|

|

WHALE SHARKS

|

|

|

|

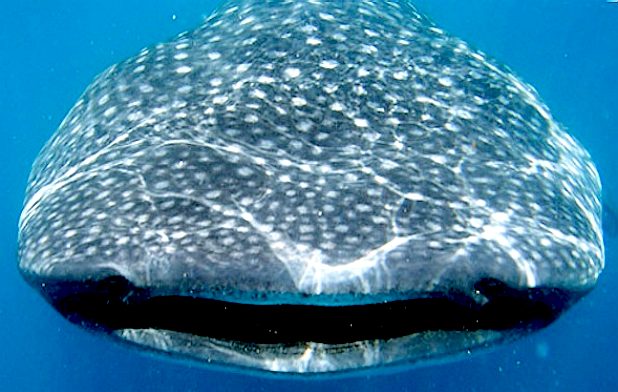

Proof, if that was ever needed, that life evolves from different angles to fill the same ecological niche, is the whale shark. Mammals are the largest filter feeders, yet their breathing system is less well adapted to the ocean environment than the gills of a true aquatic like the whale shark. And yet the whale shark, even though feeding on the same food, has not yet reached the size of a blue whale, as an indicator that the breathing with lungs is more efficient - even though tying whales proper to the surface.

The whale shark is found in tropical and warm oceans and lives in the open sea, with a lifespan of about 70 years. Whale sharks have very large mouths, and as filter feeders, they feed mainly on plankton. The BBC program Planet Earth filmed a whale shark feeding on a school of small fish. The same documentary showed footage of a whale shark timing its arrival to coincide with the mass spawning of fish shoals and feeding on the resultant clouds of eggs and sperm.

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is a slow-moving filter feeding shark and the largest known extant fish species. The largest confirmed individual had a length of 12.65 m (41.50 ft) and a weight of more than 21.5 metric tons (47,000 lb), and unconfirmed reports of considerably larger whale sharks exist. Claims of individuals over 14 m (46 ft) long and weighing at least 30 mt (66,000 lb) are not uncommon. The whale shark holds many records for sheer size in the animal kingdom, most notably being by far the largest living nonmammalian vertebrate. It is the sole member of the genus Rhincodon and the family, Rhincodontidae (called Rhiniodon and Rhinodontidae before 1984), which belongs to the subclass Elasmobranchii in the class Chondrichthyes. The species originated about 60 million years ago.

The species was distinguished in April 1828 after the harpooning of a 4.6-m-long specimen in Table Bay, South Africa. Andrew Smith, a military doctor associated with British troops stationed in Cape Town, described it the following year. The name "whale shark" comes from the fish's size, being as large as some species of whales and also that it is filter feeder like baleen whales.

HUMANS & WHALE SHARKS

REPRODUCTION

On 7 March 2009, marine scientists in the Philippines discovered what is believed to be the smallest living specimen of the whale shark. The young shark, measuring only 38 cm (15 in), was found with its tail tied to a stake at a beach in Pilar, Philippines, and was released into the wild. Based on this discovery, some scientists no longer believe this area is just a feeding ground; this site may be a birthing ground, as well. Both young whale sharks and pregnant females have been seen in the waters of Saint Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean, where numerous whale sharks can be spotted during the summer.

CONSERVATION

DAILY MAIL WHALE SHARKS CAUGHT IN FISHING NETS, DECEMBER 2014

These pictures capture the incredible moment when two whale sharks trapped inside a fishing net were set free.

The amazing images

(see more on the Daily Mail website) show divers Chris Rohner and Clare Prebble helping free the tangled pair - which then swim alongside them to say thanks.

Simon, from New

Zealand is quoted as saying: 'The main conservation challenge there is conflict between fishermen and sharks.'

STATISTICS

DISTRIBUTION

Although typically seen offshore,

whale sharks have been found closer to land, entering lagoons or coral atolls, and near the mouths of estuaries and rivers. Its range is generally restricted to about 30° latitude. It is capable of diving to depths of at least 1,286 m (4,219 ft), and is migratory. On 7 February 2012, a large whale shark was found floating 150 kilometres (93 mi) off the coast of Karachi, Pakistan. The length of the specimen was said to be between 11 and 12 m (36 and 39 ft), with a weight of around 15,000 kg (33,000 lb).

Chapter 28 - SHARK ATTACK 1640 E, 80 N (extract from: The $Billion Dollar Whale by Jameson Hunter © 2014)

Visibility

was excellent and the sea was state three on the Beaufort scale – just a

light breeze for hardened mariners. The sun was readying to settle after a

glorious day’s sailing, sinking slowly into the horizon. The Elizabeth

Swan had covered 150 nautical miles since sun up, cruising fast at 18.75 knots,

her low drag hull cutting through the deep blue Pacific water with

consummate ease.

“Skipper,”

said Dan, over the tannoy, “according to the log, we’ve covered 2,000

miles since leaving Honolulu Harbour.” “Great,

that’s “Navigator

to Starlight, come back Starlight.” …… Silence and some crackles….. “Navigator

to Starlight, over.” Silence…. “Dan, switch to autopilot and take her down to 5 knots on batteries. Oh, and lift the boom manually - when the sun disappears. Cheers.” The

radio crackled into life. “Hello John, this is Starlight, caught any good

fish?” “Hi

Sarah. Just heard the race update, thought we’d offer our congratulations

- well done. Over.” “Never

mind that, how’s the search going? Over.” “Not

a jot, keep in touch. Over.” “Okay

big boy, we’re all thinking of you. Mum’s the word, out.” Dan

was keeping a sharp lookout from the Com, while John scoured the horizon

with renewed vigour through powerful Karl Zeiss binoculars, straining for

every last detail which might resemble a whale. After

another 20 minutes John blasted, “Dan, you still awake?” “Yuuup,”

he said involuntarily snapping back to attention, “but this chair sure is

comfy, any chance of a brew?” John

smiled to himself. He was feeling slightly jaded also and the chairs upfront

were exceptionally comfortable. “Okay, I’ll sort some liquid. You keep

at it.” John

hung his spyglasses up and deftly swung into the cabin below. After a

whirlwind galley brew, for which he was famous, he delivered a cup to Dan.

“Offf,” he sighed, collapsing into the soft white leather chair next to

Dan. John took two sips then sat upright again. He focused on the

instruments for a moment. Nothing was showing. “We

won’t find anything chatting,” he said suddenly, and with that he spun

himself out of the chair and off he strode to the aft helm. Coffee

mug firmly located in a gimballed holder and spyglasses snugly pressed

against his brows, John scanned left and right, then right and left. He

checked the compass bearing – west, south west.

“Dan,

any thoughts on position? We should have sighted the whale long ago by my

reckoning.” “It’s

the old needle in the haystack problem. It’s a large ocean Skip.” John

climbed onto the solar decking for a better angle. The light was just

perfect for spotting unusual surface activity on the horizon. There was a

dark patch to the left. “Dan,

look on the sonar, steer 15 degrees to port.” John

strained hard, looking at the small patch which was now dead ahead and

closing to 1200 metres. He swore he could see the patch moving and rubbed

his eyes. His skin prickled. Dan came over the tannoy. “John, this is weird, the sonar shows

several small blips.” Both men were now straining for detail. Two intense

minutes ticked by. “700

metres and closing.” Another

minute passed. “400

metres.” John could now see movement on the surface, the unmistakable darting of shark fins, circling the dark patch. An icy shudder passed through him. The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is one of the most beautifully adapted predators in the ocean with a kill rate of some 50%. It is the most efficient and most feared big fish. They can smell blood in the water at just one part in a million. They’ve been swimming the oceans for millions of years virtually unchanged, their streamlined shape near perfection. They migrate across the oceans for up to 7,000 kilometres, to take advantage of known food sources, such as seals. With an impressive 70% of muscle, special drag reducing scales and a heat exchange conservation system that allows them to keep their blood 140 warmer than other sharks, they can attack prey at phenomenal speeds for short duration. An

array of electrical sensors around their open mouths enables the white shark

to see the electrical fields around their prey, with their eyes shut. They

have rows of triangular razor sharp serrated teeth, which allow them to saw

through their food, by shaking their heads violently from side to side,

notoriously depicted in the film Jaws in the opening sequence. Also known as

white death, the great white is the most dangerous to man. The Pacific Ocean

is full of these roving predators on the lookout for their next meal.

Humpback whales are among the most intelligent of creatures, hunted illegally by certain countries to near extinction, they inspired Jameson Hunter to pen his story about one whale and an adventurer that were bound together on a course with destiny. Sydney harbour is the location for chapter 4 (order may be subject to editorial revision).

The

wounded humpback had laid a trail in the water betraying its course; the

smell of blood in the water had drawn several great whites from miles around

to the possibility of an easy meal. It

looked as though the only reason the sharks hesitated was that the whale was still obviously

mobile and a well aimed blow from its huge flippers, was potentially dangerous.

They kept their distance looking for the right moment to strike. Time was on

their side, or so the sharks thought. “Dan,

action stations, come aft quickly. Sharks! We might be too late.” Dan

ran along the walkway his deck shoes screeching from the acceleration, then

through the aft module. They were just 300 metres away. Dan took the helm. “Great,”

said John. “200

metres skip and look at all those great whites and the size of that

humpback. It’s huge,” gasped Dan. Four

sharks now circled the humpback whale, another having joined the pack. John rigged up the rear searchlights –

the light was fading. What now, he

thought. John lifted up a seat locker taking out his diving suit and hoped

for inspiration. “Bring

us alongside.” Dan

reduced revolutions, stopped engines and reversed thrust, while swinging the

Navigator skillfully ahead of the whale to port. Blood was in the water. Dan

looked back to see John

suiting up for a dive. “Dan,

make us a big brew and get me a feed from our sound system, with plenty of

cable. The whale’s bleeding badly.” “Done

skip.” John

pulled out a loud-hailer. Hmmm,

… “Okay,

Dan, can you dig out some whale song recordings – old chum.” “Tough

call skip, I’ll try,” came the reply. “Wait a minute, we got some in

Hawaii, didn’t we.” John winked to signify his shipmates catch-up. John

rummaged around for a bin liner or inflatable bed, but instead found an old

Harrods carrier bag. It was nice, thick, quality plastic. That’ll

do. He ducked into the galley and came out with two chocolate Mars bars,

which he tucked into his dive pockets. “Dan.”

John

continued to suit up, slung a single cylinder dive pack on his back and

wetted his mask. “Dan,

the sharks are getting kinda hungry.” John

pulled a spear gun from another seat locker, along with six spears, which he

clipped onto his backpack. Dan came out with a coiled cable. “Here

skip, tie these on.” He

rushed back inside. John bared the cable ends and pried the back cover from

the loud-hailer, pulling the wires from the speaker coil carefully. He

twisted the new cable ends to the coil one at a time, then went back into

the locker for some insulating tape and a reel of gaffer tape. Then he taped

the wires to insulate them, and stretched the Harrods bag over the speaker

end, winding the rim with the gaffer tape several times, and tearing the tape

with his teeth. Classical music suddenly drifted up from the galley

speakers, followed by singing whales. “Ready

when you are skip.” John

had already lifted the deck hatch and was half way down the three meters of

steps to the diving platform, when Dan’s face appeared in the hatch frame.

“Get

ready to turn up the music Dan.” “Okay,

should I record on the underwater cams.” “Why

not. Warn me if the sharks get too close,” smirked John. They

both looked across to the circling sharks. John put the megaphone into the

water while still hanging from the boarding rungs. He squeezed the trigger

switch sending a piercing stream of audio beneath the waves. The sharks

began swimming erratically almost immediately, describing a wider circle as if looking away

from the injured whale for other whales, yet still drawn to the smell of blood. The songs

continued playing disorienting the sharks, at the same time the whale began

to move energetically. John entered the water spear-gun in hand. This was going to be dangerous, he thought, as he went under. Now he

could hear the singing. One inquisitive shark headed straight toward him. “Look

out Skip,” said Dan through the loudhailer. John

braced himself, head to head with a great white before bunk time was not his

idea of fun. He pointed the spear-gun at the shark without flinching, ready

to fire if need be. The

shark came straight for him mouth closed but veered off at the last minute,

rubbing his sandpaper like scales against the sharp tip of the spear, which

drew blood from the shark and must have hurt. Dan

turned the volume up full blast, which seemed to send three of the great

whites swimming off in different directions. More agitated than before, the

injured shark again swum for John, this time mouth wide open and head back

in that famous toothy grin, revealing the full magnificence of the rows of

deadly triangular serrated teeth. John fired a warning shot which the shark

felt with its mouth sensors and took evasive action. John was loath to harm

even a shark, if unnecessary. He quickly reloaded and braced himself for

another pass. Dan

was watching in disbelief. He’d seen quite a few TV documentaries about

shark attacks, but never imagined he’d witness a close encounter first

hand. John leapt out of the water in a surge of white froth. “Dan

can you hear me?” “Yo

skip.” “I

grazed that first one. That was too close for comfort. I’m gonna take a

look at the whale’s wound. Can you grab

all our medical supplies and put them on the galley table.” “Going

in again now? You must be crazy” “Got

no choice.” “Okay

skippa.” Dan still thought he was crazy. He had visions of John being

bitten in two, followed by a feeding frenzy. He was seriously worried,

almost in shock himself. Adrenaline coursed through his body. He wondered

what John must be experiencing. Dan climbed down and handed

John a thermal mug, keeping a watchful eye on the sea, as he did so he

remembered that the blood from a great white frightens other sharks away,

including great whites. “Cheers bud,” said John taking a few gulps of hot fluid, then headed back into the water. Keeping a weather eye open for return of any triangular toothed opportunists, John swam over to the whale, somewhat wary in case the animal decided that he was unwelcome. The whale had stopped its agitated movement, as it watched the great whites swim off, noting the bravery of the human with strange twin flippers and metal cylinder on its back that breathed noisily at regular intervals. John swam, around the magnificent creature, looking for signs of injury, and there was some grazing down one side of its body. The

whale was tangled in a mass of fishing gear, ropes and nets. They'd not

noticed that before because most of it was submerged. Then he spotted the slice wound just

behind the whales spout, before its dorsal fin. It was a serious looking

gash about a meter in length, where the harpoon had glanced off, slicing

through about 600 millimetres of flesh as it went. Blood was escaping at

quite a rate. You were lucky my beauty, thought John to himself.

Modern harpoons explode once embedded, thanks to Sven Foyn, a Norwegian whaling captain, who invented these lethal weapons in 1864. If the harpoon had found its target and exploded, this whale would now be sushi. The back wound was bad enough, but the fishing nets had the potential to do far more damage, tiring the whale out and reducing transit efficiency. Hundreds of whales, seals, turtles and even sharks drown each year from discarded fishing gear. John had known about this problem but not seen it for himself. The sudden impact of the problem made his blood boil. He imagined how awful an intelligent creature like a whale must feel once entangled and helpless. John took out his knife and began cutting the fishing net from the whale. Working slowly so as not to distress the animal more than necessary he worked his way back to the tail, almost getting himself caught up more than once. He mused to himself, it was that easy to fall foul of these floating traps. That's fine for a diver with a sharp knife. For a helpless animal with flippers, it is like a hangman waiting around every corner. As each section of the net was cut away John patted the whale, speaking to it. "There, there. Not long now." As each rope was cut off John felt as though he was almost freeing himself, it was a challenge. The whale could feel the ropes falling away and moved its body in appreciation, pushing against John and forcing him sideways at quite a rate. "Good whale, stay still now." He waited for the animal to stop moving before resuming the rescue. He didn't mind the fidgeting, he'd probably do the same. The whale must have read his thoughts, stopping to allow the remaining ropes to be cut away. It knew this was a rescue and John sensed that it knew. So John worked even harder, trying to suppress his excitement and remain focused. The ropes and nets were coming away in larger sections until finally they were gone. The whale felt this also and gave out a loud below: whoooh oooohhhhaaaa. That made John laugh out loud into his mask. Then the whale cleared its throat with a huge breath and spout of water, like a small fireworks display - and thrashed its tail. John swam back along the whales body, until ahead of a giant mottled white flipper, which he held gently for a moment expecting a backlash that never came, then John propelled himself forward meeting with the whale's left eye. The eye seemed to follow him, blinking twice. John sensed the animal studying him appreciatively. He looked deep into the dark blue retina and the whale looked back into John’s hazel eyes. John put both hands around the whale’s eye and smiled. He wasn’t sure the whale could focus this close up, but it signaled back with a deep oooohh aahhh eeee, the vibrations of which went right through John's body. Some people believe that whales can communicate telepathically and some humans have the ability to put animals at ease. Whatever it was, John instinctively hummed back, mimicking the whale’s signal. The intelligent creature flapped its tail softly. The pair had made contact, an understanding of sorts. John surfaced again. He knew he’d have to make some kind of temporary bandage to stem the blood loss. He quickly climbed up the Navigator’s lowered diving platform, going into the galley. “There’s a gash about a metre long, we’ll have to make a makeshift bandage, then try to get some professional help.” Dan nodded. “The sharks have bunked off. I think the blood from the one you wounded did the trick.” “Of course,” replied John. "You should have seen the nets. No wonder the sharks were waiting. Another day and the whale would have drowned anyway. No risk to them then." John pulled off several one and a half meter strips of an especially sticky reinforced general purpose tape, which came in reels 200mm wide for emergency hull repairs. He lapped one over the other at the edges by about 50mm, until he’d achieved a width of some 400mm. He repeated this making two bandages. Then he rummaged about in the cupboards, coming out with a roll of greaseproof paper, which he unrolled over the upward facing adhesive patch, tore off, then rolled up the patch, securing it temporarily with an elastic band that was handy in a draw. “Nice one skip.” John winked back. “What antibiotics have we got,” said John hopefully. “You must be joking, Dan replied.” Both men were now thinking hard. They carried a medical chest, but on this scale, nothing was suitable. Two rolls of lint were then unfolded and two tubes of Germoline squeezed onto one surface, then the other lint strip laid over the top to make a soft cream sandwich. This too was rolled up. "Okay, that's the bandages but they will soon come adrift. We need a sheet and some rope." John looked at Dan for feedback. None came. Instead, Dan went forward and pulled up his bunk. John following Dan's lead rummaged in a storage locker for some thin coiled rope. The two men met with a smile in the rear cockpit, Dan brandishing a sheet and John some rope. There was no need to speak. John began reeling out the rope. "What do you think, 6 meter lengths." "Plenty." replied Dan. John cut four lengths, which Dan tied to each corner of his sheet. They then folded the sheet neatly and wound the rope ends around it. “I need a bag with a strap,” said John raising his eyebrows. Dan went into his cabin and came back with a large nylon fabric computer case covered in bright graphics, still emptying the pockets of accessories. It had a long strap. “That’ll do, ta.” "The sacrifices I’ve made for this project.” He was only joking. “Thanks Dan, I’ll make it up to you.” “Don’t be daft,” said Dan grinning, “anything to help a whale in distress.” But John knew Dan was fond of this case. He adjusted the strap to full length and put it over his left shoulder. Then he put the rolled up sheet into the base, and the two bandage rolls on top, which just accommodated the first aid adequately. “Keep a sharp lookout will you - just in case,” said John, checking his air contents gauge, as he exited the galley and disappeared down the platform steps, stopping for a few seconds for a scan of the horizon to check the ocean for danger, before jumping into the briny. Even though he knew about the shark blood theory, one can’t be too careful. The bubbles dissipated as John surfaced and headed to the whale, now floating still on the surface, sucking air and exhaling noisily every now and then. John duck dived to the left eye, again making visual contact for about twenty seconds. He pointed to the bag, holding it up, as if asking for permission to proceed, then pointed to the whale’s back. The whale breathed noisily like a patient in a hospital that knew treatment would hurt, but making no effort to stop John. He took his chances laughing inwardly at the sounds coming from the animal. He flippered up to the whales fin and climbed onto it, then carefully pulled himself onto the whales back well behind the hemorrhaging gash, using the fin as a step. The whale remained immobile, which he took as a sign that it was safe to proceed. The wound looked angry and painful, though it was a clean cut, it was still bleeding profusely, which made him shudder. He had no time to check the wound. John took out the first rolled up bandage and laid it out sticky side up for size. It covered the full length of the injury with about twenty centimeters on either side. Two bandages overlapping would be only just wide enough. He flipped the bandage and applied it to one side of the wound, at which point the whale let out a wail of pain and thrashed its tail and flippers. “Steady boy.” John patted the whale making soothing noises. Without hesitation he then unrolled the second bandaged and applied it quickly, just in case the whale turned. Once again the whale let out a low groan, then as the soothing cream got to work, it stopped its movements and trumpeted an involuntary sigh. John gently smoothed the overlap and edges, talking all the while to reassure the lone animal he meant no harm. These gestures might have seemed insignificant but the end result was that the whale had decided that this human was a friend. Now came the tricky part, John pulled out the rolled up sheet and uncoiled the rope ends. He laid the sheet over the center of the bandaged wound and unrolled it to left and to right until two rope ends dangled down on either side of the whale. He then dived into the sea and grabbed the ropes on one side, swimming to meet the two ropes dangling on the other side. He then looped the ropes together under the whales throat to make a knot, pulling as hard as he dared without distressing the whale. "Hold in there buddy," said John to the whale as he again climbed the whale's flipper to check the sheet had not slipped. He gently scrambled onto the whales back. Miraculously, the sheet had stayed in place over the bandage, making it look secure - but for how long. It looked for all the world like the whale was wearing a scarf. John dismounted and swam back down to the whale’s eye and waved. He then grasped the huge white and grey patterned flipper in both hands and rubbed it, which was the closest he could come to shaking hands. The whale seemed to respond with a short but tuneful blast, then groaned again long and wistfully. John knew the whale was not well. They needed an expert and quickly.

Blueplanet Universal Holdings Ltd., invites scriptwriters to use the Kulo Luna story as the basis for script submissions. Please email bluefish@bluebird-electric.net for confirmation of permission to use the names and characters in the novel.

UN BANS JAPAN FROM ANTARCTIC WHALING - MARCH 2014

The

UN's International Court of Justice

(ICJ) has ruled that the Japanese government must halt its whaling program in the

Antarctic. It finally agreed with

Australia, which had presented the case in May 2010. Australia’s case claimed that the Japanese whaling program was not for scientific research as claimed by Tokyo, arguing that the program was commercial whaling in disguise. A score of other countries have condemned Japan for the practice, yet it took 4 years for UN’s ICJ to pass its verdict.

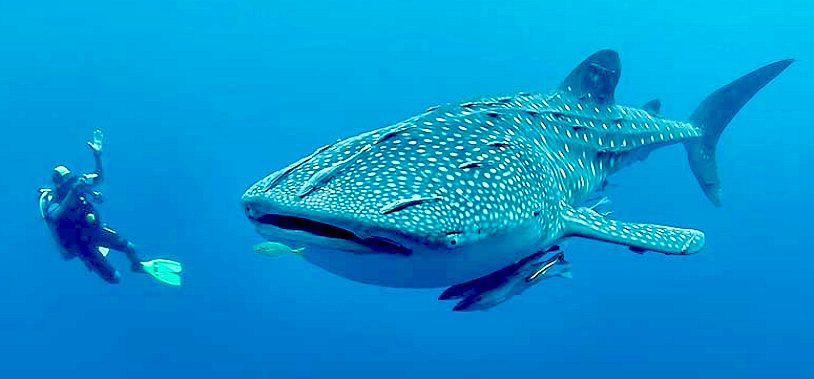

Whale sharks tolerate divers, but will occasionally bump into a careless swimmer.

LINKS & REFERENCE

National Geographic fish whale shark Daily-Mail-news-whale-sharks-trapped-inside-fisherman-nets-set-free-divers-swim-alongside-say-thanks http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whale_shark http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/whale-shark/ tattoos fansshare.com sectasaur_antarctic_melt_john_storm_adventure_book_by_jameson_hunter http://news.seadiscovery.com/post/2014/03/31/UN-Bans-Japan-from-Antarctic-Whaling.aspx

ACIDIFICATION - ADRIATIC - ARCTIC - ATLANTIC - BALTIC - BERING - CARIBBEAN - CORAL - EAST CHINA ENGLISH CH - GOC- GULF MEXICO - INDIAN - MEDITERRANEAN - NORTH SEA - PACIFIC - PERSIAN GULF - SEA JAPAN STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE

- UNEP

|

|||

|

This website is Copyright © 2015 Bluebird Marine Systems Limited. The names Bluebird, Bluefish, SeaNet™, SeaVax™ and the blue bird and fish n flight logo are trademarks. All other trademarks are hereby acknowledged.

|

|||