|

What

is brown and stinks? G7 climate policies - the proof of which is the

sargassum state of emergency

THE

SARGASSUM SEASON 2022

The 2022 sargassum season began at the beginning of spring due to a rise in sea temperature, which accelerates the reproduction of the seaweed. As the days get warmer, the presence of sargassum is expected to increase. Beaches with the highest seaweed count include Playa del Carmen, Tulum, and some points between Cancun and Puerto Morelos.

The Mexican government and hotels in the Yucatan Peninsula have stepped up their efforts to tackle it, however, the majority of low-budget hotels and hostels do not have the means to

clean their beaches on a daily basis.

If you’re keen to avoid sargassum on your Mexico visit, make sure to stay in a hotel that has staff constantly monitoring the ever-changing situation and has the means to tackle the issue.

Pristine

white sand beach

LATEST NEWS ON SARGASSUM SEAWEED

Rear Admiral César Gustavo Ramírez Torralba, Coordinator of the Sargassum Attention Strategy and Secretary of the Navy, has reported that in the coming days, a barrier will be stationed in front of Puerto Morelos.

In the first week of April the sea barrier will be installed in Playa del Carmen, and again in Tulum in the second week of April. In Mahahual, progress stands at 500 meters of installation, with completion expected this week. Rear Admiral López added that sargassum collection vessels will also be used at sea to catch sargassum before it reaches the coast.

The Governor of the state of Quintana

Roo, home to the Riviera Maya, has commented “We know this is a natural phenomenon that generates adverse conditions, but we will be working with the Secretary of the Navy, the municipalities, hotels and the private initiative with our best efforts to keep the beaches clean so that they continue to be a great tourist attraction,”.

According to Rear Admiral César Gustavo Ramírez Torralba, Coordinator of the Sargassum Attention Strategy and Secretary of the Navy,

Cancun, Riviera Maya region forecasting less Sargassum

Seaweed in 2021.

Torralba announced that 9,320 meters (30,578 feet) of containment barriers were installed just off the beaches of Puerto Morelos, Solidaridad, Tulum, and Mahahual and Xcalak and 11 vessels will be dedicated to the purpose in shallow waters off the coasts of Benito Juárez (Cancún), Puerto Morelos, Solidaridad (Playa del Carmen), Tulum and Othón P. Blanco (Mahahual, Xcalak).

Additionally, this year (2021), an ocean vessel will be incorporated that will allow collection from the sea in various areas, depending on the largest sargassum concentrations.

FT

FINANCIAL TIMES - 2019 - MEXICAN TOURIST INDUSTRY COUNTS COST AS SEAWEED COVERS BEACH

Since 2011, sargassum has been strangling some of Mexico’s best-loved beaches in increasingly large amounts, causing not just a stink and an eyesore but damaging coral reefs and marine ecosystems.

Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula is particularly exposed, but the seaweed has been clogging up beaches across the Caribbean and Florida in a man-made catastrophe of rising proportions. But the arrival of an island of seaweed about the size of Jamaica is a worrying escalation.

“This is the biggest environmental disaster for Mexico — these are some of the most biodiverse areas in the world,” said Esteban Amaro, a hydrobiologist monitoring the seaweed.

Stephen Leatherman, a beach expert at Florida International University, agreed. “There’s been nothing like this in the past, to my knowledge. This much sargassum is a disaster,” he said.

“If we don’t do something about it soon, the damage will become irreversible . . . in years, not decades,” added Brigitta van Tussenbroek of the seagrass laboratory at Unam university in Mexico City.

Sargassum has been observed in the Atlantic since the time of the conquistadores, but massive deforestation in the Amazon to clear land for farming, and intensive use of fertilisers, have pumped nitrogen into the oceans, boosting algae growth. Helped by warmer ocean temperatures, scientists say, the amount of seaweed has exploded.

At sea, sargassum is alive and provides a habitat for turtles and fish. But once it comes ashore and dies, it produces toxic gases and leaches acid and heavy metals back into the sea, altering the water’s pH and depriving the oceans of oxygen. That has led to the spread of white syndrome, an aggressive coral disease, Mr Amaro said.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Mexico’s president, has mobilised the Mexican marine corps to combat the algae with measures such as seaweed-catching ships and barriers. He is budgeting $2.7m to tackle the problem.

But this is less than a tenth of what hoteliers on the affected coast expect to pay for cleaning beaches this year. The president — who has already angered the $23bn tourism industry by scrapping the tourist board in an austerity drive — has also incensed local businesses by saying the seaweed’s impact on the region — which accounts for half of tourism’s 8.7 per cent contribution to GDP — was “not very serious”.

As the summer holiday season starts, public opinion is also at odds with Mr López Obrador: half of respondents in a survey by pollster Mitofsky saw sargassum as a serious, national problem. Tourism is the third biggest revenue earner behind car manufacturing and remittances.

Hoteliers fear that, if Mexico fails to combat the seaweed, tourists will choose resorts elsewhere in the Caribbean, such as the Dominican Republic, which has successfully combated the algae with sea barriers.

At Akumal bay, near Tulum, tourists enjoy cocktails overlooking a clean beach and clear waters — but achieving that is an endless battle that can cost each hotel 1m pesos ($52,000) a month, said David Ortiz Mena, president of the Tulum Hotel Association.

“Hotels are investing unsustainable sums in fighting sargassum,” he added. “Some nights we remove 400 cubic metres . . . a lot of people are overwhelmed.”

Along Tulum’s beachfront, some hoteliers are considering closing because the beach weddings — a mainstay of their trade — have dried up.

Francesca Pesaresi, owner of the María del Mar hotel, which has nine luxury suites, said the situation was “pretty disastrous”. Advance bookings had fallen by 80 per cent and overall occupancy was a quarter down on last year.

“We pay 3 per cent tourist tax and tourists pay a departure tax — if just 1 per cent of this were used to fight sargassum, it would be a huge help,” she said. “Sargassum is going to be here forever. It’s killing our seas and coral.”

Hoteliers on the Riviera Maya, which stretches 120km from Puerto Morelos to Punta Allen, have lost an estimated $12m this year from cancellations related to sargassum, according to industry data. But tourists already in Mexico were putting on a brave face.

“We knew about it, we read about it, but it’s very different to actually be here seeing it, smelling it,” said Ben Brenson, an aircraft ground worker from Chicago who acknowledged that, had he not been attending a wedding, “we probably would have chosen a different destination”.

“I guess this is what we’re doing to nature,” he said. “It’s our own doing and people don’t realise it.”

https://www.ft.com/content/80e09a68-9b88-11e9-9c06-a4640c9feebb

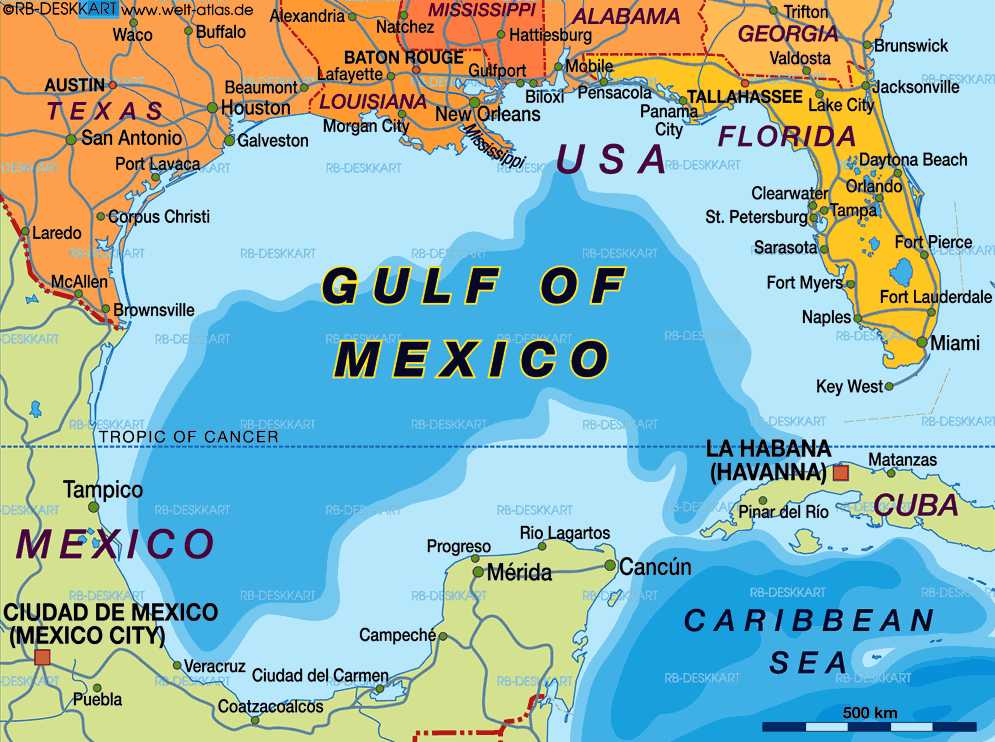

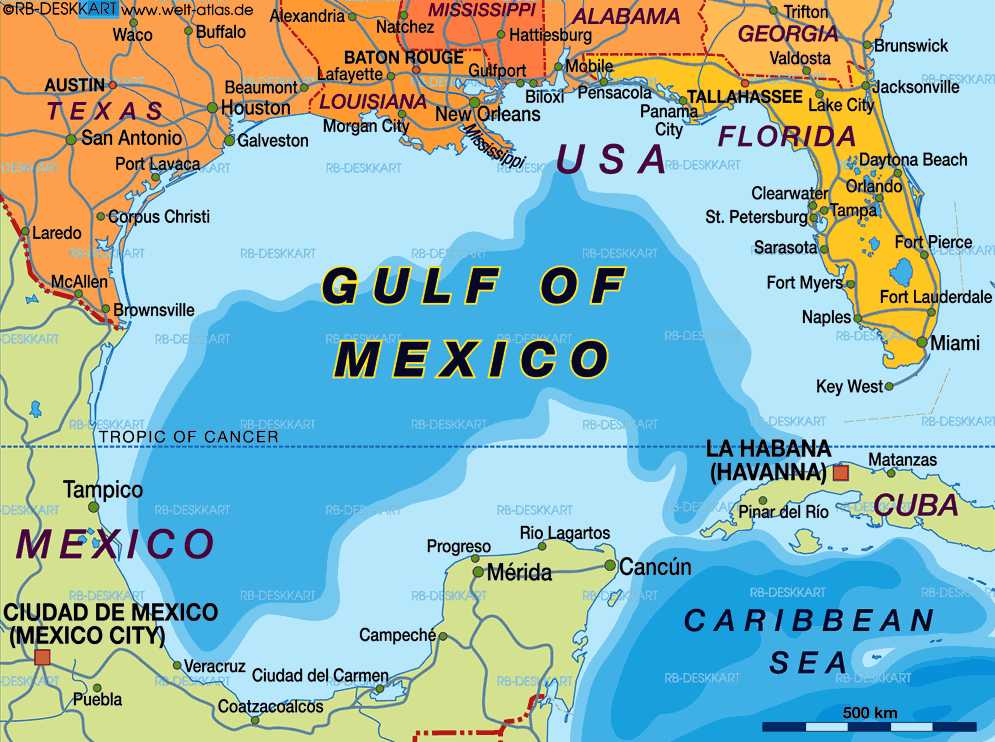

Map

of the Gulf of Mexico

ECOWATCH MAY 13 2016

The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement has tightened regulations for offshore operators ever since the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion that claimed the lives of 11 men and caused the largest man-made oil spill in history after dumping 3 million barrels of oil into the Gulf.

Still, environmental advocates have criticized Big Oil’s insistence that offshore drilling can be done safely and have urged for the practice to stop.

“The last thing the Gulf of Mexico needs is another oil spill,” Vicky Wyatt, a Greenpeace campaigner, told EcoWatch. “The oil and gas industry’s business-as-usual mentality devastates communities, the environment, and our climate. Make no mistake, the more fossil fuel infrastructure we have, the more spills and leaks we’ll see. This terrible situation must come to an end. President Obama can put these leaks, spills, and climate disasters behind us by stopping new leases in the Gulf and Arctic. It’s past time to keep it in the ground for good.”

The Louisiana Bucket Brigade noted in a press release this morning that the federal National Response Center clocks “thousands” of oil industry accidents in the Gulf of Mexico every year.

“What we usually see in oil industry accidents like this is a gross understatement of the amount release and an immediate assurance that everything is under control, even if it’s not,” Anne Rolfes, Louisiana Bucket Brigade founding director, said. “This spill shows why there is a new and vibrant movement in the Gulf of Mexico for no new drilling.”

The Louisiana Bucket Brigade, which aims to end petrochemical pollution in the Pelican State and a transition to renewable energy, said that on the same day as Shell’s accident, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) held a hearing focused on the environmental impact of oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico. During the hearing, Gulf residents brought in tar balls found just last month at Elmer’s Island in Grand Isle, Louisiana as evidence that BOEM’s environmental impact assessment is inadequate, the group said.

Gulf residents opposed to drilling are calling on President Obama not to open additional leases in the next Five Year Plan for the Gulf of Mexico.

“This latest offshore oil disaster once again demonstrates the inherent dangers of fossil fuels, and the irresponsibility of allowing new oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico even as these spills continue to happen,” Marc Yaggi, executive director of Waterkeeper Alliance, said. “We have a decade-long, ongoing oil spill that the government won’t force Taylor Energy to fix and the Gulf is struggling from the impacts of Deepwater Horizon. The Gulf must no longer be treated as a sacrificial zone. It is time that the federal government recognized that for the health of our ocean, coasts and climate, there must be no further offshore oil leasing.”

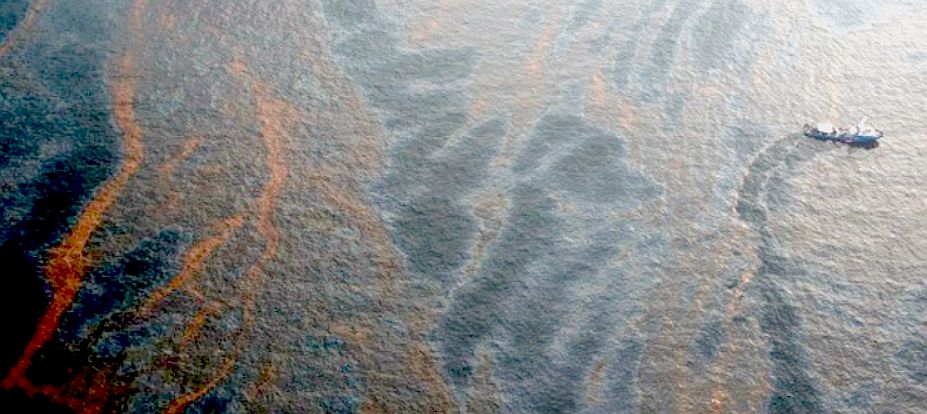

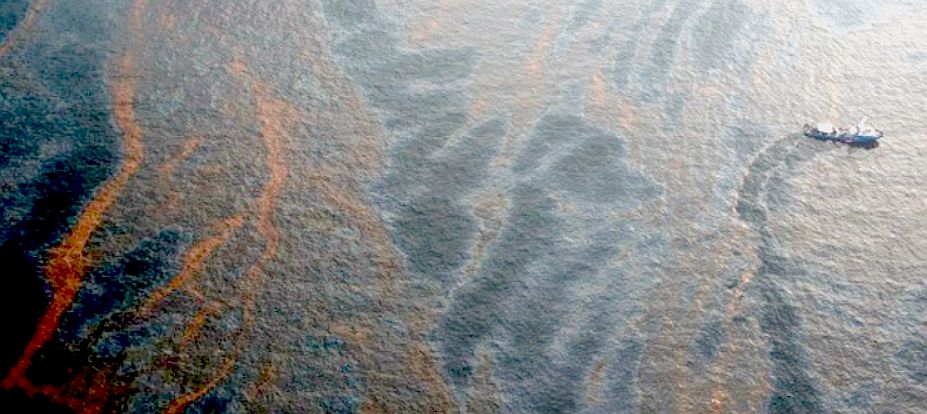

NBC

NEWS MAY 12 2016 - Almost 90,000 gallons of crude oil gushed from a Shell oil facility into the Gulf of Mexico off the Louisiana coast on Thursday, leaving a

13 x 2 mile sheen of oil on the waves according to federal authorities.

The Coast Guard said that the spill had been contained and that two companies were being contracted to begin cleanup operations. The Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement, which is part of the U.S. Interior Department, said Shell Offshore Inc. reported that production from all wells that flow to its Brutus platform, about 90 miles south of Timbalier Island, Louisiana, had been shut off.

No injuries or evacuations were reported, the safety bureau said.

Shell said Thursday night that a company helicopter spotted the sheen near its Glider subsea system at the Brutus platform. No drilling occurs at the site, which is an underwater pipe system that connects to a central

hub. Shell is quoted as saying: "No release is acceptable, and safety remains our priority as we respond to this

incident." By Alex Johnson

TELEGRAPH

12 APRIL 2012 - Shares in Royal Dutch Shell had dropped 4pc in London in early trading after the company said it had send a spill response vessel and asked for aerial surveillance to investigate the oil sheen "out of prudent caution", but by mid-afternoon they were down just 0.9pc. They closed down just 0.5pc at £21.74.

Traders said the knee-jerk response on investors reflected concerns that any possible Gulf of Mexco spill might be compared to that which resulted from BP's Deepwater Horizon rig disaster in 2010 - the worst offshore oil spill in US history.

Shell said in an initial statement that the source of the one-mile by 10-mile sheen is unknown and there was no current indication that it originates from wells in either its Mars or Ursa projects. It said its "priority is to respond proactively, safely, and in close coordination with regulatory agencies".

However, in a statement on Thursday afternoon, Shell it had it inspected its operations in the area and their was "no sign of leaks" or "well control issues" associated with it drilling operations.

Bill Tanner, a spokesman, said in an interview with Bloomberg: "This was an orphan sheen. We continue to look to identify the source of the sheen. We have a high degree of confidence that the sheen did not originate from Shell operations.”

16

FEBRUARY 2016

Judge Carl J. Barbier of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana granted

summary judgment in favor of the various commercial oil spill response companies involved in the federal government’s response to the Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

DOLPHIN

DEATHS - Study finds link with unusual frequency of deaths.

ECOWATCH MAY 21 2015

A newly released study funded by the Deepwater Horizon National Resource Damage Assessment, which includes the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), National

Fish and Wildlife Foundation, BP (the oil company responsible for the spill and others) details the disastrous impact for the spill on the health and mortality of dolphins in the Gulf.

The study, with the very scientific name of Adrenal Gland and Lung Lesions in Gulf of Mexico Common Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) Found Dead following the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, analyzes what it calls “an unusual mortality event (UME)” among dolphins off the coast of Louisiana, Alabama and Mississippi between February 2010 and 2014. More than 1,300 dolphins are estimated to have died.

“The Deepwater Horizon oil spill was proposed as a contributing cause of adrenal disease, lung disease and poor health in live dolphins examined during 2011 in Barataria Bay, Louisiana,” said the study. It also analyzed dead dolphin carcasses stranded in the three states between June 2010 and December 2012 and compared the analyses to dead, stranded dolphins found outside the area or prior to the oil spill to come to the conclusion that the die-off was unprecedented and the result of an adrenal gland condition never previously seen in dolphins in the region that made them susceptible to pneumonia.

“The rare, life-threatening and chronic adrenal gland and lung diseases identified in stranded UME dolphins are consistent with exposure to petroleum compounds as seen in other mammals,” the study concluded. “Exposure of dolphins to elevated petroleum compounds present in coastal Gulf of Mexico waters during and after the Deepwater Horizon

oil spill is proposed as a cause of adrenal and lung disease and as a contributor to increased dolphin deaths.”

“Animals with adrenal insufficiency are less able to cope with additional stressors in their everyday lives, and when those stressors occur, they are more likely to die,” said Dr. Stephanie Venn-Watson, the study’s lead author and veterinary epidemiologist at San Diego’s National Marine Mammal Foundation.

ABC

NEWS, APRIL 1 2015 - OIL RIG EXPLOSION IN GULF OF MEXICO KILLS 4

The

Gulf of Mexico is turning into an accident blackspot with explosions in

2014 and 2015. An explosion and ensuing

fire on an

oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico

on the 1st of April 2015 left four dead and injured 45 others, according to the

Mexican state-run Pemex oil company. Pemex said that 300 workers had been evacuated after the fire broke out on their Abkatun Permanente platform.

Pemex

is quoted as saying in a statement that no spill occurred: "The fire that broke today at the Abkatun processing platform in Campeche did not cause an oil spill in the sea. Authorities only registered a runoff, which is being contained by specialised

vessels."

According

to Pemex, among those killed was a contractor for the Mexican oil services company, Cotemar. Employees who escaped told the Associated Press

that some people were forced to jump into the shallow waters to escape the blaze.

Original story By GILLIAN MOHNEY

ABC

NEWS, NOVEMBER 20 2014 - 1 KILLED, 3 INJURED IN OIL RIG EXPLOSION

One person was killed and three others were injured in an explosion on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico

on the 20th of November 2014, according to the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE).

The three injured workers were undergoing treatment in a medical facility on the rig, said the

BSEE at the time.

The explosion happened about 4 p.m. on board an oil rig roughly 12 miles off the coast of New Orleans.

The oil rig is owned by Houston-based Fieldwood Energy, which reported the explosion. The rig wasn't in production at the time of the explosion, said the

BSEE.

The damage was limited to the explosion area and no pollution was reported.

It was unclear what caused the explosion. The BSEE was investigating.

THE

GREAT INVISIBLE NEW YORK TIMES 28 OCT 2014

“The

Great Invisible,” Margaret

Brown’s quietly infuriating documentary

film about the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill, includes depressing

information that many would probably be happier not knowing.

Since

the

catastrophe, which began with an oil

rig explosion that killed 11 workers and led to a discharge of millions of

barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, the company that operated the rig,

BP, has cleaned up less than one-third of the spill, according to the

film. More than four years later, Congress has yet to pass any safety

legislation for the petroleum industry. Of the multibillion-dollar profits

made by BP over a recent three-year period, the film says, less than a

tenth of 1 percent was spent on safety. After a brief moratorium on offshore

drilling, the ban was lifted, and there are now more rigs in the Gulf

of Mexico than before the disaster.

The

film, for which BP executives declined to be interviewed, is not a

thunderous, finger-pointing exposé of corporate greed and mismanagement.

Nor is it a dry, fact-filled history of the disaster or an analysis of the

technology of oil drilling. The 92-minute movie also leaves it for others

to explore the spill’s ecological and environmental impact. There are a

few obligatory images of sea birds coated with oil and aerial shots of oil

slicks destined for the Gulf Coast.

The

principal focus is on the everyday people whose lives were disrupted. A

similar emphasis on human beings informed Ms. Brown’s acclaimed 2008

documentary, “The

Order of Myths,” an exploration of Mardi Gras culture in Mobile,

Ala.

The

new film’s ground-level

perspective includes interviews with several people who received

minimal compensation from the $20 billion trust fund established to settle

claims from the spill. The mistrustful attitude of these tough,

independent workers near the bottom of the economic ladder toward those

near the top is the underlying theme here. The glaring contrast between

grim oyster shuckers and idled fishermen and Houston executives crowing

about the fundamental importance of oil to the economy suggests a tragic

disconnect between society’s haves and have-nots.

Caught

in the middle are people like Douglas Harold Brown, the Deepwater

Horizon’s chief mechanic, who was aboard the rig when the explosion took

place. Mr. Brown delivers a moment-by-moment account of the disaster,

while the screen shows the inferno of billowing smoke and flames. Mr.

Brown details how he and the workers on the rig were pressured to

eliminate jobs to save money. “Everybody knew” the dangers, he

says. “It makes me feel guilty, because I played along. I knew what I

was doing was wrong.” He links that failure to a macho culture in

the oil business that glorifies risk-taking.

One

of the most revealing scenes shows the chief executives of top oil

companies answering questions before Congress and sounding like guilty,

overgrown boys facing a grade school principal after being caught

cheating. In another scene, a smug industry honcho gloatingly surmises

that the American thirst for oil is so enormous that if the supply were

cut off, the economy would collapse within hours.

The

film’s portrayal of the trust fund, administered by Kenneth R. Feinberg,

suggests that money was mismanaged and cut off prematurely. Many who were

promised restitution received one or two small checks, then nothing. Mr.

Feinberg, who comes across as highhanded and grandiose, acknowledges that

he “overpromised” prompt delivery of relief.

Amid

the cynicism, evasion and denial, a local hero stands out. Roosevelt

Harris, a volunteer at a food pantry in Bayou La Batre, billed as

Alabama’s seafood capital, advises the embittered and despairing workers

who lost their jobs and homes to file claims. Such is their lack of faith

in the system that they would rather not bother.

MOVIE

COMMENTS

Bunk McNulty

- "...advises the embittered and despairing workers who lost their jobs and homes to file claims. Such is their lack of faith in the system...

Jose

- You gotta think about the executives at BP, how they can sleep at night and if they can, what kind of people they have become. And no doubt...

Marc Schenker

- Perhaps 60 Minutes and Scott Pelley could do a follow up to the utterly shameless PR segment they did featuring the oh so sad and suffering...

|