|

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION MARITIME AFFAIRS: MEDITERRANEAN SEA

Though the Mediterranean Sea is bounded by over 20 countries, much of it lies outside national jurisdictions. Cooperation is therefore essential to:

* manage maritime activities,

* protect the marine environment & maritime heritage

* prevent & combat pollution

* improve safety & security at sea

* promote blue growth & job creation.

In the Mediterranean region, the integrated maritime policy is designed to improve cooperation and governance while also encouraging

sustainable

growth. It encompasses the following:

The Working Groups for Integrated Maritime Policy in the Mediterranean, involving all the countries bordering on the Mediterranean and regional organisations, which meet annually.

Tripartite cooperation between the European Commission's Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, the European Investment Bank and the International Maritime Organisation - to develop maritime sectors in the Mediterranean, especially in the EU's southern partner countries. Following up this cooperation and the 12th FEMIP Conference, the 3 are working together with the secretariat of the Union for the Mediterranean and the countries concerned, on key ideas including:

1. developing maritime clusters

2. promoting a network of maritime training institutes and academies

3. developing a virtual knowledge centre for marine and maritime affairs in the Mediterranean.

The Project on Integrated Maritime Policy for the Mediterranean - a European Neighbourhood Policy Instrument project funded by southern countries designed to help the southern Neighbourhood countries develop integrated approaches to marine and maritime affairs.

Developing sub-regional strategies to exploit the strengths and address the weaknesses of particular maritime regions, e.g. the new

EU Strategy for the

Adriatic and Ionian region and its action plan.

Each year, the Mediterranean Coast Guard Functions Forum – a voluntary, independent and non-political body - brings together administrations, institutions and agencies working on coast guard issues from all Mediterranean countries. The forums are funded by the Commission's Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries.

Ongoing efforts to develop a Virtual Knowledge Centre for marine and maritime affairs in the Mediterranean, to consolidate and share general, technical and sectoral information. The Centre will improve synergies across initiatives and projects, facilitate coordination and cooperation, promote investment and innovation, and support maritime businesses.

JIYEH

- The Jiyeh Power Station oil spill is an environmental disaster caused by

the release of heavy fuel oil into the eastern Mediterranean after storage

tanks at the thermal power station in Jiyeh, Lebanon, 30 km (19 mi) south

of Beirut, were bombed by the Israeli Air force on July 14 and July 15,

2006 during the 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict. The plant's damaged tanks

leaked up to 30,000 tonnes of oil into the eastern Mediterranean Sea, A 10

km wide oil slick covered 170 km of coastline, and threatened Turkey and

Cyprus. The slick killed fish, threatened the habitat of endangered green

sea turtles, and potentially increased the risk of cancer.

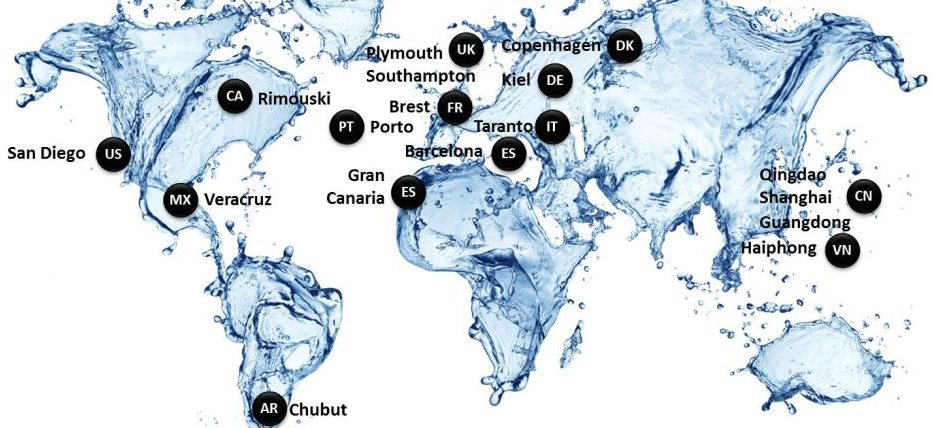

Two studies were published on the Maritime Forum in 2014:

(a) Support activities for the development of maritime clusters in the Mediterranean and

Black Sea - to map existing clusters, to identify the strengths and weaknesses of different types of clusters, and examine how feasible it is to develop national clusters and promote cluster cooperation at sub-regional levels | videos

(b) Mediterranean Sea – Identification of elements and geographical scope of maritime cooperation, part of a larger study on the growth potential of maritime businesses in the Mediterranean, Adriatic-Ionian and Black Seas. The aim is to assess existing maritime cooperation, highlight the added value of sea-basin/ sub-sea basin cooperation, and identify and propose the most suitable content, geographical scope and process for developing sea basin/ sub-sea basin cooperation further.

In 2015, the Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries will launch:

(a) a study on networking between maritime training academies and institutes in the Mediterranean region to assess whether and how such a network can be set up and whether it would have added value, as well as coastguard-related activities

(b) research work to help develop and innovate in the maritime economy through the Virtual Knowledge Centre for marine and maritime affairs in the Mediterranean.

Regional cooperation with Mediterranean partners

EU relations with the countries of the Southern Mediterranean and the Middle East have been developing through the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, established by the 1995 Barcelona Declaration. More recently, the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) has begun to map out relations between the EU and these regions.

The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership – or Barcelona Process – is a regional forum for political, economic and social cooperation, which sits alongside bilateral association agreements and ENP action plans. The process was re-launched when the Union for the Mediterranean was set up in 2008.

EU-funded

marine and maritime projects fall into a variety of policy areas. Examples

are:

Developing

a Mediterranean marine & coastal protected areas network (MedPAN South

Project)

Strengthening

cooperation in maritime safety & pollution prevention (SAFEMED

Project)

Supporting

the Integrated Maritime Policy for the Mediterranean (IMP-MED Project)

Maritime

Regions cooperation for the Mediterranean (MAREMED project)

ADRiatic

Ionian maritime spatial PLANning (ADRIPLAN project)

Policy-oriented

marine Environmental Research for the Southern European Seas (PERSEUS)

CREATION

- The European

Maritime Day (EMD) was officially created on 20 May 2008 where the

President of the European Parliament Hans-Gert Pöttering, Council

President Janez Janša, and Commission President José Manuel Barroso

signed a Joint Tripartite Declaration establishing it.

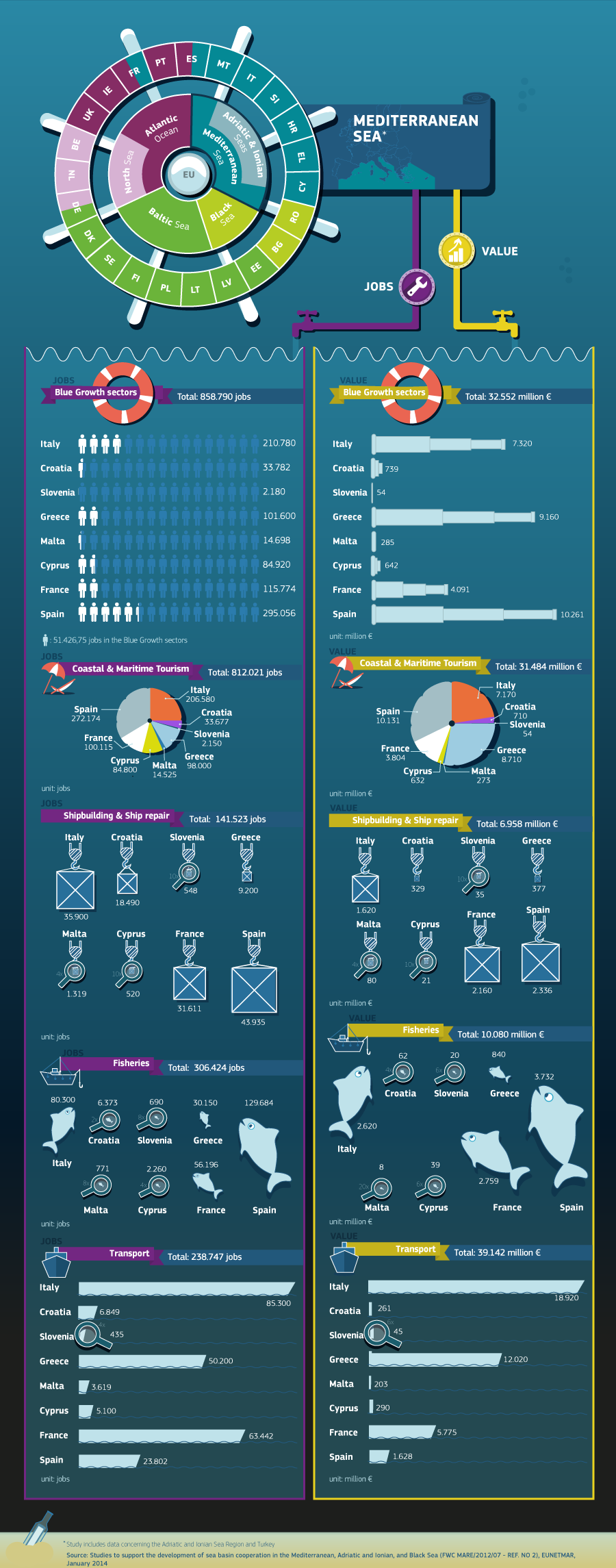

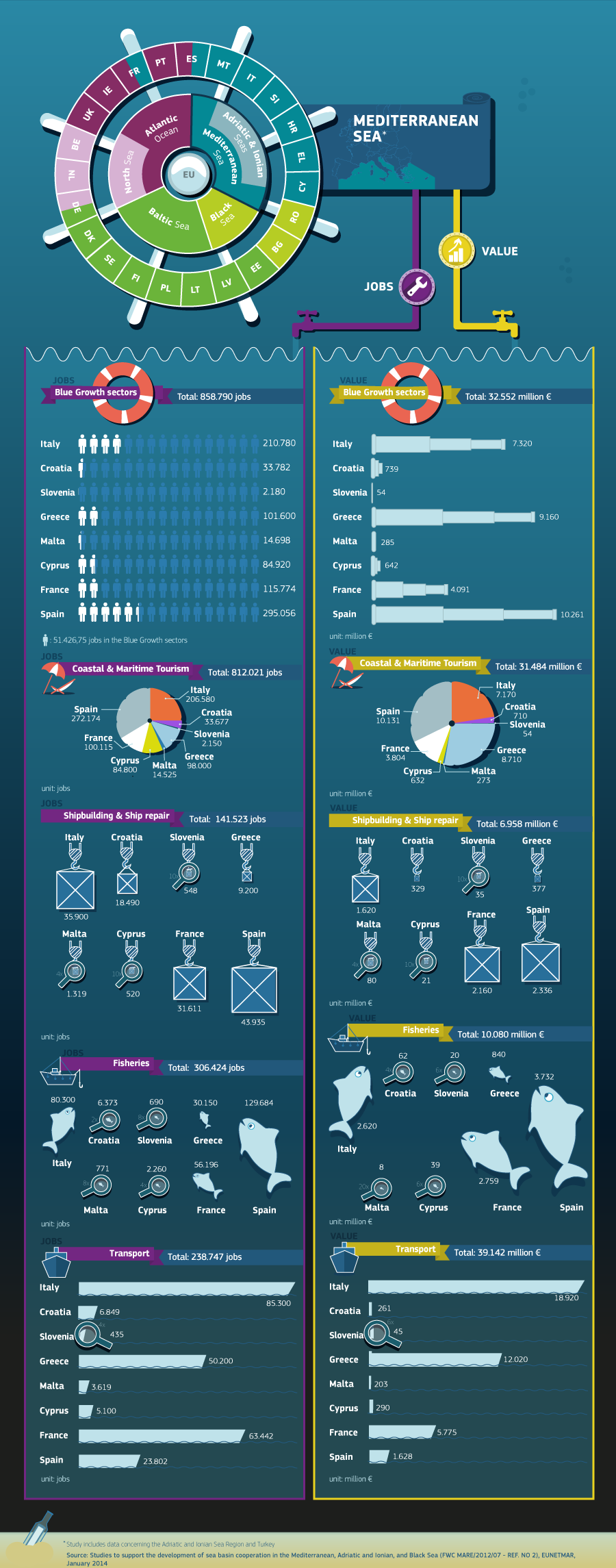

EU

BLUE GROWTH - PRESS

RELEASE, BRUSSELS 19 APRIL 2017

Today the European Commission launches a new initiative for the sustainable development of the blue economy in the Western Mediterranean region.

The region covers economic hubs like Barcelona, Marseille, Naples and Tunis. It also includes tourist destinations like the Balearic Islands, Sicily and Corsica.

The sea's biodiversity is under severe pressure with a recent report by scientists from the Joint Research Centre indicating that 50% has been lost in the last 50 years. In addition to this are recent security and safety concerns from the increase in migration from the South to the North.

This initiative will allow EU and neighbouring countries to work together to increase maritime safety and security, promote sustainable blue growth and jobs, and preserve ecosystems and biodiversity.

Karmenu Vella, Commissioner for Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries said: "Millions of holiday makers have a happy association with the Western Mediterranean. Like the millions more who live across the region, they understand the fragile link between conserving national habitats and traditions and ensuring economic viability. Blue economy is important for each of the countries involved and they have recognised the strength of working together."

Johannes Hahn, Commissioner for European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations, said: ''This new regional initiative recognises and taps into the economic potential of the Mediterranean Sea and its coast lines to further enhance economic growth, contribute to job creation and eventually the stabilisation of the region. It is an important step towards closer coordination and cooperation among participating countries."

The initiative is the fruit of years' of dialogue between ten countries of the Western Mediterranean region who are ready and willing to work together on these shared interests for the region: five EU Member States

(France, Italy,

Portugal,

Spain and Malta), and five Southern partner countries (Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia). It follows up on the Ministerial Declaration on Blue Economy endorsed by the Union for Mediterranean (UfM) on 17 November 2015.

The goals of the initiative

By fostering cooperation between the ten countries concerned, this initiative has three main goals:

1. A safer and more secure maritime space

2. A smart and resilient blue economy

3. Better governance of the sea.

Gaps and challenges have been identified and a number of priorities and targeted actions have been set for each goal.

For Goal 1 priorities include cooperation between national coast guards and the response to accidents and oil spills. Specific actions will focus on the upgrade of traffic monitoring infrastructure, data sharing and capacity building. For Goal 2 priorities include new data sourcing, biotechnology and coastal tourism. For Goal 3, priority is given to spatial planning, marine knowledge, habitat conservation and sustainable fisheries.

The initiative will be funded by existing international, EU, national and regional funds and financial instruments, which will be coordinated and complementary. This should create leverage and attract funding from other public and private investors

This "Initiative for the sustainable development of the blue economy of the Western Mediterranean" is another example of the EU's successful neighbourhood policy. Barely three weeks ago, the EU secured a 10-year pledge to save Mediterranean fish stocks. The MedFish4Ever Declaration, signed by Mediterranean ministerial representatives from both Northern and Southern coastlines on 30 March, involves 8 Member States (Spain, France, Italy, Malta, Slovenia, Croatia,

Greece, and

Cyprus) and 7 third countries (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia,

Egypt, Turkey, Albania, Montenegro). The two projects will enhance each other in protecting the region's ecological and economic wealth.

Background

The initiative is based on the Commission's long-standing experience with sea basin and macro-regional strategies (such as the Atlantic Strategy, the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region and the EU Strategy for the Adriatic and Ionian Region). It is also based on over two decades of work within the 5+5 Dialogue, which has created strong ties between the participating countries. Furthermore, the initiative builds on other EU policies linked to the region, such as the European Neighbourhood Policy Review priorities and the recent Communication on International Ocean Governance.

The initiative is presented in two documents. A Communication outlines the main challenges, shortcomings and the possible solutions. A Framework for Action presents the identified priorities, actions and projects in detail, with quantitative targets and deadlines to monitor progress over time. Some of the actions could extend well beyond the countries in question and even beyond the sub-basin.

MIGRATION

HOT SPOT

Record numbers of migrants are taking to the seas to escape political strife, sectarian conflict and war, crossing the Aegean and Mediterranean seas aboard inadequate vessels in search of better and safer lives for themselves and their families. Many are struggling to cope with the sheer numbers: from the coastal nations receiving desperate refugees, to the border management agencies, to the UN and the IMO, to the mariners at sea obligated by maritime tradition to rescue those in crisis on the water. In this episode of World Ocean Radio, host Peter Neill will discuss the complicated political, maritime and humanitarian crisis we now face.

TRANSCRIPT: I’m Peter Neill, Director of the World Ocean Observatory. We have seen the photographs and

television images of a bedraggled lot of refugees, far too many for their flimsy craft, seeking rescue at sea or asylum alongshore. The images reveal a very real compulsion to seek freedom or opportunity in a place across the water; the dangers are evident, the desperation is palpable.

Over the past decades, the situation has only gotten worse. The reports of stowaways aboard ships or in containers, and of the dead and missing at sea are increasing in many parts of the world, a refugee migration that has gone mostly undocumented until now. These voyages are always ill-prepared, complicated by lack of cover from the sun, fresh water, and food, by adverse weather and sea conditions, by the fundamental unseaworthiness of the vessels, by extreme over-crowding, and, by the involvement of unscrupulous intermediaries who prey upon the desperation, arrange the voyages, take the money, and abandon their clients almost certainly along the way.

Some nations have responded to the problem by enhancing monitoring and surveillance. FRONTEX, the European border management agency, launched the European Patrol Network to bolster security of the European Union’s southern coastal waters. The Network is also cooperating with several West African nations in an attempt to stem a new migration flow by boat from Africa to the Canary Islands. And, in the United States, the US Coast Guard has been incorporated into the Department of Homeland Security wherein refugee surveillance is included in its mandate to curtail illegal activities such as drug smuggling or terrorist activity in our coastal zone.

International law, indeed maritime tradition for all time, has firmly established the obligation to rescue persons at sea. But complex political conditions or the decision by certain countries not to disembark boat people on their shores has created disincentives for captains to assist vessels in distress or deliver refugees to safe harbor. Several reports from the Mediterranean where refugee craft were not offered rescue by shipmasters for these reasons. It seems unthinkable that such circumstances would compromise or prohibit a humanitarian response that lies at the core of values long demonstrated at extreme personal risk by mariners.

Moreover, in some instances, unreasonable fines have been imposed on ship-owners when passengers are found by public authorities to have inadequate documentation or are otherwise deemed inadmissible by the state. Most refugees, of course, have no passports or identification, and absurd administrative stalemates have occurred, with ships arrested in port with captain, crew, cargo, and refugees held for days in political limbo. As these migrations increase, it becomes more and more likely that, even if these refugees survive the dangers of their voyage, they will be immediately deported and sent home to face the consequence.

The International Maritime Organization and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees are convening meetings among the various agencies and nations for which this is an existing problem. With all the best intentions, they will work to regularize international response to maritime migration, but as long as there is conflict at home, as long as there is an alternative opportunity to be reached across the sea, if there is a boat to be had, men and women will launch it at whatever risk in search of a different shore.

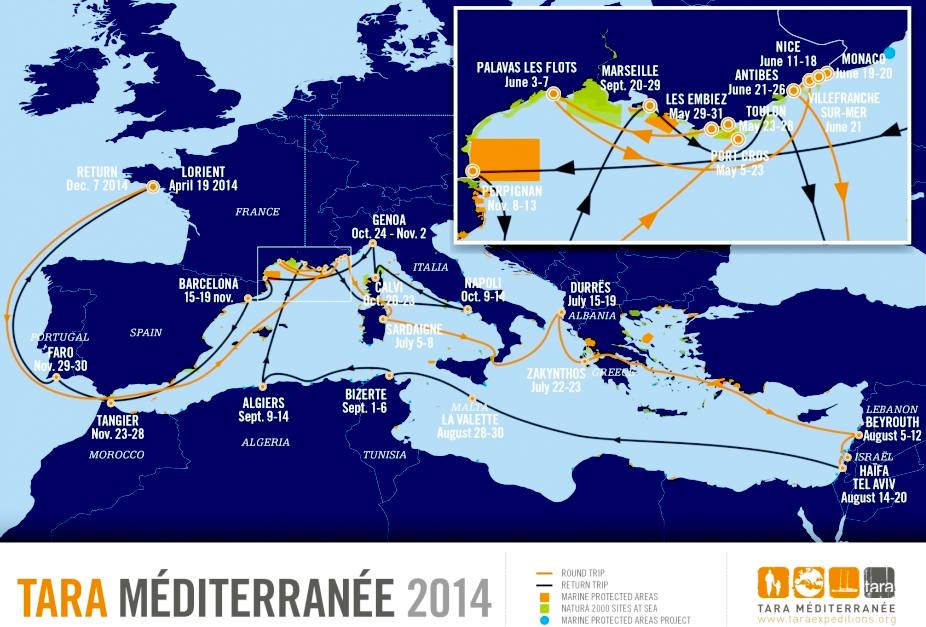

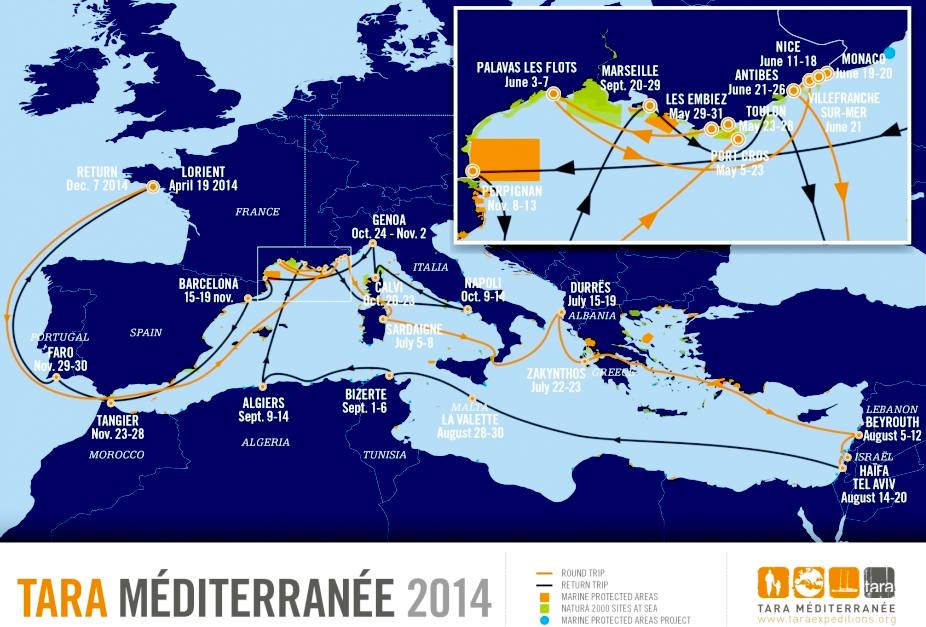

TARA

MEDITERRANEAN EXPEDITION 2014

The Mediterranean represents 0,8% of the world's total ocean area and hosts 8% of global marine biodiversity. However, pollution from saturated cities along the Mediterranean coasts from industries and from the world’s maritime traffic, 30of the world’s traffic, are putting pressure on the marine ecosystem.

Amongst this pollution is the increasing presence of micro-plastics and their possible inclusion in the marine food chain and therefore our food chain, which worries the scientific world.

Initiated by the "Tara Expeditions" endowment fund, this project is supported by several partners including the CNRS, the University of Maine and the University of Michigan in the

United

States. The program is backed by several multilateral institutions such as the MedPAN organization, the Union for the Mediterranean, the European Commission's Environment DG and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

(UNESCO/IOC).

The 2014 Tara Mediterranean expedition is preparing a mission with two objectives:

1. A scientific part which is consistent with a study aiming at qualifying and quantifying plastic fragments, and measuring size and weight. The findings of this study, headed by the University of Michigan (USA) and the Villefranche-sur-Mer Oceanography Laboratory (CNRS), will help to better guide the decision makers in the 22 bordering countries to oversee the risks of pollution on the Mediterranean ecosystem.

2. The expedition has a purpose of helping to raise the environmental awareness of the general public on challenges in the Mediterranean. At each stopover, a traveling exhibition and films will be shared with the public. Furthermore, classes from local schools will be welcomed aboard. During the whole expedition, artists will be reporting about their experiences.

TARA

- DECEMBER 2014 IMPORTANT INITIAL FINDINGS

The strategy of the Tara Mediterranean expedition was to collect samples offshore, but also along the coasts, near the mouths of rivers,and in harbors, to study influences coming from land. At each sampling station, collection was done at the surface using special nets. The samples will be sent to partner laboratories for chemical identification of the collected

plastic, analysis by microscopy, and also for studiesof the living organisms colonizing the plastic, and the interaction between zooplankton (the base of the marine food chain) and plastic.

Analyses of samples will begin in December, and the first results will be published in spring 2015. But the initial findings ofTara Mediterranean are highly significant !

According to Tara Mediterranean’s scientific director Gaby Gorsky (CNRS/UPMC), and the expedition’s scientific coordinator Maria Luiza Pedrotti (OOV CNRS/ UPMC), “Plastic fragments were found in every net haul, throughout the entire Mediterraneanfrom west to east. Greater concentrations of plastic were observed near big cities, but there were also significant

concentrations in the high seas.” Martin Hertau, one of Tara’s two captains, confirmed,

“We thought certain areas very far from big cities would be spared, but even these are affected, for example between Crete and Tunisia.” According to Francois Galgani, researcher atIfremer, “The Mediterranean Sea has, on average, the world’s highest density of microplastic.”

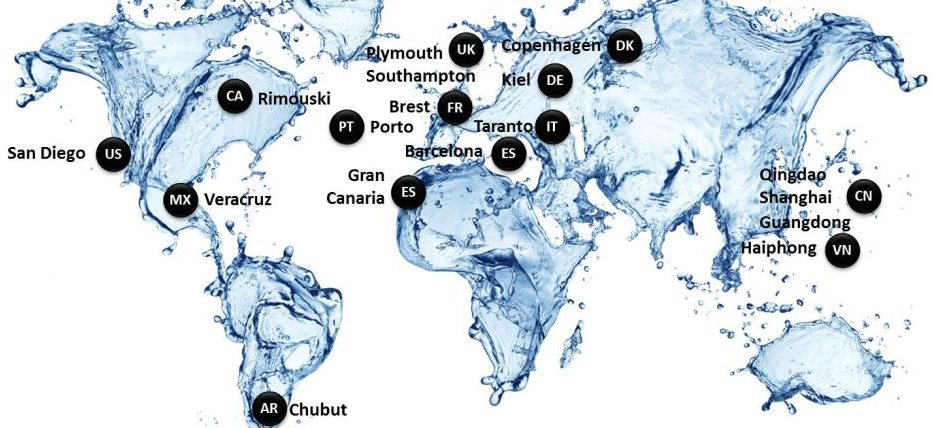

The Tara Mediterranean expedition, the 10th for Tara since 2003, visited 13 countries with 20 stopovers (in France, Italy,Monaco, Albania, Greece, Lebanon,

Cyprus, Malta, Tunisia, Algeria,

Spain, Morocco and Portugal). Nearly 12,000 adults and school children from around the Mediterranean were able to visit the schooner.

Five workshops were conducted with local citizens, experts and policy makers in order to foster international cooperation and on-site projects. There is an urgent need to move towards solutions such as water treatment, waste management, innovation for biodegradable plastic, and promoting sustainable tourism, education and the creation of Marine Protected Areas. A “Blue Book” to be released in March will highlight local initiatives and solutions, and will review the exchanges accomplished during the Tara Mediterranean mission.

The

exploration schooner Tara returns to her home port of Lorient on November 22 (the first day of “European Waste Reduction Week”) after successfully completing an expedition in the Mediterranean from May to November 2014. This expedition included scientific research about plastic pollution at sea, and educational outreach during stopovers concerning the many environmental issues related to the Mediterranean.

TARA

BEYOND THE FACTS - WHAT SOLUTIONS ?

Plastic in the Mediterranean : March 10 – 11, 2015, Tara Expeditions will organize with the Surfrider Association and the Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation a conference entitled: “Plastic in the Mediterranean: Beyond the Facts,

What

Solutions?”

The purpose of the conference is to initiate a dialogue between participants (industry, civil society, citizens, scientists and politicians) and to develop actions to curb plastic pollution. This conference, open to the general public, and will take place in Monaco.

TARA SCHOONER EXPEDITION PARTNERS

Fondation Veolia, IDEC Group, Serge Ferrari, Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, Lorient Agglomeration, IOC/UNESCO, CNRS, UPMC, University of Maine, University of Michigan,

NASA, AFP, Le Monde, RFI, FRANCE 24, MCD, Le Monde Futura Science, MedPAN, European Surfrider Foundation, Oceanographic Observatory of Villefranche-sur-mer, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Free University of Berlin, IFREMER, Oceanographic Observatory of Banyuls, University of South Brittany, University of South Toulon, Aix MarseilleUniversity, University of Corsica.

JULY

2014 - FISH STOCKS SHOW STEADY DECLINE

Careful management has helped

to stabilize or even improve the state of fisheries resources in some parts of Europe,

but the situation in the Mediterranean has deteriorated over the past 20 years. In a

report evaluating nine fish species reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on July 10, scientists call for stringent monitoring of Mediterranean fishing activities, better enforcement of fisheries regulations, and advanced management plans in Mediterranean waters.

Their data show that the fishing pressure in the Mediterranean intensified continuously from 1990 to 2010, with more and more fish caught as juveniles. If those young fish were allowed to reach maturity and reproduce at least once, it would greatly improve Mediterranean

fish stocks.

Paraskevas Vasilakopoulos of the Hellenic Centre for Marine Research is

quoted as saying: "It is time for the European Union and regional governments to start taking Mediterranean fisheries research and management more seriously,"

"Bigger investments are needed to improve Mediterranean fisheries research through the collection and analysis of good quality data regarding the biology and exploitation of Mediterranean fish stocks."

Vasilakopoulos, along with colleagues Christos Maravelias and George Tserpes, analyzed European Mediterranean fish stocks representing nine species from 1990 to 2010 to show that the exploitation rate has steadily increased as selectivity has deteriorated and stocks have dwindled. Species-specific simulation models show that stocks would be more resilient to fishing and produce higher long-term yields if harvested a few years after fish reach reproductive maturity. That's especially true for species such as hake and red mullet, which live at or near the bottom of the sea and are often scooped up by trawl nets in very large numbers.

There are some obvious reasons why Mediterranean fisheries have been conveniently overlooked, Vasilakopoulos

explained. Mediterranean fisheries include a greater diversity of species and gear used to catch fish in comparison to fisheries of the northeast Atlantic. Most Mediterranean fishing

vessels - more than 95% - operate on a small scale over a vast coastline, making monitoring and enforcement a great challenge. Those difficulties are compounded by financial constraints in many Mediterranean countries.

The researchers say that many more fish species are likely to be in a similar state of decline, both in the Mediterranean and in seas of other resource-limited regions of the world, including China, sub-Saharan Africa, and the tropics.

"The European Common Fisheries Policy that has assisted in improving the state of NE Atlantic fish stocks in the past 10 years has failed to deliver similar results for Mediterranean stocks managed under the same policy," the researchers

wrote. "Limiting juvenile exploitation, advancing management plans, and strengthening compliance, control, and enforcement could promote fisheries sustainability in the Mediterranean."

IMPROVING

GOVERNANCE: OPPORTUNITY FOR BLUE GROWTH - 15

July 2013

A

new study presented by the European Commission finds that the

establishment of maritime zones, including Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs),

in the Mediterranean would benefit the EU's Blue Growth and wider

sustainability agendas. The study looks at the costs and benefits of

establishing maritime zones in the Mediterranean and provides an analysis

of the impacts of establishing EEZs on different sea-based activities.

EEZs could allow for a more effective spatial planning policy, which in

turn could help attract investments and further economic activities.

Maria

Damanaki, European Commissioner for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries stated:

"There are huge untapped opportunities in the

Mediterranean Sea, which could come to fruition by establishing Exclusive

Economic Zones (EEZs). The proclamation and establishment of maritime

zones remains the sovereign right of each coastal State. It is our joint

EU responsibility to ensure that the right conditions are in place for the

blue economy to flourish. Mediterranean coastal states could agree on

their maritime zones on the basis of the United Nations Convention on the

Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)."

The

study focuses on the opportunities which EEZs and other similar zones

would bring in terms economic costs and benefits, sustainability and

governance of marine space and should be viewed in the context of the

European Commission's Blue Growth agenda.

The

EU Blue Growth Strategy aims at creating sustainable economic growth and

employment in the marine and maritime economy to help Europe's economic

recovery. These economic sectors provide jobs for 5.4 million people and

contribute a total gross value added of around 500 billion euros. By 2020,

these should increase to 7 million and nearly 600 billion euros

respectively. It highlights the five areas with the greatest potential for

growth: blue energy, aquaculture, maritime, coastal and cruise tourism,

marine mineral resources and blue

biotechnology.

Background

In

the Mediterranean as in other sea-basins, coastal states have a

responsibility to regulate human activities and to further develop their

blue economy in a sustainable manner.

A

large part of the Mediterranean sea surface is currently beyond the

jurisdiction or sovereignty of coastal States. It remains therefore

largely unprotected as far as living aquatic resources and the marine

environment are concerned. At the same time, proper economic development

is difficult in an uncertain regulatory framework.

In

2002, at the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg, the

global community committed to maintain the productivity and biodiversity

of important and vulnerable marine and coastal areas, both within and

beyond national jurisdiction. However, there is no specific legal regime

for implementing the relevant provisions of the UN Convention on the Law

of the Sea (UNCLOS), particularly in relation to the protection of the

marine environment in the areas beyond national jurisdiction. This issue

has been discussed at the UN since 2006.

The

coverage of a greater portion of the Mediterranean Sea under the

jurisdiction of the EU Member States would ensure that in such areas, EU

regulations concerning fisheries, environment and transport would apply

and a higher level of protection would follow.

More

information

The

final report and executive summary of the study may be found at:

http://ec.europa.eu/study-maritime-zones-in-mediterranean-sea_en.htm

GEOGRAPHY

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the

Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant. The sea is sometimes considered a part of the Atlantic Ocean, although it is usually identified as a completely separate body of water.

The name Mediterranean is derived from the Latin mediterraneus, meaning "inland" or "in the middle of the land" (from medius, "middle" and terra, "land"). It covers an approximate area of 2.5 million km² (965,000 sq mi), but its connection to the Atlantic (the Strait of Gibraltar) is only 14 km (8.7 mi) wide. In oceanography, it is sometimes called the Eurafrican Mediterranean Sea or the European Mediterranean Sea to distinguish it from mediterranean seas elsewhere.

The Mediterranean Sea has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,267 m (17,280 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea.

It was an important route for merchants and travellers of ancient times that allowed for trade and cultural exchange between emergent peoples of the region. The history of the Mediterranean region is crucial to understanding the origins and development of many modern societies.

The Mediterranean Sea is connected to the Atlantic Ocean by the Strait of Gibraltar in the west and to the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, by the Dardanelles and the Bosporus respectively, in the east. The Sea of Marmara is often considered a part of the Mediterranean Sea, whereas the Black Sea is generally not. The 163 km (101 mi) long man-made Suez Canal in the southeast connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea.

Large islands in the Mediterranean include Cyprus, Crete, Euboea, Rhodes, Lesbos, Chios, Kefalonia, Corfu, Limnos, Samos, Naxos and Andros in the eastern Mediterranean; Sardinia, Corsica, Sicily, Cres, Krk, Brač, Hvar, Pag, Korčula and Malta in the central Mediterranean; and Ibiza, Majorca and Minorca (the Balearic Islands) in the western Mediterranean.

The typical Mediterranean climate has hot, dry summers and mild, rainy winters. Crops of the region include olives, grapes,

oranges, tangerines, and cork.

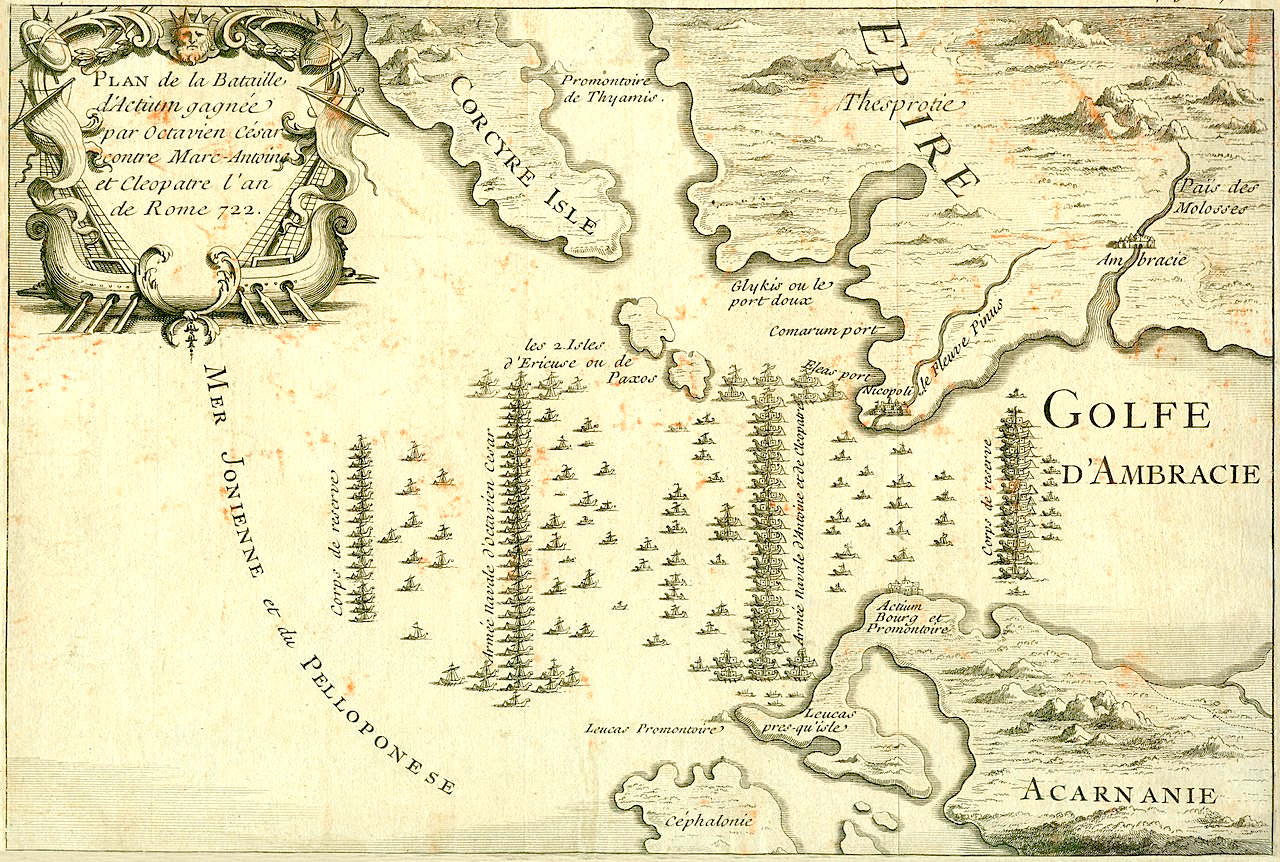

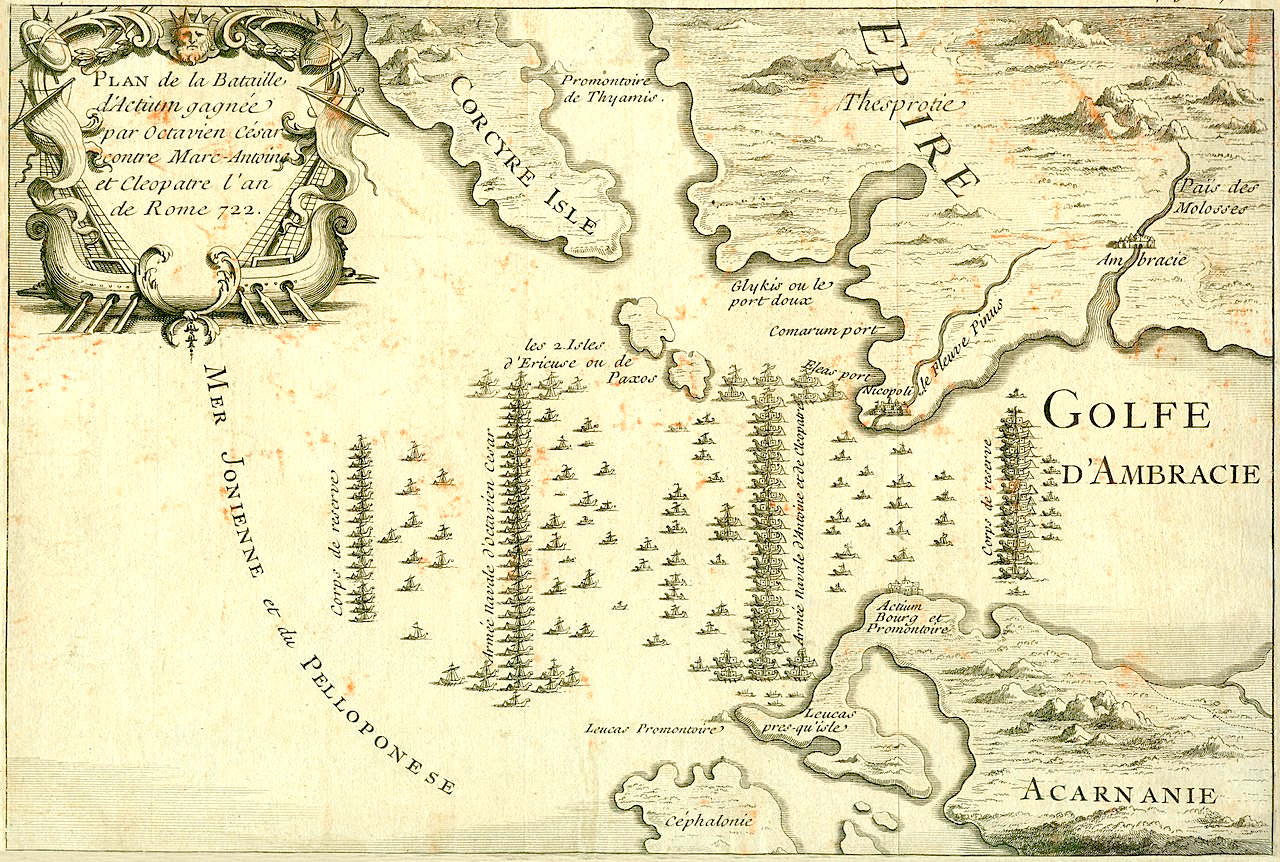

FAMOUS

HISTORIC BATTLE 31BC

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between a maritime fleet led by Octavian and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and

Cleopatra VII

Philopator. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former Roman colony of Actium, Greece, and was the climax of over a decade of rivalry between Octavian and

Mark

Antony.

In early 31 BC, the year of the battle, Antony and Cleopatra were temporarily stationed in Greece. Mark Antony possessed 500 ships and 70,000 infantry, and made his camp at Actium, and Octavian, with 400 ships and 80,000 infantry, arrived from the north and occupied Patrae and Corinth, where he managed to cut Antony’s southward communications with Egypt (via the Peloponnese) with help from Marcus Agrippa. Octavian previously gained a preliminary victory in Greece, where his navy successfully ferried troops across the Adriatic Sea under the command of Marcus Agrippa. Octavian landed on mainland Greece, opposite of the island of Corcyra (modern Corfu) and proceeded south, on land.

Trapped on both land and sea, portions of Antony's army deserted and fled to

Octavian's side, and Octavian's forces became comfortable enough to make preparations for battle. Antony's fleet sailed through the bay of Actium on the western coast of Greece, in a desperate attempt to break free of the naval blockade. It was there that Antony's fleet faced the much larger fleet of smaller, more manoeuvrable ships under commanders Gaius Sosius and Agrippa. Antony and his remaining forces were spared only due to a last-ditch effort by

Cleopatra's fleet that had been waiting nearby. Octavian pursued them and defeated their forces in

Alexandria on 1 August 30 BC—after which Antony and

Cleopatra committed suicide.

Octavian's victory enabled him to consolidate his power over Rome and its dominions. He adopted the title of Princeps ("first citizen"), and in 27 BC was awarded the title of Augustus ("revered") by the Roman Senate. This became the name by which he was known in later times. As Augustus, he retained the trappings of a restored Republican

leader. Historians view his consolidation of power as the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire.

BIODIVERSITY

- Compared to other regions of the world and considering its small dimension (less than 1% of the worlds ocean area), our sea - Mare nostrum – contains 7% of all known marine species and is inhabited by unique and diverse forms of life. The Mediterranean Sea was defined as a biodiversity hotspot for conservation priorities given its high level of endemism, ranging between 20-30%, its threatened species, and also for the human pressure it has undergone over the centuries.

The Marine Programme initiative is implemented in close collaboration with a number of working groups including the IUCN Global Marine Programme, the World Commission on Marine Protected Areas, the Marine Mediterranean Group, the Species Survival Commission, the Mediterranean Species Programme, the Tropical Marine Ecosystems Working Group, the Commission on Ecosystem Management, and the Business and Biodiversity Programme.

OCEANOGRAPHY

Being nearly landlocked affects conditions in the Mediterranean Sea: for instance, tides are very limited as a result of the narrow connection with the Atlantic Ocean. The Mediterranean is characterized and immediately recognised by its deep blue

colour.

Evaporation greatly exceeds precipitation and river runoff in the Mediterranean, a fact that is central to the water circulation within the basin. Evaporation is especially high in its eastern half, causing the water level to decrease and salinity to increase eastward. This pressure gradient pushes relatively cool, low-salinity water from the Atlantic across the basin; it warms and becomes saltier as it travels east, then sinks in the region of the Levant and circulates westward, to spill over the Strait of Gibraltar. Thus, seawater flow is eastward in the Strait's surface waters, and westward below; once in the Atlantic, this chemically distinct Mediterranean Intermediate Water can persist thousands of kilometres away from its source.

RECENT HISTORY

For 4,000 years, human activity has transformed most parts of Mediterranean Europe, and the "humanisation of the landscape" overlapped with the appearance of the present Mediterranean climate. The image of a simplistic, environmental determinist notion of a Mediterranean Paradise on Earth in antiquity, which was destroyed by later civilisations dates back to at least the eighteenth century and was for centuries fashionable in archaeological and historical circles. Based on a broad variety of methods, e.g. historical documents, analysis of trade relations, floodplain sediments, pollen, tree-ring and further archaeometric analyses and population studies, Alfred Thomas Grove and Oliver Rackham's work on "The Nature of Mediterranean Europe" challenges this common wisdom of a Mediterranean Europe as a "Lost Eden", a formerly fertile and forested region, that had been progressively degraded and desertified by human

mismanagement. The belief stems more from the failure of the recent landscape to measure up to the imaginary past of the classics as idealised by artists, poets and scientists of the early modern Enlightenment.

The historical evolution of climate, vegetation and landscape in southern Europe from prehistoric times to the present is much more complex and underwent various changes. For example, some of the deforestation had already taken place before the Roman age. While in the Roman age large enterprises as the Latifundiums took effective care of forests and agriculture, the largest depopulation effects came with the end of the empire.

Some scientists assume that the major deforestation took place in modern times — the later usage patterns were also quite different e.g. in southern and northern Italy. Also, the climate has usually been unstable and showing various ancient and modern "Little Ice Ages", and plant cover accommodated to various extremes and became resilient with regard to various patterns of human activity.

Humanisation was therefore not the cause of

climate change but followed it. The wide ecological diversity typical of Mediterranean Europe is predominantly based on human behaviour, as it is and has been closely related human usage patterns. The diversity range was enhanced by the widespread exchange and interaction of the longstanding and highly diverse local agriculture, intense transport and trade relations, and the interaction with settlements, pasture and other land use. The greatest human-induced changes, however, came since World War II, respectively in line with the '1950s-syndrome' as rural populations throughout the region abandoned traditional subsistence economies. Grove and Rackham suggest that the locals left the traditional agricultural patterns towards taking a role as scenery-setting agents for the then much more important (tourism) travellers. This resulted in more monotonous, large-scale formations. Among further current important threats to Mediterranean landscapes are overdevelopment of coastal areas, abandonment of mountains and, as mentioned, the loss of variety via the reduction of traditional agricultural occupations.

POLLUTION

Pollution in this region has been extremely high in recent years. The

United Nations Environment Programme has estimated that 650,000,000 t (720,000,000 short tons) of sewage, 129,000 t (142,000 short tons) of mineral oil, 60,000 t (66,000 short tons) of mercury, 3,800 t (4,200 short tons) of lead and 36,000 t (40,000 short tons) of phosphates are dumped into the Mediterranean each year. The Barcelona Convention aims to 'reduce pollution in the Mediterranean Sea and protect and improve the marine environment in the area, thereby contributing to its sustainable development.' Many marine species have been almost wiped out because of the sea's pollution. One of them is the Mediterranean Monk

Seal which is considered to be among the world's most endangered marine mammals.[

The Mediterranean is also plagued by marine debris. A 1994 study of the seabed using trawl nets around the coasts of Spain,

France and Italy reported a particularly high mean concentration of debris; an average of 1,935 items per km². Plastic debris accounted for 76%, of which 94% was plastic bags.

SHIPPING

Some of the world's busiest shipping routes are in the Mediterranean Sea. It is estimated that approximately 220,000 merchant vessels of more than 100 tonnes cross the Mediterranean Sea each year—about one third of the world's total merchant shipping. These ships often carry hazardous cargo, which if lost would result in severe damage to the marine environment.

The discharge of chemical tank washings and oily wastes also represent a significant source of marine pollution. The Mediterranean Sea constitutes 0.7% of the global water surface and yet receives 17% of global marine

oil pollution. It is estimated that every year between 100,000 t (98,000 long tons) and 150,000 t (150,000 long tons) of crude oil are deliberately released into the sea from shipping activities.

Approximately 370,000,000 t (360,000,000 long tons) of oil are transported annually in the Mediterranean Sea (more than 20% of the world total), with around 250-300 oil tankers crossing the Sea every day. Accidental oil spills happen frequently with an average of 10 spills per year. A major

oil spill could occur at any time in any part of the Mediterranean.

TOURISM

With a unique combination of pleasant climate, beautiful coastline, rich history and diverse culture the Mediterranean region is the most popular tourist destination in the

world - attracting approximately one third of the world's international tourists.

Tourism is one of the most important sources of income for many Mediterranean countries. It also supports small communities in coastal areas and islands by providing alternative sources of income far from urban centres. However, tourism has also played major role in the degradation of the coastal and marine environment. Rapid development has been encouraged by Mediterranean governments to support the large numbers of tourists visiting the region each year. But this has caused serious disturbance to marine habitats such as erosion and pollution in many places along the Mediterranean coasts.

Tourism often concentrates in areas of high natural wealth, causing a serious threat to the habitats of endangered Mediterranean species such as sea turtles and monk seals. Reductions in natural wealth may reduce incentives for tourists to visit.

OVER FISHING

Fish stock levels in the Mediterranean Sea are alarmingly low. The European Environment Agency says that over 65% of all fish stocks in the region are outside safe biological limits and the

United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation, that some of the most important

fisheries - such as albacore and bluefin

tuna, hake, marlin, swordfish, red mullet and sea bream - are threatened.

There are clear indications that catch size and quality have declined, often dramatically, and in many areas larger and longer-lived species have disappeared entirely from commercial catches.

Large open water fish like tuna have been a shared fisheries resource for thousands of years but the stocks are now dangerously low. In 1999,

Greenpeace published a report revealing that the amount of bluefin tuna in the Mediterranean had decreased by over 80% in the previous 20 years and government scientists warn that without immediate action the stock will collapse.

MEDITERRANEAN

SCIENCE COMMISSION

The Mediterranean Science Commission, or Commission Internationale pour l'Exploration Scientifique de la Méditerranée (CIESM), is a commission created in

Madrid,

Spain, in 1919 to undertake multilateral international research on marine science in the Mediterranean Sea. The organization was founded by countries that border the sea and is now open to all countries engaged in scientific research in the sea. The CIESM aims to develop scientific cooperation through promoting international use of national research stations. The CIESM is an intergovernmental body with 23 member states that mostly border the Mediterranean coast.

Professors, (Italian) Decio Vinciguerra and

(German) Otto Krümmel, thought it would be useful for the fishing industry to promote oceanographic exploration of the Mediterranean Sea. Based on Vinciguerra's proposal, the 9th International Geographical Union in Geneva endorsed the principle of a commission in July 1908 and decided a committee should define the organization. The committee was formed and first met in Monaco on 30 March 1910 under the chairmanship of

Albert I, Prince of

Monaco, in the premises of the recently created

Oceanographic Museum.

GUARDIAN

APRIL 2015 - HUMAN MIGRATION, PEOPLE SMUGGLING

Just as the evening light began to dim at the fishing port in Zuwara, a blue wooden boat with a slim white stripe began to slide silently from the quay. Seventeen or 18 metres long, there was little to distinguish it from the dozens of other boats moored nearby. It looked like a fishing boat, and it moved like one, too.

But watching from the quay, a passing diesel smuggler picked it out easily. It was an odd time of day to go fishing, he says. The day before, that boat might have carried hundreds of fish back to port. This night, it would bear hundreds of refugees towards Italy. A day after 800 people drowned in nearby waters, yet another trip was following in its wake.

“That’ll carry 200,” says the smuggler. “Minimum.”

PEOPLE

SMUGGLERS - are using Facebook to lure migrants into 'Italy trips' Using phrases more suited to tourist magazines and images of luxury yachts. The smugglers based in Egypt and Turkey openly advertise their services on social media.

It reads like the website of a travel agency: “A trip to Italy next week in a big fast tourist yacht,” says the Facebook post beneath a picture of a luxury ocean liner. “Two floors, air-conditioned, prepared for tourists. Recommended for families.”

But a package holiday this is not. It is the Facebook page of a Turkey-based people smuggler, one of dozens if not hundreds of smugglers using the social network to advertise their services in plain sight. Once contactable only through trusted third parties, now smugglers along the southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean are openly publicising their phone numbers, prices and schedules on social media to drum up business.

The names of their pages euphemistically conjure images of tourism companies or advocacy groups, rather than smuggling routes that are bearing record numbers of migrants across the Mediterranean.

“Asylum and immigration to all of Europe – helping people in immigration and asylum” is the tagline for a second Turkish network. A third group, “Travel aid”, offers fake visas and passports, while a fourth smuggler, based in

Egypt, calls his group “The way to Europe”, and illustrates its page with an image of Moses parting the Red Sea.

Different smugglers use their groups for slightly different purposes. Some simply advertise specific trips (in one network, speedboats from Turkey to Greece are listed as €1,500 (£1,100) per person, and cargo boats to Italy cost €6,500, with children half-price). Several smugglers use their pages to liveblog the progress of their clients across the sea. Other groups constitute a chatroom for migrants to share stories and advice. And many pages are used by smugglers to assuage concerns over migrant safety – with varying degrees of credibility.

“Very safe” reads the slogan overlaid on a picture of a boat used by a well-known Egyptian smuggler, Abu

Alaa. It looks old and rusty, but Abu Alaa – a pseudonym that means “Alaa’s father” – uses this to his advantage. “It may not look pretty, but it’s perfect,” he continues. “It’s like a good suit you’d wear to a

wedding. All its parts are made from iron.”

It was a scene whose subtlety encapsulates the problem of dealing with the Mediterranean migration crisis by targeting individual smugglers and their

boats. Shortly before this boat left its moorings on Monday, the EU said it would launch military operations against smugglers who are based in places like Zuwara, the starting point for smuggling in Libya. Late on Thursday night, the head of the European commission, Donald Tusk, confirmed that plan, promising to “capture and destroy vessels used by the smugglers before they can be used”.

But interviews with one former and two current smugglers show therein lies a problem. Smuggling boats start life as

fishing trawlers. The moment of transition from the latter to the former is informal and almost imperceptible to outsiders.

As the boat in Zuwara shows, smugglers do not maintain a separate, independent harbour of clearly marked vessels, ready to be targeted by EU air strikes. They buy them off fishermen at a few days’ notice. To destroy their potential pool of boats, the EU would need to raze whole fishing ports.

by Patrick Kingsley

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Theguardian

World 2015 April 24 Libyas people smugglers how will they catch us theyll

soon move on The

Guardian world news 2015 May 8 people smugglers using facebook to lure

migrants into Italy trips Oceans

Tara expeditions Fondation

Veolia Nettuno

trieste edios IUCN

about union secretariat mediterranean programme marine_protected_areas Wikipedia

Mediterranean_Science_Commission CIESM Phys

news 2014 Mediterranean fish stocks steady decline

The-Veolia-Foundation-supports-the-Tara-Ocean-expedition-in-the-Mediterranean-in-2014

Wikipedia

International_Convention_for_the_Safety_of_Life_at_Sea

Wikipedia

Mediterranean_Sea

Encyclopedia

Mediterranean_Sea

World

Atlas mediterranean sea The

terramar project daily catch migrants at sea http://planbleu.org/en/launch-blue-growth-community-mediterranean

http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-17-924_en.htm

http://theterramarproject.org/thedailycatch/migrants-at-sea/

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Mediterranean_Sea.aspx

http://www.worldatlas.com/aatlas/infopage/medsea.htm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mediterranean_Sea

http://www.enterprise-europe-scotland.com/sct/news/?newsid=4538

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Convention_for_the_Safety_of_Life_at_Sea

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/24/libyas-people-smugglers-how-will-they-catch-us-theyll-soon-move-on http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/may/08/people-smugglers-using-facebook-to-lure-migrants-into-italy-trips http://oceans.taraexpeditions.org/ http://www.fondation.veolia.com/ http://nettuno.ogs.trieste.it/edios/main.htm http://www.iucn.org/about/union/secretariat/offices/iucnmed/iucn_med_programme/marine_programme/marine_protected_areas/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mediterranean_Science_Commission http://www.ciesm.org/ http://phys.org/news/2014-07-mediterranean-fish-stocks-steady-decline.html

http://www.theguardian.com/profile/patrick-kingsley

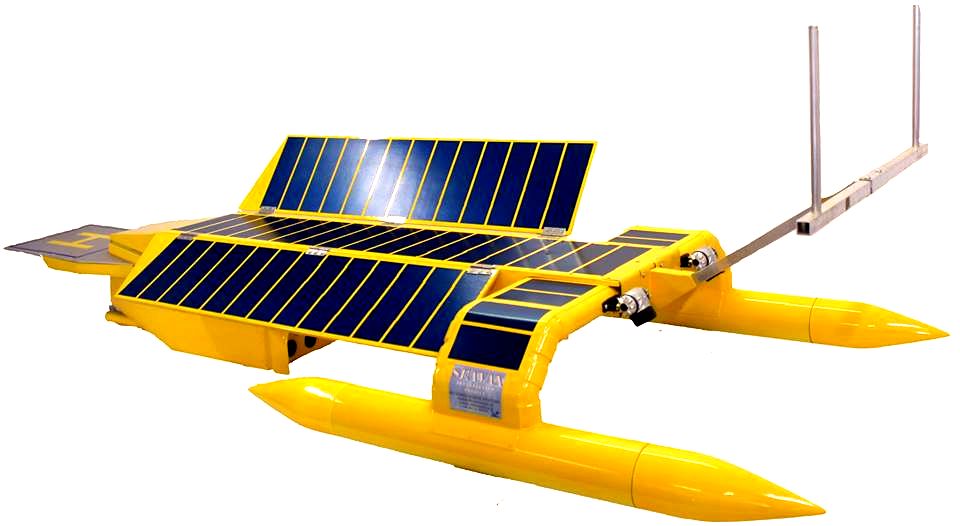

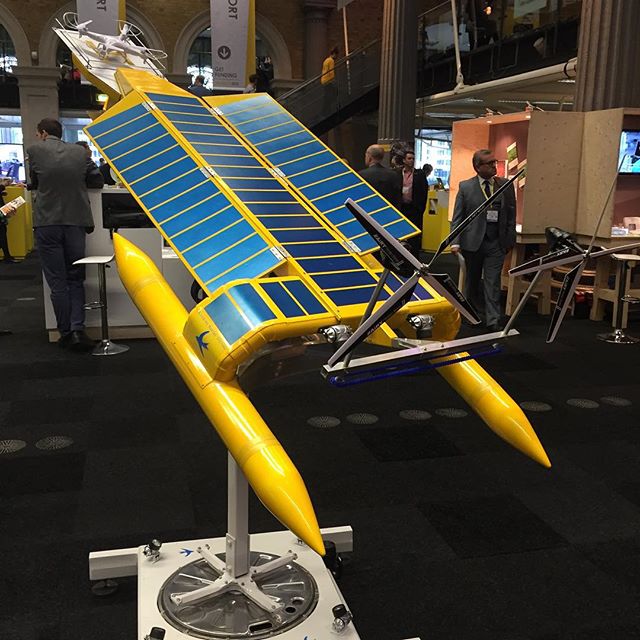

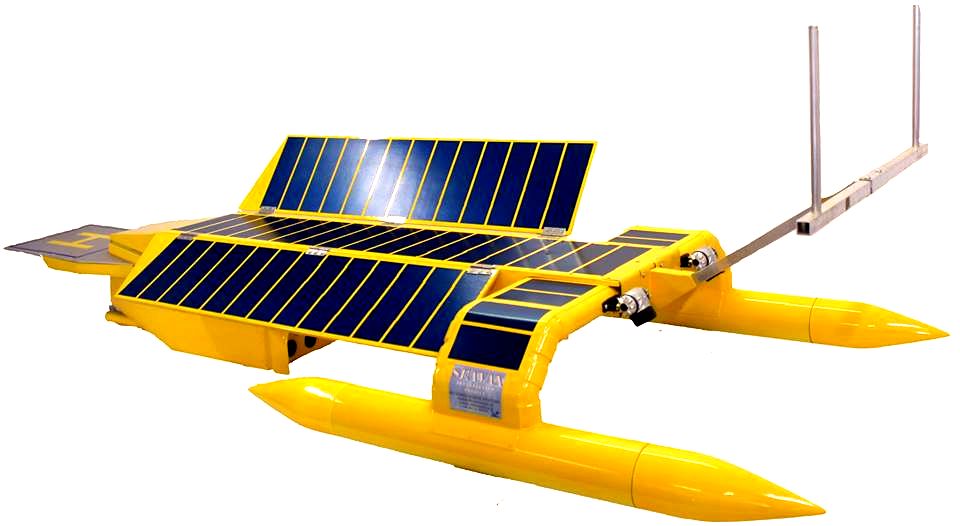

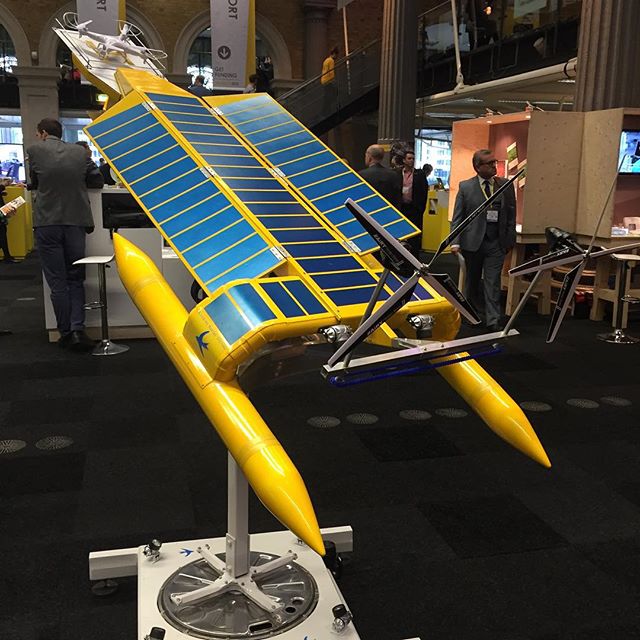

SEAVOLUTION -

Ocean regeneration would help the EU and UN-FAO achieve their blue

growth ambitions,

for which the SeaVax platform,

may have been just the ticket as a robotic ocean workhorse. The proposal

was based on a stable

trimaran configuration design under development in the UK with a view to

international deployment to 2020 - after which the lack of support from

the EU and UK finally forced the project to be shelved (indefinitely).

Though, there is nothing stopping others taking up the gauntlet. A robot

ship uses no diesel fuel to monitor the oceans autonomously (COLREGS

compliant) 24/7 and 365 days a year - only possible with the revolutionary

energy harvesting system.

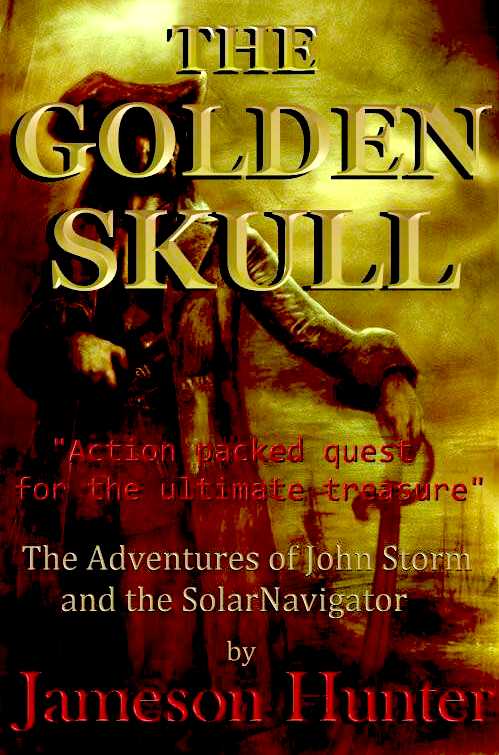

LORD

HUNTINGTON - a prominent member of the British Geographical Society, acquires an ancient parchment on the deathbed of a famous explorer, handed down through

generations, father to son, which contains clues to the location of pirate,

Henry

Morgan's accumulated treasure trove on an Island in the Caribbean, said to be guarded by a macabre human spirit manifesting itself as human skull. More to the point these islands are patrolled by the US and South American navies who are in a cold war situation.

Huntington hires John Storm for his expertise in marine archaeology as a consultant to the expedition and the

Elizabeth Swan, a solar powered ship, for its stealth cloaking ability making the boat invisible to radar.

They find the Island avoiding contact with any of the Bolivarian Republic's (of Venezuela) warships which might arouse curiosities but despite all efforts to keep the reason for the expedition a secret, the word is leaked out by a one of Huntington's arch rivals to a corrupt naval officer, who engages a cutthroat gang of mercenaries to steal the treasure and glory for himself.

The treacherous rival gang soon invades the Island intent on getting the treasure for themselves, having first sabotaged the

Elizabeth Swan .......... or so they thought ....

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC - AEGEAN

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BAY BENGAL - BAY

BISCAY - BERING

- BLACK - CARIBBEAN - CORAL

- EAST CHINA - ENGLISH

CH -

FINLAND - GOC

- GULF GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO - GULF THAILAND - GULF

TONKIN - INDIAN -

IONIAN

- IOC

-

IRC

- IRISH

- MEDITERRANEAN - NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC - PERSIAN

GULF

SEA JAPAN

- STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - RED SEA

- SARGASSO

- SEA

LEVEL RISE - SOUTHERN

OCEAN - TYRRHENIAN

- UNCLOS

- UNEP

WOC

- WWF

AMAZON

- BURIGANGA - CITARUM -

CONGO -

CUYAHOGA

-

GANGES - IRTYSH

- JORDAN -

LENA -

MANTANZA-RIACHUELO

MARILAO

- MEKONG -

MISSISSIPPI -

NIGER -

NILE -

PARANA -

PASIG -

SARNO - THAMES

- YAMUNA -

YANGTZE -

YELLOW -

ZHUJIANG

|