|

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE LAW OF THE SEA

|

|||||||||

|

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is the international agreement that resulted from the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III), which took place between 1973 and 1982. The convention was opened for signature on 10 December 1982 and entered into force on 16 November 1994 upon deposition of the 60th instrument of ratification. The convention has been ratified by 167 parties, which includes 166 states (163 United Nations member states plus the UN Observer state Palestine, as well as the Cook Islands and Niue) and the European Union. An additional 14 UN member states have signed, but not ratified the convention. Subsequently, the "Agreement relating to the implementation of Part XI of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea" was signed in 1994, amending the original Convention. The agreement has been ratified by 147 parties (all of which are parties to the Convention), which includes 146 states (143 United Nations member states plus the UN Observer state Palestine, as well as the Cook Islands and Niue) and the European Union. An additional 3 UN member states have signed, but not ratified the Agreement.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MARINE WASTE POLICY

1 November 1967 - Malta’s Ambassador to the UN, Arvid Pardo, asked the nations of the world to recognize a looming conflict that could devastate the oceans. In a speech to the General Assembly, he called for “an effective international regime over the seabed and the ocean floor beyond a clearly defined national jurisdiction.”

The speech set in motion a process that spanned 15 years and saw: the creation of the UN Seabed Committee; the signing of a treaty banning the emplacement of nuclear weapons on the seabed (currently ignored by the military); the adoption of a declaration by the General Assembly that all resources of the seabed beyond the limits of national jurisdiction are the “common heritage of mankind”; and the convening of the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment.

These were some of the factors that led to the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea, during which the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted.

UNCLOS: Opened for signature on 10 December 1982, in Montego Bay, Jamaica, UNCLOS entered into force on 16 November 1994. It sets forth the rights and obligations of states regarding the use of the oceans, their resources and the protection of the marine and coastal environment. It is commonly regarded as establishing the legal framework for all activities in the oceans.

MARPOL: The International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships in 1972. This Convention is known as MARPOL and has been amended by two Protocols and several amendments. The MARPOL Convention addresses pollution from ships by garbage among other pollutants. A revised Annex V generally prohibits the discharge, from ships, of all garbage into the sea.

LONDON CONVENTION: The Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter 197, also known as the “London Convention,” has been in force since 1975. It is one of the first global conventions to protect the marine environment from human activities, and seeks to promote the effective control of all sources of marine pollution and to take steps to prevent pollution of the sea by dumping of wastes and other matter. The “London Protocol” was agreed to in 1996 and entered into force in 2006. Under the Protocol, all dumping is prohibited, except for possibly acceptable wastes on a “reverse list.”

GPA: The Global Programme of Action for the Protection of the Marine Environment from Land-based Activities was created in 1995. This agreement seeks to protect and preserve the marine environment from the impacts of land-based activities, and deals with all land-based impacts on the marine environment, including those resulting from sewage and litter.

REGIONAL SEAS: In addition, 18 Regional Seas Programs, Conventions and Protocols, 13 of which administered by UNEP, also contain provisions relevant to the prevention of marine pollution, including marine litter.

PLASTIC WASTE WORLD MAP - This world map derived from a National Geographic source, shows that the North Pacific Gyre is by far the largest - and divided into three regions, the western, sub-tropical-convergence zone and eastern garbage patches. We estimate these patches collectively to be around 80,000 tons in mass.

UNCLOS

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), also called the Law of the Sea Convention or the Law of the Sea treaty, is the international agreement that resulted from the third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III), which took place between 1973 and 1982. The Law of the Sea Convention defines the rights and responsibilities of nations with respect to their use of the world's oceans, establishing guidelines for businesses, the environment, and the management of marine natural resources. The Convention, concluded in 1982, replaced four 1958 treaties. UNCLOS came into force in 1994, a year after Guyana became the 60th nation to sign the treaty. As of January 2015, 166 countries and the European Union have joined in the Convention. However, it is uncertain as to what extent the Convention codifies customary international law.

NATIONAL

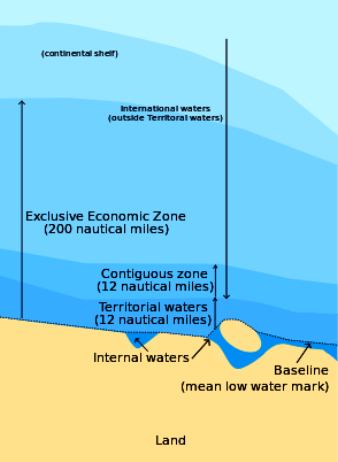

TERRITORIAL LIMITS - In the early 20th century, some nations expressed

their desire to extend national claims: to include mineral resources, to

protect fish stocks, and to provide the means to enforce pollution

controls. (The League of Nations called a 1930 conference at The Hague,

but no agreements resulted.) Using the customary international law

principle of a nation's right to protect its natural resources, President

Truman in 1945 extended United States control to all the natural resources

of its continental shelf. Other nations were quick to follow suit. Between

1946 and 1950, Chile, Peru, and Ecuador extended their rights to a

distance of 200 nautical miles (370 km) to cover their Humboldt Current

fishing grounds. Other nations extended their territorial seas to 12

nautical miles (22 km).

UNCLOS III

The United States Senate is a legislative chamber in the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the U.S. House of Representatives makes up the U.S. Congress.

First convened in 1789, the composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each state is represented by two senators, regardless of population, who serve staggered six-year terms. The Senate chamber is located in the north wing of the Capitol, in Washington, D.C. The House of Representatives convenes in the south wing of the same building.

USA - OUTLAWS OF THE SEA

UNCLOS was first negotiated 30 years ago when U.S. President Ronald Reagan objected to it because, he argued, it would jeopardize U.S. national and business interests, most notably with respect to seabed mining. A major renegotiation in 1994 addressed his concerns, and the United States signed. Now, the U.S. Navy and business community are among UNCLOS' strongest supporters. So, too, was the George W. Bush administration, which tried to get the treaty ratified in 2007 but failed due to Republican opposition in the Senate.

Today's opponents, including Ayotte, DeMint, and Portman, focus on two issues. First, they argue, the treaty is an unacceptable encroachment on U.S. sovereignty; it empowers an international organization - the International Seabed Authority - to regulate commercial activity and distribute revenue from that activity. Yet sovereignty is not a problem: During the 1994 renegotiation, the United States ensured that it would have a veto over how the ISA distributes funds if it ever ratified the treaty. As written, UNCLOS would actually increase the United States' economic and resource jurisdiction. In fact, Ayotte, DeMint, and Portman's worst fears are more likely to come to pass if the United States does not ratify the treaty. If the country abdicates its leadership role in the ISA, others will be able to shape it to their own liking and to the United States' disadvantage.

The opponents' second claim is that the treaty would prevent the U.S. Navy from undertaking unilateral action, such as collecting intelligence in the Asia-Pacific region, because permission to do so is not explicitly granted in the text. According to Admiral Samuel Locklear, commander of U.S. Pacific Command, however, "The convention in no way restricts our ability or legal right to conduct military activities in the maritime domain." On the contrary, as U.S. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta put it, U.S. accession to the convention "secures our freedom of navigation and overflight rights as bedrock treaty law." Even so, critics point out, the ultimate indispensability of U.S. naval power means that the country can receive the benefits of the convention without being bound by it. Since the world seems to have functioned perfectly well in this halfway house for some time, it would make no sense to codify the convention now. It would be comforting if all that were true. It isn't.

UNCLOS has become an important barometer of U.S. power in the Pacific Ocean. At stake is the country's capacity to uphold, preserve, and strengthen a rules-based order in Asia as China rises. In July 2010, at the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in Hanoi, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton stated that the United States believes that all maritime territorial disputes in the South China Sea must be resolved multilaterally and in accordance with international law. It is a policy that she repeated at the deadlocked 2012 ARF in Cambodia. For its part, China objected to the "multilateralization" of maritime disputes then and continues to do so now. Beijing believes that it is more likely to make gains if it strikes individual bargains with weaker powers, including Manila and Hanoi. The other capitals realize this, which is why they welcomed Clinton's commitment to multilateralism.

A strong multilateral structure in Asia is a prerequisite to balancing Chinese assertiveness. The United States should not take sides in other countries' disputes, but it can and must insist upon a strong regional framework to ensure that a rising China does not destabilize the status quo. On this issue, the 34 senators who oppose the treaty are taking Beijing's side. They are speaking up for the bilateralism and unilateralism that will harm the U.S.-led regional order in the Asia-Pacific. No doubt, news of Ayotte and Portman's recent declarations was greeted warmly in Beijing. U.S. allies and strategic partners in South East Asia, meanwhile, will be even more doubtful of Washington's capacity to maintain its leadership role. It is strategic multilateralism in the Atlantic that helped the United States to win the twentieth century. Without concordant multilateralism in the Asia-Pacific, it will not fare so well in the twenty-first.

The 34 senators who object to UNCLOS are not unique in favoring sovereignty and freedom of action over working within a strategic environment. They are following in the footsteps of those senators after World War II who initially objected to the Marshall Plan, the Truman Doctrine, and new alliances because they imposed costs on the United States and violated its autonomy. U.S. President Harry Truman argued that these multilateral commitments were a part of an international order that would make the world safer for the United States. The positive case failed to convince the Senate. In response, Truman focused his energy on exploiting fear of the Soviet Union and managed to secure the necessary political support for his strategy. Fear won where hope could not.

Today, the positive case is again failing to convince the Senate. But unlike in the 1940s, fear will not work today. First, China is not nearly as threatening as the Soviet Union once was. Second, the United States and its friends in Asia need China to be a part of the solution. If it is not, Asia will be ripe for disruption and destabilization. That over one-third of the Senate fails to appreciate this is a cause for concern. And the blind spot is not confined to maritime security. For example, Washington should be pressing Beijing to participate in existing arms control agreements, such as the Intermediate-Range Treaty of Nuclear Forces, instead of objecting on principle to any treaty that constrains freedom of action. The Senate's intransigence, if it continues, will make new treaties practically useless as a tool of U.S. national security policy. President Obama and his successors will need to find ways to build multilateral structures through less formal partnerships and coalitions of the willing, which do not require Senate ratification, as well as existing structures such as the ARF. Although these options are important, they also have significant limitations and will not exert as much pressure on China to comply.

As holiday beaches go, this is an environmental and financial disaster. This may not be an immediate problem for UNCLOS enforcement, but it is evidence of a lack of local controls that is sure to lead to international law breaking.

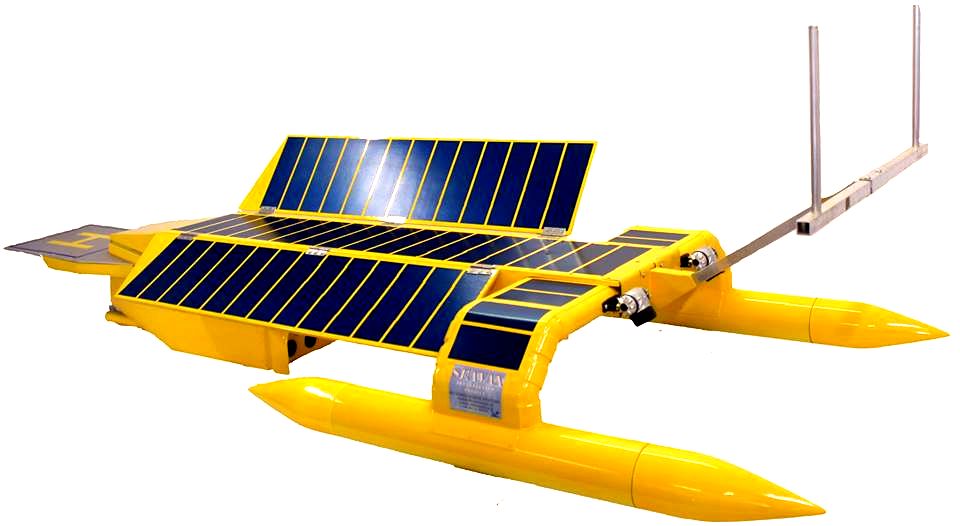

It all goes back to our dependence on oil. The by product, plastic, is so useful that we could not do without it today. For that reason, we need to take responsibility for our needs, by making provision to clean up our mess sustainably. We cannot afford fleets of trawlers manned by humans to scoop up the harmful soup, and that is where semi-autonomous robots could come to the rescue.

SEAVAX 'ENTERPRISE 1' - This is a proof of concept boat for a robot ship that is designed to vacuum up plastic waste from the ocean based on the Bluefish ZCC concept. The vessel is solar and wind powered. The front end (right) is modified so that there is a wide scoop area, into which plastic waste is funneled as the ship moves forward. The waste is pumped into a large holding bay after treatment, then stored until it can be off-loaded. The front of the ship carries two large wind turbines that generate electricity in combination with deck and wing mounted solar panels to power the onboard processing machinery. The system can be semi-autonomous, such that in robot mode the ships alert HQ to any potential problems and share data as to progress for backers. A whole cleanup mission can be controlled from land, with visuals and data streams. A SeaVax would operate using a search program called SeaNet.

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (Montego Bay, 10 December 1982)

Article

1. Use of terms and scope PART II. TERRITORIAL SEA AND CONTIGUOUS ZONE

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 2. Legal status of the territorial sea, of the air space over the territorial sea and of its bed and subsoil SECTION 2. LIMITS OF THE TERRITORIAL SEA Article

3. Breadth of the territorial sea SECTION 3. INNOCENT PASSAGE IN THE TERRITORIAL SEA Subsection A. Rules Applicable to all Ships Article

17. Right of innocent passage Subsection

B. Rules Applicable to Merchant Ships and Government Ships Article

27. Criminal jurisdiction on board a foreign ship Subsection

C. Rules Applicable to Warships and Other Government Ships Article

29. Definition of warships SECTION 4. CONTIGUOUS ZONE Article

33. Contiguous zone PART III. STRAITS USED FOR INTERNATIONAL NAVIGATION

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article

34. Legal status of waters forming straits used for international

navigation SECTION 2. TRANSIT PASSAGE Article

37. Scope of this section SECTION 3. INNOCENT PASSAGE Article

45. Innocent passage

Article

46. Use of terms PART V. EXCLUSIVE ECONOMIC ZONE

Article

55. Specific legal regime of the exclusive economic zone

Article

76. Definition of the continental shelf

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article

86. Application of the provisions of this Part SECTION

2. CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT OF THE Article

116. Right to fish on the high seas

Article

121. Regime of islands PART IX. ENCLOSED OR SEMI-ENCLOSED SEAS

Article

122. Definition PART X. RIGHT OF ACCESS OF LAND-LOCKED STATES TO AND FROM THE SEA AND FREEDOM OF TRANSIT

Article

124. Use of terms

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article

133. Use of terms SECTION 2. PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THE AREA Article

136. Common heritage of mankind SECTION 3. DEVELOPMENT OF RES0URCES OF THE AREA Article

150. Policies relating to activities in the Area SECTION 4. THE AUTHORITY Subsection A. General Provisions Article

156. Establishment of the Authority Subsection B. The Assembly Article

159. Composition, procedure and voting Subsection C. The Council Article

161. Composition, procedure and voting Subsection D. The Secretariat Article

166. The Secretariat Subsection E. The Enterprise Article 170. The Enterprise Subsection F. Financial Arrangements of the Authority Article

171. Funds of the Authority Subsection G. Legal Status, Privileges and Immunities Article

176. Legal status Subsection H. Suspension of the exercise of rights and privileges of Members Article

184. Suspension of the exercise of voting rights SECTION 5. SETTLEMENT OF DISPUTES AND ADVISORY OPINIONS Article

186. Sea-Bed Disputes Chamber of the International Tribunal for the Law of

the Sea

PART XII. PROTECTION AND PRESERVATION OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article

192. General obligation SECTION 2. GLOBAL AND REGIONAL CO-OPERATION Article

197. Co-operation on a global or regional basis SECTION 3. TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE Article

202. Scientific and technical assistance to developing States SECTION 4. MONITORING AND ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT Article

204. Monitoring of the risks or effects of pollution SECTION 5. INTERNATIONAL RULES AND NATIONAL LEGISLATION TO PREVENT, REDUCE AND CONTROL POLLUTION OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT Article

207. Pollution from land-based sources SECTION 6. ENFORCEMENT Article

213. Enforcement with respect to pollution from landbased sources SECTION 7. SAFEGUARDS Article

223. Measures to facilitate proceedings SECTION 8. ICE-COVERED AREAS Article 234. Ice-covered areas SECTION 9. RESPONSIBILITY AND LIABILITY Article 235. Responsibility and liability SECTION 10. SOVEREIGN IMMUNITY Article 236. Sovereign immunity SECTION 11. OBLIGATIONS UNDER 01 HER CONVENTIONS ON THE PROTECTION AND PRESERVATION OF THE MARINE ENVIRONMENT Article 237. Obligations under other conventions on the protection and preservation of the marine environment

PART XIII. MARINE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article

238. Right to conduct marine scientific research SECTION 2. INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION Article

242. Promotion of international co-operation SECTION

3. CONDUCT AND PROMOTION OF MARINE Article

245. Marine scientific research in the territorial sea SECTION

4. SCIENTIFIC IC RESEARCH INSTALLATIONS OR Article

258. Deployment and use SECTION 5. RESPONSIBILITY AND LIABILITY Article 263. Responsibility and liability SECTION

6. SETTLEMENT OF DISPUTES AND INTERIM Article

264. Settlement of disputes PART

XIV. DEVELOPMENT AND TRANSFER OF

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article

266. Promotion of the development and transfer of marine technology SECTION2. INTERNATIONAL CO-OPERATION Article

270. Ways and means of international co-operation SECTION

3. NATIONAL AND REGIONAL MARINE SCIENTIFIC Article

275. Establishment of national centres SECTION

4. CO-OPERATION AMONG INTERNATIONAL Article

278. Co-operation among international organizations PART XV. SETTLEMENT OF DISPUTES

SECTION 1. GENERAL PROVISIONS Article

279. Obligation to settle disputes by peaceful means SECTION

2. COMPULSORY PROCEDURES ENTAILING Article

286. Application of procedures under this section SECTION

3. LIMITATIONS AND EXCEPTIONS TO Article

297. Limitations on applicability of section 2

Article

300. Good faith and abuse of rights

Article

305. Signature

ANNEXES

I.

HIGHLY MIGRATORY SPECIES The States Parties to this Convention,

Prompted by the desire to settle, in a spirit of mutual understanding and co-operation, all issues relating to the law of the sea and aware of the historic significance of this Convention as an important contribution to the maintenance of peace, justice and progress for all the peoples of the world, Noting that developments since the United Nations Conferences on the Law of the Sea held at Geneva in 1958 and 1960 have accentuated the need for a new and generally acceptable Convention on the law of the sea, Conscious that the problems of ocean space are closely interrelated and need to be considered as a whole, Recognising the desirability of establishing, through this Convention, with due regard for the sovereignty of all States, a legal order for the seas and oceans which will facilitate international communication and will promote the peaceful uses of the seas and oceans, the equitable and efficient utilization of their resources, the conservation of their living resources and the study, protection and preservation of the marine environment, Bearing in mind that the achievement of these goals w ill contribute to the realization of a just and equitable international economic order which takes into account the interests and needs of mankind as a whole and, in particular, the special interests and needs of developing countries, whether coastal or land-locked, Desiring by this Convention to develop the principles embodied in resolution 2749 (XXV) of 17 December 1970 in which the General Assembly of the United Nations solemnly declared inter alia that the area of the sea-bed and ocean floor and the subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction, as well as its resources, are the common heritage of mankind, the exploration and exploitation of which shall be carried out for the benefit of mankind as a whole, irrespective of the geographical location of States, Believing that the codification and progressive development of the law of the sea achieved in this Convention will contribute to the strengthening of peace, security, co-operation and friendly relations among all nations in conformity with the principles of justice and equal rights and will promote the economic and social advancement of all peoples of the world, in accordance with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations as set forth in the Charter, Affirming

that matters not regulated by this Convention continue to be governed by

the rules and principles of general international law, Have

agreed as follows: PART I INTRODUCTION

Article 1. Use of terms and scope 1. For the purposes of this Convention: (1) 'Area' means the sea-bed and ocean floor and subsoil thereof, beyond the limits of national jurisdiction; (2) 'Authority' means the International Sea-Bed Authority; (3) 'activities in the Area' means all activities of exploration for, and exploitation of, the resources of the Area: (4) 'pollution of the marine environment' means the introduction by man, directly or indirectly, of substances or energy into the marine environment, including estuaries, which results or is likely to result in such deleterious effects as harm to living resources and marine life, hazards to human health, hindrance to marine activities, including fishing and other legitimate uses of the sea, impairment of quality for use of sea water and reduction of amenities; (5) (a) 'dumping' means: (i) any deliberate disposal of wastes or other matter from vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea; (ii) any deliberate disposal of vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea. (b) 'dumping' does not include: (i) the disposal of wastes or other matter incidental to, or derived from the normal operations of vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea and their equipment, other than wastes or other matter transported by or to vessels, aircraft, platforms or other man-made structures at sea, operating for the purpose of disposal of such matter or derived from the treatment of such wastes or other matter on such vessels, aircraft, platforms or structures; (ii) placement of matter for a purpose other than the mere disposal thereof, provided that such placement is not contrary to the aims of this Convention. 2. (1) 'States Parties' means States which have consented to be bound by this Convention and for which this Convention is in force. (2) This Convention applies mutatis mutandis to the entities referred to in Article 305, paragraph 1 (b), (c), (d), (e) and (f), which become Parties to this Convention in accordance with the conditions relevant to each, and to that extent 'States Parties' refers to those entities.

LINKS

Wikipedia List_of_parties_to_the_United_Nations_Convention_on_the_Law_of_the_Sea Wikipedia United_Nations_Convention_on_the_Law_of_the_Sea UNEP news centre conference heads of state commerce Foreign affairs articles oceans 2012-08-07 United States of America outlaws sea UN convention_agreements texts unclos The

Diplomat 2012 why-to-forget-unclos http://thediplomat.com/2012/02/why-to-forget-unclos/ https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/oceans/2012-08-07/outlaw-sea http://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_parties_to_the_United_Nations_Convention_on_the_Law_of_the_Sea http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Convention_on_the_Law_of_the_Sea http://www.unep.org/newscentre/Default.aspx?DocumentID=2791&ArticleID=10916&l=en http://www.unep.org/ http://www.unep.org/environmentunderreview/ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/04/140414-ocean-garbage-patch-plastic-pacific-debris/ http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0111913 http://www.roboticstomorrow.com/content.php?post_type=1919 http://www.dailydot.com/technology/ocean-cleaning-drone/ http://www.interiorholic.com/other/gadgets/ocean-robot-cleaner/ http://www.psfk.com/2012/07/marine-robots-clean-oceans.html http://www.unep.org/environmentunderreview/

ARCTIC - ATLANTIC - BALTIC - BERING - CARIBBEAN - CORAL - EAST CHINA - ENGLISH CH - GULF MEXICO GOC - INDIAN - MEDITERRANEAN - NORTH SEA - PACIFIC - PERSIAN GULF - SEA JAPAN - STH CHINA PLASTIC

OCEANS - UNEP

- WOC - WWF

Youtube ocean pollution

|

|||||||||

|

This website is Copyright © 2015 Bluebird Marine Systems Ltd. The names Bluebird™, Bluefish™, SeaVax™, SeaNet™ and the blue bird and fish in flight logos are trademarks. CONTACTS The color blue is a protected feature of the trademarks.

|