|

Some

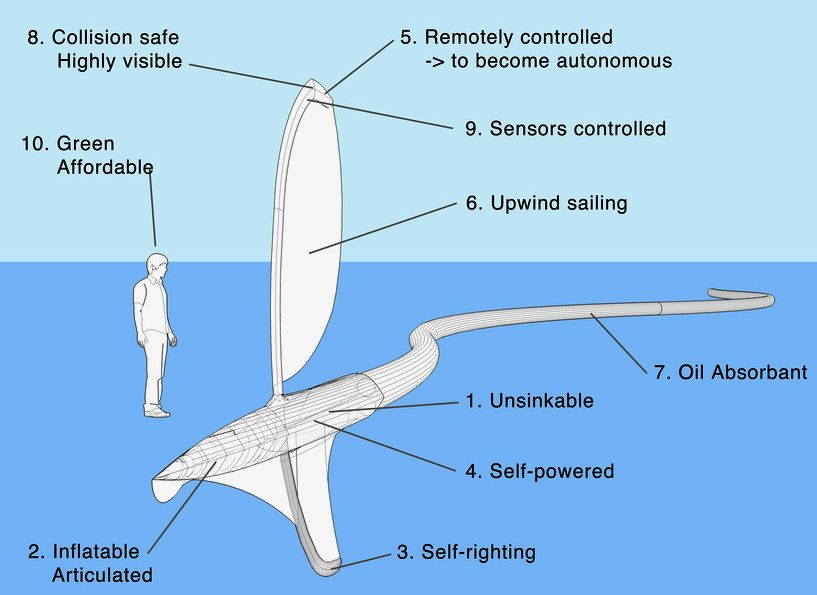

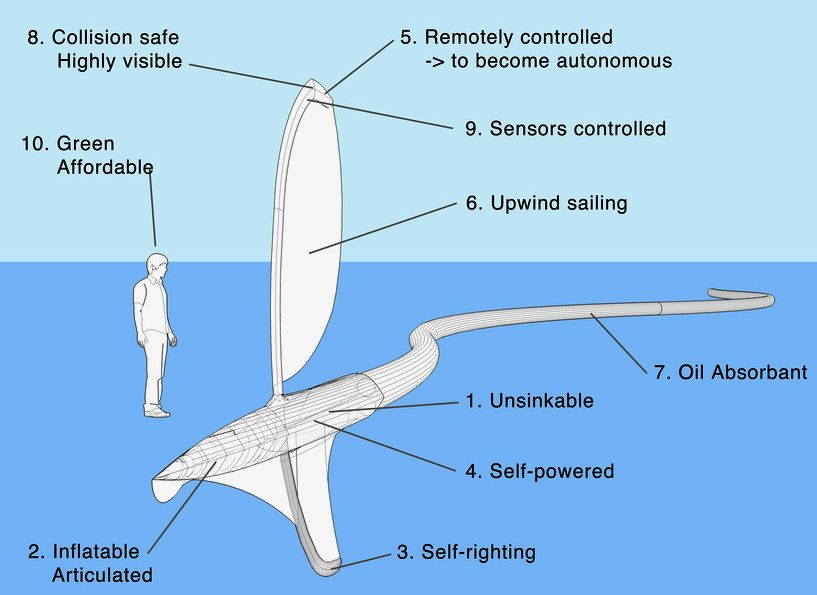

of the features of this oil cleanup concept

SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST - JULY 2014 - HONG KONG INVENTOR'S ROBOT OCEAN CLEANER

A Hong

Kong based environmentalist and inventor is developing special boats with shape-shifting hulls to help clean-up the oceans.

A Yuen Long farm an hour from the sea may not seem like the ideal location for a boat workshop, but it's where French-Japanese environmentalist and inventor Cesar Harada is based.

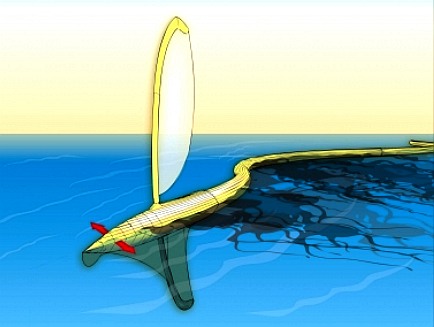

That's where he is designing and building unique robotic boats with shape-shifting hulls and the ability to clean-up oil spills. The hull changes shape to control the direction "like a fish", Harada, 30, says. It is effectively a second sail in the water, so the boat has a tighter turning circle and can even sail backwards.

"I hope to make the world's most manoeuvrable sailboat," he says. "The shape-shifting hull is a real breakthrough in technology. Nobody has done it in a dynamic way before."

Harada hopes one day a fleet of fully automated boats will patrol the oceans, performing all sorts of clean-up and data-collection tasks, such as radioactivity sensing, coral reef imaging and fish counting.

Asia could benefit greatly because, Harada says, the region has the worst pollution problems in the world. Yet the story of his invention started in the

Gulf of

Mexico, following one of the most devastating environmental disasters in recent years - the 2010

BP

oil

spill. Harada was working in construction in Kenya when the Massachusetts Institute of Technology hired him to lead a team of researchers to develop a robot that could clean-up the

oil.

He spent half his salary visiting the gulf and hiring a fisherman to take him to the oil spill. More than 700 repurposed fishing boats had been deployed to clean-up the slick, but only 3 per cent of the oil was collected.

It then dawned on him that because the robot he was developing at MIT was patented, it could only be developed by one company, which would take a long time, and it would be so expensive that it could only be used in rich countries.

This realisation made Harada quit his "dream job" to develop an alternative oil-cleaning technology: something cheap, fast and open-source, so it could be freely used, modified and distributed by anyone, as long as they shared their improvements with the community.

He moved to New Orleans to be closer to the spill, and taught local residents how to map the oil with cameras attached to balloons and kites.

Harada set up a company to develop his invention, originally based in New York before moving to Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and then San Francisco. Now, Harada says he will be based in Hong Kong for at least the next five years. He built his workshop and adjoining office in Yuen Long himself in five months on what used to be a concrete parking space covered with an iron roof after acquiring the site in June last year.

He first visited Hong Kong last year while sailing around the world on a four-month cruise for entrepreneurs and students. It is the perfect location for his ocean robotics company, he says, because the city's import-export capabilities and the availability of electronics in Shenzhen are the best in the world. Also, Hongkongers are excited about technology, setting up a business is easy, taxes are low and regulations flexible, he says.

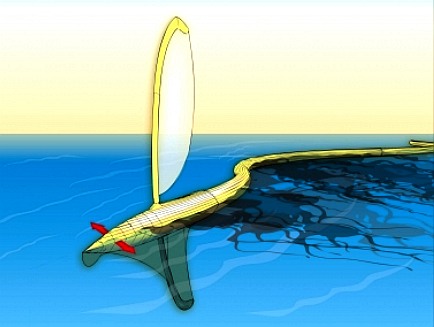

The

robotic Protei sailing boat is steered from the front and pulls a long

absorbent tail in an 'S' pattern as it sails to and fro heading into an

oil slick from downwind.

He named the boat Protei after the proteus salamander, which lives in the caves of Slovenia. "Our first boat really looked like this ugly, strange, blind salamander," Harada says with a laugh. He later discovered that Proteus is the name of a

Greek sea god - one of the sons of Poseidon, who protects sea creatures by changing form, and the name stuck.

"He is the shepherd of the sea," Harada says.

Harada built the first four prototypes in a month by hacking and reconfiguring toys in his garage, and invented the shape-shifting hull to pull long objects. A cylinder of oil-absorbent material is attached to the end of the boat that soaks up oil like a sponge. The shape-shifting hull allows the jib - or front sail - and the main sail to be at different angles to the wind, allowing the boat to sail upwind more efficiently, intercepting spilled oil that is drifting downwind.

"Sailing is an ancient technology that we are abandoning. But it's how humans colonised the entire earth, so it's a really efficient technology," Harada says.

"The shape-shifting hull is a superior way of steering a wind vessel."

The prototype is now in its 11th generation. The hull, which measures about a metre long, looks and moves like a snake's spine. Harada built 10 prototypes this month, which are sold online to individuals and institutions who want to develop the technology for their own uses.

He has collaborators in South

Korea, Norway,

Mexico and many other countries.

"The more people copy us, the better the technology becomes."

Harada, who describes himself as an environmental entrepreneur, says investors have offered to buy half of the company, but he has turned them all down. "They do not understand the environmental aspect of the business," he says. "They want to build big boats and sell them as expensively as possible."

Harada has a bigger vision for Protei. He wants to create a new market of automated boats. He hopes that one day they will replace the expensive, manned ocean-going vessels that are currently used for scientific research. He says one of these ships can cost tens of millions of dollars, and a further

US$4,000 worth of fuel is burned every day. That does not include the cost of a captain, three or four crew members, a cook and a team of researchers.

The expense of these research missions is one of the reasons we know so little about the ocean, Harada says. We have explored only 5 per cent of the ocean, even though it covers 70 per cent of the earth. "We know more about Mars than we know about the ocean."

He notes that there is no gravity in space, so we can send up huge satellites. But submarines that have tried to explore the depths of the ocean have been crushed by the pressure of the water. Ships are not free from risk, either.

Harada is quoted as saying that: "Seafaring is the most dangerous occupation on

earth."

More people die at sea than on construction sites. An automated boat would also prevent researchers from being exposed to pollution and radiation.

Harada's Japanese family live 100km from Fukushima, and he will go back there for a third time in October to measure the underwater radioactivity near the site. Although he admits to being scared, "it's the biggest release of radioactive particles in history and nobody is really talking about it".

Harada is also working with students from the Harbour School, where he teaches, to develop an optical plastic sensor. "We talk a lot about air pollution, but water pollution is also a huge problem," he says.

He says industries in countries such as India and Vietnam have developed so fast and many environmental problems in the region have not been addressed. "In Kerala

[India], all the rivers have been destroyed. The rivers in Kochi are black like ink and smell of sewage. Now it's completely impossible to swim or fish in them."

Hong Kong has not been spared, either. Harada joins beach clean-ups on Lamma Island and says even months after an oil spill and government clean-up last year, they found crabs whose lungs were full of oil. He says locals fish and swim in the water and there are mussels on the seabed that are still covered in oil.

"The problem is as big as the ocean," Harada says. But he believes if man made the problem, man can remedy it. The son of Japanese sculptor Tetsuo Harada, he grew up in

Paris and Saint Malo and studied product and interactive design in

France and at the Royal College of Art in London.

But he believes that at an advanced level, art and science become indistinguishable.

"I don't see a barrier between science and art at the top level," he says.

"It's where imagination meets facts."

Cesar

Harada at home in his workshop on a farm at Yuen Long, with one of his

robotic sailing creations to his left.

KICKSTARTER

Protei

is the plural for Proteus,

Greek sea-god and son of Poseidon.

Proteus was known for his mutability, his capability of assuming many

forms. The word protean evokes flexibility, versatility and

adaptability.

Other

versions of Protei may be designed in the future to harvest the

Great Pacific Garbage Patch, to capture heavy metal pollutants in

coastal areas, extract toxic contaminants from urban waterways, perform

oceanographic research, monitor marine life etc.

The

project attracted 331 backers, with $33,795 pledged of $27,500 goal.

See

their website: https://sites.google.com/a/opensailing.net/protei/

See

the video : http://www.youtube.com/watch

Vimeo : http://www.vimeo.com/20434995

They're

also on http://www.good.is/post/protei-an-open-source-fleet-of-oil-spill-cleaning-robot-drones/

and

Hackaday

http://hackaday.com/2011/03/12/protei-articulated-backward-sailing-robots-clean-oil-spills/

PROTEI

TEAMS

CORE

TEAM

Coordinator

: Cesar Harada (Fr, Jp), TED Senior Fellow, Open_Sailing Coordinator contact@protei.org

Project

Manager V2_ : Piem Witz (NL) piem@v2.nl.

V2_

Lab Manager : Boris Debackere (Belgium) boris@v2.nl.

Maritime

Engineer and Academic coordinator : Etienne Gernez (France, Norway), DNV

Veritas Oslo etienne@opensailing.net.

Head

Engineer : Qiuyang Zhou (China, Denmark), Mechatronics, University of

Southern Denmark.

Engineer

1 : Roberto Melendez (El Salvador, USA), Mechanical and Ocean Engineering

, MIT.

Collaborator,

Industrial Product Designer : Sebastian Müllauer (Germany).

Collaborator,

Interaction Designer & Sensors : Sebastian Neitsch (Germany).

Collaborator,

Mechanical Engineer : Henrik Rudstrom (NL, Norway).

Data

Analyst and Visualization : Sey Min (randomwalks, Korea) : sey@protei.org

; Kasia Molga (UK).

Webdesign

: Bianca Chen Costanzo (Brazil, China, USA), Apple California.

Communication

: Joris van Ballegooijen (NL), Pinar Temiz (Turkey), Hunter Daniel (USA) hunter@protei.org

Li Yu

(China), Carla Colet Castano (Spain), Ollie Palmer (UK), Yoko Kasai (JP).

A

whole fleet of robotic sailing boats

PROTEI

TEAM

Mechanical

Engineering : Joshua Updyke (USA), Logan Williams (USA), Antonio Fernandes

(Portugal)

Design

: Kisoon Olm 엄기순 (randomwalks

Korea) : kisoon@protei.org

; Sunghun (randomwalks Korea) : sunghun@protei.org

; Jieun Yoo (randomwalks Korea) : jieun@protei.org

; Amorphica Design Research Office,

Aaron

Gutierrez (Mexico, USA) amorphica@protei.org

; Julia Cerrud (Mexico, USA) julia@opensailing.net

;

Mario

Saenz (Mexico, USA) mario@amorphica.com

; Kiran Gangadharan (India), Gabriella Levine (USA).

Architecture

: Tyler Survant (USA) Yale School of Architecture.

Prototyping,

Manufacturing : Dooho Yi, Leon Spek, Jiskar Schmitz

Testing

at sea : Steven Jouwerma (NL)

SUPERVISORS

& ADVISORS

Ocean

Engineering Supervisor : Peter Keen (New Zealand, UK), University of

Southampton.

Sailing

Supervisor : Maia Anthea Marinelli (Italy, USA).

Sailing

advisor : Maia Anthea Marinelli (Italy), Gianluca Giabardo (Italy).

Electronic

supervision : Simon de Bakker, V2_ (NL).

Manufacturing

Advisor : Dominic Muren, University of Washington, The Humblefactory.

Underwater

Advisor : Dr Sarah Jane Pell, Artist, Researcher

and Commercial Diver (Australia).

Design

Supervision : Prof Jennifer Gabrys, Goldsmiths University, Design &

Environment, London.

Business

advisor : Jean Vallet, Pedagic Coordinator of Paris

WITH

SPECIAL THANKS TO

LA

Bucket Brigade : labucketbrigade.org

Suzette

Toledano : suzettebecker.com

TED.com

TEDxOilSpill

TEDxMidAtlantic

Nate

Mook

David

Troy

Earl

Scioneaux III

V2_

Director : Alex Adrianssens

Joseph

Survant

Shabnam

Anvar

Shannon

Dosemagen

Derek

Nakano Jones

Mauro

Martino

Cesar

and his students after another session experimenting with robot boats

ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BERING - CARIBBEAN

- CORAL - EAST

CHINA - ENGLISH CH - GULF

MEXICO

INDIAN

- MEDITERRANEAN - NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC - PERSIAN

GULF - SEA JAPAN - STH

CHINA

PLASTIC

OCEANS

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Kickstarter

Cesar Harada Protei open hardware oil spill cleaning sailing robot Google

open sailing Protei SCMP

inventor designs boats shape shifting hulls help clean oceans Wikipedia

Marine_debris National

Geographic 2014 July ocean-plastic-debris-trash-pacific-garbage-patch Plastic

Soup News Blogspot 2014_July World

Wildlife Fund Pollution Salon

2014/09/14

we_cant_strain_the_entire_ocean_the_horrifying_truth_about_where_our_plastic_ends_up Un

package me.whats wrong with plastic Neuro

research project 2013 death-by-plastic https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/cesarminoru/protei-open-hardware-oil-spill-cleaning-sailing-ro

https://sites.google.com/a/opensailing.net/protei http://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/technology/article/1561227/inventor-designs-boats-shape-shifting-hulls-help-clean-oceans http://unpackageme.com/whats-wrong-with-plastic/ http://neuroresearchproject.com/2013/02/21/death-by-plastic/ http://www.worldwildlife.org/threats/pollution http://plasticsoupnews.blogspot.co.uk/2014_07_01_archive.html http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marine_debris http://www.plasticoceans.net/the-foundation/ http://www.greatrecovery.org.uk/plastic-its-a-lovehate-thing/

SEAVAX

PATENT

PENDING - A non-polluting vessel such as the SeaVax concept above

could be an ideal base engine when it comes to filtering garbage from the world's ocean

gyres. The SeaVax is a robotic

ocean workhorse that is based on a stable

SWASH

hull. This design uses no diesel fuel to cruise the oceans autonomously (COLREGS

compliant) at between 7-10 knots 24/7 and 365 days a year as required. With such awesome power generating

capability, a ZCC can be adapted to extract plastic waste from ocean garbage

patches. Several of these cleaners operating as Atlantic, Indian and Pacific

ocean fleets could make such

conservation measures cost effective, and even potentially attractive to

governments around the world - for the health of the world. Recovered

plastic could be processed to produce oil, energy or recycled products.

Better than letting fish and seabirds eat the waste and kill themselves, and

who knows how that may affect us, where seafood is an essential resource for

mankind.

|