|

Rio

de Janeiro as seen from Guanabara Bay

THE

GUARDIAN 1 FEBRUARY 2016 - FUNDING PREVENTS POLLUTED WATERWAY CLEANUP

A

consortium of Dutch government, NGOs and businesses has proposed solutions

to Guanabara Bay’s pollution. But cash-strapped Brazil can’t pay.

With the Olympic

Games just months away, Rio

de Janeiro has a problem: rubbish. Hundreds of tonnes of unprocessed

waste flow into the Guanabara Bay every year. The problem isn’t new but

the prospect of Olympic swimmers and sailors taking to Rio’s

contaminated waters have put the issue in the spotlight.

Previous promises from Rio officials to “regenerate Rio’s magnificent

waterways” through investment in sanitation have not delivered results.

Could the Dutch environment ministry have better luck? In an ambitious and

diplomatically unorthodox move it has pulled together some of the country’s

leading waste experts, including businesses and NGOs, to propose a variety

of innovative solutions under the name Clean

Urban Delta Initiative.

“Guanabara Bay is so polluted that we need all hands on deck to solve

this sooner rather than later,” says Yvon Wolthuis, a sustainability

expert and co-developer of the Clean Urban Delta Initiative. “Plus,

there’s so much happening in an urban bay environment like Rio that you

can’t just rely on one governance model or technology to fix it.”

The initiative has backing from the World Bank and the Dutch Development

Bank and aims to showcase Dutch

water management expertise. It lays out 20 separate proposals to deal with

Guanabara Bay’s water pollution and solid waste challenges.

The list of proposed solutions ranges from installing temporary water

treatment plants and purifying water via “constructed wetlands” to

creating carpets from recovered nylon fishing nets. The ideas put forward

by the consortium are intended to be low-cost, high impact and quick to

implement, says Wolthius.

One of these proposed solutions is a project to help Rio’s litter

pickers get more value from plastic waste. Based on a collaboration

between a group of local designers, environmental charity WWF and the

non-profit Plastic Soup

Foundation, the project revolves around a low-cost plastic shredder

and moulding machine that waste pickers can use to make recyclable

products like plastic statues.

An initial pilot is planned in a favela community on the Carioca River,

close to the city’s iconic Christ the Redeemer statue. Daniël Poolen

(nicknamed the “Eco Prof” thanks to a science show he presents on

Dutch TV) is one of the driving forces behind the project. “Thousands of

tourists climb up the hill beside this community every day,” says Poolen,

“if the waste pickers can shred and mould the plastics they usually sell

on, they can earn ten or twenty times what they earn now.”

He concedes that the Carioca River is only one of about 18 garbage-choked

rivers that feed into Guanabara Bay. However, if local people see that

money can be made by recycling plastic that would otherwise end up in the

river, then they will be incentivized to do the same along Rio’s other

river tributaries too, he says.

The

problem is money. The price-tag for the litter picker scheme – which

also includes an eco-trail along the Carioca River, with local people

offering paid tours, and the renovation of Rio’s key water basins – is

about 4m real (£700,000). Yet Brazil is suffering its worst recession for

decades and Rio’s state government, which is responsible for the

Guanabara Bay’s clean-up, is struggling. As a result, the Plastic

Soup Foundation is having to search out private funds to get the project

off the ground.

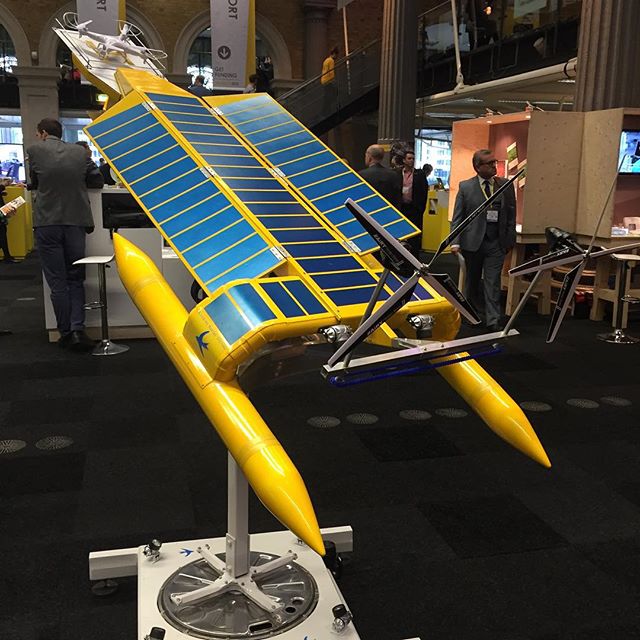

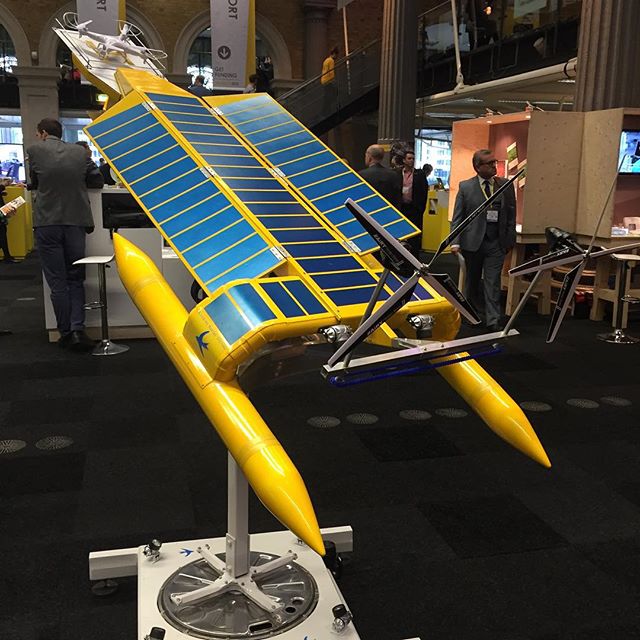

Dutch dredging company Royal IHC,

a member of the consortium, has run into a similar barrier. It has

developed a low-cost, versatile vessel specifically designed for urban bay

areas such as Guanabara. The catamaran-style “waste harvester” uses a

system of interchangeable barges and on-board storage to continuously

harvest surface waste without having to frequently return to shore to

unload.

“We hoped that Rio would be a good case study to pilot this new

technology, but the funding isn’t there”, says company spokersperson

Marjolein van Noort.

Another consortium member, Dutch engineering consultancy firm Tauw,

experienced similar difficulties. Its solution is based on the

construction of small polypropylene tubes on the riverbed and a permeable

grid above that catch and store floating rubbish. Despite interest from

the Rio state government, the funding to install the firm’s “eco-barrier”

wasn’t forthcoming.

Henry Raben, head of site development at Tauw, estimates that installing

the system on the six most polluted rivers feeding into the bay would cost

about £4.6m. “But the clock is now running. To be ready for the

Olympics, we’d ideally have installed the geotubes about six months ago.”

Brazil is a “very complex” market, says Wolthuis, who takes heart from

the fact that the Dutch consortium’s package of solutions offers a

template for clean-up efforts in other polluted deltas around the world.

“Our focus has been on Rio, but these ideas could just as easily be

applied to Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City, Jakarta or Abidjan. None of these

urban delta areas are currently addressing their waste problems from a

joined-up, holistic point of view,” she argues. By

Oliver

Balch

OLYMPIC

GAMES FIRST TEST - Athletes of the Finn class compete during the first

test event for the Rio 2016 Olympic Games at the Guanabara Bay in Rio de

Janeiro, Brazil. A drug-resistant “super bacteria” that’s normally

found in hospitals has been discovered in the waters. With some 70 percent

of sewage in this city of 12 million going untreated -- and flowing, raw,

into rivers, onto beaches and into the Guanabara Bay - water quality has

been a major worry ahead of the 2016 summer games. In their Olympic bid,

organizers pledged to slash by 80 percent the amount of sewage and garbage

that's pumped into the bay daily, but critics insist little has been done.

Water quality tests still show sky-high levels of fecal matter throughout

much of the bay, and authorities have a near-blanket standing

recommendation against swimming on any of its beaches. Flamengo beach,

where the super bacteria was discovered, is among the Guanabara Bay

beaches considered unfit for swimming.

Few athletes of any nationality care to dwell on the subject. They're trained to play the schedule and focus on what they can control. There are exceptions, such as Martine Grael, who

is quoted as saying that she has hauled discarded television sets out of the water during training sessions, and Dutch windsurfer Dorian van Rijsselberghe, the defending Olympic champion. An ambassador for the Netherlands-based nonprofit Plastic Soup Foundation, van Rijsselberghe called the conditions in Rio "disgustingly filthy and dangerous" in a blog written after he won the Copa Brasil de Vela event in Guanabara Bay in December:

"A member of our coaching staff almost puked while entering the Olympic harbor," van Rijsselberghe wrote in text translated and posted on the foundation's website.

"Raw sewage. The athletes do not talk about it. ... They are not there to challenge the world's environmental issues. But the athletes are all concerned and deeply worried.

"I am happy I won last week. Maybe I won because I had the least amount of debris on my fin."

The contrast between Rio's topographic beauty and the horrors in its waters shocked van Rijsselberghe in his first race there in 2013. "We had to slalom through the water to avoid plastic garden chairs, a refrigerator, [dead] animals," he says in a phone interview. He saw fewer large floating objects this time and knows of no Dutch athlete who got sick, but he is still disturbed by the conditions. "It's not as simple as putting a few filters here or there," he says.

Other athletes admit to something that might be called anticipatory survivors' guilt. They know they can parachute into Rio for a few days or a couple of weeks and jet back to cleaner water and attentive doctors. And now that researchers are working furiously to figure out how to contain the mosquito-borne Zika virus linked to birth defects, who's going to gripe about gastrointestinal distress or a skin rash?

OCEAN

NAVIGATOR 4 MARCH 2015 - DRUG RESISTANT BACTERIA FOUND AT RIO OLYMPIC SITE

A

drug-resistant “super bacteria” has been discovered in the waters

where 2016 Rio de Janeiro’s Olympic sailing events are scheduled.

Brazil’s health research institute, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, said it has

discovered bacteria that produce an enzyme that make it resistant to most

forms of treatment in water samples taken from various spots along the

Carioca River. Among the spots is where the river flows into the city’s

Guanabara Bay, site of the 2016 sailing and wind surfing events.

Bacteria with the so-called KPC enzyme are difficult to treat. The

institute said no instances of infection resulting from the contaminated

water have yet been detected but warned of possible danger to swimmers.

According to the institute, even if individuals don’t immediately fall

ill, those who come into contact with the bacteria run the risk of

becoming carriers of the microorganism. Carriers can take these resistant

bacteria back to their own environments and to other people, resulting in

a cycle of infection.

Seventy percent of sewage in this city of 12 million is untreated and

flows, raw, into rivers, onto beaches and into the Guanabara Bay. The

state of water quality has been a major worry leading up to the 2016

summer games. by John

Synder

RIO DE JANEIRO in August 2015, barriers installed across more than a dozen of Rio's dying rivers will hold back garbage that otherwise might drift into the paths of Olympic sailors. A fleet of boats will patrol to keep debris from snagging on a rudder or centerboard and costing someone a medal. Some of the untreated human waste that has long fouled Rio's beaches and docks and picturesque lagoon will be diverted from competitive venues so the athletes who have to navigate them need not worry.

This is what has been promised, anyway. This is the latest stopgap wave of promises made when it was clear the first wave wouldn't be kept.

The solution reminds us of Boyan

Slat's ocean boom system, currently being developed for the Strait of

Japan.

GUANABARA

BAY - In 2015 as part of a greater strategic plan that included designing the eco-barriers that are being constructed across the area's rivers, Projeto Grael helped develop an intelligent model to locate the bands of debris that form in Guanabara Bay, using floats with GPS to map the currents. "The idea was to predict [one day in advance] where the garbage will be tomorrow," Grael says. "The [eco-]boats are very slow. They start working at 8 in the morning. If they have to find the debris stripes, it's about time to stop for lunch."

The valiant little eco-boats are better than nothing, but they're bandages on a gaping wound. Sailors like Brad Funk, a U.S. athlete who competes in the 49er class, have to become proficient at pulling plastic bags and other objects off rudders and centerboards as quickly as possible.

PROPOSED

RIVERVAX™

POLLUTION SOLUTION

One

possible scenario for Guanabara Bay, is to form a business consortium

dedicated to cleaning the watercourse before any more events like the

Olympics are ruined by rampant river pollution and oil spillages that are

damaging fish stocks and causing other environmental havoc.

The

Government might reflect on the potential to levy fines for

oil spillages and the contingency for such events, taking into

consideration the corporate responsibility of oil producers

and the duty of care that the oil producers owe, firstly to their

population - and secondly, to the international community. Another means

to tackle pollution is to educate the citizen with constant reminders

about waste disposal.

While

a fleet of solar and wind powered

robots is waiting

for the inevitable oils spills, they can earn their keep by patrolling the

Bay continuously for plastic and other debris that is coming from the

land.

Such

an endeavor will set a fine example to other nations who, at the moment, are

doing nothing like this.

CHRIST

THE REDEEMER - is an Art Deco statue of Jesus

Christ in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, created by French sculptor Paul

Landowski and built by the Brazilian engineer Heitor da Silva Costa, in

collaboration with the French engineer Albert Caquot. The face was created

by the Romanian artist Gheorghe Leonida. The statue is 30 metres (98 ft)

tall, not including its 8-metre (26 ft) pedestal, and its arms stretch 28

metres (92 ft) wide.

The statue weighs 635 metric tons (625 long, 700 short tons), and is

located at the peak of the 700-metre (2,300 ft) Corcovado mountain in the

Tijuca Forest National Park overlooking the city of Rio. A symbol of

Christianity across the world, the statue has also become a cultural icon

of both Rio de Janeiro and Brazil, and is listed as one of the New Seven

Wonders of the World. It is made of reinforced concrete and soapstone, and

was constructed between 1922 and 1931.

RESTORATION

- In 1990, restoration work was conducted through an agreement among

several organizations, including the Archdiocese of Rio de Janeiro, media

company Rede Globo, oil company Shell do Brasil, environmental regulator

IBAMA, National Institute of Historic and Artistic Heritage, and the city

government of Rio de Janeiro.

More work on the statue and its environs was conducted in 2003 and early

2010. In 2003, a set of escalators, walkways, and elevators were installed

to facilitate access to the platform surrounding the statue. The

four-month restoration in 2010[20] focused on the statue itself. The

statue's internal structure was renovated and its soapstone mosaic

covering was restored by removing a crust of fungi and other

microorganisms and repairing small cracks. The lightning rods located in

the statue’s head and arms were also repaired, and new lighting fixtures

were installed at the foot of the statue.

The restoration involved one hundred people and used more than 60,000

pieces of stone taken from the same quarry as the original statue.[20]

During the unveiling of the restored statue, it was illuminated with

green-and-yellow lighting in support of the Brazil national football team

playing in the 2010 FIFA World Cup.

Maintenance work needs to be conducted periodically due to the strong

winds and erosion to which the statue is exposed, as well as lightning

strikes. The original pale stone is no longer available in sufficient

quantities, and replacement stones are increasingly darker in hue.

ABOUT

GUANABARA BAY

Guanabara

Bay (Portuguese: Baía de Guanabara, IPA: [ɡwanaˈbaɾɐ])

is an oceanic bay located in Southeast Brazil in the state of Rio de

Janeiro. On its western shore lies the city of Rio de Janeiro and Duque de

Caxias, and on its eastern shore the cities of Niterói and São Gonçalo.

Four other municipalities surround the bay's shores. Guanabara Bay is the

second largest bay in area in Brazil (after the All Saints' Bay), at 412

square kilometres (159 sq mi), with a perimeter of 143 kilometres (89 mi).

Guanabara Bay is 31 kilometres (19 mi) long and 28 kilometres (17 mi) wide

at its maximum. Its 1.5 kilometres (0.93 mi) wide mouth is flanked at the

eastern tip by the Pico do Papagaio (Parrot's Peak) and the western tip by

Pão de Açúcar (Sugar Loaf).

The name Guanabara comes from the Tupi language, goanã-pará, from gwa

"bay", plus nã "similar to" and ba'ra

"sea". Traditionally, it is also translated as "the bosom

of sea."

ENVIRONMENTAL

Guanabara Bay's once rich and diversified ecosystem has suffered extensive

damage in recent decades, particularly along its mangrove areas. The bay

has been heavily impacted by urbanization, deforestation, and pollution of

its waters with sewage, garbage, and oil

spills. As of 2014, more than 70% of the sewage from 12 million

inhabitants of Rio de Janeiro now flows into the bay untreated.

There have been three major oil spills in Guanabara Bay. The most recent

was in 2000 when a leaking underwater pipeline released 1,300,000 litres

(340,000 US gal) of oil into the bay, destroying large swaths of the

mangrove ecosystem. Recovery measures are currently being attempted, but

more than a decade after the incident, the mangrove areas have not

returned to life.

One of the world's largest landfills is located at Jardim Gramacho

adjacent to Guanabara Bay. It was closed in 2012 after 34 years of

operation. The landfill attracted attention from environmentalists and it

supported 1700 people scavenging for recyclable materials.

As part of the preparations for the 2016 Rio's Olympics Games, the

government was supposed to improve the conditions, but progress has been

slow and there is fear that most of the improvements will be short-term

which will be abandoned after the Olympics when the little political will

there is for cleaning up the bay disappears.

In June 2014 Dutch windsurfer and former Olympic and world champion Dorian

van Rijsselberghe made an urgent appeal to government and industry in The

Netherlands to collaborate in cleaning up the bay, together with the

Plastic Soup Foundation. The Dutch government picked up the message and

formulated a Clean Urban Delta Initiative Rio de Janeiro together with a

consortium of Dutch industry, knowledge institutes and NGOs which will be

presented to the Brazilian authorities in the State of Rio de Janeiro.

DESCRIPTION

There are more than 130 islands dotting the bay, including:

Lajes

Ilha do Governador – site of Rio de Janeiro's Galeão - Antônio Carlos

Jobim International Airport

Ilha de Paquetá

Ilha das Cobras

Flores

Ilha Fiscal

Ilha da Boa Viagem

Villegaignon

Fundão

The bay is crossed by the Rio-Niterói Bridge (13.29 kilometres (8.26 mi)

long and with a central span 72 metres (236 ft) high) and there is heavy

boat and ship traffic, including regular ferryboat lines. The Port of Rio

de Janeiro, as well as the city's two airports, Galeão - Antônio Carlos

Jobim International Airport (on Governador Island) and Santos Dumont

Airport (on reclaimed land next to downtown Rio), are located on its

shores. The Federal University of Rio de Janeiro main campus is located on

the artificial Fundão Island. A maze of smaller bridges interconnect the

two largest islands, Fundão and Governador, to the mainland.

There is an Environmental Protection Area (APA), which is located mostly

in the municipality of Guapimirim and given the name of (APA) Guapimirim.

CARIOCA

RIVER - One of the polluted rivers that feed into the Bay of

Guanabara.

MULTIHULL

- The Dutch system under development. It is not clear from this picture

how the waste is collected. For sure, the craft will be diesel powered, so

polluting. We are waiting to publish the complete specification if anyone

can point us to that - in the interests of doing justice to the concept.

Any concept is better than no concept.

HISTORY

Guanabara Bay was first encountered by Europeans on January 1, 1502, when

one of the Portuguese explorers Gaspar de Lemos and Gonçalo Coelho

arrived on its shores. According to some historians, the name given by the

exploration team to the bay was originally Ria de Janeiro "January

Sound", then a confusion took place between the word ria, which at

the time was used to designate a bay or a sound, and rio

"river". As a result, the name of the bay was soon fixed as Rio

de Janeiro. Later, the city was named after the bay. Natives of the Tamoio

and Tupiniquim tribes inhabited the shores of the bay.

After the initial arrival of the Portuguese, no significant European

settlements were established until French colonist and soldiers, under the

Huguenot Admiral Nicolas Durand de Villegaignon invaded the region in 1555

to establish the France Antarctique. They stayed briefly on Lajes Island,

then moved to Serigipe Island, near the shore, where they built Fort

Coligny. After they were expelled by Portuguese military expeditions in

1563, the colonial government built fortifications in several points of

Guanabara Bay, rendering it almost impregnable against a naval attack from

the sea. They were the Santa Cruz, São João, Lajes and Villegaignon

forts, forming a fearsome crossfire rectangle of big naval guns. Other

islands were adapted by the Navy to host naval storehouses, hospitals,

drydocks, oil

reservoirs and the National Naval Academy.

FUTURE

OF RIVER CLEANING - A modification of the SeaVax

could cleanse polluted bays without adding to climate

change typical of traditional dredging ships.

This clean-tech could improve social conditions in Brazil manifold, by

targeting river hotspots before the water exits into Guanabara Bay and

then the Atlantic.

RIVERVAX™

TRIALS - Cost effective river pollution monitoring and cleaning all in

one. You have to think big: global. Anything less is a waste of time. It's

pointless trying to clean an ocean with a teaspoon - and you need to cost

any system from collection to disposal or recycling - if that is

practical.

BRAZILIAN

COASTAL ISSUES - Rio's final 2009 bid book included a seven-year commitment to tackling an environmental disaster that took decades to create. The widespread absence of modern sanitation was spun into an asset by the leaders of Rio's campaign. The direct, flattering appeal to the International Olympic Committee was this: Bestow the transformative power of your three-week event on our city. We need the Games more than Chicago does, more than Madrid.

The bid language stated that 80 percent of overall sewage would be collected and treated by 2016, and it pledged the "full regeneration" of the Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon, where rowing and sprint canoe/kayak events will be held.

The same bid document asserted that the Brazilian economy was stable and called funding for Rio 2016 "secure." Six months shy of the opening ceremony, however, recession reigns, inflation rages in double digits and the Games budget has taken a significant hit. Brazil's public health system, already reeling, now must cope with the burgeoning Zika virus epidemic.

Government and organizing committee officials long ago dropped the pretense that the bid's targets for reducing pollution would be met.

"It's not going to happen because there was not enough commitment, funds and energy," Rio 2016 spokesman Mario Andrada told Outside the Lines. "However, we finally got something that the bay has been missing for generations, which is public will for the cleaning.

"Nobody wants to have guests at their house and show a dirty house. So if we're not able to reach the target, we need to keep working until the last minute and make sure that the athletes can compete in safe waters, and we've been doing this."

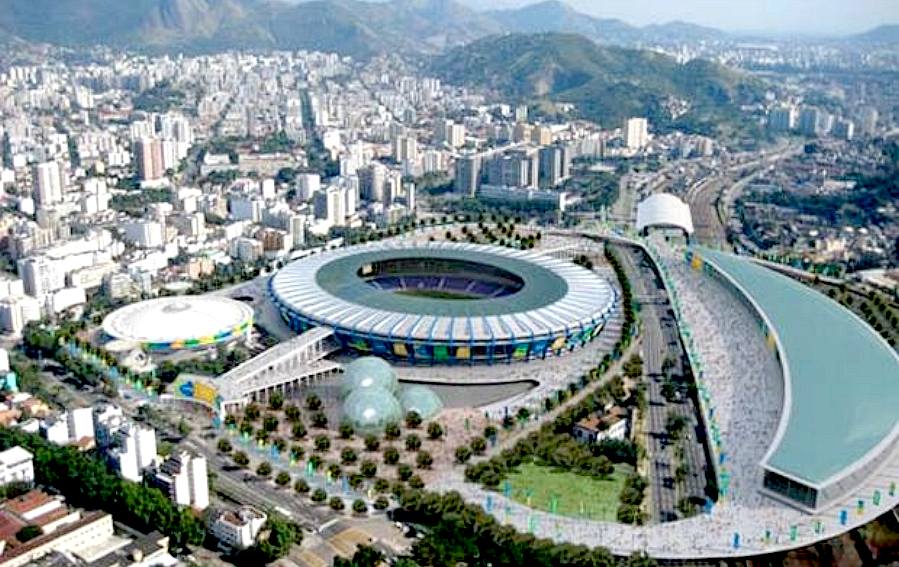

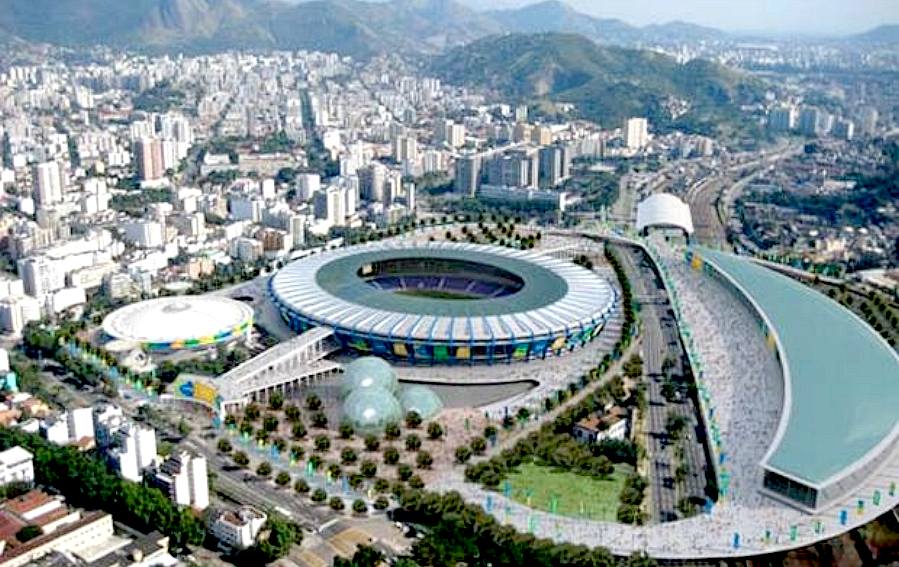

OLYMPIC

STADIUM - Rio de Janeiro's bid for the Summer Games featured an official commitment to cleaner waters. But with less than six months to go, trash and contamination continue to lurk.

The 2016 Summer Olympics (Portuguese: Jogos Olímpicos de Verão de 2016),officially known as the Games of the XXXI Olympiad, and commonly known as Rio 2016, are a major international multi-sport event that will take place in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from August 5 to August 21, 2016. Record numbers of countries and sets of medals are awaiting in the games. More than 10,500 athletes from 206 National Olympic Committees (NOCs), including from Kosovo and South Sudan for the first time, will take part in this sporting event. With 306 sets of medals, the games will feature 28 Olympic sports — including rugby sevens and golf, which were added by the International Olympic Committee in 2009. These sporting events will take place on 33 venues in the host city and additionally on 5 venues in the cities of São Paulo (Brazil's largest city), Belo Horizonte, Salvador, Brasília (Brazil's capital), and Manaus.

The host city of Rio de Janeiro was announced at the 121st IOC Session held in Copenhagen, Denmark, on 2 October 2009. The other finalists were Madrid, Spain; Chicago, United States; and Tokyo, Japan. Rio will become the first South American city to host the Summer Olympics, the second city in Latin America to host the event after Mexico City in 1968, and the first since 2000 in the Southern Hemisphere.

ACIDIFICATION

- ADRIATIC

- ARCTIC

- ATLANTIC - BALTIC

- BERING

- CARIBBEAN - CORAL - EAST

CHINA

ENGLISH CH

-

GOC - GUANABARA

- GULF

GUINEA - GULF

MEXICO

- INDIAN

-

IOC

-

IRC - MEDITERRANEAN -

NORTH SEA - PACIFIC

- PERSIAN GULF

RED

SEA - SEA

JAPAN - STH

CHINA - PLASTIC

- PLANKTON - PLASTIC

OCEANS - SEA

LEVEL RISE - UNCLOS

- UNEP

WOC

- WWF

AMAZON

- BURIGANGA - CITARUM - CONGO - CUYAHOGA

-

GANGES - IRTYSH

- JORDAN - LENA -

MANTANZA-RIACHUELO

MARILAO

- MEKONG - MISSISSIPPI - NIGER - NILE - PARANA - PASIG - SARNO - THAMES

- YANGTZE - YAMUNA - YELLOW

LINKS

& REFERENCE

Wikipedia

Guanabara_Bay The

Guardian sustainable business 2016 February funding problems hit plan clean

Rios polluted waterways olympics

Wikipedia

list_of_oil_spills Ocean

Navigator March April 2015 drug resistant bacteria found off Rio Olympic

site CBS

news

drug resistant bacteria found at rio de janeiro olympics site http://www.rio2016.com/ ESPN

feature

story trash contamination continue pollute Olympic training competition

sites-Rio-de-Janeiro Wikipedia

2016_Summer_Olympics https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2016_Summer_Olympics http://espn.go.com/espn/feature/story/_/id/14791849/trash-contamination-continue-pollute-olympic-training-competition-sites-rio-de-janeiro http://www.rio2016.com/ http://www.cbsnews.com/news/drug-resistant-bacteria-found-at-rio-de-janeiro-olympics-site/

http://www.oceannavigator.com/March-April-2015/Drug-resistant-bacteria-found-off-Rio-Olympic-site/

http://kunststofkringloop.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/CleanCityDeltaRio_eng_web_full.compressed.compressed.pdf

http://www.plasticsoupfoundation.org/

http://www.ihcmerwede.com/

http://www.theguardian.com/profile/oliver-balch

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guanabara_Bay

http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2016/feb/01/funding-problems-hit-plan-clean-rios-polluted-waterways-olympics

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_oil_spills

|