects of vessel efficiency in existing and future ships, boats, submarines and their associated equipment and systems.

The investment will be made by the UK's innovation agency, the Technology Strategy

Board, through a competition for funding for fast-track and collaborative research and development projects.

ONE

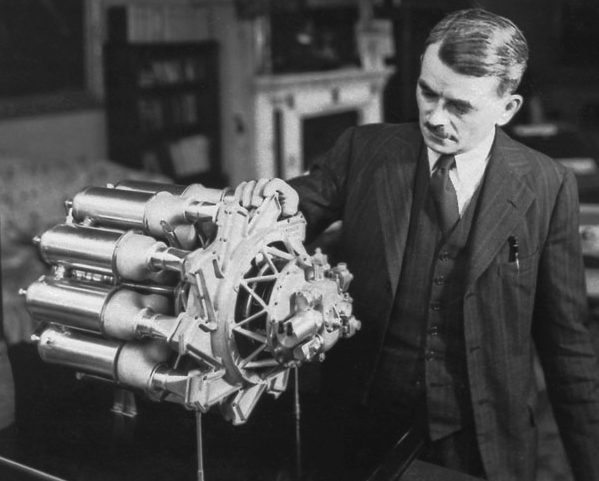

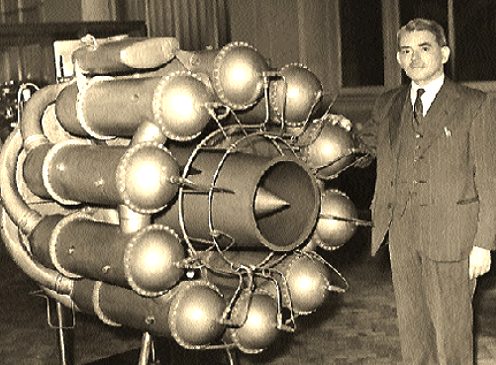

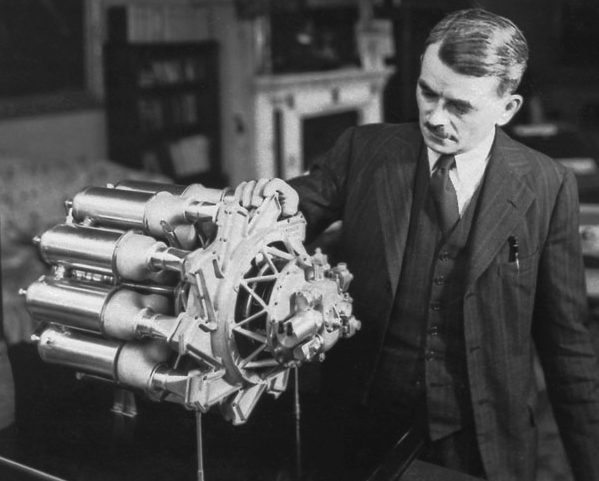

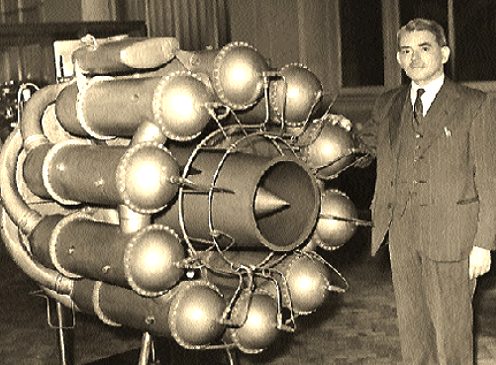

THAT GOT AWAY - Frank Whittle secured backing for his jet engine ideas with Royal Air

force Force approval in 1935. Power Jets Ltd was formed in July 1936 to

begin tests that proved inconclusive. Whittle lacked the necessary

finances until after protracted negotiations with the Air Ministry after

WWII had begun in 1940. A bit late, and uncle Adolf may have thought

twice about invasion plans if we ruled the skies with super-fast jets,

but there we are. Thank heavens we had radar. By April 1941 the engine was ready for tests.

A first flight was made on 15 May 1941. By October the United States had heard of the project and

asked for the details and an engine. A Power Jets team and the engine were flown to Washington

for General Electric to examine and begin construction. The Americans worked quickly.

Their XP-59A Airacomet was airborne in October 1942, before the British Meteor, which became operational in

1944, too late to help in the war effort. Had the MOD leapt on the idea

when it was first presented, it could have shortened the war

considerably, in addition to increasing UK revenues from the patent

that never was. The jet engine proved a winner in America where the technology was enthusiastically embraced. Whittle

was knighted in 1948 and went to work in the US shortly afterwards, becoming a research professor at the US

Naval Academy

at Annapolis. The lesson to be learned here is that innovation

germinates in response to the world around us - and we must keep up with

current trends or give ideas away for lack of support. Patent law

determines that financial backing is needed in the first Eureka year, or

becomes lost.

CENTRE

FOR DEFENCE ENTERPRISE (CDE)

The CDE is the entry point for new science and technology providers to defence, bringing together innovation and investment for the defence market, ensuring that our front-line forces have the best battle-winning technologies for the future.

The CDE funds research into novel, high-risk, high-potential-benefit innovations. CDE works with the broadest possible range of science and technology providers and often provides an entry point for those new to defence. CDE aims to remove barriers for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to enter the defence supply chain. More than two thirds of CDE contracts go to small and medium-sized enterprises and innovators within academia, providing a vital mechanism for defence to access their fresh thinking and capabilities.

CDE offers two routes to funding: the continuous defence open call and a series of themed calls for proposals, which address particular defence and security challenges, identified from within the current Defence Science and Technology Programme.

CDE was opened in May 2008 and has received more than 3,000 proposals with research contracts awarded to date worth a total of over £23.5 million. Around 15 percent of all proposals received have been funded.

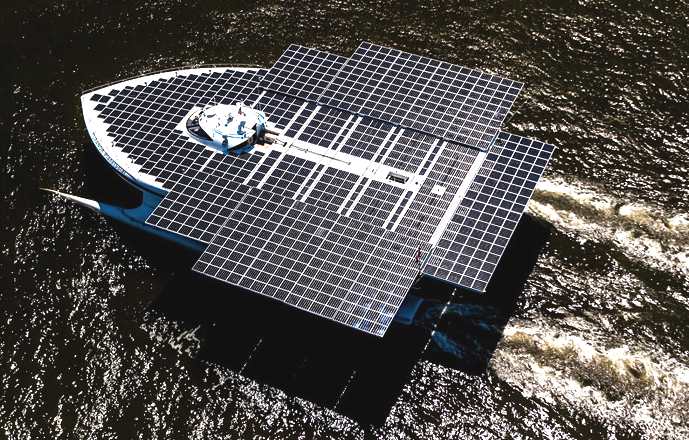

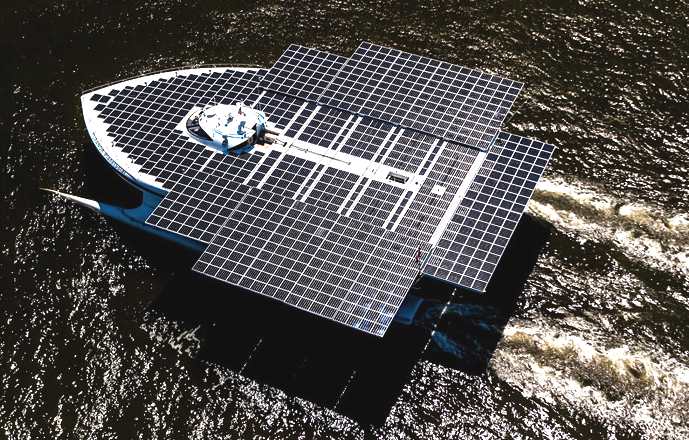

Swiss

world record breaking solar boat, idea first proposed by British

inventor in 1994/5

and repeatedly brought to the attention of the MOD - another one that

got away.

INSIGHT

inSIGHT is a defence science and technology eBulletin aimed at the supplier community. It provides suppliers with the latest on science and technology news, current Dstl

programmes, new and live contracts, case studies demonstrating work undertaken between

Dstl, industry and academia and how suppliers can get involved.

To receive Dstl's inSIGHT eBulletin, subscribe by sending an email to insight@dstl.gov.uk

including your name, your email address and your organisation's name. It would also be useful to know what areas of Dstl's work you are interested in.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

http://www.civilserviceworld.com/interview-jonathan-lyle/

http://www.science.mod.uk/Engagement/the_portal.aspx http://www.science.mod.uk/Engagement/enterprise.aspx https://www.dstl.gov.uk/centrefordefenceenterprise http://www.philipdunne.com/

https://www.dstl.gov.uk

UKHO

http://www.maritimejournal.com/news101/industry-news/ukho-appoints-new-national-hydrographer http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Kingdom_Hydrographic_Office http://www.ths.org.uk http://www.spri.cam.ac.uk/friends/committee/ http://www.thefutureofnavigation.com/ten_steps.aspx http://www.quaynote.com/ankiti/www/?code=ecdis13&f=programme

Wiki

United_Kingdom_Hydrographic_Office

https://www.dstl.gov.uk/insight

US

Department of Navy Research, development & Acquisition - http://acquisition.navy.mil/ US

Fleet Forces Command - http://www.cffc.navy.mil/

US

http://www.msc.navy.mil/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_Oceanographic_Office

PATENT

PENDING - The

key to accurate hydrographic mapping is continuous monitoring,

for which the Bluefish SNAV

platform, presently under development, is a robotic ocean workhorse. Based on a stable

SWASH

hull this design is under development in the UK, looking for international

agents and partners. The robot

ship uses no diesel fuel to monitor the oceans autonomously (COLREGS

compliant) at the relatively high

speeds of 18 knots max, and 7-10 knots cruise 24/7 and 365 days a year - only possible with the revolutionary (patent) energy harvesting system. The

hullform is ideal for automatic release and recovery of ROVs

or towed arrays, alternating between drone and fully autonomous modes.

International development partners are welcome. This vessel

pays for itself in fuel saved every ten years.

The

same platform in a modified form is suitable for adaptation to a robotic

battleship, or more in line with cost effective defence, as a fleet of

drones to persistently monitor underwater submarine and surface ship

activity - should the need arise to sink such vessels. The Wolverine

ZCC™ in its ultimate form may carry 4 Tomahawks, 30 SAMs and 4

torpedoes + an ROV or minisub.

|