|

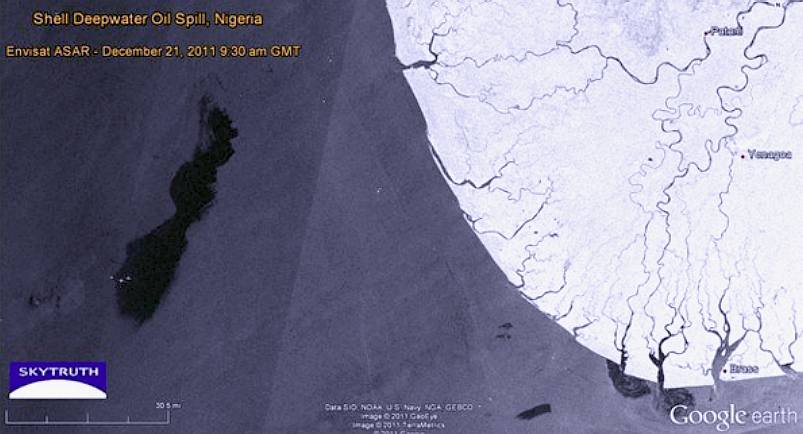

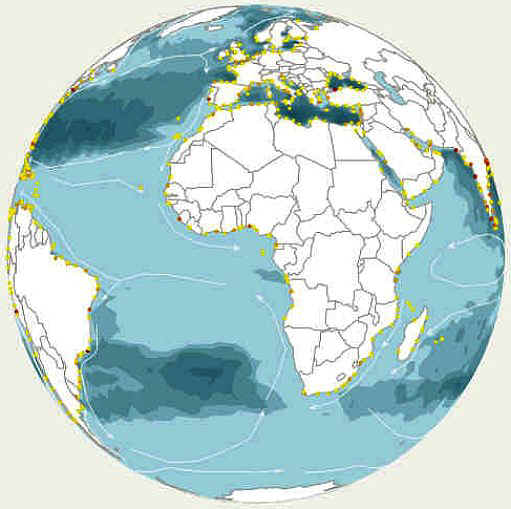

Google

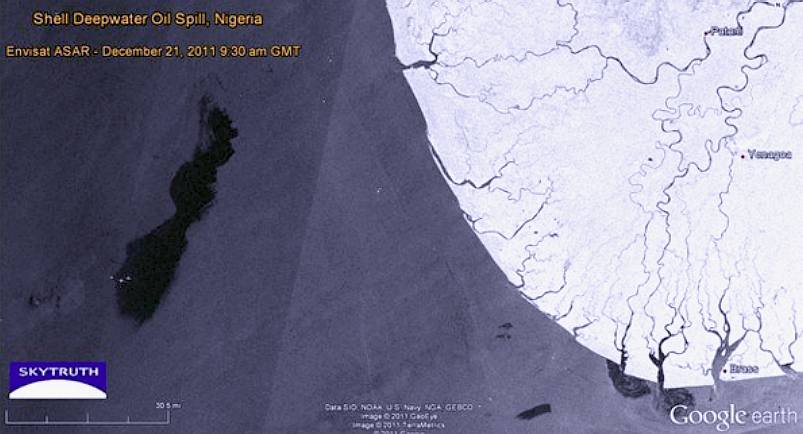

Earth map

of the West Africa and the Atlantic Ocean oil spill slick

G CAPTAIN JULY 17 2012

LONDON (Dow Jones) — Royal Dutch Shell PLC (RDSB.LN) could face a record $5 billion fine from authorities in Nigeria for an oil spill off the coast of the West African country last year, an amount that dwarfs similar fines in the U.S. and Brazil.

Shell pushed back hard against the penalty, proposed by federal authorities seven months after some 40,000 barrels of oil leaked at Shell’s Bonga offshore facility.

“We do not believe there is any basis in law for such a fine,” said a Shell spokesman. “Neither do we believe that Shell Nigeria Exploration and Production Company has committed any infraction of Nigerian law to warrant such a fine.”

The large penalty comes at a time of heightened concern over the safety of offshore oil production, following BP PLC‘s (BP) disastrous Deepwater Horizon explosion and oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Shell is currently facing intense scrutiny from U.S. authorities and environmental groups as it prepares to drill for oil offshore Alaska.

The fine is particularly severe in comparison to other recent incidents. Based on Shell’s estimate of the 40,000 barrels of oil spilled in the Bonga leak, the fine equates to around $125,000 a barrel.

By comparison, BP could face a fine under the clean water act for the Deepwater Horizon spill of up to $1,100 a barrel if it isn’t found guilty of gross negligence, or $4,300 a barrel if gross negligence is proved.

U.S. oil company Chevron Corp. (CVX) could have to pay between $8,000 and $10,000 a barrel for its spill of 3,000 barrels of oil offshore Brazil, according to recent comments from that country’s regulator.

The ultimate size of the fine will still have to be approved by a committee of Nigerian lawmakers, who Monday heard submissions from the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency, or NOSDRA, on what an appropriate penalty would be, according to local media reports. NOSDRA will have to justify to the House Committee on the Environment why

Shell should pay such a large amount.

Nigerian lawmakers were told to consider imposing the fine Monday by Peter Idabor, head of NOSDRA, according to local media reports. Mr. Idabor defended the decision, saying the $5 billion penalty was consistent with similar fines in other oil producing countries like Venezuela and

Brazil, the Vanguard newspaper reported.

If lawmakers decide to endorse Mr. Idabor’s recommendation, the fine will be the largest ever imposed on Shell. Even in Nigeria, where the firm has pumped commercial oil since the 1950s, Shell’s biggest charge to date was a $40.5 million court-imposed fine for a series of spills in Ogoniland dating back to the 1970s.

Shell was forced to halt production from the 200,000 barrel-a-day Bonga field in December after a leak occurred during a routine tanker loading operation. The result was one of Nigeria’s worst oil spills in more than a decade.

However, Shell claims that none of the crude reached land and that much of the leaked oil dispersed naturally in the water or evaporated. Some crude did wash up along the Western Niger Delta coastline, which Shell cleaned up, despite expressing doubts that it originated from Bonga.

“[Shell] responded to this incident with professionalism and acted with the consent of the necessary authorities at all times to prevent an environmental impact,” the company spokesman said.

CONTACT

SHELL

Royal Dutch Shell plc

(HQ)

Carel van Bylandtlaan 30

2596 HR DEN HAAG

The Netherlands

Postbus 162

2501 AN DEN HAAG

Tel. +31 70 377 9111

Shell U.K. Limited

Shell Centre

London, SE1 7NA

Tel. +44 (0) 20 7934 1234

Shell Luxembourgeoise

7 rue de l'Industrie

L-8069 BERTRANGE

Tel: 31 11 41 - 1

Fax: 31 11 41 - 745

Téléphone suivant: +352 311141715 ou alors ecrivez-nous

Email: shellstation-lu@shell.com

G CAPTAIN = NOVEMBER 26 2014

ABUJA, Nov 26 (Reuters) – Nigeria’s National Assembly said on Wednesday oil major Shell should pay $3.96 billion for a 2011 spill at its offshore Bonga oilfield in the latest assessment of damage to the environment.

The non-binding decision comes after years of analysis by various Nigerian state agencies, which have proposed a range of fines as high as $11.5 billion.

The parliament finally reached a decision based on the report of the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA), which previously recommended a fine of $5 billion.

Shell declined to comment. The company has previously said it took responsibility for the spill and had cleaned the area.

The parliament’s decision is non-binding as it only has the power to recommend fines to the government and cannot enforce them.

NOSDRA estimated that around 40,000 barrels were spilled when a tanker was loading crude at the offshore platform operated by Shell’s subsidiary SNEPCO. The Bonga field was producing 200,000 barrels per day at the time.

NOSDRA has previously said the spill had hurt locals in the area who rely on fishing for their livelihoods as the slick covered an area of around 950 square km.

“Since all efforts by this committee were tactfully rebuffed by SNEPCO, (it) has decided to adopt the damage assessment report submitted by NOSDRA as the lead agency in all oil spill management,” Uche Ekwunife, chairman of the environmental committee told the assembly.

Shell is also being pursued in a class action case for two other spills in the Niger Delta in 2008. In June, it offered 30 million pounds ($51 million) in compensation to 15,000 residents in the Bodo Community but this was rejected.

The United Nations Environment Programme has criticised

Shell in the past for not doing enough to clean up spills and maintain infrastructure.

Nigeria is Africa’s largest oil exporter and an OPEC member but the environmental toll has been huge. The mangrove creeks of the delta region are heavily polluted mainly due to leaks from illegal pipeline tapping and sabotage.

Foreign companies have been selling their stakes in onshore oilfields after becoming frustrated with industrial scale theft and resulting spills, which show no signs of abating.

On the 24th November 2014 Shell had to shut down a pipeline as a result of a new leak close to where it was removing oil taps.

(Writing by Julia Payne, editing by David Evans)

PULITZER

CENTER - JANUARY 2012

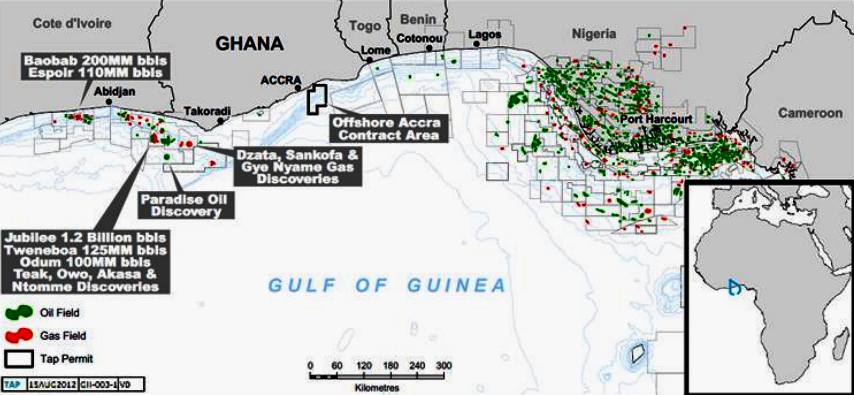

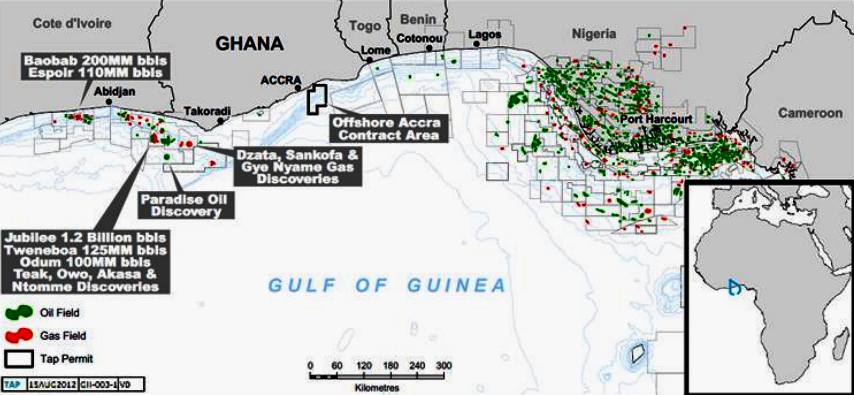

On November 3, 2011, fishermen working near the Jubilee oil field 60 km. off the coast of Ghana spotted a large oil slick floating towards land.

The next day a dark, syrupy ooze arrived onshore, coating beaches of several fishing communities and waterfront hotels in Ghana’s Ahanta West District, the coastal strip closest to the country’s new, deep water oil field.

The fishermen told authorities they suspected the spill came from the offshore operations, but the incident was greeted with seeming indifference. No official clean-up was launched, so the community was left to clean up the mess itself.

“The lack of any clear information about the incident has made many in the coastal communities nervous about the future,” said Kyei Kwadwo Yamoah of the Friends of the Nation, a Ghanaian community development organization.

Even as the Jubilee field was in development, environmentalists warned it was moving too fast. To activists, official silence surrounding the November incident was evidence that Ghana lacked the ability to properly oversee offshore oil operations.

Reports by non-governmental organizations show that the companies that developed the Jubilee field, and the World Bank Group officials who lent hundreds of millions of dollars to jumpstart the project, were aware of the risks from the beginning. What’s also clear is that everyone knew the Ghanaian government lacked adequate monitoring systems, regulators to police the industry and equipment needed to react to spills.

Located along Africa’s Atlantic Coast, Ghana is slipping down the same unregulated slope as other countries that hug the Gulf of Guinea: Promises of economic development along with a lure of easy money have prompted governments to encourage the rapid growth of an industry in a regulatory vacuum.

The oil industry, in effect, is left to monitor itself.

SPEEDY OIL DEVELOPMENT

Ghana’s Western Region boasts some of the country’s most striking coastline. Rocky coves and tidal pools give way to palm-fringed stretches of sandy beach where dolphins and sea birds dash in and out of crashing surf and where a lucky visitor might spot a nesting turtle.

Historically, the coastal region’s economy has depended on fishing, which benefits 2 million people – 8 percent of Ghana’s population – but is predicted to unduly suffer from pollution generated by oil operations. Government and industry officials acknowledge that they have no compensation fund to support fishing communities in the event of a major spill – the type of response that kick-started recovery in U.S. Gulf Coast states after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster.

That reality leaves many coastal residents and environmental activists doubting the government’s promise that in Ghana, oil would be a blessing, not a curse.

What they’ve seen instead is a fast embrace of the industry: local boosters quickly adopted the nickname “Oil City” for the coastal region’s capital, Sekondi-Takoradi.

When U.K.-based Tullow Oil announced in June 2007 that it had discovered oil in commercial quantities, no one expected that crude would flow just three and a half years later. At the time, Tullow officials spoke of needing up to seven years to develop the field.

But boosted by $215 million in loans from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) – the private financing arm of the World Bank – Tullow and its partners, the American companies Kosmos Energy and Anadarko Petroleum Corporation, were able to get the $3 billion Jubilee field ready in record time.

Ghana became the latest West African country to share in an oil exploration boom that had taken on new emphasis after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

Companies like ExxonMobil and

Chevron-Texaco had been major players in Equatorial Guinea, Angola and Nigeria since the 1990s. After the terrorist attacks, the United States looked increasingly to Africa as a “safe” alternative to Middle Eastern oil.

Then-President George W. Bush traveled twice to sub-Saharan Africa and met with a number of African heads of state. Exploration in the Gulf of Guinea was pushed by rising oil prices and advances in deep-water drilling technology. Nine years later the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster gave African offshore development an unexpected boost.

FROM ONE GULF TO ANOTHER

“The moratorium on deep-water drilling in the Gulf of Mexico left a lot of drilling rigs with nothing to do and then the oil companies are faced with these half-a-million-dollar-a-day contracts with nothing to do,” said Stuart Wheaton, development director for Tullow Oil Ghana.

Operators moved rigs from the Gulf of Mexico to oil fields around the world and some made it to West African waters.

In those same waters, Ghana’s offshore development had gotten its head start from the IFC, whose loans served as a “green light” for other potential investors.

Mary-Jean Moyo, the IFC’s country manager for Ghana, said the corporation’s financial backing in 2009 was crucial in attracting other private investors to the Jubilee project.

“This was at the height of the global financial crisis, so IFC played quite a critical role in terms of being a catalyst,” Moyo said. Without the IFC, “it might have been difficult to raise additional international financing.”

Moyo also said the Jubilee project was classified as low risk for Ghana because “this is offshore and there weren’t any onshore impacts in terms of social displacement, in terms of destruction to mangroves.”

But oil industry analysts at Oxfam America, the global relief and development organization, said the IFC agreed to help finance the project before fully addressing safety and environmental concerns. Moyo acknowledged that the IFC loans to Tullow Oil and Kosmos Energy were approved before the required environmental impact studies had been completed. She pointed out that IFC financing followed strict rules, including “adherence to international safety standards in terms of having very good oil spill response plans and adequate safety measures.”

Ian Gary, Oxfam’s top expert on extractive industries, said this sent a bad signal: “Bringing the project to a board vote prior to the completion of the environmental Impact assessment weakens international norms, since one of the basic purposes of an (assessment) is to determine whether, and under what conditions, a project should be supported.”

In a review of environmental documentation prepared by the IFC, the environmental organization Pacific Environment also questioned IFC support for the project, citing: “Inadequate assessment of impacts on endangered species and critical habitats; inadequate assessment of noise impacts on marine mammals, dumping of drilling wastes into the sea,” and a failure to demonstrate compliance with international standards.

Industry officials say the risks of the Jubilee development are manageable.

“It’s fair to say the capacity and capability for national emergency response is low, but we’ll just have to keep working at it as the years go by,” said Tullow Oil’s Wheaton.

“Everything has some sort of risk associated with it, so you try to minimize those risks and if we do have a spill, what we have done is we’ve brought equipment in,” he added.

The company has clean-up equipment on-site and is a member of the industry-funded Oil Spill Response Ltd., an organization that says it can airlift equipment from the U.K. within 24 hours in the event of a major spill.

Mohammed Amin Adam, a government transparency advocate and cofounder of Ghana’s Civil Society Platform on Oil and Gas said his country doesn’t even have “the legal … frameworks to respond to these issues.”

Even though Jubilee field production has started, Ghana has yet to update environmental laws governing extractive industries that were written a generation ago. Ghanaian officials said new legislation will be considered this year.

Ghanaian environmental officials also said they are prepared to act in case of a spill.

“There’s a National Security Coordinating Committee involving the military, the navy, the police and local councils … the Ministry, the Maritime Authority,” said Sherry Ayittey, Ghana’s environment minister. “There is an emergency response unit always being trained, so that in the event of a spillage, within 24 hours, we would be able to move to the location and then handle the issue as quickly as possible.”

REGULATORY VACUUM

Production from the Jubilee field hovers at around 80,000 barrels per day, but that’s expected to increase substantially over the next decade.

At Ghana’s April 2011 Oil and Gas Summit, Willy Olsen, former senior adviser to Norway’s Statoil, predicted Ghana would become the region’s third-largest producer after Nigeria and Angola, “pumping upwards of 500,000 barrels per day.”

As proof of their technical expertise, Ghanaian government and oil company officials have touted the pace at which the Jubilee field was brought to production.

Environmentalists point out that the country’s first deep-water oil project was its first major oil project of any kind.

Amid the ramp-up to commercial production, the Deepwater Horizon spill occurred. The blowout of the Macondo well off the Louisiana coast on April 20, 2010 was an “eye-opener” according to one Ghanaian official, who said the blast prompted the government to review all of its safety procedures.

The Deepwater Horizon disaster did not slow down Jubilee development, however, and the government review has yet to yield any new regulation.

In October 2011, Offshore Magazine reported on a deep-water technology conference in New Orleans where Dennis McLaughlin, Senior Vice President with Kosmos Energy, gave a talk titled, “Reviewing Lessons learned from the Jubilee project.” In it he acknowledged that, “large deep-water projects are inherently difficult and risky,” and then described what it was like to develop the Jubilee field in a country with no regulatory or commercial infrastructure.

During the Jubilee field development Kosmos Energy experienced several mishaps. The company acknowledged spilling toxic drilling mud on three occasions, including a spill of some 600 barrels (25,000 gallons) in December 2009.

Cephas Egbefome an environmental issues researcher for Ghana’s parliament, said the government fined Kosmos $35 million for negligence.

But the fine, which Kosmos challenged as not following Ghanaian law and ultimately did not pay, raised a number of concerns, Egbefome said. The government probe was quick and opaque; the methodology for determining the fine was unclear. “Kosmos openly challenged the legal basis of the fine, describing it as totally unlawful,” he said.

Transparency activist Mohammed Amin Adam takes up the story:

“What the law says is that in the event of a disaster, a spill, the polluter must pay. But the law doesn’t talk about a fine,” he said. “Kosmos spilled mud, a committee was set up to investigate Kosmos and the committee came out with a fine, contrary to our law.

“What government needed to do was to get Kosmos to clean and pay for the cleaning,” Amin Adam said. “We just slapped a fine on them. And so they came to raise legal questions: whether we had the legal mandate, the authority to slap a fine on them.”

Kosmos declined to answer questions about the mud spills.

Instead Jim McCarthy, the media relations representative for the company sent ICIJ a press release on the “amicable” resolution of several issues: “Kosmos and the Ministry of Science, Environment and Technology have agreed to a solution with respect to the accidental mud discharges offshore Ghana earlier this year whereby Kosmos would support the Ministry’s efforts to build capacity in the environmental sector.”

Daniel Amlalo, Ghana’s acting Enviromental Protection Agency director, said the mud spills were properly addressed.

“Lessons have been learned from that and government has put measures in place to ensure that it does not happen again,” he said.

A REGIONAL PROBLEM

Ghana’s troubled regulation of the offshore oil industry sits against a backdrop of other West African nations with dubious environmental records.

The Nigerian oil industry, already infamous for its disastrous environmental record in the Niger Delta, also has problems offshore. In December, Shell said a spill occurred at its Bonga field, approximately 120 km. off Nigeria’s coast.

This past December 20th and 21st, oil spewed from a ruptured fuel line connecting the Bonga platform to a waiting tanker. Before workers noticed the spill, Shell said that up to 40,000 barrels (1.68 million gallons) had leaked, reportedly making it the worst offshore accident in Nigeria since 1988.

The Nigerian government takes a hands-off approach to clean-up operations, maintaining little in the way of vessels or equipment. Each company operating in the country is required to stockpile clean-up equipment and the industry leaders in Nigeria have also enlisted the U.K.’s Oil Spill Response Ltd.

After the December spills, Nigerian Senator Abubakar Kukola Saraki denounced the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency for having to “rely almost exclusively on the grace and benevolence of the oil companies” in a clean-up effort.

After years of denial, Royal Dutch Shell recently acknowledged that “operational issues” were responsible for two other large spills in Nigeria’s Ogoniland in 2008 – pollution in the Niger Delta that the United Nations Environment Program said would cost $1 billion to clean up.

Shell said sabotage is thwarting clean-up efforts and more than three years later, oil remains in the water and on land. A November 2011 report from Amnesty International says the spills destroyed the livelihoods of 69,000 people.

Angola offers another bad example, said Kristin Reed, an environmental researcher at the Human Rights Center at the University of California, Berkeley.

Reed described Angola’s oil industry as one without any state or independent monitoring or oversight. She said the situation is made worse by Angola’s press restrictions that limit public information about oil operations. Anecdotal news of spills and pollution sometimes spreads via blogs and the Internet but official details on incidents and who’s to blame are rarely available.

And the tiny nation of Equatorial Guinea, an oil producer since the mid-1990s, also has no spill response plan, no clean-up equipment or vessels, no independent press and no agreements with neighboring countries to combat pollution.

In Equatorial Guinea, oil companies monitor themselves and handle their own cleanups.

The ICIJ asked ExxonMobil, how the oil companies conduct self-monitoring in the region and to whom they report.

David Eglinton, a spokesman for ExxonMobil, promised a response. He has yet to give one.

DEAD WHALES

In Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana’s “Oil City,” activists from Friends of the Nation work with the communities closest to offshore drilling operations.

In two years of monitoring on behalf of local residents, the group’s Kyei Yamoah, has noted an increase in whale deaths.

“A whale washed ashore in October, bringing the total number of dead

whales on our beaches since late 2009 to eight,” Yamoah said.

“After the death of the first whale, (the government) claimed they had taken samples to determine the cause, but they have never made their reports public,” Yamoah said. “Now we have seven more [dead whales].”

This past spring, the Civil Society Platform on Oil and Gas, a group that includes industry experts, government officials and community activists, issued a “report card” on Ghana’s emerging oil business. Speakers at the report’s unveiling included Alhaji Inusah Fuseini, Ghana’s deputy energy minister, and Ishac Diwan, the World Bank’s Ghana country director.

The report commended the government’s transparency efforts and the passage of an oil revenue management plan, but gave the industry and government regulators a “D” grade on social and environmental issues. The report said pollution controls and environmental regulation of the offshore industry are still just legislative proposals.

Ghanaian transparency advocate Mohammed Amin Adam said the report was designed to draw attention to the potential danger the country faces.

The attention is needed, said Ghanaian government researcher Cephas Egbefome, because the environment and risks in offshore oil production seem to be non-issues for most politicians and the public.

In a country where a significant percentage of the population struggles just to get by, Egbefome said, it’s hard to muster much concern for an oil operation 60 km offshore that few can see.

by

Christiane Badgley

G CAPTAIN DECEMBER 25 2011

IBADAN, Nigeria (Dow Jones)–Shell Petroleum Production Co., or SNEPCo, on Sunday said the oil leak from its Bongo facility off the Nigerian coast has “largely been dispersed.”

About 40,000 barrels of oil leaked five days ago during a routine operation to transfer oil from Bonga’s floating production, storage and offtake, or FPSO, vessel to an oil tanker.

Tony Okonedo, SNEPCo’s media relations officer, said in a statement that the company has confirmed the oil leak has “largely been dispersed and it will continue to monitor the area, including using satellite, and take appropriate steps to disperse any further persistent oil sheens.”

He said since the leak, teams from SNEPCo, an affiliate of Royal Dutch Shell PLC (RDSA, RDSB), have worked “around the clock” with international oil spill experts, using a combination of dispersants and booms to tackle the leaked oil.

Shell said it became aware of the leak on Tuesday at its Bonga field, about 120 kilometers off Nigeria. Production was reported to have stopped at the field, which has a capacity of 200,000 barrels a day.

Okonedo didn’t say when production will likely resume at the Bonga facility.

Reacting in the statement to the news of the oil dispersal, Shell Nigeria Country Chair Mutiu Sunmonu said, “I am very sorry the leak from Bonga happened in the first place, but I am now happy to confirm the oil has dispersed.”

He also thanked the teams that “worked day and night to clean up the oil for their tireless efforts, and the communities along the western Delta shoreline for their “support and understanding over recent days.”

By Obafemi Oredein, Dow Jones Newswires

G CAPTAIN DECEMBER 22 2011

LONDON — Royal Dutch Shell PLC (RDSA) is sending ships and planes loaded with chemical dispersants in an effort to clean up as much as 40,000 barrels of crude oil spilled into the Gulf of Guinea, the head of the company’s Nigerian operations said Thursday.

Shell said production at the 200,000 barrel a day Bonga field offshore Nigeria has now been completely halted after a leak occurred Tuesday during a tanker loading operation, resulting in what may be the country’s worst oil spill in more than a decade.

“To accelerate the clean-up at sea, we are deploying vessels with dispersants to break up the oil sheen at sea. We are mobilizing airplanes that will support the vessels in this operation,” said Shell Nigeria Chairman Sunmonu.

The company said that “up to 50% of the leaked oil has already dissipated due to natural dispersion and evaporation,” but this hasn’t been independently verified. Nigeria’s Department of Petroleum Resources and the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency weren’t immediately available for comment when contacted by Dow Jones Nigeria.

Shell said it believes the leak occurred during a routine operation to transfer crude oil from Bonga’s floating production, storage and off-loading vessel to a waiting oil tanker. An export line connecting the vessel to the tanker was closed off and the oil flow halted.

The spill is likely Nigeria’s worst since Exxon Mobil Corp.’s (XOM) Idoho platform leaked an estimated 40,000 barrels into the sea in 1998. The incident is Shell’s first major offshore oil spill in Nigeria, although the company’s operations onshore the West African country have been blamed for decades of pollution by environmental and human rights groups.

Sunmona reiterated that he was very sorry the spill had happened. “Let me also mention that we are currently working with the Nigerian government to inform local communities and fishermen about the situation,” he said.

Bonga, which lies 120 kilometers off the Nigerian coast, is one of Nigeria’s largest oil fields, contributing around 8% of the country’s crude loadings in 2011, according to JBC Energy.

The spill is likely to lend support to Atlantic Basin light crude and could have extensive price consequences if volumes are taken out of the market for a long time, said JBC.

ACCRA

JOINT VENTURE - JV partner Tap Oil has announced the award by the Accra Joint Venture of the Drilling Rig Services contract for the drilling of the Starfish Prospect to Stena Drilling. The Starfish-1 well will be drilled by the Stena DrillMAX, Dual Derrick Drillship which has recently drilled eight efficient and successful wells in Ghana. Stena Drilling has extensive experience in Ghana and is providing this latest generation rig at competitive day rates in conjunction with an existing West African drilling program, thereby minimising mobilisation and demobilisation charges for the Accra Joint Venture.

Starfish-1 is a wildcat well expected to spud in June 2013. The well will target a large, fan complex in the deep water of eastern Ghana, interpreted to be potentially comparable to the Jubilee field in western Ghana. Tap estimates that the well will target prospective resources potentially in the order of half a billion barrels (431 mmbbls (P50); 665mmbbls (PMean)).

The Offshore Accra Contract Area is located in an emerging oil province on the West Africa Transform Margin, along the northern Gulf of Guinea. A number of discoveries have been made in a variety of comparable geological settings along this margin. In 2007, the Jubilee field (one of the largest oil discoveries in the world in 2007) was discovered by Kosmos Energy and Tullow Oil, establishing a new deepwater play offshore Ghana. Subsequent discoveries in Ghana (Tweneboa, Odum, Owo, Teak, Akasa, Dzata, Sankofa, Gye Nyame and Paradise) and in the Liberian Basin (Venus and Mercury) have further demonstrated the potential that exists along the whole margin.

The Accra Joint Venture, with participating interests, comprises: Ophir Ghana (Accra) (Operator) 20%; Afex Oil (Ghana) 20%; Vitol Upstream (Accra) 30%; Rialto Energy (Ghana)* 12.5%; Tap Oil (Ghana) 17.5%; Ghana National Petroleum Corp** 10% carried.

* The entry of Rialto Energy (Ghana) remains conditional on it providing a letter of credit in respect of its participating interest share of the approved work program and budget for the current Exploration Period.

**Carried by the other parties in proportion to their Participating interest. GNPC has the option of increasing its interest in the event of a commercial discovery.

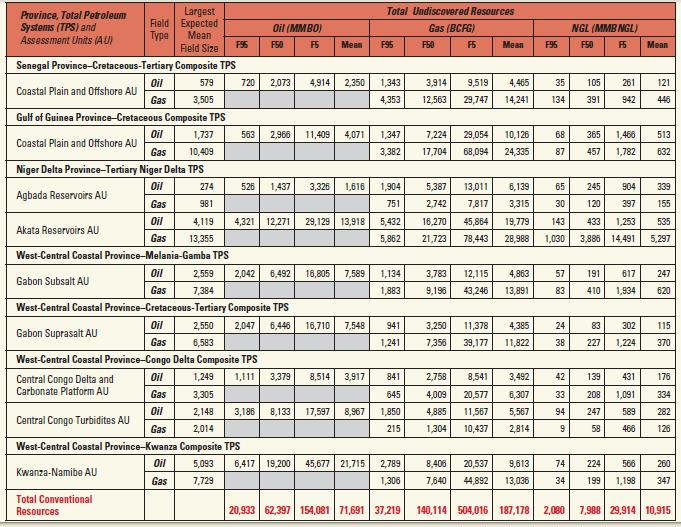

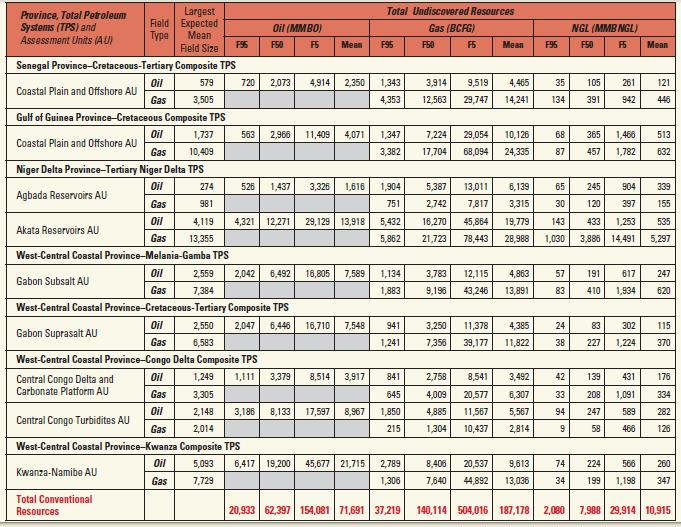

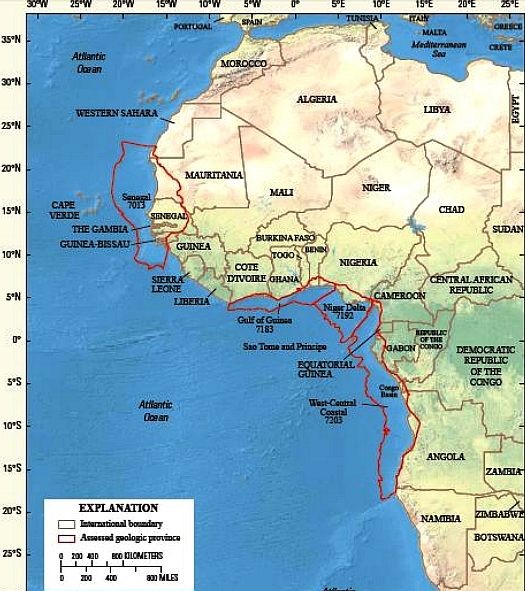

OIL

TABLE - West Africa Provinces assessment results for undiscovered, technically recoverable oil, gas, and natural gas liquids.

Largest expected mean field size in million barrels of oil and billion cubic feet of gas; MMBO, million barrels of oil. BCFG, billion cubic feet of gas. MMBNGL, million barrels of natural gas liquids. Results shown are fully risked estimates. For gas accumulations, all liquids are included as natural gas liquids (NGL). Undiscovered gas resources are the sum of nonassociated and associated gas. F95 represents a 95 percent chance of at least the amount tabulated; other fractiles are defined similarly. AU, assessment unit; AU probability is the chance of at least one accumulation of minimum size within the AU. NGL, natural gas liquids. TPS, total petroleum system. Gray shading indicates not applicable.

OBIAGELI

(OBY) EZEKWESILI - is a former Vice President of the World Bank for Africa, a former Nigerian Education Minister and co-founder of Transparency International.

‘Oby’ first served the Nigerian government as Head of the Budget Monitoring and Price Intelligence Unit, where she led reforms to public procurement. She was appointed Minister of Solid Minerals in 2005 and chaired the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. In 2006 she became Minister of Education, until taking up her World Bank post in 2007. Prior to working for the Government of Nigeria, Dr Ezekwesili was at the Center for International Development at Harvard University. Having co-founded the anti-corruption organisation Transparency International, she directed its work in Africa. She is also a Senior Economic Advisor to Open Society, which aims to build vibrant and tolerant societies with democratically accountable governments.

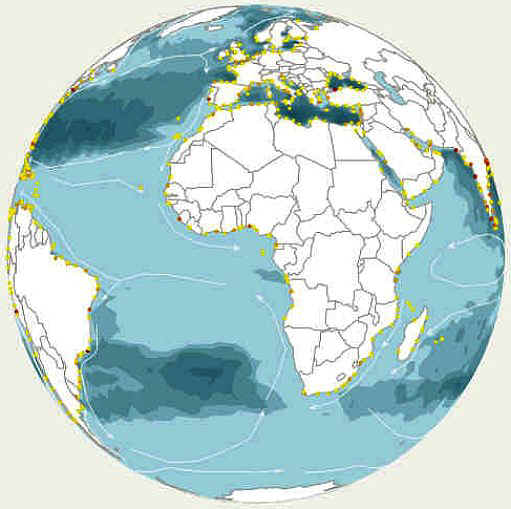

THE

GLOBAL

OCEAN COMMISSIONERS

- Your representative for the GOC is shown on this map of the world showing the location of the

Commissioners. ‘Oby’ Ezekwesili is the most appropriate contact for

West Africa.

INTERGOVERNMENTAL OCEANOGRAPHIC COMMISSION (Of UNESCO)

JOINT IOC XJNIDO WORKSHOP ON MARINE DEBRIS/WASTE MANAGEMENT FOR THE GULF OF GUINEA

- 18 June 1999

Abidjan, Cote d’hoire, 19-21 April 1999 the management process and audits

the results. The challenge is to create a competent and trusted institution

to foster a successful, long-term stewardship process.

To combat marine debris, the introduction of co-management as a capacity building strategy is a necessity for the countries of the Gulf of Guinea.

Co-management is defined as a joint management arrangement, an institutional

arrangement in which responsibility for resource management, conservation and/or economic development is shared between governments and user

groups.

Co-management provides opportunity for government to refocus from micro management to macro

frameworks. Stakeholders can assume responsibilities for management decisions while government sets overall

objectives.

This

was a good start to engaging those responsible for managing the area, but

what happened?

SECRETARIAT

Dr Jacques ABE

Centre de Recherches Oceanologiques

Large Marine Ecosystem Project for the Gulf of Guinea

BP V 18 ABIDJAN - Cote d’lvoire

Tel: 35-50-14/35-58-80/08-58-00

Fax: 35- 1 l-55125-73-69

E-mail: Abe@cro.orstom.ci

E-mail: gog-lme@afiicaonline.co.ci

Mr Julian BARBIERE

Programme Specialist

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission

UNESCO

I rue Miollis

75735 Paris Cedex 15

Tel: 3301 4568 4045

Fax: 3301 4568 5812

E-mail: j.barbiere@unesco.org

AFRICA'S LEAKING WOUND - OIL BASED PIRACY

ACROSS THE GULF, MARCH 2013

Like blood from a leaking wound, the piracy that is spreading westward from Nigeria has now reached the Ivory Coast, 400 miles from its origins on the inland and coastal waters of the Niger Delta. There, and on the waters more than 100 miles off these countries’ coasts, acts of depredation against ships and fixed oil installations have resulted in far greater financial losses and had a far wider economic impact that any piracy seen so far anywhere else in the world.

International concern has been growing for some time. The U.N. Security Council (UNSC), having expressed its alarm about piracy in the Gulf of Guinea in August 2011, passed resolution 2018 two months later, re-emphasizing that concern and urging regional states to take effective action against the pirates’ backers and financiers. 1 The Economic Community of West and Central Africa and the Gulf of Guinea Commission assessed that piracy was “rapidly spreading around the region and increasingly dovetailing into oil bunkering, robbery at sea, hostage-taking, human and drug trafficking, terrorism and corruption,” while resource shortfalls and inadequate legal frameworks meant that piracy suspects were being released.

This despite the fact that the International Maritime Organization had been working with the Maritime Organization of West and Central Africa for nearly four years to develop a coast-guard network and improve regional maritime security cooperation.

Are they right to be worried? Context matters, and West African piracy cannot be viewed separately from the larger issues of Salafist violence spreading from the interior, consequent religious and intercommunal violence in the more populous areas closer to the coast, endemic corruption, links between elites and criminals, massive income inequality, the prospect of state failure, and, standing behind all those, the insatiable need for oil and gas that fuels the competitive behavior of states, international oil companies, and domestic elites.

The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) reports that Gulf of Guinea piracy attacks were generally up in 2012 over 2011, the only decline occurring off Benin. In terms of actual numbers the IMB reports 58 incidents for the region as a whole in 2012 compared with 51 in 2008 (the previous high point) and 44 in 2011.

That compares with 75 incidents off Somalia in 2012 versus 237 in 2011. However, the reliability of piracy statistics has always been questionable, none more so than for Nigeria, where some commentators have suggested that rates of under-reporting may be closer to 80 percent than the 50 percent that has been the rule of thumb elsewhere.

CORRUPTION ENTRENCHED EPIDEMIC

The root of the problem, and the principal obstacle to resolving the social and ethnic unrest in the Niger Delta, is corruption at all levels of government. Inequalities of income feed the problem: Nigeria is the continent’s second largest economy yet had a poverty rate of 70 percent in 2007, while at the same time billions of dollars of oil revenue disappeared into the overseas bank accounts of corrupt politicians and officials. Large sections of Nigerian society do not trust their own government. Crime is a national epidemic; one that the police

- lacking adequate pay, training, or numbers - seemingly aid and abet through their own predatory behavior. The enormous sums involved in oil theft

- known as illegal bunkering - attracted the interest of military figures early on who demanded payment to look the other way.

Once the country returned to civilian rule in 1999, oil revenue was decentralized, and so was corruption. By 2009, for example, the income of Rivers State alone was, at $2.9

billion, greater than that of several African countries. With more money in their hands, state governors saw their wealth and patronage power increase immeasurably. Politicians quickly recognized the advantages of associating with the well-funded and well-armed oil bunkering gangs, although the gangs’ political allegiance was never strong.

The best-known and most successful of the numerous militant organizations that sprang up was MEND, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta. Formed in late 2005 by a collection of pre-existing groups, it essentially disbanded, at least in its original manifestation, following the announcement of the 2009 amnesty.

It was never a unified entity. Some judged it to have been a primarily criminal organization despite its very public claims to the contrary. Others, while not denying the criminal element, pointed to the federal government’s reluctance to provide security in situations that were not directly oil-related. Such selective application of law enforcement, along with other social pressures, had led each tribe to form armed groups to defend its interests; by the early 2000s those very groups had begun to drift into criminality, particularly illegal bunkering.

Rising oil prices have ensured that oil theft remains highly profitable. Leaked U.S. diplomatic cables suggest those linked to shady deals have included the wife of a former president and unnamed high-ranking politicians in the nation’s capital, Abuja. Unconfirmed reports assert that Lebanese nationals possibly funding the terrorist groups Hamas and Hezbollah, the Russian mafia, and drug cartels may also be involved. None of that theft would be possible on land or at sea without the complicity of many in Nigeria’s political elite, the national oil company, and the military.

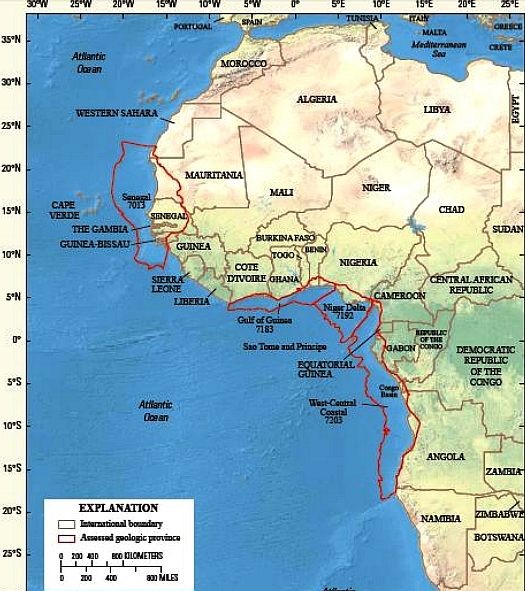

RED

INK - Four geologic provinces located along the northwest and west-central coast of Africa recently were assessed for undiscovered oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids resources as part of the U.S. Geological Survey’s

(USGS) World Oil and Gas Assessment. Using a geology-based assessment methodology, the USGS estimated mean volumes of 71.7 billion barrels of oil, 187.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 10.9 billion barrels of natural gas liquids.

Estimated undiscovered and recoverable oil and natural gas off the coast of Ivory Coast, extending through Ghana, Togo, Benin, and the western edge of Nigeria.: 4,071 MMBO, million barrels of oil, 34,451 BCFG, billion cubic feet of gas, and 1,145 MMBNGL, million barrels of natural gas liquids, for the Coastal Plain and Offshore AU in the Gulf of Guinea Province, outlined in red. This does not include current existing discoveries, or fields already in production. Note that it extends along the entire coast of Ivory Coast.

OIL

SPILL MINI HISTORY

|

Year

|

Rig

Name

|

Rig

Owner

|

Type

|

Damage

/ details

|

|

1955

|

S-44

|

Chevron

Corporation

|

Sub

Recessed pontoons

|

Blowout

and fire. Returned to service.

|

|

1959

|

C.

T. Thornton

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire damage.

|

|

1964

|

C.

P. Baker

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Drill

barge

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico, vessel capsized, 22 killed.

|

|

1965

|

Trion

|

Royal

Dutch Shell

|

Jackup

|

Destroyed

by blowout.

|

|

1965

|

Paguro

|

SNAM

|

Jackup

|

Destroyed

by blowout and fire.

|

|

1968

|

Little

Bob

|

Coral

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire, killed 7.

|

|

1969

|

Wodeco

III

|

Floor

drilling

|

Drilling

barge

|

Blowout

|

|

1969

|

Sedco

135G

|

Sedco

Inc

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

damage

|

|

1969

|

Rimrick

Tidelands

|

ODECO

|

Submersible

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1970

|

Stormdrill

III

|

Storm

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire damage.

|

|

1970

|

Discoverer

III

|

Offshore

Co.

|

Drillship

|

Blowout

(S. China Seas)

|

|

1971

|

Big

John

|

Atwood

Oceanics

|

Drill

barge

|

Blowout

and fire.

|

|

1971

|

Wodeco

II

|

Floor

Drilling

|

Drill

barge

|

Blowout

and fire off Peru, 7 killed.

|

|

1972

|

J.

Storm II

|

Marine

Drilling Co.

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1972

|

M.

G. Hulme

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and capsize in Java Sea.

|

|

1972

|

Rig

20

|

Transworld

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Martaban.

|

|

1973

|

Mariner

I

|

Sante

Fe Drilling

|

Semi-sub

|

Blowout

off Trinidad, 3 killed.

|

|

1975

|

Mariner

II

|

Sante

Fe Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Lost

BOP during blowout.

|

|

1975

|

J.

Storm II

|

Marine

Drilling Co.

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico.

|

|

1976

|

Petrobras

III

|

Petrobras

|

Jackup

|

No

info.

|

|

1976

|

W.

D. Kent

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Damage

while drilling relief well.

|

|

1977

|

Maersk

Explorer

|

Maersk

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire in North Sea

|

|

1977

|

Ekofisk

Bravo

|

Phillips

Petroleum

|

Platform

|

Blowout

during well workover.

|

|

1978

|

Scan

Bay

|

Scan

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire in the Persion Gulf.

|

|

1979

|

Salenergy

II

|

Salen

Offshore

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1979

|

Sedco

135F

|

Sedco

Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

and fire in Bay of Campeche Ixtoc

I well.

|

|

1980

|

Sedco

135G

|

Sedco

Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

and fire of Nigeria.

|

|

1980

|

Discoverer

534

|

Offshore

Co.

|

Drillship

|

Gas

escape caught fire.

|

|

1980

|

Ron

Tappmeyer

|

Reading

& Bates

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Persian Gulf, 5 killed.

|

|

1980

|

Nanhai

II

|

Peoples

Republic of China

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

of Hainan Island.

|

|

1980

|

Maersk

Endurer

|

Maersk

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Red Sea, 2 killed.

|

|

1980

|

Ocean

King

|

ODECO

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire in Gulf of Mexico, 5 killed

|

|

1980

|

Marlin

14

|

Marlin

Drilling

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

in Gulf of Mexico

|

|

1981

|

Penrod

50

|

Penrod

Drilling

|

Submersible

|

Blowout

and fire in Gulf of Mexico.

|

|

1985

|

West

Vanguard

|

Smedvig

|

Semi-submersible

|

Shallow

gas blowout and fire in Norwegian sea, 1 fatality.

|

|

1981

|

Petromar

V

|

Petromar

|

Drillship

|

Gas

blowout and capsize in S. China seas

|

|

1983

|

Bull

Run

|

Atwood

Oceanics

|

Tender

|

Oil

and gas blowout Dubai, 3 fatalities.

|

|

1988

|

Ocean

Odyssey

|

Diamond

Offshore Drilling

|

Semi-submersible

|

Gas

blowout at BOP

and fire in the UK North Sea, 1 killed.

|

|

1988

|

PCE-1

|

Petrobras

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

at Petrobras PCE-1 (Brazil) in April 24. Fire burned for 31

days. No fatalities.

|

|

1989

|

Al

Baz

|

Sante

Fe

|

Jackup

|

Shallow

gas blowout and fire in Nigeria, 5 killed.

|

|

1993

|

M.

Naqib Khalid

|

Naqib

Co.

|

Naqib

Drilling

|

fire

and explosion. Returned to service.

|

|

1993

|

Actinia

|

Transocean

|

Semi-submersible

|

Sub-sea

blowout in Vietnam.

|

|

2001

|

Ensco

51

|

Ensco

|

Jackup

|

Gas

blowout and fire, Gulf of Mexico, no casualties

|

|

2002

|

Arabdrill

19

|

Arabian

Drilling Co.

|

Jackup

|

Structural

collapse, blowout, fire and sinking.

|

|

2004

|

Adriatic

IV

|

Global

Sante Fe

|

Jackup

|

Blowout

and fire at Temsah platform, Mediterranean Sea

|

|

2007

|

Usumacinta

|

PEMEX

|

Jackup

|

Storm

forced rig to move, causing well blowout on Kab

101 platform, 22 killed

|

|

2009

|

West

Atlas / Montara

|

Seadrill

|

Jackup

/ Platform

|

Blowout

and fire on rig and platform in Australia.

|

|

2010

|

Deepwater

Horizon

|

Transocean

|

Semi-submersible

|

Blowout

and fire on the rig, subsea well blowout, killed 11 in

explosion.

|

|

2010

|

Vermilion

Block 380

|

Mariner

Energy

|

Platform

|

Blowout

and fire, 13 survivors, 1 injured.

|

|

2012

|

KS

Endeavour

|

KS

Energy Services

|

Jack-Up

|

Blowout

and fire on the rig, collapsed, killed 2 in explosion.

|

|

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BERING

- CARIBBEAN - CORAL - EAST

CHINA

ENGLISH CH

-

GOC - GULF

MEXICO

- INDIAN

-

IRC - MEDITERRANEAN -

NORTH SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN GULF - SEA

JAPAN

STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE - UNCLOS

- UNEP

WOC

- WWF

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Shell

International Shell

UK Wikipedia

Royal_Dutch_Shell Wikipedia

Gulf_of_Guinea New

York

Times 2014 The-great-invisible-on-the-deepwater-horizon-oil-spill

The

Economist Black Storm

Rising Wikipedia

Blowouts_well_drilling notable_offshore

Wikipedia

List_of_oil_spills

USNI

magazines

proceedings 2013 Africas leaking wound Energypedia

news Ghana Crossed

Crocodiles Gulf of Guinea Pipeline

dreams 2011 Gulf of Guinea is the new wild west UNEP

regional

seas marine litter Pellet

Watch maps Pelletwatch

google earth G

captain

gulf-of-guinea-oil-spill Gcaptain

nigeria-parliament-says-shell-pay-4-billion-2011-bonga-oil-spill Pulitzer

Center

Ghana-oil-offshore-drilling-boom-industry-environmental-safety-spill-disaster-plan-jubilee-west-africa-gulf-of-guinea http://www.shell.com/ http://www.shell.co.uk/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Dutch_Shell http://gcaptain.com/tag/gulf-of-guinea-oil-spill/#.VaKblLXSMSU http://gcaptain.com/nigeria-parliament-says-shell-pay-4-billion-2011-bonga-oil-spill/#.VaKZU7XSMSU http://www.pelletwatch.org/earth/ http://www.pelletwatch.org/maps/map-3.html http://www.unep.org/regionalseas/marinelitter/publications/mpb/default.asp http://www.pipelinedreams.org/2011/05/gulf-of-guinea-the-new-wild-west/ https://crossedcrocodiles.wordpress.com/category/gulf-of-guinea/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulf_of_Guinea http://www.energy-pedia.com/news/ghana/new-154151 http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2013-03/africas-leaking-wound http://www.bsee.gov/About-BSEE/Divisions/EED/Marine-Trash-and-Debris-Program/ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/29/movies/the-great-invisible-on-the-deepwater-horizon-oil-spill.html http://www.marinetechnologynews.com/news/chevron-finds-deepwater-mexico-502566 http://www.economist.com/node/16059982

http://topics.bloomberg.com/gulf-of-mexico/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gulf_of_Mexico

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blowout_%28well_drilling%29#Notable_offshore_well_blowouts

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_oil_spills

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Convention_for_the_Safety_of_Life_at_Sea

FICTION

- Operation

Neptune - An

advanced nuclear submarine is hijacked by environmental extremists intent on

stopping pollution from the burning of fossil fuels. The extremists,

dubbed 'Black Storm Rising' by the media, torpedo an

oil well in the Gulf of Mexico as the start of a campaign to cause energy chaos, with bigger

plans to come. If you enjoyed the movies: Battleship,

Under Siege or

The Hunt for Red

October, this is a

must for you.

|