|

A

North Sea oil and gas drilling and exploration platform

NORTH

SEA OIL PRICE CRASH - GUARDIAN 14 JAN 2015

The potential impact of the oil price slump on Scotland was underlined as a leading energy expert warned on Wednesday that North Sea oilfields could be shut down if the oil price fell by just a few more dollars.

The rising sense of crisis about the plummeting price – which has fallen 60% in the last six months – prompted the Scottish government to promise an emergency taskforce to try to preserve jobs in the offshore energy sector.

Meanwhile, Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England warned that the Scottish economy was heading for a “negative shock”.

The oil industry consultancy Wood Mackenzie said that at the current price for Brent blend, of

$46 a barrel, some UK production was already failing to break even, and further falls could endanger output.

Robert Plummer, a research analyst with the firm, said that at $50 a barrel oil production was costing more than its value in 17 countries, including the US and UK.

Plummer told Scottish Energy News: “Once the oil price reaches these levels producers have a sometimes complex decision to continue producing, losing money on every barrel produced, or to halt production, which will reduce supply.”

Concern about cutbacks was heightened Wednesday when Shell announced it was scrapping a $6.4bn (£4.2bn) energy project in the

Middle East because it was no longer commercial, with oil prices falling to six-year lows.

Plummer said that if oil prices fell to $40, a small but significant part of global supply would become “cash negative”, although some operators would choose to keep producing oil at a loss rather than stop production.

Large companies such as Shell, BP and

Chevron, have already spoken of hundreds of job cuts in Aberdeen amid expectations that overall spending across the industry will be slashed by anywhere up to 30% for the coming year.

Carney told MPs on the Treasury select committee that falling oil prices would deal a blow to the Scottish economy but that the decline would be offset by the boost to the wider British economy due to the falling petrol prices. “It is net positive for the UK economy,” he said. “It is a negative shock to the Scottish economy, which is substantially mitigated … by the nature of the economic union that exists.”

He was asked about an estimate suggesting the price slide could wipe £6bn off Scottish GDP, but he said the bank had not calculated the hit to

Scotland.

Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland’s first minister, outlined plans to set up a new energy jobs taskforce with the aim of maintaining jobs and mitigating the impact of losses.

Speaking on a flying visit to the oil capital of Aberdeen she said: “The recent drop in the price of a barrel of crude oil, combined with the mismanagement of oil and gas fiscal policy by the UK government, and other challenges facing the industry, pose a threat to a number of jobs.

“The North Sea has made an enormous contribution to the Scottish and UK economies over the last 40 years. It is now vital, in order to prolong the life of the industry beyond 2050 and maximise economic benefits, that the UK government maintains the momentum for fiscal and regulatory change in the oil and gas sector.”

The SNP has faced criticism in recent weeks for its failure to respond to the growing crisis in Scotland’s North Sea oil and gas business.

Labour accused SNP ministers of “sitting on their hands” and failing to tackle the impact of plummeting oil prices, which fell to $115 before the summer.

Scottish Labour’s finance spokeswoman, Jackie Baillie, said: “The falling oil price is the biggest threat to jobs in Scotland since [the close of the steel plant at] Ravenscraig, and the Scottish government has been silent on the issue.”

The chancellor, George

Osborne, used the autumn statement last month to cut taxes but the industry has said his initiatives did not go far enough.

Treasury officials have since been asked to work on a wider-ranging package of measures. A recent report for the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills had warned that 35,000 jobs would be at risk over the next five years – and that was largely concluded before the latest oil price slump.

Drilling levels had collapsed in the North Sea even when prices exceeded $100, partly because of rising costs and a hike in taxes by the government three years ago.

With production falling fast over the last 10 years the government requested an industry review by the oil industry figure Sir Ian Wood; it called for a huge shake-up of regulation in the sector.

Shell, in a joint statement with its partner, Qatar Petroleum, about the Ras Laffan petrochemical scheme, said: “The decision came after a careful and thorough evaluation of commercial quotations from EPC [engineering, procurement and construction] bidders, which showed high capital costs rendering it commercially unfeasible, particularly in the current economic climate prevailing in the energy industry.”

The cutbacks in the oil and gas industry are global. Shell also just unveiled plans to slash 300 jobs at its Albian tar sands project in Alberta, while Suncor, another company in Canada, said it would make 1,000 redundancies.

Carney warned on Wednesday of other financial risks linked to the falling oil price. He said it could lead to defaults on debt repayments by emerging market economies, although he refused to name which ones.

He also pointed to risks in the junk bond markets, which fund US shale exploration, reiterating a point made in the Bank of England’s twice yearly update on risks to the financial system published last month.

BP

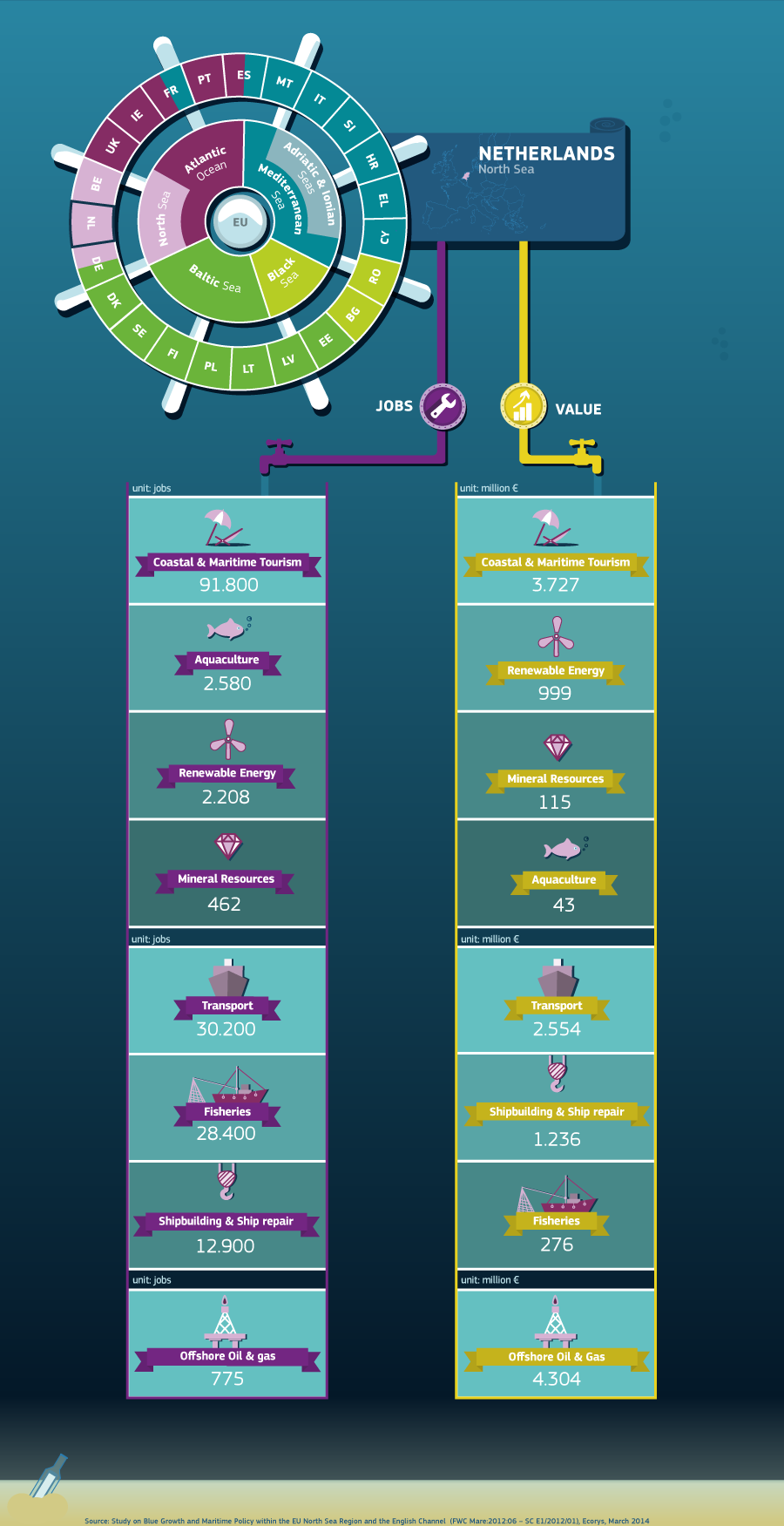

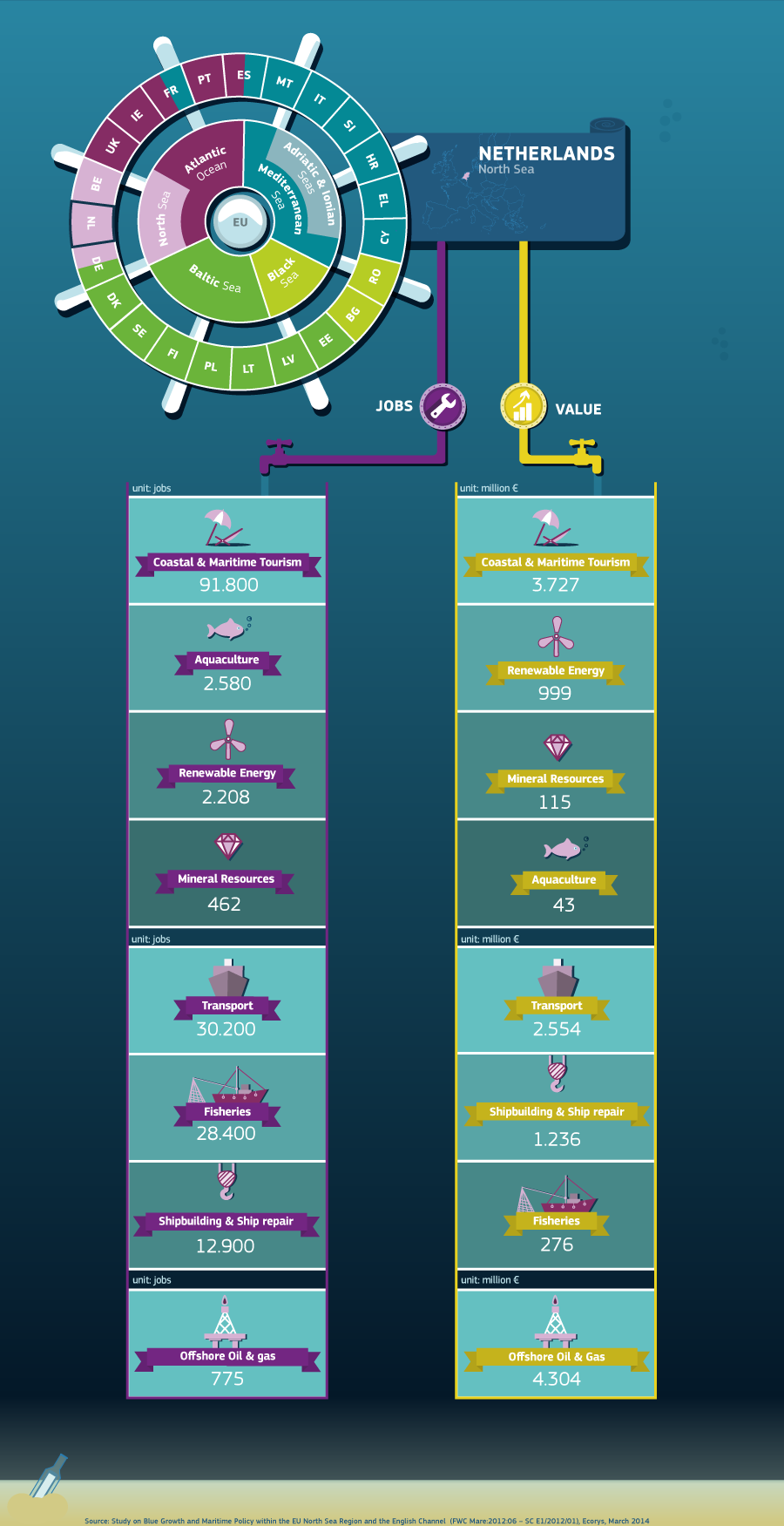

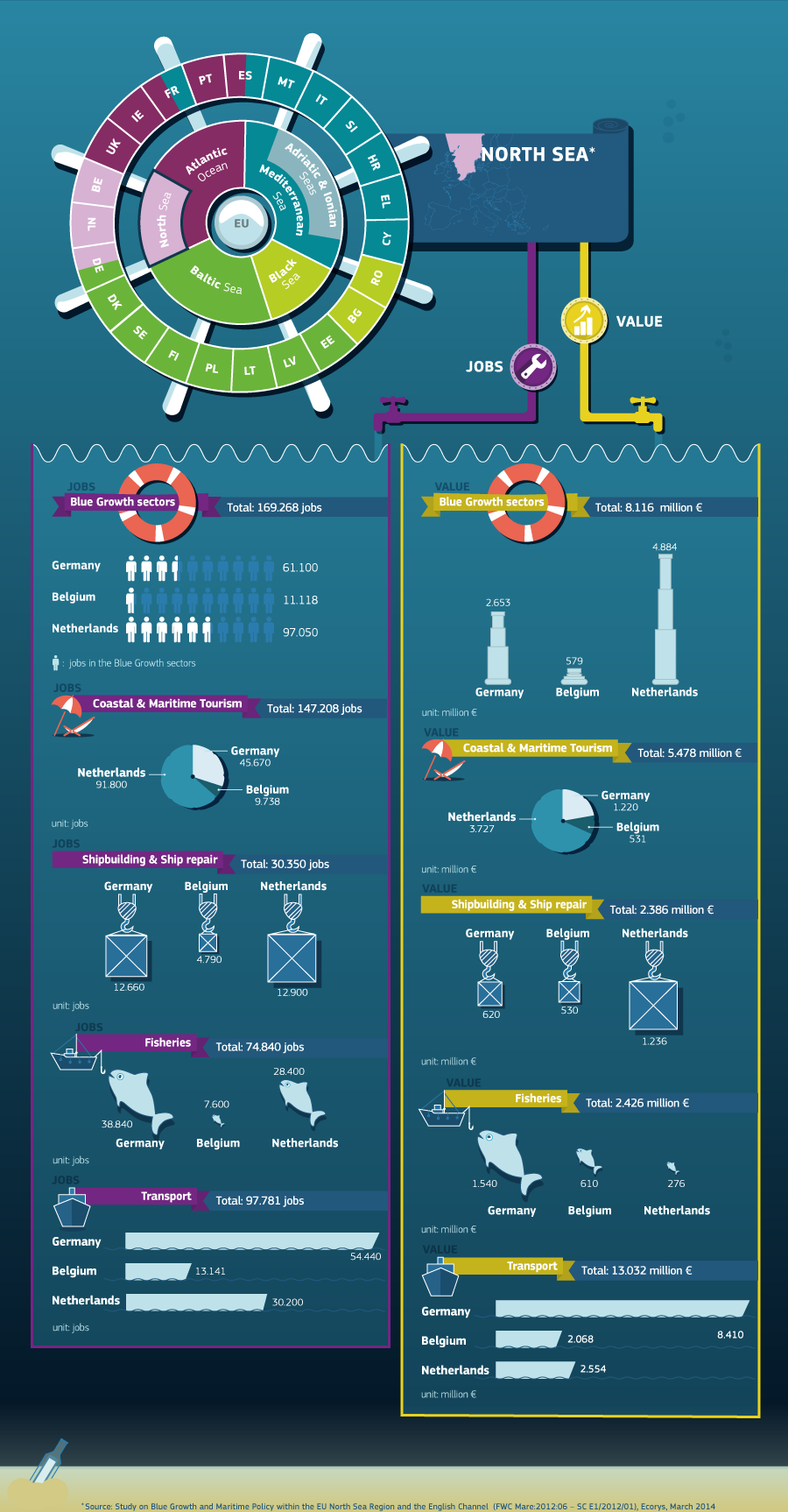

NORTH SEA STATS

*

BP employs 3,500 staff in the North Sea out of a total of 15,000 across the UK and 84,000 across the world.

* To date it has invested £35bn in the North Sea, and produced five billion barrels of oil and gas.

* North Sea operations account for 5% of the company's global production.

* It has 45 production fields, 33 platforms and 10 pipeline systems in the UK continental shelf.

* BP estimates it is sitting on three billion barrels of oil equivalent reserves in the North Sea.

* The Clair field, west of Shetland, is BP's flagship future development and the largest oilfield in Europe, containing an estimated eight billion barrels of oil.

* The company also owns the Forties Pipeline System, described as the single most important piece of oil and gas infrastructure in the UK.

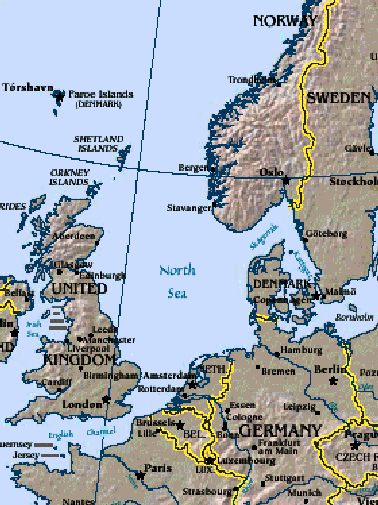

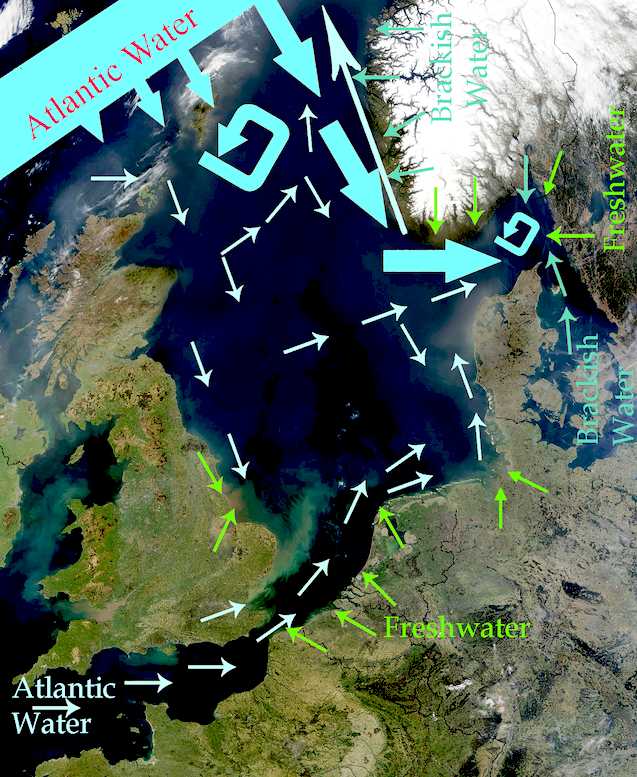

GEOGRAPHY

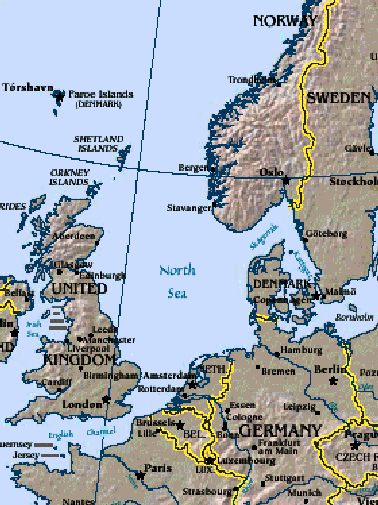

The North Sea is a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean located between Great Britain, Scandinavia,

Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and

France. An epeiric (or "shelf") sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Sea in the north. It is more than 970 kilometres (600 mi) long and 580 kilometres (360 mi) wide, with an area of around 750,000 square kilometres (290,000 sq mi).

The North Sea has long been the site of important European shipping lanes as well as a major fishery. The sea is a popular destination for recreation and tourism in bordering countries and more recently has developed into a rich source of energy resources including fossil fuels, wind, and early efforts in wave power.

Historically, the North Sea has featured prominently in geopolitical and military affairs, particularly in Northern Europe but also globally through the power northern Europeans projected worldwide during much of the Middle Ages and into the modern era. The North Sea was the centre of the Vikings' rise. Subsequently, the Hanseatic League, the Netherlands, and the British each sought to dominate the North Sea and thus the access to the markets and resources of the world. As Germany's only outlet to the ocean, the North Sea continued to be strategically important through both World Wars.

The coast of the North Sea presents a diversity of geological and geographical features. In the north, deep fjords and sheer cliffs mark the Norwegian and Scottish coastlines, whereas in the south it consists primarily of sandy beaches and wide mudflats. Due to the dense population, heavy industrialization, and intense use of the sea and area surrounding it, there have been a number of environmental issues affecting the sea's ecosystems. Environmental concerns — commonly including

over-fishing, industrial and agricultural runoff, dredging, and dumping among others — have led to a number of efforts to prevent degradation of the sea while still making use of its economic potential.

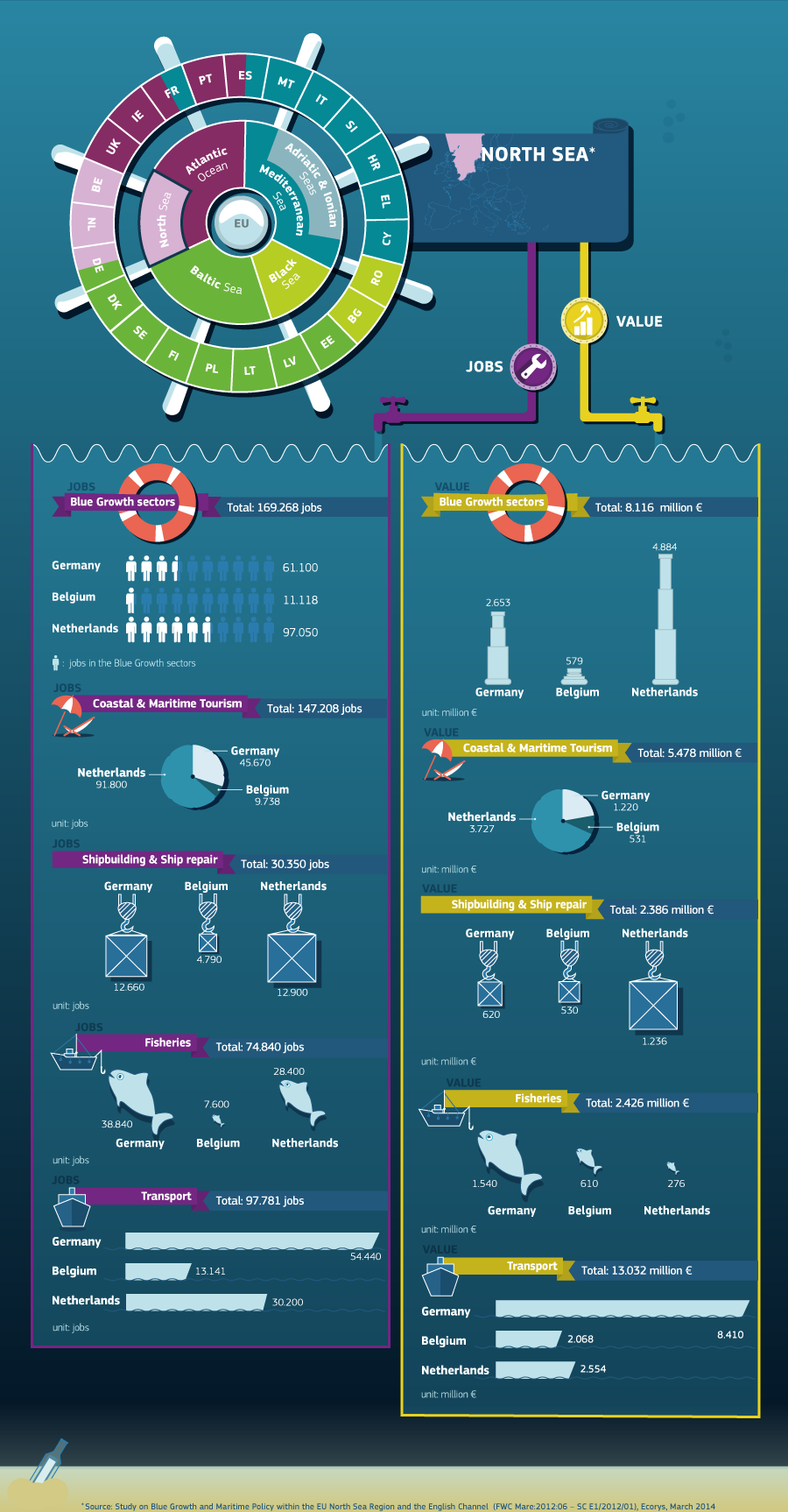

NORTH SEA ECONOMICS

- POLITICAL STATUS

Countries that border the North Sea all claim the 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) of territorial waters, within which they have exclusive fishing

rights. The Common Fisheries Policy of the European Union (EU) exists to coordinate fishing rights and assist with disputes between EU states and the EU border state of Norway.

After the discovery of mineral resources in the North Sea, the Convention on the Continental Shelf established country rights largely divided along the median line. The median line is defined as the line "every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured." The ocean floor border between Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark was only reapportioned after protracted negotiations and a judgement of the International Court of Justice.

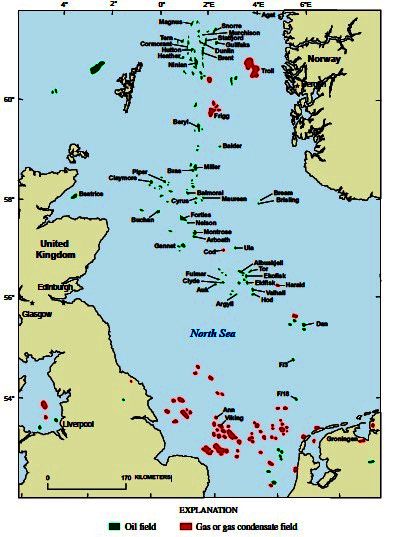

Map

of the North Sea

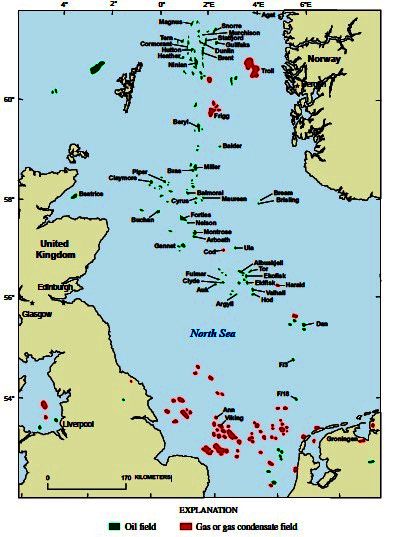

OIL and GAS

In the oil industry, the term "North Sea" often includes areas such as the Norwegian Sea and the area known as "West of Shetland", "the Atlantic Frontier" or "the Atlantic Margin" that is not geographically part of the North Sea.

Brent crude is still used today as a standard benchmark for pricing oil, although the contract now refers to a blend of oils from fields in the northern North Sea.

As early as 1859, oil was discovered in onshore areas around the North Sea and natural gas as early as 1910.

Test drilling began in 1966 and then, in 1969, Phillips Petroleum Company discovered the Ekofisk oil field distinguished by valuable, low-sulphur oil. Commercial exploitation began in 1971 with tankers and, after 1975, by a pipeline, first to Teesside, England and then, after 1977, also to Emden, Germany.

The exploitation of the North Sea oil reserves began just before the 1973 oil crisis, and the climb of international oil prices made the large investments needed for extraction much more attractive.

Although the production costs are relatively high, the quality of the oil, the political stability of the region, and the nearness of important markets in western Europe has made the North Sea an important oil producing region. The largest single humanitarian catastrophe in the North Sea oil industry was the destruction of the offshore oil platform Piper Alpha in 1988 in which 167 people lost their lives.

Besides the Ekofisk oil field, the Statfjord oil field is also notable as it was the cause of the first pipeline to span the Norwegian trench. The largest

natural gas field in the North Sea, Troll gas field, lies in the Norwegian trench dropping over 300 metres (980 ft) requiring the construction of the enormous Troll A platform to access it.

The price of Brent Crude, one of the first types of oil extracted from the North Sea, is used today as a standard price for comparison for crude oil from the rest of the world. The North Sea contains western Europe's largest oil and natural gas reserves and is one of the world's key non-OPEC producing regions.

In the UK sector of the North Sea, the oil industry invested £14.4 billion in 2013, and was on track to spend £13 billion in 2014. Industry body Oil & Gas UK put the decline down to rising costs, lower production, high tax rates, and less exploration.

LICENSING

Following the 1958 Continental shelf convention and after some disputes on the rights to natural resource exploitation the national limits of the exclusive economic zones were ratified. Five countries are involved in oil production in North Sea. All operate a tax and royalty licensing regime. The respective sectors are divided by median lines agreed in the late 1960s:

United Kingdom – The Department of Energy and

Climate Change (DECC – formerly the Department of Trade and Industry) grants licences. The UKCS (United Kingdom Continental Shelf) is divided into quadrants of 1 degree latitude and one degree longitude. Each quadrant is divided into 30 blocks measuring 10 minutes of latitude and 12 minutes of longitude. Some blocks are divided further into part blocks where some areas are relinquished by previous licensees. For example, block 13/24a is located in quad 13 and is the 24th block and is the 'a' part block. The UK government has traditionally issued licences via periodic (now annual) licensing rounds. Blocks are awarded on the basis of the work programme bid by the participants. The UK government has actively solicited new entrants to the UKCS via "promote" licensing rounds with less demanding terms and the fallow acreage initiative, where non-active licences have to be relinquished.

Norway – The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate

(NPD) grants licences. The NCS is also divided into quads of 1 degree by 1 degree. Norwegian licence blocks are larger than British blocks, being 15 minutes of latitude by 20 minutes of longitude (12 blocks in a quad). Like in Britain, there are numerous part blocks formed by re-licensing relinquished areas.

Denmark – The Danish Energy Authority

administers the Danish sector. The Danes also divide their sector of the North Sea into 1 degree by 1 degree quadrants. Their blocks, however, are 10 minutes latitude by 15 minutes longitude. Part blocks exist where partial relinquishments have taken place.

Germany – Germany and the Netherlands share a quadrant and block grid—quadrants are given letters rather than numbers. The blocks are 10 minutes latitude by 20 minutes longitude. Germany has the smallest sector in the North Sea.

Netherlands – The Dutch sector is located in the Southern Gas Basin and shares a grid pattern with Germany.

Geographic

division of the North Sea drilling rights

NORTH

SEA OIL RESERVES

The British and Norwegian sections hold most of the remainder of the large oil reserves. It is estimated that the Norwegian section alone contains 54% of the sea's oil reserves and 45% of its gas reserves. More than half of the North Sea oil reserves have been extracted, according to official sources in both Norway and the UK. For Norway, the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate gives a figure of 4,601 million cubic metres of oil (corresponding to 29 billion barrels) for the Norwegian North Sea alone (excluding smaller reserves in Norwegian Sea and Barents Sea) of which 2,778 million cubic metres (60%) has already been produced prior to January 2007. UK sources give a range of estimates of reserves, but even using the most optimistic "maximum" estimate of ultimate recovery, 76% had been recovered at end 2010. Note the UK figure includes fields which are not in the North Sea (onshore, West of Shetland).

United Kingdom Continental Shelf production was 137 million tonnes of oil and 105 billion m³ of gas in 1999. (1 tonne of crude oil converts to 7.5 barrels). The Danish explorations of Cenozoic stratigraphy, undertaken in the 1990s, showed petroleum rich reserves in the northern Danish sector, especially the Central Graben area. The Dutch area of the North Sea followed through with onshore and offshore gas exploration, and well creation.

Exact figures are debatable, because methods of estimating reserves vary and it is often difficult to forecast future discoveries.

Peaking in 1999, production of North Sea oil was nearly 950,000 m³ (6 million barrels) per day. Natural gas production was nearly 280×109 m³ (10 trillion cubic feet) in 2001 and continues to increase, although British gas production is in sharp decline.

UK oil production has seen two peaks, in the mid 1980s and late 1990s, with a decline to around 300×103 m³ (1.9 million barrels) per day in the early 1990s. Monthly oil production peaked at 13.5×106 m³ (84.9 million barrels) in January 1985 although the highest annual production was seen in 1999, with offshore oil production in that year of 407×106 m³ (398 million barrels) and had declined to 231×106 m³ (220 million barrels) in 2007. This was the largest decrease of any other oil exporting nation in the world, and has led to Britain becoming a net importer of crude for the first time in decades, as recognized by the energy policy of the United Kingdom. The production is expected to fall to one-third of its peak by 2020. Norwegian crude oil production as of 2013 is 1.4 mbpd. This is a more than 50% decline since the peak in 2001 of 3.2 mbpd.

RENEWABLE ENERGY

Due to the strong prevailing winds, countries on the North Sea, particularly Germany and Denmark, have used the shore for wind power since the 1990s. The North Sea is the home of one of the first large-scale offshore wind farms in the world, Horns Rev 1, completed in 2002. Since then many other wind farms have been commissioned in the North Sea (and elsewhere), including the two largest windfarms in the world as of September 2010; Thanet in the UK and Horns Rev 2 in Denmark.

The expansion of offshore wind farms has met with some resistance. Concerns have included shipping collisions and environmental effects on ocean ecology and wildlife such as fish and migratory birds, however, these concerns were found to be negligible in a long-term study in

Denmark released in 2006 and again in a UK government study in 2009. There are also concerns about reliability, and the rising costs of constructing and maintaining offshore wind farms. Despite these, development of North Sea wind power is continuing, with plans for additional wind farms off the coasts of Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. There have also been proposals for a transnational power grid in the North Sea to connect new offshore wind farms.

Energy production from tidal power is still in a pre-commercial stage. The European Marine Energy Centre has installed a wave testing system at Billia Croo on the Orkney mainland and a tidal power testing station on the nearby island of Eday. Since 2003, a prototype Wave Dragon energy converter has been in operation at Nissum Bredning fjord of northern Denmark.

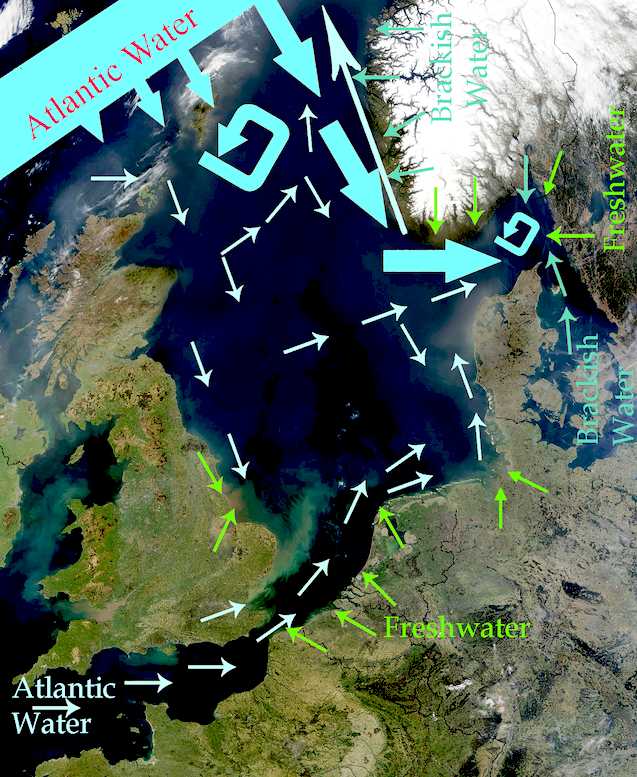

North Sea

currents and weather patterns

NORTH

SEA TIDE RANGES

|

Tidal

range [m]

(from calendars)

|

Maximal tidal

range [m]

|

Tide-gauge

|

Geographical

and historical features

|

|

0.79

– 1.82

|

2,39

|

Lerwick

|

Shetland-Islands

|

|

2.01

– 3.76

|

4,69

|

Aberdeen

|

Mouth

of Dee-River

Dee in Scotland

|

|

2.38

– 4.61

|

5,65

|

North

Shields

|

Mouth

of Tyne-Estuary

|

|

2.31

– 6.04

|

8.20

|

Kingston

upon Hull

|

northern

side of Humber-estuary

|

|

1.75

– 4.33

|

7.14

|

Grimsby

|

southern

side of Humber-estuary

farther seaward

|

|

1.98

– 6.84

|

6.90

|

Skegness

|

Lincolnshire

coast north of the Wash

|

|

1.92

– 6.47

|

7.26

|

King's

Lynn

|

mouth

of Great

Ouse into the

Wash

|

|

2.54

– 7.23

|

|

Hunstanton

|

eastern

egde of the

Wash

|

|

2.34

– 3.70

|

4.47

|

Harwich

|

East

Anglian coast north of Thames

estuary

|

|

4.05

– 6.62

|

7.99

|

London

Bridge

|

inner

end of Thames-estuary

|

|

2.38

– 6.85

|

6.92

|

Dunkerque

(Dunkirk)

|

dune

coast east of the Strait

of Dover

|

|

2.02

– 5.53

|

5.59

|

Zeebrugge

|

dune

coast west of Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt

delta

|

|

3.24

– 4.96

|

6.09

|

Antwerpen

|

inner

end of the southernmost estuary of Rhine-Meuse-Scheldt

delta

|

|

1.48

– 1.90

|

2.35

|

Rotterdam

|

borderline

of estuary delta[39]

and sedimentation delta of the Rhine

|

|

1.10

– 2.03

|

2.52

|

Katwijk

|

mouth

of the Uitwateringskanaal of Oude

Rijn into the sea

|

|

1.15

– 1.72

|

2.15

|

Den

Helder

|

northeastern

end of Holland

dune coast west of IJsselmeer

|

|

1.67

– 2.20

|

2.65

|

Harlingen

|

east

of IJsselmeer,

outlet of IJssel

river, the eastern branch of the Rhine

|

|

1.80

– 2.69

|

3.54

|

Borkum

|

island

in front of Ems river estuary

|

|

2.96

– 3.71

|

|

Emden

|

east

side of Ems

river estuary

|

|

2.60

– 3.76

|

4.90

|

Wilhelmshaven

|

Jade

Bight

|

|

2.66

– 4.01

|

4.74

|

Bremerhaven

|

seaward

end of Weser

estuary

|

|

3.59

– 4.62

|

|

Bremen-Oslebshausen

|

Bremer

Industriehäfen, inner Weser

estuary

|

|

3.3

– 4.0

|

|

Bremen

Weser barrage

|

artificial

tide limit of river Weser, 4 km upstream of the city

centre

|

|

2.6

– 4.0

|

|

Bremerhaven

1879

|

before

onset of Weser

Correction (Weser straightening works)

|

|

0 – 0.3

|

|

Bremen

city centre 1879

|

before

onset of Weser

Correction (Weser straightening works)

|

|

1,45

|

|

Bremen

city centre 1900

|

Große

Weserbrücke, 5 years after completion of Weser

Correction works

|

|

2.54

– 3.48

|

4.63

|

Cuxhaven

|

seaward

end of Elbe

estuary

|

|

3.4

– 3.9

|

4.63

|

Hamburg

St. Pauli

|

St.

Pauli Piers, inner part of Elbe estuary

|

|

1.39

– 2.03

|

2.74

|

Westerland

|

Sylt

island in front of Nordfriesland

coast

|

|

2.8

– 3.4

|

|

Dagebüll

|

coast

of Wadden

Sea in Nordfriesland

|

|

1.1

– 2.1

|

2,17

|

Esbjerg

|

northern

end of Wadden Sea in Denmark

|

|

0.5

– 1.1

|

|

Hvide

Sande

|

Danish

dune coast, entrance of Ringkøbing

Fjord lagoon

|

|

0.3

– 0.5

|

|

Thyborøn

|

Danish

dune coast, entrance of Nissum Bredning lagoon,

part of Limfjord

|

|

0,2

– 0,4

|

|

Hirtshals

|

Skagerrak.

Hanstholm

and Skagen

have the same values.

|

|

0.14

– 0.30

|

26

|

Tregde

|

Skagerrak,

Southern end of Norway, east of an amphidromic

point

|

|

0.25

– 0.60

|

65

|

Stavanger

|

North

of that amphidromic point, rhythm of the tides irregular

|

|

0.64

– 1.20

|

1,61

|

Bergen

|

Rhythm

of the tides regular

|

|

The

North Sea, Four Days Battle

MARINE TRAFFIC

The North Sea is important for marine transport and its shipping lanes are among the busiest in the world. Major ports are located along its coasts: Rotterdam, the busiest port in Europe and the fourth busiest port in the world by tonnage as of 2013, Antwerp (was 16th) and Hamburg (was 27th),

Bremen/Bremerhaven and Felixstowe, both in the top 30 busiest container seaports, as well as the Port of

Bruges-Zeebrugge, Europe's leading RoRo port.

Fishing boats, service boats for offshore industries, sport and pleasure craft, and merchant ships to and from North Sea ports and Baltic ports must share routes on the North Sea. The Dover Strait alone sees more than 400 commercial vessels a day. Because of this volume, navigation in the North Sea can be difficult in high traffic zones, so ports have established elaborate vessel traffic services to monitor and direct ships into and out of port.

The North Sea coasts are home to numerous canals and canal systems to facilitate traffic between and among rivers, artificial

harbours, and the sea. The Kiel Canal, connecting the North Sea with the Baltic Sea, is the most heavily used artificial seaway in the world reporting an average of 89 ships per day not including sporting boats and other small watercraft in 2009. It saves an average of 250 nautical miles (460 km; 290 mi), instead of the voyage around the Jutland Peninsula. The North Sea Canal connects Amsterdam with the North Sea.

The

North Sea taken by a NASA satellite

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC - ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BAY BENGAL - BERING

- CARIBBEAN - CORAL

- EAST CHINA

ENGLISH

CH - GOC

- GULF GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO - INDIAN -

IOC

- IRC

- MEDITERRANEAN - NORTH

SEA - PACIFIC - PERSIAN

GULF

RED

SEA - SEA JAPAN - STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE - UNCLOS

- UNEP

WOC

- WWF

AMAZON

- BURIGANGA - CITARUM - CONGO -

CUYAHOGA - GANGES - IRTYSH -

JORDAN - LENA - MANTANZA-RIACHUELO

MARILAO

- MEKONG - MISSISSIPPI - NIGER - NILE - PARANA - PASIG - SARNO - THAMES

- YANGTZE - YAMUNA - YELLOW

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Wikipedia

North_Sea

Spirit-Dunkirk

spirit as 40 private boats search for British sailors in the Atlantic

after US Coastguard quits

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlantic_Ocean

The

Guardian 2015 January 14 oil price slump could threaten north sea

oilfields BBC

news UK Scotland business Wikipedia

North_Sea_oil http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Sea_oil

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-30817678

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jan/14/oil-price-slump-could-threaten-north-sea-oilfields

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North_Sea

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/10843975/US-coastguard-to-renew-search-for-missing-yachtsmen.html

http://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2014/may/18/four-british-yachtsmen-missing-atlantic?CMP=EMCNEWEML6619I2

http://www.enterprise-europe-scotland.com/sct/news/?newsid=4538

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Convention_for_the_Safety_of_Life_at_Sea

FICTION

Operation

Neptune - An

advanced nuclear submarine is hijacked by environmental extremists intent on

stopping pollution from the burning of fossil fuels. The extremists torpedo a

number of oil wells as part of a campaign to cause energy chaos, with bigger

plans to come. If you enjoyed

Battleship,

Under Siege or

The Hunt for Red

October, this is a

must for you.

|