|

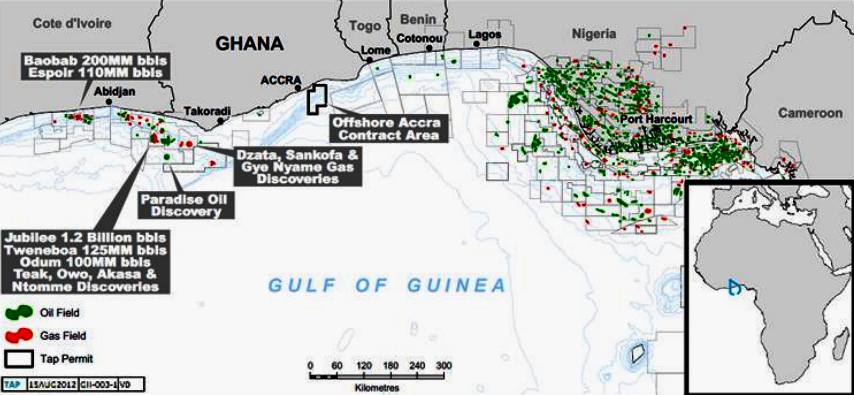

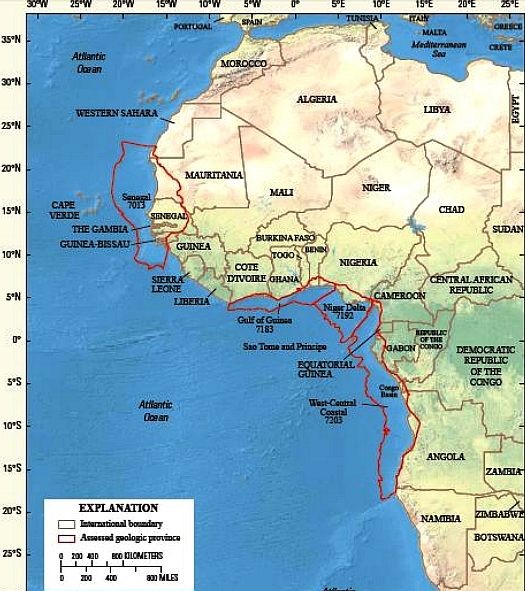

Map

of the Gulf of Guinea

The Gulf of Guinea runs from Guinea on Africa’s northwestern tip to Angola in the south and includes Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Cameroon.

We have included Equatorial Guinea in this article because of the need for

close to states to tackle pollution as part of a coordinated effort - in

the interests of those African nations.

A stretch of West Africa’s coast spanning more than a dozen countries, the Gulf of Guinea is a growing source of oil, cocoa and metals to world markets.

But rising rates of piracy, drug smuggling, and political uncertainty in an area ravaged by civil wars and coups have made it a challenging destination for investors seeking to benefit from the massive resources.

Gulf of Guinea nations produce more than 3 million barrels of oil per day — about 4 percent of the global total — mostly for European and American markets, with the bulk coming from

OPEC member Nigeria (2.2 million bpd). Smaller producers include Equatorial Guinea (300,000 bpd), Congo Republic (340,000 bpd), Gabon (230,000 bpd), Cameroon (66,000 bpd) and Ivory Coast (40,000 bpd).

GULF

OF GUINEA GEOGRAPHY

The Gulf of Guinea is the

north-easternmost part of the tropical Atlantic Ocean between Cape Lopez in Gabon, north and west to Cape Three Points in Western region Ghana. The intersection of the Equator and Prime Meridian (zero degrees latitude and longitude) is in the gulf.

Among the many rivers that drain into the Gulf of Guinea are the Niger and the Volta. The coastline on the gulf includes the Bight of Benin and the Bight of Bonny.

The Niger River in particular deposited organic sediments out to sea over millions of years which became crude oil. The Gulf of Guinea region, along with the Congo River delta and Angola further south, are expected to provide around a quarter of the United States'

oil imports by 2015. This region is now regarded as one of the world's top oil and gas exploration hotspots.

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the southwest extent of the Gulf of Guinea as "A line running Southeastward from Cape Three Points in Western region Ghana (4.744°N 2.089°W) to Cape Lopez in Gabon (0°38′S 8°42′E)"

EQUATORIAL

GUINEA - GEOGRAPHY & CLIMATE

Equatorial Guinea is in west central Africa. The country consists of a mainland territory, Río Muni, which is bordered by Cameroon to the north and Gabon to the east and south, and five small islands, Bioko, Corisco, Annobón, Elobey Chico (Small Elobey), and Elobey Grande (Great Elobey). Bioko, the site of the capital, Malabo, lies about 40 kilometers (25 mi) off the coast of Cameroon. Annobón Island is about 350 kilometers (220 mi) west-south-west of Cape Lopez in Gabon. Corisco and the two Elobey islands are in Corisco Bay, on the border of Río Muni and Gabon.

Equatorial Guinea lies between latitudes 4°N and 2°S, and longitudes 5° and 12°E. Despite its name, no part of the country's territory lies on the equator—it is in the northern hemisphere, except for the insular Annobón Province, which is about 155 km south of the equator.

Equatorial Guinea has a tropical climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. From June to August, Río Muni is dry and Bioko wet; from December to February, the reverse occurs. In between there is gradual transition. Rain or mist occurs daily on Annobón, where a cloudless day has never been registered. The temperature at Malabo, Bioko, ranges from 16 °C (61 °F) to 33 °C (91 °F), though on the southern Moka Plateau normal high temperatures are only 21 °C (70 °F). In Río Muni, the average temperature is about 27 °C (81 °F). Annual rainfall varies from 1,930 mm (76 in) at Malabo to 10,920 mm (430 in) at Ureka, Bioko, but Río Muni is somewhat drier.

The

Bay of Venus, Malabo, Gulf of Guinea

EQUATORIAL

GUINEA - ECONOMY

Pre-independence Equatorial Guinea exported cocoa, coffee and

timber mostly to its colonial ruler, Spain, but also to Germany and the UK. On 1 January 1985, the country became the first non-Francophone African member of the franc zone, adopting the CFA as its currency. The national currency, the ekwele, was previously linked to the Spanish peseta.

The discovery of large oil reserves in 1996 and its subsequent exploitation have contributed to a dramatic increase in government revenue. As of 2004, Equatorial Guinea is the third-largest oil producer in Sub-Saharan Africa. Its oil production has risen to 360,000 barrels per day (57,000 m3/d), up from 220,000 only two years earlier.

Forestry, farming, and fishing are also major components of GDP. Subsistence farming predominates. The deterioration of the rural economy under successive brutal regimes has diminished any potential for agriculture-led growth.

In July 2004, the United States Senate published an investigation into Riggs Bank, a Washington-based bank into which most of Equatorial Guinea's oil revenues were paid until recently, and which also banked for Chile's Augusto Pinochet. The Senate report, as to Equatorial Guinea, showed that at least $35 million were siphoned off by Obiang, his family and senior officials of his regime. The president has denied any wrongdoing. While Riggs Bank in February 2005 paid $9 million as restitution for its banking for Chile's Augusto Pinochet, no restitution was made with regard to Equatorial Guinea, as reported in detail in an Anti-Money Laundering Report from Inner City Press.

Equatorial Guinea is a member of the Organization for the Harmonization of Business Law in Africa (OHADA). Equatorial Guinea tried to become validated as an Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)–compliant country, working toward transparency in reporting of oil revenues and the prudent use of natural resource wealth. The country was one of thirty candidate countries and obtained candidate status on 22 February 2008. It was then required to meet a number of obligations to do so, including committing to working with civil society and companies on EITI implementation, appointing a senior individual to lead on EITI implementation, and publishing a fully costed Work Plan with measurable targets, a timetable for implementation and an assessment of capacity constraints. However, when Equatorial Guinea applied to extend the deadline for completing EITI validation, the EITI Board did not agree to the extension.

According to the World Bank, Equatorial Guinea has the highest GNI (Gross National Income) per capita of any other Sub-Saharan country. It is 83 times larger than the GNI per capita of Burundi which is the poorest country.

A 2004 US Senate investigation into the Washington-based Riggs Bank found that President Obiang's family had received huge payments from US oil companies such as

Exxon Mobil and Amerada Hess.

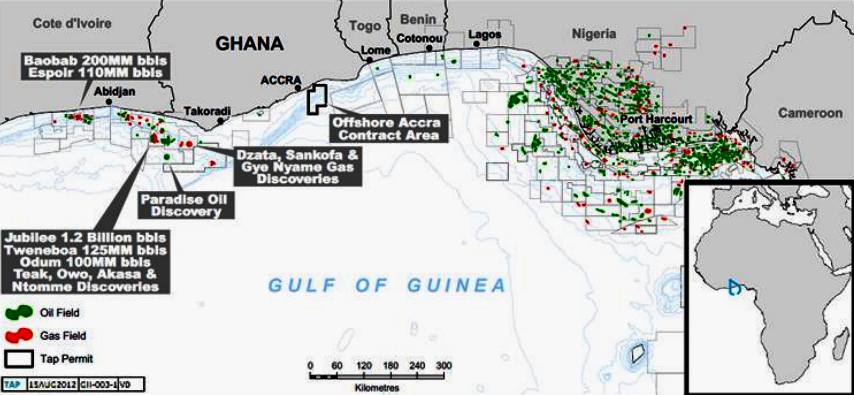

ACCRA

JOINT VENTURE - JV partner Tap Oil has announced the award by the Accra Joint Venture of the Drilling Rig Services contract for the drilling of the Starfish Prospect to Stena Drilling. The Starfish-1 well will be drilled by the Stena DrillMAX, Dual Derrick Drillship which has recently drilled eight efficient and successful wells in Ghana. Stena Drilling has extensive experience in Ghana and is providing this latest generation rig at competitive day rates in conjunction with an existing West African drilling program, thereby minimising mobilisation and demobilisation charges for the Accra Joint Venture.

Starfish-1 is a wildcat well expected to spud in June 2013. The well will target a large, fan complex in the deep water of eastern Ghana, interpreted to be potentially comparable to the Jubilee field in western Ghana. Tap estimates that the well will target prospective resources potentially in the order of half a billion barrels (431 mmbbls (P50); 665mmbbls (PMean)).

The Offshore Accra Contract Area is located in an emerging oil province on the West Africa Transform Margin, along the northern Gulf of Guinea. A number of discoveries have been made in a variety of comparable geological settings along this margin. In 2007, the Jubilee field (one of the largest oil discoveries in the world in 2007) was discovered by Kosmos Energy and Tullow Oil, establishing a new deepwater play offshore Ghana. Subsequent discoveries in Ghana (Tweneboa, Odum, Owo, Teak, Akasa, Dzata, Sankofa, Gye Nyame and Paradise) and in the Liberian Basin (Venus and Mercury) have further demonstrated the potential that exists along the whole margin.

The Accra Joint Venture, with participating interests, comprises: Ophir Ghana (Accra) (Operator) 20%; Afex Oil (Ghana) 20%; Vitol Upstream (Accra) 30%; Rialto Energy (Ghana)* 12.5%; Tap Oil (Ghana) 17.5%; Ghana National Petroleum Corp** 10% carried.

* The entry of Rialto Energy (Ghana) remains conditional on it providing a letter of credit in respect of its participating interest share of the approved work program and budget for the current Exploration Period.

**Carried by the other parties in proportion to their Participating interest. GNPC has the option of increasing its interest in the event of a commercial discovery.

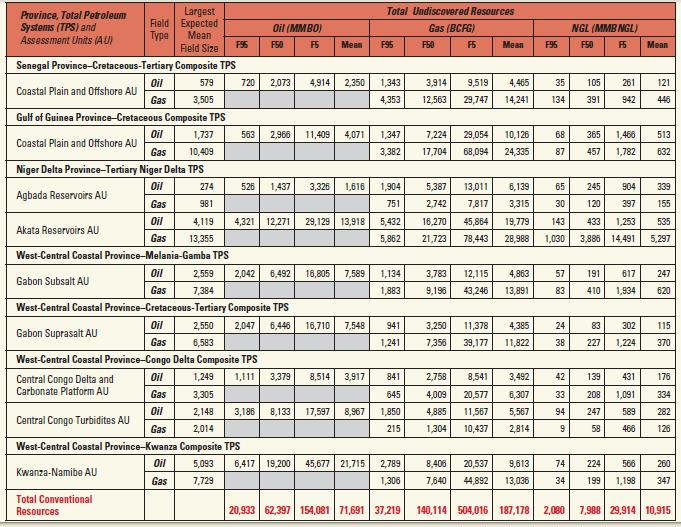

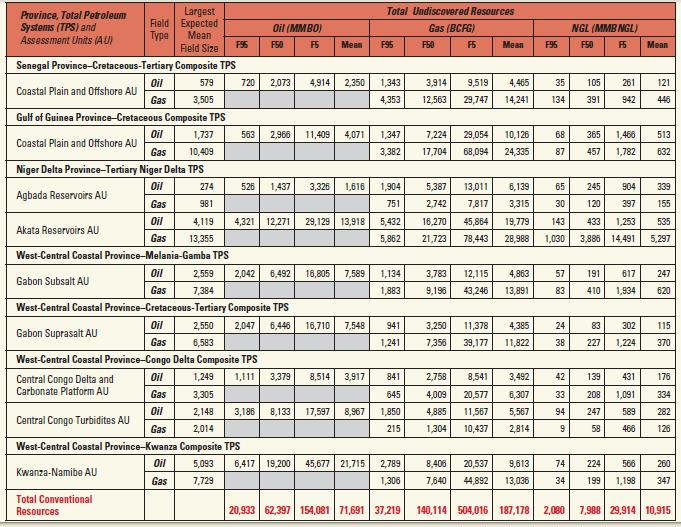

OIL

TABLE - West Africa Provinces assessment results for undiscovered, technically recoverable oil, gas, and natural gas liquids.

Largest expected mean field size in million barrels of oil and billion cubic feet of gas; MMBO, million barrels of oil. BCFG, billion cubic feet of gas. MMBNGL, million barrels of natural gas liquids. Results shown are fully risked estimates. For gas accumulations, all liquids are included as natural gas liquids (NGL). Undiscovered gas resources are the sum of nonassociated and associated gas. F95 represents a 95 percent chance of at least the amount tabulated; other fractiles are defined similarly. AU, assessment unit; AU probability is the chance of at least one accumulation of minimum size within the AU. NGL, natural gas liquids. TPS, total petroleum system. Gray shading indicates not applicable.

PLASTIC POLLUTION -

Marine Pollution Bulletin, Volume 44, Issue 7, July 2002 Abstract:

Environmental pollution in the Gulf of Guinea (GOG) coastal zone has caused eutrophication and oxygen depletion in the lagoon systems, particularly around the urban centres, resulting in decreased

fish (reproduction) levels and waterborne diseases. A pollution sources assessment was undertaken by six countries in the region as a first step in defining a region-wide Environmental Management Plan. Results show that households produce 90% of solid waste. Industry, however, is responsible for substantial amounts of hazardous waste, specifically the Nigerian petroleum industry. The latter is also responsible for the spilling of large amounts of oil. BOD load from industrial effluents is slightly larger than domestic loads in the industrialised coastal zone. Wastewater treatment systems are either absent or inadequate. Apart from large-scale gas flaring in Nigeria, air pollution, in terms of COx, HC,NOx and SO2 emissions, is contributed mainly by traffic. Particulates, originate mainly from industries and domestic biomass burning. (... "the enormous bulk of solid waste produced daily by households and industries in the coastal zone forms a serious threat to the environment"...)

Over 80% of marine pollution comes from land-based activities.

It must then be that to preserve fish stocks and the health of nations

bordering the Gulf of Guinea, that responsible waste management is

installed. From plastic bags to pesticides - most of the waste we produce on land eventually reaches the oceans, either through deliberate dumping or from run-off through drains and rivers.

As a minister in this region you may well be looking for a solution that

will not cost the earth.

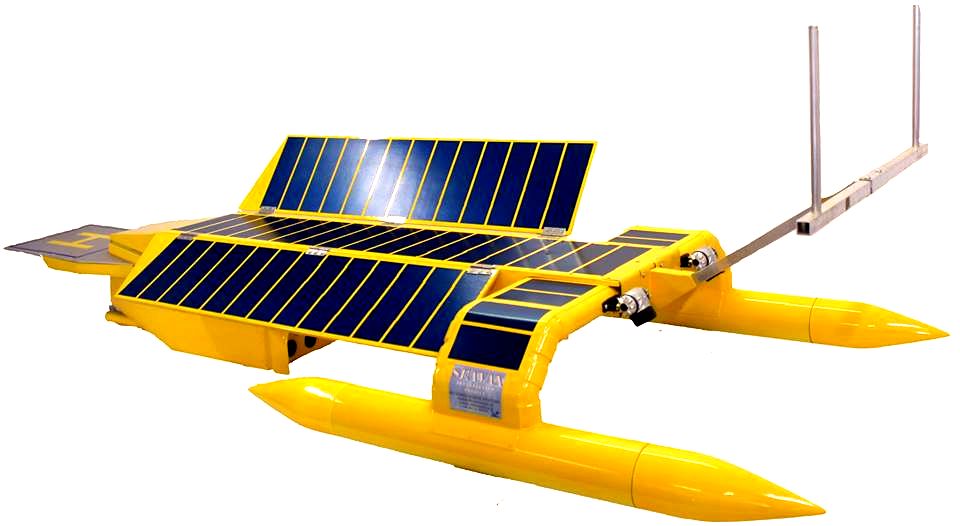

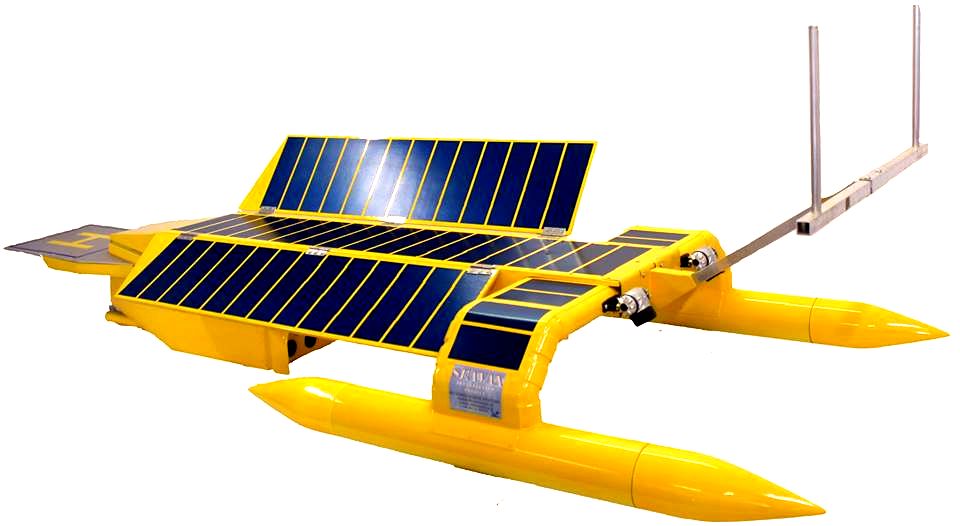

UNDER

DEVELOPMENT - Presently under development, the SeaVax concept

potentially offers a solution to ocean pollution. The speed that this

project proceeds is entirely dependent on the level of support and

interest that may be expressed by governments who are responsible for

their patch and/or organizations that are looking to coordinate such

efforts.

BMS

LTD - is the only company in the world that is seriously looking

to produce such a vessel. The SeaVax concept is designed to deal with

ocean plastic waste as the baseline upon which to offer additional facilities

such as a built in oil spillage collection module.

PROPOSED

SEVAX

POLLUTION SOLUTION

One

possible scenario for the Gulf of Guinea, is for the attendees of the

Large Marine Eco Project (LMEP) to reform, or if that is not practical to

assemble a fresh body of representatives, perhaps with input from the

local member of the Global Ocean Commission.

Once

formed, such a committee, referred to herein as the Gulf of Guinea Marine

Management Coalition (GMC) could either look at the feasibility of

securing a fleet of SeaVax ocean cleaners, or look at that scenario by comparison

with alternative solutions.

The

suggestion is that the GMC might reflect on the potential for fines for

oil spillages and the contingency for such events, taking into

consideration the corporate responsibility of oil producers and the duty

of care that the Members of the Coalition owe, firstly to their population

- and secondly, to the international community - to help tackle declining

fish stocks.

In

the event of future oil spills consideration is sure to be given when it

comes to levying fines. While a fleet of solar and wind powered robots is

waiting for the inevitable oils spills, they can earn their keep by

patrolling the coast continuously for plastic and other debris that is

coming from the land.

Such

an endeavor will set a fine example to other nations who, at the moment, are

doing nothing like this.

OBIAGELI

(OBY) EZEKWESILI - is a former Vice President of the World Bank for Africa, a former Nigerian Education Minister and co-founder of Transparency International.

Dr Ezekwesili holds a Master’s degree in International Law and Diplomacy from the University of Lagos, and a Master’s in Public Administration from the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University. She was awarded an honorary Doctor of Science degree by the University of Agriculture in Abeokuta in 2012.

A chartered accountant by profession, ‘Oby’ Ezekwesili first served the Nigerian government as Head of the Budget Monitoring and Price Intelligence Unit, where she led reforms to public procurement. She was appointed Minister of Solid Minerals in 2005 and chaired the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. In 2006 she became Minister of Education, until taking up her World Bank post in 2007. Prior to working for the Government of Nigeria, Dr Ezekwesili was at the Center for International Development at Harvard University. Having co-founded the anti-corruption organisation Transparency International, she directed its work in Africa. She is also a Senior Economic Advisor to Open Society, which aims to build vibrant and tolerant societies with democratically accountable governments.

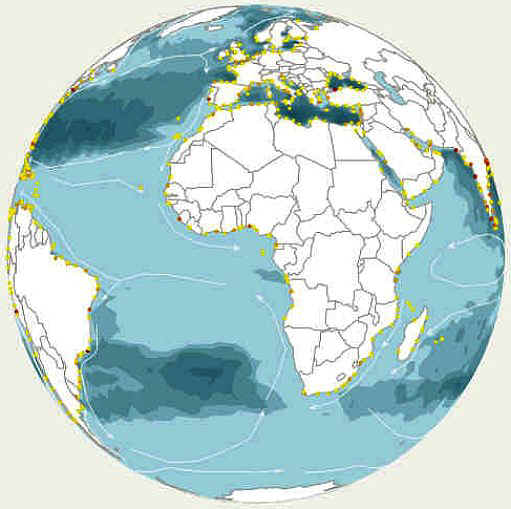

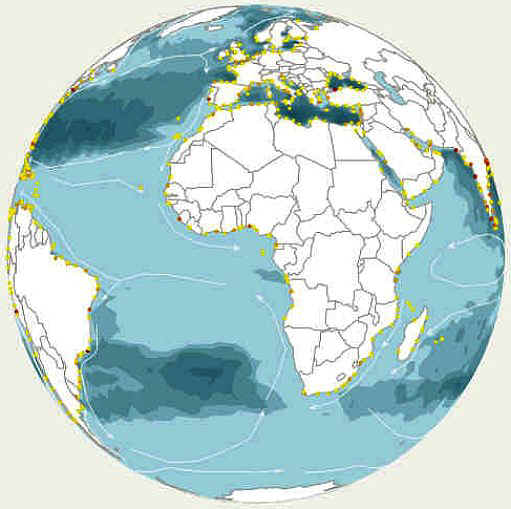

THE

GLOBAL

OCEAN COMMISSIONERS

- Your representative for the GOC is shown on this map of the world showing the location of the

Commissioners. ‘Oby’ Ezekwesili is the most appropriate contact for

West Africa.

INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION (Of UNESCO)

JOINT IOC XJNIDO WORKSHOP ON MARINE DEBRIS/WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR THE GULF OF GUINEA

- 18 June 1999

Abidjan, Cote d’hoire, 19-21 April 1999 the management process and audits

the results. The challenge is to create a competent and trusted institution

to foster a successful, long-term stewardship process.

To combat marine debris, the introduction of co-management as a capacity building strategy is a necessity for the countries of the Gulf of Guinea.

Co-management is defined as a joint management arrangement, an institutional

arrangement in which responsibility for resource management, conservation and/or economic development is shared between governments and user

groups.

Co-management provides opportunity for government to refocus from micro management to macro

frameworks. Stakeholders can assume responsibilities for management decisions while government sets overall

objectives.

This

was a good start to engaging those responsible for managing the area, but

what happened?

SECRETARIAT

Dr Jacques ABE

Centre de Recherches Oceanologiques

Large Marine Ecosystem Project for the Gulf of Guinea

BP V 18 ABIDJAN - Cote d’lvoire

Tel: 35-50-14/35-58-80/08-58-00

Fax: 35- 1 l-55125-73-69

E-mail: Abe@cro.orstom.ci

E-mail: gog-lme@afiicaonline.co.ci

Mr Julian BARBIERE

Programme Specialist

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

UNESCO

I rue Miollis

75735 Paris Cedex 15

Tel: 3301 4568 4045

Fax: 3301 4568 5812

E-mail: j.barbiere@unesco.org

AFRICA'S LEAKING WOUND - OIL BASED PIRACY

ACROSS THE GULF, MARCH 2013

Like blood from a leaking wound, the piracy that is spreading westward from Nigeria has now reached the Ivory Coast, 400 miles from its origins on the inland and coastal waters of the Niger Delta. There, and on the waters more than 100 miles off these countries’ coasts, acts of depredation against ships and fixed oil installations have resulted in far greater financial losses and had a far wider economic impact that any piracy seen so far anywhere else in the world.

International concern has been growing for some time. The U.N. Security Council (UNSC), having expressed its alarm about piracy in the Gulf of Guinea in August 2011, passed resolution 2018 two months later, re-emphasizing that concern and urging regional states to take effective action against the pirates’ backers and financiers. 1 The Economic Community of West and Central Africa and the Gulf of Guinea Commission assessed that piracy was “rapidly spreading around the region and increasingly dovetailing into oil bunkering, robbery at sea, hostage-taking, human and drug trafficking, terrorism and corruption,” while resource shortfalls and inadequate legal frameworks meant that piracy suspects were being released.

This despite the fact that the International Maritime Organization had been working with the Maritime Organization of West and Central Africa for nearly four years to develop a coast-guard network and improve regional maritime security cooperation.

Are they right to be worried? Context matters, and West African piracy cannot be viewed separately from the larger issues of Salafist violence spreading from the interior, consequent religious and intercommunal violence in the more populous areas closer to the coast, endemic corruption, links between elites and criminals, massive income inequality, the prospect of state failure, and, standing behind all those, the insatiable need for oil and gas that fuels the competitive behavior of states, international oil companies, and domestic elites.

The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) reports that Gulf of Guinea piracy attacks were generally up in 2012 over 2011, the only decline occurring off Benin. In terms of actual numbers the IMB reports 58 incidents for the region as a whole in 2012 compared with 51 in 2008 (the previous high point) and 44 in 2011.

That compares with 75 incidents off Somalia in 2012 versus 237 in 2011. However, the reliability of piracy statistics has always been questionable, none more so than for Nigeria, where some commentators have suggested that rates of under-reporting may be closer to 80 percent than the 50 percent that has been the rule of thumb elsewhere.

FESTERING SOCIAL UNREST

It is the value of what is being taken that has changed the dynamic in the Gulf of Guinea. Starting in 2010, pirates began to target product tankers, siphoning off tens of millions of dollars worth of refined oil then selling it back into Nigeria and other regional markets. The use of “mother ships” has enabled gangs to capture targets farther afield using levels of violence that differentiate them sharply from pirates off Somalia and in the Malacca Strait. Kidnap-for-ransom of foreign oil workers from supply vessels and isolated oil platforms has continued, although “hardening” measures have made this increasingly difficult. Nigeria’s security measures have also intensified, in particular Operation Pulo Shield, a campaign led by the controversial Joint Task Force to hit oil thieves and illegal refiners, which has chalked up impressive successes over the past year, although the number of cases actually prosecuted are worryingly few.

Those efforts, however, rest on shaky foundations. Unrest in the Niger Delta arises from the well-grounded conviction among the region’s minority tribes that oil companies colluded with greedy Nigerian politicians over decades to extract billions of dollars of oil for their own benefit at the expense of local habitat and the livelihoods it supported.

The main grievances are poverty, high youth unemployment, hiring practices that discriminate against locals and between local tribes, and the manipulation of government power by powerful ethnic groups outside the oil-rich Delta region to seize its oil wealth for themselves. The sense of injustice and exploitation that pervade the region has roots in a long struggle by local people for autonomy stretching back generations. The consequent social unrest has a strong criminal dimension. Almost unimaginable quantities of oil have been stolen—more than some African countries actually produce—directly from pipelines, fraudulently removed from storage facilities, and on a much smaller scale from ships at sea. Drawing a simplistic distinction between politically and criminally motivated actions in this conflict, however, fails to take into account the complicity of oil companies and federal and state governments in what amounts to a human and environmental tragedy; such arguments, Nigerian Professor Ukoha Ukiwo says, exhibit “too much economism, too little politics and no history at all.”

NIGERIA'S TWO-PRONGED STRATEGY

The Nigerian government’s response to this unrest and oil theft, which has so often turned to violence, has rested on two pillars: Coercive power, epitomized by the Pulo Shield operation, which over time has grown in intensity, and since 2009, an amnesty program that effectively buys off the militants but has made no coherent effort to address what causes the militancy in the first place.

The effectiveness of the first pillar risks being undermined by growing Islamist violence in the Muslim north. This has spread into the country’s more populous middle belt, where it has exploited longstanding intercommunal tensions. That violence has been perpetrated mainly by the militant jihadist organization Boko Haram and its various splinter groups, such as Ansaru. They have coordinated attacks with al Qaeda in the Islamic Magreb (AQIM), which took effective control of large swaths of Mali, was behind the January 2013 assault on the In Amenas natural gas facility in Algeria, and according to African affairs analyst J. Peter Pham has “never hidden its ambition to bring in Nigerian Islamists in order to exploit tensions between Nigerian Muslims and Christians.” 9 Fighting them has distorted government expenditures—some 20 percent now goes to security—and drawn forces away from the Niger Delta including, reportedly, U.S.-trained boat crews, while denying the navy the funds needed to maintain its vessels and surveillance aircraft.

The second pillar—amnesty—was a bold move that induced militants to hand in weapons for cash payments and enroll in rehabilitation and training programs. About 26,000 militants from various organizations eventually surrendered in return for a monthly stipend worth three times the minimum wage. The continuing high global oil price has meant that, to date, payments have been maintained at the promised level—including much higher payments to ex-leaders so they’ll do whatever is necessary to keep their former followers in line. Keeping ex-leaders on-side has included granting at least one notorious militant, Mujahid Dokubo-Asari, a $9 million contract to protect the oil installations he spent most of his career attacking.

Critics point out that the program is fiscally unsustainable, with more money going to ex-militants than to the health service; for the program’s defenders, however, keeping the oil and its revenue flowing is justification enough.

The amnesty’s more serious flaw, however, has been the assumption that militancy was simply an outbreak of “large-scale organized crime” in which “once legitimate grievances [had] been abandoned to outright predation.” 13 It consequently failed to address the fact that delta tribal groups believed they were supporting a corrupt political class and had not benefitted from the half-trillion dollars the oil industry has paid Nigeria since 1970. Peace, in other words, was bought, not built. The risk in that approach was always that some fighters would return to the region’s creeks and begin the cycle of violence all over again. The formation of self-styled “third phase” militant groups seems to suggest that this is what is happening. Another expression has been the growth of piracy: militancy has moved offshore.

CORRUPTION ENTRENCHED EPIDEMIC

The root of the problem, and the principal obstacle to resolving the social and ethnic unrest in the Niger Delta, is corruption at all levels of government. Inequalities of income feed the problem: Nigeria is the continent’s second largest economy yet had a poverty rate of 70 percent in 2007, while at the same time billions of dollars of oil revenue disappeared into the overseas bank accounts of corrupt politicians and officials. Large sections of Nigerian society do not trust their own government. Crime is a national epidemic; one that the police

- lacking adequate pay, training, or numbers - seemingly aid and abet through their own predatory behavior. The enormous sums involved in oil theft

- known as illegal bunkering - attracted the interest of military figures early on who demanded payment to look the other way.

Once the country returned to civilian rule in 1999, oil revenue was decentralized, and so was corruption. By 2009, for example, the income of Rivers State alone was, at $2.9 billion, greater than that of several African countries. With more money in their hands, state governors saw their wealth and patronage power increase immeasurably. Politicians quickly recognized the advantages of associating with the well-funded and well-armed oil bunkering gangs, although the gangs’ political allegiance was never strong.

The best-known and most successful of the numerous militant organizations that sprang up was MEND, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta. Formed in late 2005 by a collection of pre-existing groups, it essentially disbanded, at least in its original manifestation, following the announcement of the 2009 amnesty.

It was never a unified entity. Some judged it to have been a primarily criminal organization despite its very public claims to the contrary. Others, while not denying the criminal element, pointed to the federal government’s reluctance to provide security in situations that were not directly oil-related. Such selective application of law enforcement, along with other social pressures, had led each tribe to form armed groups to defend its interests; by the early 2000s those very groups had begun to drift into criminality, particularly illegal bunkering.

Rising oil prices have ensured that oil theft remains highly profitable. Leaked U.S. diplomatic cables suggest those linked to shady deals have included the wife of a former president and unnamed high-ranking politicians in the nation’s capital, Abuja. Unconfirmed reports assert that Lebanese nationals possibly funding the terrorist groups Hamas and Hezbollah, the Russian mafia, and drug cartels may also be involved. None of that theft would be possible on land or at sea without the complicity of many in Nigeria’s political elite, the national oil company, and the military.

THE DRUG TRADE & EXTREMISTS

Organized crime is thriving across the whole Gulf of Guinea region. Narcotics smuggling is the principal driver: drugs shipped across the Atlantic by air and sea

- increasingly by submarine

- are landed along the West African coast then smuggled into Europe by air or by land across the Sahara. It may yet be inappropriate to draw parallels between West Africa and Mexico or Central America but that could change. The great worry is that more states may go the way of Guinea-Bissau, where drug cartels already wield significant influence.

The extent to which drug gangs are involved in oil theft is unclear. With crime, however, comes corruption. As William Hughes, the ex-head of the United Kingdom’s Serious and Organized Crime Agency, told a conference in 2009, it is “very difficult to deal with the indigenous law enforcement [agencies of West African governments] because they’re all controlled by ministers and other government officials who are all suspect, if not actively involved in [crime].”

Those states may be a long way from failing. Nonetheless, they are necessarily weaker than states where the government’s legitimacy is acknowledged, which in a West African context means they would be better placed to withstand social unrest arising from ethnic and religious differences, economic inequality, and natural-resource competition. The divide between northern Muslims and southern

Christians, which has turned violent in Nigeria but is still peaceful elsewhere, nonetheless exists all the way from Nigeria to Senegal, and may be similarly open to extremist exploitation.

EXTERNAL INFLUENCES & FUTURE

Countering those actors, and pirates, draws in external powers. The United States initiated the first

Africa Partnership Station mission along the West African coast in 2007.

Increased Islamist activity in Mali has prompted deeper U.S. engagement in the region, including building a drone base in Niger.

France has also been very active. In 2011, well before the recent intervention against al Qaeda elements in Mali, the French announced a $10 million regional maritime-security mission. In January of this year the European Union announced a €4.5 million ($6.1 million) regional

anti-piracy initiative.

Those traditional relationships have now been complicated by growing investments from Russia and China, particularly the latter—Africa’s largest trading partner.

At-risk economic investments are often followed by defense involvement. Lagos has been mentioned as the possible location for a Chinese “overseas strategic support base” for distant-water naval operations, supplementing two other suggested locations. One is in Namibia and the other in Angola, which already is one of China’s principal oil suppliers.

In 2005 the National Intelligence Council predicted that Nigeria would be a failed state by 2020, perhaps reflecting that the discovery of oil does not automatically produce development.

Oil was discovered in Nigeria shortly before independence and since then the country’s GDP per capita and life expectancy have both declined. The current international system that makes international recognition—not internal legitimacy or functionality—the key to state authority works to the benefit of dysfunctional oil producers in the developing world. Enclaves that are valuable to oil consumers—and to the domestic elites who facilitate and benefit from international legitimization—function well enough. They include oil and gas fields, export terminals, oil-related shipping, and offshore infrastructure around which defensive perimeters can be drawn, leaving the space in between relatively unprotected.

Piracy is inseparable from economic and political conditions on land and although the number of incidents may rise or fall, as long as the conditions that favor piracy remain propitious then even the most extensive and sophisticated security regimes will find it difficult to control the problem—particularly if they have to fight other fires as well. Those conditions are in place around the Gulf of Guinea. 31 Recommendations to address these conditions have been made regularly within Nigeria as part of widespread political, economic, and social reform.

Deep-seated social attitudes, such as tolerance of corruption and the perpetuation of subsidies that distort Nigeria’s internal energy market, are major obstacles to change. If Nigeria continues to be beset by political and criminal dislocation, that will continue to have a destabilizing effect on its neighbors. Without meaningful reform all that remains is the language and methods of security.

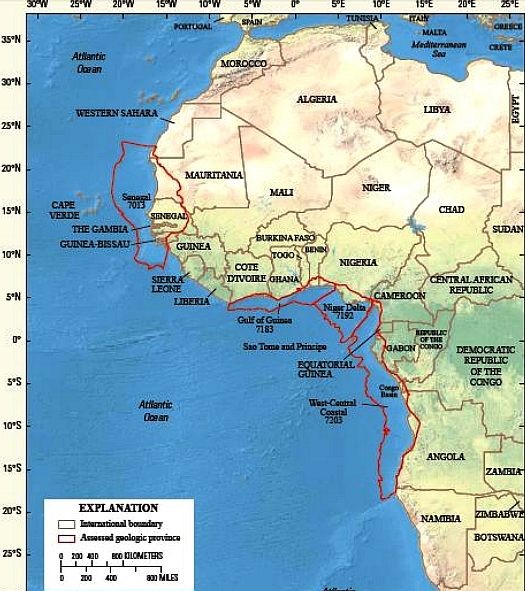

RED

INK - Four geologic provinces located along the northwest and west-central coast of Africa recently were assessed for undiscovered oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids resources as part of the U.S. Geological Survey’s

(USGS) World Oil and Gas Assessment. Using a geology-based assessment methodology, the USGS estimated mean volumes of 71.7 billion barrels of oil, 187.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 10.9 billion barrels of natural gas liquids.

Estimated undiscovered and recoverable oil and natural gas off the coast of Ivory Coast, extending through Ghana, Togo, Benin, and the western edge of Nigeria.: 4,071 MMBO, million barrels of oil, 34,451 BCFG, billion cubic feet of gas, and 1,145 MMBNGL, million barrels of natural gas liquids, for the Coastal Plain and Offshore AU in the Gulf of Guinea Province, outlined in red. This does not include current existing discoveries, or fields already in production. Note that it extends along the entire coast of Ivory Coast.

OIL

SPILL MINI HISTORY

|

Year

|

Rig

Name

|

Rig

Owner

|

Type

|

Damage

/ details

|

|

1955

|

S-44

|

Chevron

Corporation

|

Sub

Recessed pontoons

|

Blowout

and fire. Returned to service.

|

|

1959

|

C.

T. Thornton

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire damage.

|

|

1964

|

C.

P. Baker

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Drill

barge

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico, vessel capsized, 22 killed.

|

|

1965

|

Trion

|

Royal

Dutch Shell

|

Jackup

|

Destroyed

by blowout.

|

|

1965

|

Paguro

|

SNAM

|

Jackup

|

Destroyed

by blowout and fire.

|

|

1968

|

Little

Bob

|

Coral

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire, killed 7.

|

|

1969

|

Wodeco

III

|

Floor

drilling

|

Drilling

barge

|

Blowout

|

|

1969

|

Sedco

135G

|

Sedco

Inc

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

damage

|

|

1969

|

Rimrick

Tidelands

|

ODECO

|

Submersible

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1970

|

Stormdrill

III

|

Storm

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire damage.

|

|

1970

|

Discoverer

III

|

Offshore

Co.

|

Drillship

|

Blowout

(S. China Seas)

|

|

1971

|

Big

John

|

Atwood

Oceanics

|

Drill

barge

|

Blowout

and fire.

|

|

1971

|

Wodeco

II

|

Floor

Drilling

|

Drill

barge

|

Blowout

and fire off Peru, 7 killed.

|

|

1972

|

J.

Storm II

|

Marine

Drilling Co.

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1972

|

M.

G. Hulme

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and capsize in Java Sea.

|

|

1972

|

Rig

20

|

Transworld

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Martaban.

|

|

1973

|

Mariner

I

|

Sante

Fe Drilling

|

Semi-sub

|

Blowout

off Trinidad, 3 killed.

|

|

1975

|

Mariner

II

|

Sante

Fe Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Lost

BOP during blowout.

|

|

1975

|

J.

Storm II

|

Marine

Drilling Co.

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico.

|

|

1976

|

Petrobras

III

|

Petrobras

|

Jackup

|

No

info.

|

|

1976

|

W.

D. Kent

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Damage

while drilling relief well.

|

|

1977

|

Maersk

Explorer

|

Maersk

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire in North Sea

|

|

1977

|

Ekofisk

Bravo

|

Phillips

Petroleum

|

Platform

|

Blowout

during well workover.

|

|

1978

|

Scan

Bay

|

Scan

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire in the Persion Gulf.

|

|

1979

|

Salenergy

II

|

Salen

Offshore

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1979

|

Sedco

135F

|

Sedco

Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

and fire in Bay of Campeche Ixtoc

I well.

|

|

1980

|

Sedco

135G

|

Sedco

Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

and fire of Nigeria.

|

|

1980

|

Discoverer

534

|

Offshore

Co.

|

Drillship

|

Gas

escape caught fire.

|

|

1980

|

Ron

Tappmeyer

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Persian Gulf, 5 killed.

|

|

1980

|

Nanhai

II

|

Peoples

Republic of China

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

of Hainan Island.

|

|

1980

|

Maersk

Endurer

|

Maersk

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Red Sea, 2 killed.

|

|

1980

|

Ocean

King

|

ODECO

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire in Gulf of Mexico, 5 killed

|

|

1980

|

Marlin

14

|

Marlin

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1981

|

Penrod

50

|

Penrod

Drilling

|

Submersible

|

Blowout

and fire in Gulf of Mexico.

|

|

1985

|

West

Vanguard

|

Smedvig

|

Semi-submersible

|

Shallow

gas blowout and fire in Norwegian sea, 1 fatality.

|

|

1981

|

Petromar

V

|

Petromar

|

Drillship

|

Gas

blowout and capsize in S. China seas

|

|

1983

|

Bull

Run

|

Atwood

Oceanics

|

Tender

|

Oil

and gas blowout Dubai, 3 fatalities.

|

|

1988

|

Ocean

Odyssey

|

Diamond

Offshore Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Gas

blowout at BOP

and fire in the UK North Sea, 1 killed.

|

|

1988

|

PCE-1

|

Petrobras

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

at Petrobras PCE-1 (Brazil) in April 24. Fire burned for 31

days. No fatalities.

|

|

1989

|

Al

Baz

|

Sante

Fe

|

Jackup

|

Shallow

gas blowout and fire in Nigeria, 5 killed.

|

|

1993

|

M.

Naqib Khalid

|

Naqib

Co.

|

Naqib

Drilling

|

fire

and explosion. Returned to service.

|

|

1993

|

Actinia

|

Transocean

|

Semi-submersible

|

Sub-sea

blowout in Vietnam.

|

|

2001

|

Ensco

51

|

Ensco

|

Jackup

|

Gas

blowout and fire, Gulf of Mexico, no casualties

|

|

2002

|

Arabdrill

19

|

Arabian

Drilling Co.

|

Jackup

|

Structural

collapse, blowout, fire and sinking.

|

|

2004

|

Adriatic

IV

|

Global

Sante Fe

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire at Temsah platform, Mediterranean Sea

|

|

2007

|

Usumacinta

|

PEMEX

|

Jackup

|

Storm

forced rig to move, causing well blowout on Kab

101 platform, 22 killed

|

|

2009

|

West

Atlas / Montara

|

Seadrill

|

Jackup

/ Platform

|

Blowout

and fire on rig and platform in Australia.

|

|

2010

|

Deepwater

Horizon

|

Transocean

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

and fire on the rig, subsea well blowout, killed 11 in

explosion.

|

|

2010

|

Vermilion

Block 380

|

Mariner

Energy

|

Platform

|

Blowout

and fire, 13 survivors, 1 injured.

|

|

2012

|

KS

Endeavour

|

KS

Energy Services

|

Jack-Up

|

Blowout

and fire on the rig, collapsed, killed 2 in explosion.

|

|

GUSHERS

- WELL BLOWOUTS

Gushers were an icon of oil exploration during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During that era, the simple drilling techniques such as cable-tool drilling and the lack of blowout preventers meant that drillers could not control high-pressure reservoirs. When these high pressure zones were breached, the hydrocarbon fluids would travel up the well at a high rate, forcing out the drill string and creating a gusher. A well which began as a gusher was said to have "blown in": for instance, the Lakeview Gusher blew in in 1910. These uncapped wells could produce large amounts of oil, often shooting 200 feet (60 m) or higher into the air. A blowout primarily composed of

natural gas was known as a gas gusher.

Despite being symbols of new-found wealth, gushers were dangerous and wasteful. They killed workmen involved in drilling, destroyed equipment, and coated the landscape with thousands of barrels of oil; additionally, the explosive concussion released by the well when it pierces an oil/gas reservoir has been responsible for a number of oilmen losing their hearing entirely; standing too near to the drilling rig at the moment it drills into the oil reservoir is extremely hazardous. The impact on wildlife is very hard to quantify, but can only be estimated to be mild in the most optimistic models—realistically, the ecological impact is estimated by scientists across the ideological spectrum to be severe, profound, and lasting.

To complicate matters further, the free flowing oil was—and is—in danger of igniting. One dramatic account of a blowout and fire reads,

"With a roar like a hundred express trains racing across the countryside, the well blew out, spewing oil in all directions. The derrick simply evaporated. Casings wilted like lettuce out of water, as heavy machinery writhed and twisted into grotesque shapes in the blazing inferno."

The development of rotary drilling techniques where the density of the drilling fluid is sufficient to overcome the downhole pressure of a newly penetrated zone meant that gushers became avoidable. If however the fluid density was not adequate or fluids were lost to the formation, then there was still a significant risk of a well blowout.

In 1924 the first successful blowout preventer was brought to market. The BOP valve affixed to the wellhead could be closed in the event of drilling into a high pressure zone, and the well fluids contained. Well control techniques could be used to regain control of the well. As the technology developed, blowout preventers became standard equipment, and gushers became a thing of the past.

In the modern petroleum industry, uncontrollable wells became known as blowouts and are comparatively rare. There has been significant improvement in technology, well control techniques, and personnel training which has helped to prevent their occurring. From 1976 to 1981, 21 blowout reports are available.

NOTABLE OIL GUSHERS

1. Although it didn't actually happen when drilling for oil, an attempt in 1815 to drill for salt produced the earliest known oil gusher. Joseph Eichar and his team were digging for salt west of the town of Wooster, Ohio, along Killbuck Creek, when they struck oil. In a written retelling by Eichar's daughter, Eleanor, the strike produced "a spontaneous outburst, which shot up high as the tops of the highest trees!"

2. The Shaw Gusher in Oil Springs, Ontario, was North America's (and possibly the world's) first oil gusher when actually drilling for oil. On January 16, 1862, it shot oil from over 60 metres (200 ft) below ground to above the treetops at a rate of 3,000 barrels (480 m3) per day, triggering the oil boom in Lambton County.

3. Lucas Gusher at Spindletop in Beaumont, Texas in 1901 flowed at 100,000 barrels (16,000 m3) per day at its peak, but soon slowed and was capped within nine days. The well tripled U.S. oil production overnight and marked the start of the Texas oil industry.

4. Masjed Soleiman, Iran in 1908 marked the first major oil strike recorded in the Middle East.

5. Dos Bocas in the State of Veracruz, Mexico, was a famous Mexican blowout that formed a large crater, and leaked oil from the main reservoir for many years, even after Pemex nationalized the Mexican oil industry in March 1938.

6. Lakeview Gusher on the Midway-Sunset Oil Field in Kern County, California of 1910 is believed to be the largest-ever U.S. gusher. At its peak, more than 100,000 barrels (16,000 m3) of oil per day flowed out, reaching as high as 200 feet (60 m) in the air. It remained uncapped for 18 months, spilling over 9 million barrels (1,400,000 m3) of oil, less than half of which was recovered.

7. A short-lived gusher at Alamitos #1 in Signal Hill, California in 1921 marked the discovery of the Long Beach Oil Field, one of the most productive oil fields in the world.

8. The Barroso 2 well in Cabimas, Venezuela in December 1922 flowed at around 100,000 barrels (16,000 m3) per day for nine days, plus a large amount of natural gas.

9. Baba Gurgur near Kirkuk, Iraq, an oilfield known since antiquity, erupted at a rate of 95,000 barrels (15,100 m3) a day in 1927.

10. The Wild Mary Sudik gusher in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma in 1930 flowed at a rate of 72,000 barrels (11,400 m3) per day.

11. The Daisy Bradford gusher in 1930 marked the discovery of the East Texas Oil Field, the largest oilfield in the contiguous United States.

12. The largest known 'wildcat' oil gusher blew near Qom, Iran on August 26, 1956. The uncontrolled oil gushed to a height of 52 m (170 ft), at a rate of 120,000 barrels (19,000 m3) per day. The gusher was closed after 90 days' work by Bagher Mostofi and Myron Kinley (USA).

13. One of the most troublesome gushers happened on June 23, 1985 at the well #37 at the Tengiz field in Atyrau, Kazakh SSR, Soviet Union, where the deep, 4209 metre well blew out and the 200-metres high gusher self-ignited two days later. Oil pressure up to 800 atm and high hydrogen sulfide content had led to the gusher being capped only on 27 July 1986 when the well was closed by the shaped charge. The total volume of erupted material measured at 4.3 millions metric tons of oil, 1.7 bn m³ of natural gas, and the burning gusher resulted in 890 tons of various mercaptans and more than 900,000 tons of soot released into atmosphere.

14. The largest underwater blowout in U.S. history occurred on April 20, 2010, in the Gulf of Mexico at the Macondo Prospect oil field. The blowout caused the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon, a mobile offshore drilling platform owned by Transocean and under lease to BP at the time of the blowout. While the exact volume of oil spilled is unknown, as of June 3, 2010, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Flow Rate Technical Group has placed the estimate at between 35,000 to 60,000 barrels (5,600 to 9,500 m3) of crude

oil per day.

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BERING

- CARIBBEAN - CORAL - EAST

CHINA

ENGLISH CH

-

GOC - GULF

MEXICO

- INDIAN

-

IRC - MEDITERRANEAN -

NORTH SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN GULF

RED

SEA - SEA

JAPAN - STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE - UNCLOS

- UNEP

WOC

- WWF

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Wikipedia

Gulf_of_Guinea New

York

Times 2014 The-great-invisible-on-the-deepwater-horizon-oil-spill

The

Economist Black Storm

Rising Wikipedia

Blowouts_well_drilling notable_offshore

Wikipedia

List_of_oil_spills

USNI

magazines

proceedings 2013 Africas leaking wound Energypedia

news Ghana Crossed

Crocodiles Gulf of Guinea Pipeline

dreams 2011 Gulf of Guinea is the new wild west UNEP

regional

seas marine litter Pellet

Watch maps Pelletwatch

google earth G

captain

gulf-of-guinea-oil-spill Gcaptain

nigeria-parliament-says-shell-pay-4-billion-2011-bonga-oil-spill http://gcaptain.com/tag/gulf-of-guinea-oil-spill/#.VaKblLXSMSU http://gcaptain.com/nigeria-parliament-says-shell-pay-4-billion-2011-bonga-oil-spill/#.VaKZU7XSMSU http://www.pelletwatch.org/earth/ http://www.pelletwatch.org/maps/map-3.html http://www.unep.org/regionalseas/marinelitter/publications/mpb/default.asp http://www.pipelinedreams.org/2011/05/gulf-of-guinea-the-new-wild-west/ https://crossedcrocodiles.wordpress.com/category/gulf-of-guinea/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulf_of_Guinea http://www.energy-pedia.com/news/ghana/new-154151 http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2013-03/africas-leaking-wound http://www.bsee.gov/About-BSEE/Divisions/EED/Marine-Trash-and-Debris-Program/ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/29/movies/the-great-invisible-on-the-deepwater-horizon-oil-spill.html http://www.marinetechnologynews.com/news/chevron-finds-deepwater-mexico-502566 http://www.economist.com/node/16059982

http://topics.bloomberg.com/gulf-of-mexico/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulf_of_Mexico

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blowout_%28well_drilling%29#Notable_offshore_well_blowouts

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_oil_spills

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Convention_for_the_Safety_of_Life_at_Sea

FICTION

- Operation

Neptune - An

advanced nuclear submarine is hijacked by environmental extremists intent on

stopping pollution from the burning of fossil fuels. The extremists,

dubbed 'Black Storm Rising' by the media, torpedo an

oil well in the Gulf of Mexico as the start of a campaign to cause energy chaos, with bigger

plans to come. If you enjoyed the movies: Battleship,

Under Siege or

The Hunt for Red

October, this is a

must for you.

|